New exhibit reckons with Indiana's racial violence through anti-lynching art

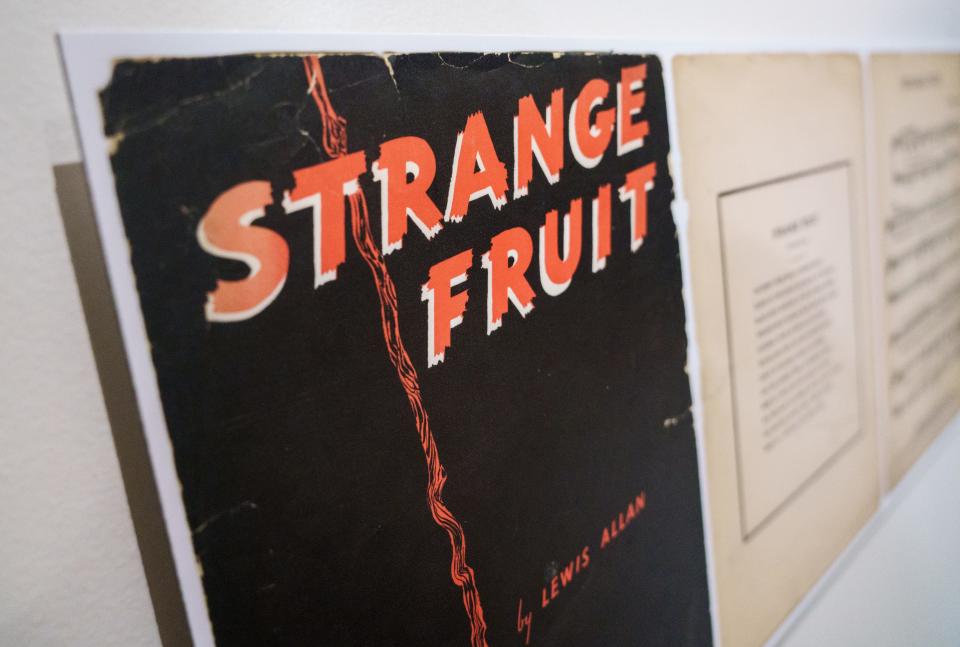

In 1935, the NAACP put on an art exhibition in midtown Manhattan to draw attention to the ongoing terror of lynching and fuel support for federal legislation against it.

Just after it ended, a rival show arrived in Greenwich Village. Artists who supported the Communist Party of the United States of America, seeing capitalism as the barrier to equal rights, called out the NAACP for promoting a bill the leftists found too weak. So they invited art that highlighted labor struggles and racism inherent in the public executions.

Even though they dueled, both shows' visual interpretations aimed to push for collective action. That goal still resonates today with a new exhibition at the Crispus Attucks Museum that pulls artwork and images from its 1935 counterparts.

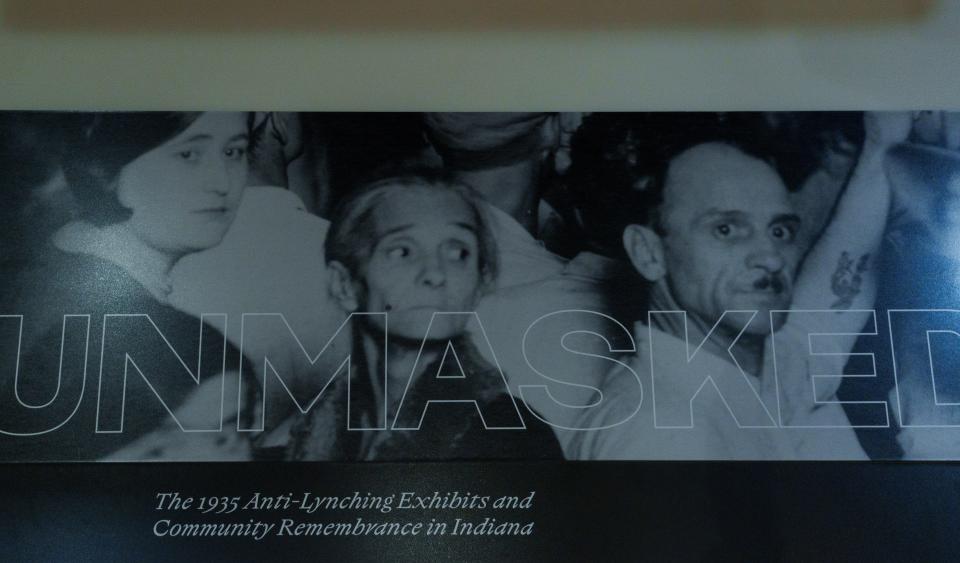

"Unmasked: The 1935 Anti-Lynching Exhibitions and Community Remembrance in Indiana," which runs from Tuesday to March 1 aims to fuel conversations to reckon with racist violence, to honor victims and their families. One way to accomplish that, organizers say, is to build physical memorials in the city. But the next steps will depend on what the community wants.

"By developing an exhibition — and more than an exhibition on lynching, the exhibition on the anti-lynching work that took place — people could be inspired in their own communities to decide whether or not they want to go the route of remembrance and recognition or restoration and repairment," said organizer Rasul Mowatt, a professor at North Carolina State University who's studied lynching and geographies of violence.

How the exhibit started

A lynching is a public killing of a person who hasn't received due process, according to the NAACP. Black people comprised the majority of the victims as their lives were taken in front of white mobs. Criminal accusations, like fabricated rape charges, or upending expected social behavior justified the lynching in the crowd's eyes, the NAACP explains.

"Lynchings weren't just murder but murder to do a job of teaching or pedagogy. So, you kill a person, you display the body to do something," said Mowatt, who formerly taught at Indiana University. "The act of displaying is all about teaching a lesson. The lesson, sometimes it was fear, social control, other things to that nature."

A report by the Equal Justice Initiative counted 18 racial terror lynchings in Indiana between 1877 and 1950. But the violent acts have been tracked to the 1840s, Mowatt said. Even more remain unknown because they weren't necessarily called such when they occurred, he said. Scholars often find them by searching for flogging, beating, burning and drowning.

The history of fighting this violence planted the seed for "Unmasked," which Mowatt put together with Indiana University's Alex Lichtenstein and Associate Professor Phoebe Wolfskill at Indiana University over about seven years.

And while they worked, they saw the growth of Black Lives Matter, the killings of George Floyd and Ahmaud Arbery and the opening of the Equal Justice Initiative's National Memorial for Peace and Justice.

"There suddenly was an efflorescence of memory politics around racist violence," said Lichtenstein, a professor of history and American studies. "That led us to say we need to do more than just historicize these two interesting shows in 1935. We somehow need to connect them to the present."

The art 'Unmasked' shows

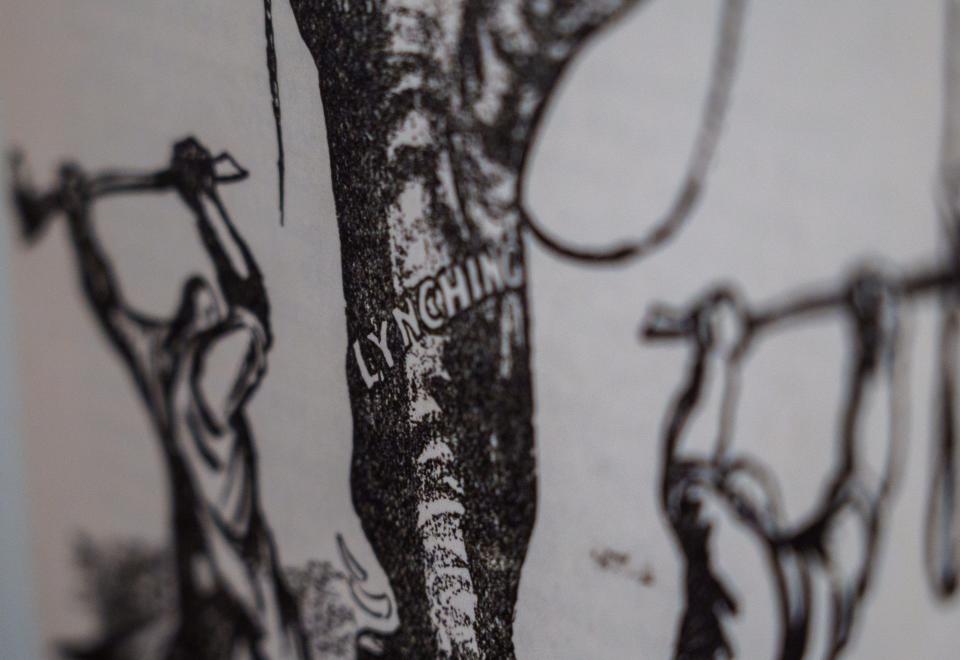

Many of the 50 to 60 artworks in "Unmasked" are digital reproductions or framed works from the 1935 exhibits, Lichtenstein said.

"All those artworks, and many of them are quite horrific to look at ... they're all designed to prompt people to think about and combat this demonic evil," he said.

The artwork addresses the violence without leaning into gore, museum Curator Robert Chester said. A sign notes "Unmasked" is not recommended for children under age 15.

"Exhibits of this nature do a monumental task in telling the story, in sharing the legacy — the trials, the tribulations — and most importantly, the overcoming," Chester said.

Some artworks focus on the families of the victims, like Joseph Hirsch's "Lynch Family," which depicts a woman, with her face buried in one hand and a baby bottle clutched in the other, holding a blanket-wrapped infant who's playing with a rattle.

Other pieces depict the victims, like Hale Woodruff's linocut "Giddap," which shows a menacing group preparing to hang a man who's bound in the back of a wagon. The Hoosier artist, who was working in Atlanta at the time, created another in the series that shows a man's body on the steps of a church. A 2021 piece by Ken Gonzales-Day takes Woodruff's work one step further by removing the victim from the scene to reflect on the physical space.

Among the most chilling works are those that focus on the mobs. In Reginald Marsh's drawing "This is Her First Lynching," a woman casually chats with the person next to her as she holds up a little girl who's touching her finger to her chin. Around them, people crowd in for a better view.

Also on display is the 1930 Marion lynching photo and art that comments on it. The mob members staring directly at the camera prompt Indianapolis-based historian Leon Bates to question why more public acknowledgement doesn't exist today. Last year, a federal bill that criminalizes lynching passed after more than a century of efforts.

"There's no one shying away from the camera, so if you didn't shy away from it when you did it — and we're talking almost 100 years ago in this case — why do we not want to talk about it now?" said Bates, whose research includes the urban environment's intersection with race, policing and violence.

Where conversations can go from here

Among organizers' main goals for "Unmasked" are conversations. The exhibit began its journey in Bloomington earlier this year, and after Indianapolis, plans are for it to travel around the state. Information on related guided tours, workshops and events will be forthcoming.

"Unmasked" also prompts conversation on how to acknowledge the past, honor victims and organize against anti-Black violence today. The exhibit shows how other communities around the state like Posey County and Terre Haute have put up memorials.

As Indianapolis decides how it might move forward with memorials, residents have already been working to honor lynching victims. Bates submitted extensive research for a coming downtown marker for John Tucker, a farmer, father and husband who was killed in an 1845 lynching near Illinois and Washington streets.

The Indiana Remembrance Coalition last year helped uncover the story of George Tompkins, whose death certificate was corrected from suicide to homicide 100 years after he was killed in Riverside Park and who now has a headstone at Floral Park Cemetery.

"Starting out with the markers that explain these things, it makes it much harder to keep kind of pushing (the history) into the closet," Bates said.

Other actions communities can take today include sharing a sense of victims' lives instead of just their deaths; correcting the record; and asking the city, county and state to take responsibility for cases in which law enforcement failed, Mowatt said.

Ultimately, "Unmasked's" power for today lies in collective action, which people found in the 1935 exhibits, he said.

The exhibit is "not about the horrors of lynching. It's about the actual fight against the horrors of lynching," he said. "And if these people could do what they did in the past, why can't we?"

If you go

What: "Unmasked: The 1935 Anti-Lynching Exhibitions and Community Remembrance in Indiana"

When: Tuesday-March 1. 10 a.m.-6 p.m. Tuesday-Friday. 10am-3pm Saturday-Sunday. Visitors can walk in but organizers strongly encourage them to make reservations by calling or texting 317-409-5281.

Where: Crispus Attucks Museum, 1140 Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. St.

Cost: $9

More information: unmasked.myportfolio.com

Looking for things to do? Our newsletter has the best concerts, art, shows and more — and the stories behind them

Contact IndyStar reporter Domenica Bongiovanni at 317-444-7339 or d.bongiovanni@indystar.com. Follow her on Facebook, Instagram or Twitter: @domenicareports.

This article originally appeared on Indianapolis Star: Exhibit of anti-lynching art reckons with Indiana's racial violence