EW's Origin Story: How the magazine's evolved since its 1990 launch

“Let me tell you why you’re doomed.”

It was 1989, three months before the launch of Entertainment Weekly, and three days after I had started working here as a staff writer. The man who buttonholed me in the elevator was a longtime magazine editor — an expert in the field. He seemed oblivious to my discomfort, and also to his own, since he continued to hammer home his point while the elevator door banged insistently against his hip.

“You’re doomed,” he said, “because nobody cares. People like movies. People like TV. But they don’t want to know how it’s made. They don’t want to talk about it. They don’t want to read about it. And they don’t want to think about it. I give you six months.”

He was not alone. “Doomed” was an early EW prognosis, one that some members of the magazine’s original staff cheerfully co-opted by starting an office pool about how many issues we would last. (The highest you could bet was 26.) I will admit to a small twinge of satisfaction each time a publication that smugly predicted our quick demise was suddenly confronted with its own. But at the end of our first quarter century, I feel much deeper satisfaction in knowing this: He was wrong. You did care. You still do.

Twenty-five years ago, however, the mistake was understandable. The world into which Entertainment Weekly was born was one in which there were three networks (at first, the magazine’s TV department wasn’t sure whether to count Fox as one because its ratings were so low — and then The Simpsons arrived). There were a handful of basic-cable options, no such thing as DVDs, an indie-film movement that had just barely begun, no MP3s, no streaming, no file sharing, no recaps, no Oscar season that received months of media attention, no binge-watching, no live-tweeting, no websites that mattered, no Internet to speak of, and thus, when it came to popular culture, no sustained discussion. Was that a void waiting to be filled, or just the natural state of things? At the magazine, we knew we were obsessed, but how many of you were?

RELATED: EW’s 25 Best Movies in 25 Years

News arrived agonizingly slowly; we kept CNN on all day at a low background hum in case anything happened. Press releases and reader letters came via snail mail. There was an early internal debate about whether the magazine should get this thing called a fax machine. Would anybody use it? Would anybody need anything that fast? “Buzz” about a new movie or album or TV series or book or star was not quantifiable in anything approaching real time. So a gigantic unanswerable question hung in the air: Were we having a conversation about pop culture, or were we just talking to ourselves?

In the early years of EW, we had no choice but to follow our passions, our personal tastes, and our instincts—and to hope that in doing so, we would reach an audience of the like-minded. Sometimes we played what turned out to be a pretty good long game: The subject of the magazine’s first cover was k.d. lang. (At EW’s launch party, Regis Philbin looked at a blowup of the cover photo and said, loudly, “Who’s he?”) While the magazine’s first (and only) public slogan was “Kick back. Chill out. Hang loose. Have fun” (no apologies — it was 1990), privately, our mission was defined differently: In any spare time we had after explaining to people that, no, we were not affiliated with Entertainment Tonight, we were charged with reporting on the big, the hyped, the important, and the good. At least one of those boxes had to be checked to merit serious attention in the magazine.

RELATED: EW’s former editors share their favorite and least favorite covers over the years

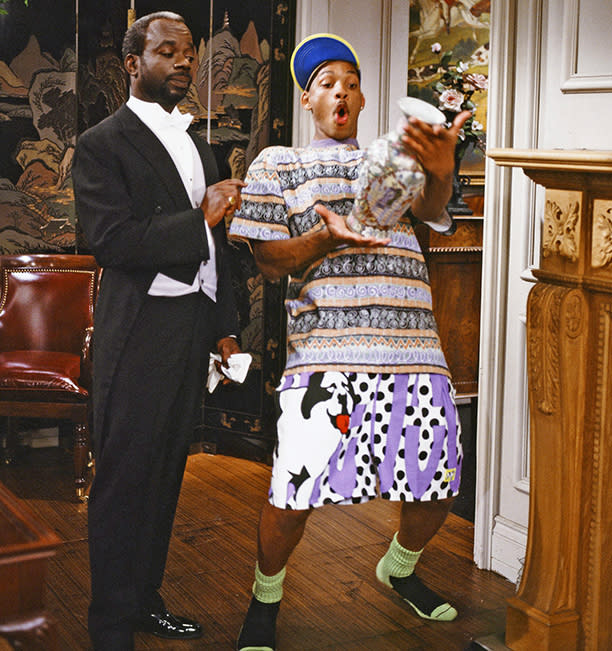

As a result, every story we did felt like a kind of bet: Was the brand-new thing we were covering going to be embedded in the culture a quarter century later? Sometimes it was! My very first assignment was to go cover the launch press conference of the channel that became Comedy Central, and soon after, I got to write about a new sitcom star, Will Smith, and a fledgling TV series that had just gotten through a somewhat rocky first season, Law & Order. But sometimes, we knew the stuff we were reporting on — the thing that everyone was talking about that week — would probably wind up as a trivia question, a delightful time capsule of a fleeting moment in pop culture (Wayne’s World, Vanilla Ice, Hammer time!). Sometimes we literally didn’t know what to cover: We would bang our heads against the wall only to discover they were empty. (One brainstorming session ended not with a “Eureka!” but with one exhausted staffer raising his hand and saying, “I’ve noticed that children are getting larger, but children’s dogs are getting smaller.”)

RELATED: 25 things we can’t believe about 1990

And, sadly, there were also countless man-hours expended on instant fizzles unworthy of even a week’s attention. (Had I known the Internet would come into existence and make everything searchable forever, I might have waxed just a shade less enthusiastic about how Cop Rock was going to change television.) On the other hand, we weren’t — and aren’t — trying to be timeless. Entertainment has always been a combination of the enduring and the ephemeral, and part of the fun of covering it is complete uncertainty about what posterity will decide.

[pagebreak]

In those early years, we learned to listen to ourselves (and each other), mostly because there was so little outside noise. If, one morning, the editorial meeting couldn’t get started on time because half the staff was sifting through every detail of the previous night’s episode of Twin Peaks, that probably meant something. (Incidentally, 25 years later, we’re still going over every detail of Twin Peaks, limbering up for 2016.) And we learned to listen to readers, who, long before the instant gratification of comment boards, wrote in and told us what they cared about. Two of the mainstays of EW coverage in the magazine’s first decade were Seinfeld and The X-Files, the subjects of intensely detailed episode guides, a format the magazine largely invented. Was everyone talking about ER? Kurt Cobain? Batman? The Spice Girls? Melrose Place? Harry Potter? Friends? We covered them — ad nauseam and sometimes beyond. Were people obsessed with particular stars? We followed them from project to project. Closely. To this day, I think Julia Roberts may be embarrassed about how many times we put her on the cover. When you groaned “Not again!” about certain subjects, chances are that some of us were groaning too. But in editorial-meeting battles, people who were not sick of something almost always outshouted those who were. Passion almost always trumps indifference.

RELATED: 25 Best TV Characters in the Past 25 Years

It seems hard to imagine, now, in a manifestly opinion-driven culture, how often our critics, a mainstay of the magazine from the first issue, came under fire for daring to have minds of their own. When the magazine panned Pretty Woman, our critic Owen Gleiberman, and those who supported him, were lambasted for being out-of-touch elitist anti-populist smug joyless big-city jerks. (Twenty-five years later, our critics get the same complaints, but faster.) There were, and still are, plenty of people who think the job of a critic is to be nothing more than a human thermometer, carefully recording and accurately reflecting the temperature of the public. In the early days of EW, it was a battle to convince some people — editorial higher-ups outside of the magazine and studio and network publicity machines, among them — that our critics could think and say pretty much whatever the hell they wanted, and that they operated independently of the rest of the magazine’s editorial coverage. Readers didn’t need convincing. They loved our critics, they hated our critics, they loved to hate our critics. They invented whole personalities for them. They called them (and called them out) by their first names. They engaged in fluctuating weekly tussles with them. The ongoing conversation had begun.

Twenty or 25 years ago, a lot of that discussion was about what was mainstream and what was fringe, what was good for a general-interest publication and what was simply a staff obsession. But the mainstream was permeable, and redefining itself every day. I was at a shoot for Vanessa Williams in 1992 when a stylist looked at her and said, approvingly, “You betta work, bitch!” Williams looked at him and said, “What did you say?” “Honey,” said the stylist, “haven’t you heard of RuPaul?” He ran off to play “Supermodel” for her. She was delighted. Suddenly, maybe it was okay to cover a 6-foot-4-inch-tall drag superstar in the making.

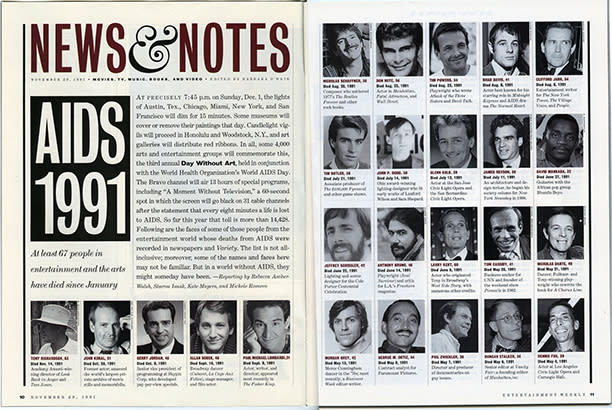

EW was born at the early height of the AIDS crisis, and the epidemic changed and reshaped our mission in those first years. Covering the entertainment industry meant tallying loss — by the month, and sometimes by the week, as colleagues and friends, public figures and behind-the-scenes artists and craftsmen, died at a terrifying rate. In 1991, in conjunction with World AIDS Day, we published our first Faces of AIDS section, a yearbook of tragedy featuring pictures and names of 67 artists who had died of the disease in the past year. It became an annual feature, engulfing more pages as the death toll mounted. By the 1994 issue, there were 137 faces. The following year, the numbers started to drop — first slowly, then rapidly. In 1995, EW became the first mainstream magazine to publish an issue devoted entirely to the ways in which LGBT material, performers, characters, and themes were having a breakthrough moment in pop culture. The issue, by its very existence, took a stand in favor of acceptance, diversity, and inclusion. There have been times when we have told that story well, and other times and ways in which we have fallen short. But making it part of our mission — with the encouragement of readers who told us it mattered to them — made EW aim higher, and reminded us that covering entertainment with playfulness, joy, and intelligence also meant taking it seriously.

Meanwhile, you wanted more. More of everything. More reviews, bigger features, longer charts with more statistics, more news. If we left a single certain-to-be-obscure movie out of a preview issue, you wanted to know why. If we made a list — and good lord, did we ever love to make lists! — your letters would begin “How could you possibly leave out…” It sometimes felt as if you were coediting the magazine with us, since many of our office conversations began that way too. As tabloid entertainment journalism became a phenomenon, if we stepped too far in the direction of gossip or tawdriness, you’d slap us back into line. “That’s not what I come here for,” you’d tell us. We listened.

[pagebreak]

And then, the Internet changed everything. That’s a sentence you could probably find in any cultural history covering the past 25 years, and there’s no point in recapping the joys (Faster! More mutual! More interactive! More communicative! Faster still!) and the hazards (Dumber! Meaner! Noisier! More bullying! TOO fast!) that it brought and continues to bring to much of journalism. At first, we weren’t sure what to do with it, so we did the only thing we were certain we knew how to do: We reviewed it. For a while, “Internet” became a review section, nestled uncomfortably alongside Movies, Music, TV, and Books, and curated by the first people on our staff who were smart enough to see further ahead than the rest of us could.

WANT MORE EW? Subscribe now to keep up with the latest in movies, television, music, and more.

Eventually, it became the minnow that ate the whale. The theoretical conversation we’d been having with you in our heads for years became an actual one. We had always conceived of EW as a kind of big, friendly club with a really easy door policy: You just had to care about some of the stuff we cared about enough to want to talk about it. Now, finally, with EW.com, we were talking. We could follow TV shows week by week, with analyses that could arrive the next morning rather than the next week. From Survivor to Lost to Breaking Bad, we could go into a kind of depth and detail and specificity just this side of madness, and to our surprise, you were not only along for the ride, but you encouraged us to go deeper. If we couldn’t stop thinking about a song or a movie or a scene or a shot or an idea, we had the instant gratification of exploring it. We could respond to news in the moment — and, like everyone else in journalism, we had some lessons to learn about the perils of in-the-moment responses. And even as that all happened, we faced a new version of the challenge we had always faced — to deliver, every week, a print magazine that you’d be happy to find in your mailbox.

Back issues of magazines are always, eventually, quaint. They take explaining: Yes, kids, once upon a time, a group of otherwise sane adults thought that a prime-time soap called Models Inc. was cover-worthy, and that everybody would want to go see a movie called Waterworld. Sometimes they take no explaining at all if you were there, and if you weren’t they offer a great history lesson in miniature: Here, in 1991, was the moment that Thelma & Louise opened. Here’s the first mention of The Silence of the Lambs. This is what the magazine looked like, and what pop culture felt like, the week Kurt Cobain died. This is the way the editorial staff, which was and is primarily based in New York City, struggled to respond to 9/11, an event after which we wondered if we should publish at all. This, through the prism of entertainment, is who we were, for the past 25 years. EW has grown up, and now, some of you have grown up with it. Taking the journey together has been our privilege.