Exclusive: With more immigrant children in detention, HHS cuts funds for other programs — like cancer research

The Department of Health and Human Services is diverting millions of dollars in funding from a number of programs, including the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the National Institutes of Health, to pay for housing for the growing population of detained immigrant children.

In a letter sent to Sen. Patty Murray, D.-Wash., and obtained by Yahoo News, HHS Secretary Alex Azar outlined his plan to reallocate up to $266 million in funding for the current fiscal year, which ends on Sept. 30, to the Unaccompanied Alien Children (UAC) program in the Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR).

Nearly $80 million of that money will come from other refugee support programs within ORR, which have seen their needs significantly diminished as the Trump administration makes drastic cuts to the annual refugee numbers. The rest is being taken from other programs, including $16.7 million from Head Start, $5.7 million from the Ryan White HIV/AIDS program and $13.3 million from the National Cancer Institute. Money is also being diverted from programs dedicated to mental and maternal health, women’s shelters and substance abuse.

According to data from the Office of Refugee Resettlement obtained by Yahoo News, there were 13,312 immigrant children in federal custody as of Wednesday, Sept. 19, with ORR’s existing facilities at 92 percent capacity.

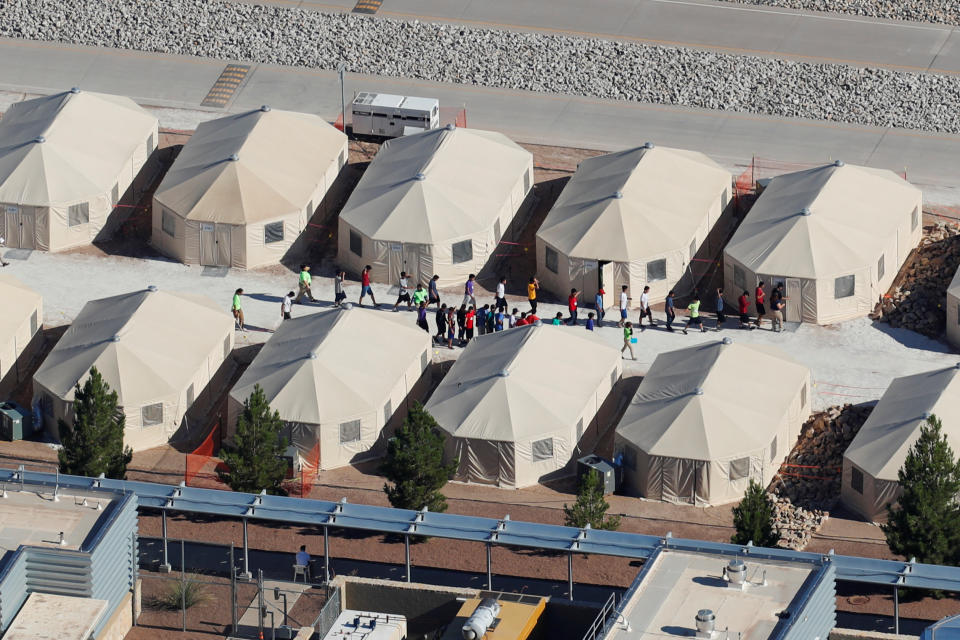

The latest figures demonstrate the continued growth of this population just one week after the New York Times reported that the number of detained immigrant children in the U.S. has soared to record highs over the last year, from 2,400 children in May of 2017 to 12,800 earlier this month. Last week, HHS confirmed its plan to extend use of an emergency shelter in Tornillo, Texas, for the third time since it opened in June, and expand capacity at the “tent city” from 400 to 3,800 beds. The estimated cost of operating such emergency facilities is $750 per child per day — approximately three times the cost of a regular ORR shelter.

“We support making sure ORR gets all the resources they need to help kids,” said Sen. Chris Van Hollen, D-Md., a member of the Senate Appropriations Committee and one of 19 Democratic senators who wrote Azar in July expressing concern over “a troubling pattern of chaotic, ideologically driven and opaque policymaking” in ORR’s unaccompanied child program.

Van Hollen told Yahoo News Wednesday that the notification of the reallocation of funds to the Unaccompanied Alien Children program leaves key questions unanswered.

Van Hollen said he was questioning “the reasons for need for additional money and how much of it is because you have more UACs coming across the border and how much is due to the Trump administration’s family separation policy?” He urged the Senate Subcommittee on Appropriations for Labor, Health and Human Services, Education and Related Agencies call Azar and other administration officials to a hearing on how the money would be used in the UAC program, and the impacts on the programs being cut.

“The American public is entitled to facts behind the policies here,” he said.

This is hardly the first time HHS has had to move money around to accommodate an influx of unaccompanied immigrant children in its care. But although the number of unaccompanied immigrant children apprehended along the border U.S. in fiscal year 2018 is on track to surpass that of the previous year, the rate is still well below those seen in 2014, when the flow of unaccompanied children across the border reached crisis-level proportions, or during the subsequent peak in 2016. And while the family separation policy has contributed to the demand for additional beds, the main reason is that children are spending more time in custody before they are released to a sponsor or returned home.

So far this month, discharges from custody have been running at a rate of around 0.6 to 0.7 percent per day, less than half the 1.5 percent shown in reports obtained by Yahoo News from early April and from late July. Meanwhile the intake of unaccompanied immigrant children into ORR facilities has remained relatively steady, with average daily referrals from Customs and Border Protection in the range of 100 to 200.

“This is not a story about a historically large surge in arrivals,” said Mark Greenberg, a former official with HHS’s Administration for Children and Families. “The story is fundamentally about a significant slowdown in children being released from care.”

Greenberg, now a senior fellow at the Migration Policy Institute, worked at the Administration for Children and Families (ACF), which includes ORR, from 2009 to 2017, serving as acting assistant secretary during the last three years of the Obama administration. He said that even during the major surges of 2014 and 2016, the goal was to keep the average daily discharge rate at 3 percent. “Most typically, the discharge rate was somewhere in the 2s, with significant concern if it fell below 2,” he said. “It was certainly not below 1.”

In his letter notifying Sen. Murray of the transfer of funds, Azar stated that, based on the current growth pattern and what he described as “an increased length of time needed to safely release unaccompanied alien children to sponsors, HHS is preparing for the trend of high capacity to continue.”

The majority of children housed in such facilities come to the U.S. on their own from the northern triangle countries of Central America — Guatemala, El Salvador and Honduras — often fleeing gang violence. However, during the months that border officials were separating families under the Trump administration’s zero-tolerance policy, children who’d actually entered the country with a parent were being reclassified as “unaccompanied” and referred to ORR, in a chaotic process that left children stranded, in some cases while their parents were being deported. The subsequent effort to reunite those children, which has required the diversion of staff from ORR and elsewhere throughout the Administration for Children and Families, has likely contributed to the slowdown in discharges.

But that’s not the only reason. Months before the family separation crisis came to a head, unaccompanied minors were already spending extended periods of time in ORR facilities, which are intended to house children temporarily until a parent or suitable adult sponsor can be identified.

In March, Yahoo News reported that a new policy requiring ORR Director Scott Lloyd to personally approve the release of certain children resulted in many remaining in custody longer, even after a proper sponsor had been approved. Lawyers representing the children and immigration advocates said they were being falsely suspected of gang affiliations. More and more aged out of custody and were transferred to adult detention facilities on their 18th birthdays. In response to a lawsuit by the New York Civil Liberties Union, a New York federal judge in June determined that Lloyd had violated the federal Administrative Procedure Act by enacting the policy almost immediately upon being sworn in as director, “with no record demonstrating the need for change,” and ordered him to halt it.

At the same time, parents and other potential adult sponsors who might have taken the children in were being frightened away by the environment of heightened enforcement under Trump. More than 400 people were arrested by ICE last summer in an operation targeting parents of unaccompanied immigrant kids. A rumor spread about an agreement among ORR, ICE and CBP that would require ORR to inform ICE with the names, fingerprints and other personal details of not only proposed sponsors but all adults in the household. Even before the policy was implemented in June, the prospect was deterring potential sponsors from coming forward.

“As soon as the announcement was made that they were going to do this, it had an immediate chilling effect,” said Jennifer Podkul, policy director at Kids in Need of Defense (KIND), which provides pro bono legal services to immigrant children.

“We started seeing kids linger in care longer before it officially went into effect,” said Podkul, noting that KIND also received calls from the Honduran Embassy asking whether it should advise Honduran citizens in the U.S. against coming forward to sponsor a child.

Matthew Albence, the executive associate director for enforcement and removal operations at ICE, validated these fears during a hearing about family detention before the Senate Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs Committee on Tuesday, stating that under the policy ICE has apprehended 41 prospective sponsors so far.

Greenberg explained that the process of releasing unaccompanied minors into the care of adult sponsors has always involved a bit of a balancing act.

“There are lots of tradeoffs and judgments involved in that process,” he said. “On the one hand, [it’s] important to be sure that children are being released in safe and appropriate settings. On the other hand, there’s a strong interest in children being released to the least restrictive environment quickly, so long as it is safe to do.”

Greenberg said the agency was prompted to review and strengthen its vetting policies after a number of teenagers who’d come in the surge of 2014 were mistakenly released to traffickers in Ohio who claimed to be family friends. After that, he said, the agency expanded home studies and background checks for all prospective sponsors as well as backup care providers, checking for histories of child abuse and neglect.

Greenberg said that during his time at ORR, routine fingerprinting for parents seeking to regain custody of their children was not required, since ORR “very rarely received any information from fingerprinting that they didn’t otherwise get from public records checks for criminal history.” And it was “clear that fingerprinting was a significant deterrent for parents coming forward.”

“The more you create a situation where children are more likely to go to distant relatives or nonrelatives, the more dangerous it is for children,” said Abigail Trillin, a staff attorney at the San Francisco-based Legal Services for Children. “We’re starting to see undocumented folks not going to come forward, therefore children either stay in detention or go to more distant people who might happen to be documented,” she said, a “situation that is at best challenging and at worst dangerous for children.”

_____

Read more from Yahoo News: