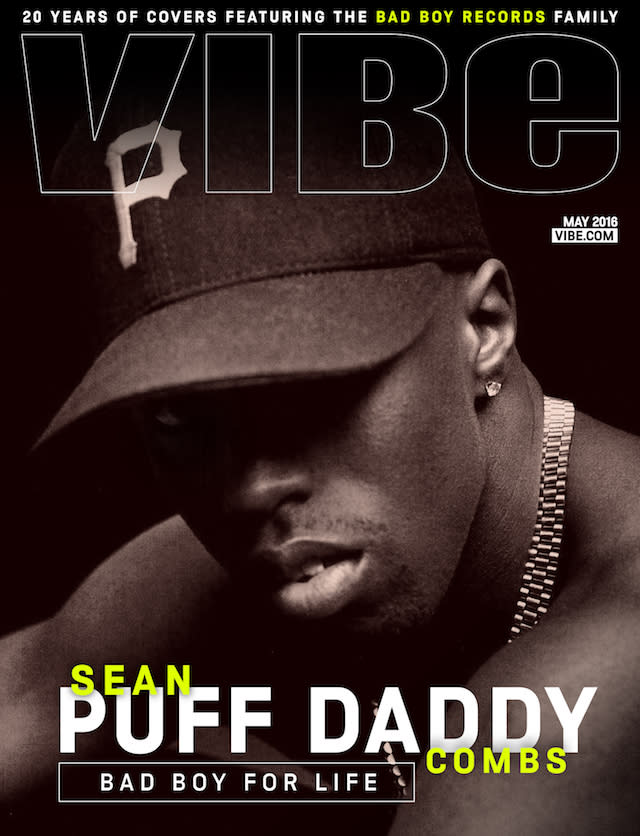

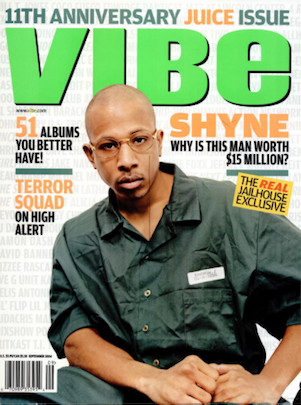

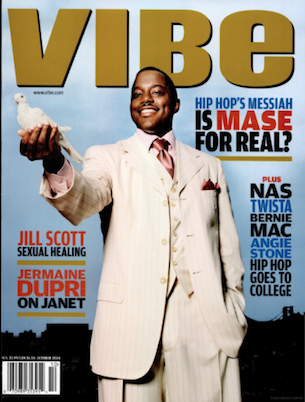

The Evolution Of Sean “Puff Daddy” Combs And The Bad Boy Family Through VIBE’s Covers

The launch of VIBE was the definitive introduction of the power of Hip-Hop and culture to move the crowd. Before the Internet, before email, before social media…there was VIBE. The magazine founded by the legendary musician/producer Quincy Jones, was created on the pulse of our music, as it was riding the power of television, radio, film and fashion becoming charged with the electricity of the streets. Thus, VIBE provided the all encompassing platform to showcase the evolving genre while it solidified a firm placement in the fabric of this nation. This new culture gave rise to stars, and none shone brighter than Sean “Puff Daddy” Combs. It was July of 1993, while we were moving into our new VIBE offices on Lexington Avenue in Manhattan, we faced the excitement, the energy and the fear of which articles to include in our forthcoming September 1993 debut issue. The cover was easy since we were all sitting there listening to The Chronic by Dr. Dre and completely entranced by the Long Beach, California repping, sing-song delivery of Snoop Doggy Dogg, but prioritizing the contents….that would be much harder.

Scott Poulson-Bryant (Dr. Bryant now), a brilliant writer who also gave VIBE its name, spoke lucidly and clearly about an A&R Executive who was setting the entire music game on fire working at Andre Harrell’s Uptown Records. He had been working diligently on a story about Sean Combs and his groundbreaking work with Mary J. Bilge, Jodeci, Heavy D and other acts on the powerhouse label. All was good, we were hot, and the young genius known as Puff Daddy was in our first issue.

Then a confluence of tragedy and internal management struggles with the mogul Harrell led to Combs’ ouster from Uptown Records. And this led to our FIRST serious editorial decision of our young magazine’s career–”Do we keep Puffy in this issue or do we wait and see what happens with him and put him in a later issue?”

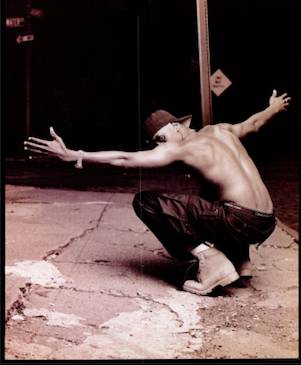

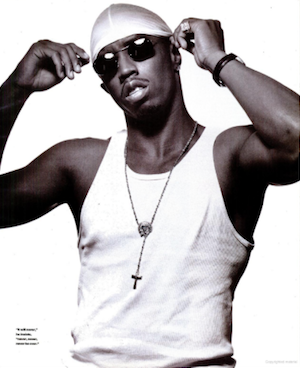

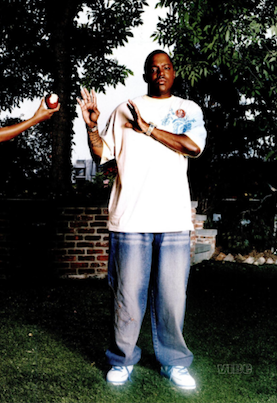

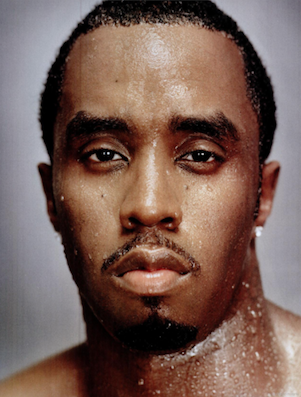

Photo By: Butch Belair

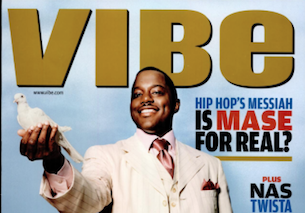

To our credit, we continued with the piece in the inaugural issue, showing Puff in his brash, bossy and shirtless glory. He soon secured a lucrative label deal with Clive Davis’ Arista Records for his own Bad Boy Records. The future for the young entrepreneur was bright, but not sparkly, as he has constantly been met with drama and severe loss during his journey. With unimaginable highs, like the platinum success of artists like Brooklyn’s The Notorious B.I.G., R&B trio Total and introducing the masses to Harlem World’s Ma$e, Combs would face the unfortunate battle of coasts with Death Row Records, the soul crushing death of The Notorious B.I.G and himself looking at serious jail time at one point.

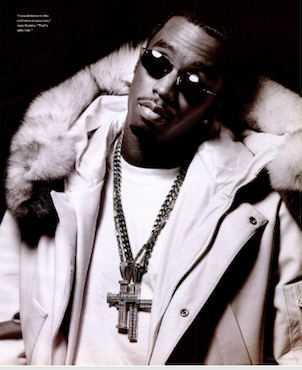

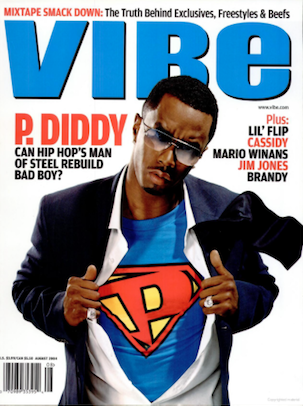

Yet, surviving the times is what Combs does best. Not only surviving but thriving in an entertainment world that hunts you down to throw you out, he’s prospered in areas previously closed to young black executives. Defining eras from the early 90s to now, he’s stumbled and rebounded with stints in acting on Broadway and entering Hollywood’s silver screens to snatching prestigious awards in the fashion world with his Sean John clothing line. From philanthropy to politics to purified water companies, Combs has done it all…the man even ran the New York City marathon, hence the moniker “Diddy Runs The City.”

The path to over 20 years of Bad Boy Records has found Combs breaking the rules and making his own, and VIBE has been there for the whole ride. He’s been featured on six covers and a few non-Bad Boy covers, while his artists went on to rock another nine.

Puff took a pass that was played by Quincy and Def Jam Records founder Russell Simmons, and added a whole new direction to infuse the culture. He constantly expanded the limits of industry and commerce while innovating aggressively and creating a history making enterprise fueled by the sound and hard work that was put forth by the countless moguls he helped create and longtime partner in building Bad Boy Records, Vice President Harve Pierre.

Aside from breaking the glass ceiling of mass communication and founding a cable network in REVOLT TV, Combs is now on the brink of kicking off the Bad Boy Family Reunion Tour, bringing together the acts that he introduced to the world like The Lox, Ma$e, 112, Carl Thomas, Faith and many more… He said it from the beginning, “I thought I told you that we won’t stop.”

Damn straight.

Congratulations to Harve Pierre, the founder of REVOLT Sean “Puff Daddy” Combs, and the entire Bad Boy Family. #badboy4life – Keith Clinkscales [Founding CEO of Vibe Magazine and is currently the CEO of REVOLT, the music and culture channel founded by Sean “P Diddy” Combs]

Read the Post

Puff Daddy: This Is Not A Puff Piece

The Evolution Of Sean “Puff Daddy” Combs And The Bad Boy Family Through VIBE’s Covers

Puff Daddy: This Is Not A Puff Piece

Written By: Scott Poulson-Bryant

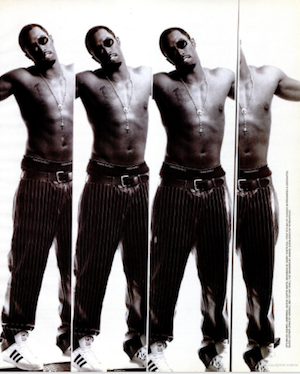

Photographs By: Butch Belair

Issue: September 1993

PROLOGUE: Before Andre Harrell fired Puff Daddy, there was another story. Before he walked into Puffy’s office on that nasty hot evening on July 8 and told his protégé that there was room for only one king at the castle called Uptown Entertainment; before Andre Harrell told Puffy that he would have to take his new record label, Bad Boy Entertainment, elsewhere; before Puffy packed up his office; before the telephone lines burned with theories )Andre’s threatened by Puffy’s success. Andre was pressured from higher-ups at MCA, Andre’s bosses never like Puffy anyway, they never understand him, never tried to, Puffy’s just a troublemaker); before Andre was saying that Puffy “had particular ways he wanted to do things that weren’t in the direction I wanted Uptown to go…” Before all that, before Andre decided that Puff Daddy was “unnecessarily rebellious,” there was another story to be told about Puff Daddy. A story that started like this…

AS hip hop makers its mad dash toward the finishing line of high capitalism, it will need a hero. And there he is, shirtless, the waistband of his Calvin Klein boxer briefs peeking perilously over the edge of his black shorts, the skull tattoo on his left breast gleaming red, mingling with the other guests at Uptown Entertainment president Andre Harrell’s party in a posh suburb in northern New Jersey. It is summer 1992 and it’s the weekend that Whitney married Bobby and the cream of black entertainment society has invaded this coast for the show. The FOAs (Friends of Andre) swim in the pool, jam to Kid Capri on the 1 and 2’s, and play shirts-on-skins b-ball on the court out front, waiting for the catered food to arrive from the Shark Bar, Manhattan’s West Side eatery of choice for black entertainment types. Russell Simmons is there, and Veronica Webb and Keenan Ivory Wayans and Babyface. But Puff Daddy is the only one with a briefcase, one of those shiny, bomb-protectant joints, opening it and closing it periodically to show folks the information inside: initial artwork for the logo of Bad Boy Entertainment. And his first words to me, as I make my way onto the back porch, are not hello or even hi how are you, but, instead, “Yo, nigga, why you frontin’?” Frontin’, as in not calling him when I said I would.

We’d actually met a few weeks earlier at a fashion show, and after introductions and small talk, he’s said to me then, “You should write a piece about me.” Not only, I thought, is he an A&R man, party promoter, stylist, video director, record producer, and remixer, but he’s also his own publicist. It’s that kind of boldness, that confident sense of purpose, that drives Sean “Puff Daddy” Combs along the path to success he has chosen. Indeed, he is a boy wonder, and, at 22 years old, possibly the second-youngest record-company president — just two months behind Dallas Austin – when Bad Boy launches this year. Codirecting and costarring in the videos of Mary J. Blige and Jodeci – the jewels in his young crown achievement – he inspires the same kind of awe and jealousy usually reserved for a front-and-center star. There is so much to do, in fact, that he employs two live-in assistants to manage his growing schedule of meetings and growing roster of acts.

And Puffy cherishes his status, thrives on the exuberance of his youth and its possibilities. He likes the hanging-out nature of his work – the club-going and party-hopping, keeping on the very edge of what’s young and black and hip. But Puffy brings something else to his behind-the-scenes machinations – he’s his own best logo. The postcards announcing the debut of Bad Boy feature Puffy in all his cultivated B-boy glory, shirtless and seated underneath a lonely streetlamp in one, poised behind jail-like bars, his arms raised dramatically, in another. He has the aura of a performer; quite possibly he is the only A&R executive in the business with as many groupies as his artists. He’s the shadowed love man in Mary J. Blige’s “Reminisce” video and the placard-carrying strutter in Heavy D’s “Don’t Cures” clip. “Puffy,” says Andre Harrell, “is the perfect icon. He embodies that kind of charisma and star power.” In the fickle world of hip hop, Puffy creates heroes and makes a hero of himself in the process.

But heroes, because they are heroes, usually bear the cross of their constituents’ sins; heroes often take falls. And just after Christmas1991, as he attempted to present a gift to his community in the form of a fund-raising celebrity basketball game, Puff Daddy’s ascendency almost came to its first abrupt and complete – some say inevitable – stop. What began as “an opportunity to get dressed up in your newest gear, a colorful event ‘cause black folks always want something to go to to be colorful,” as Andre Harrell put it, ended up as a tragedy that would reverberate around the globe. At the Nat Holman Gym at City College in Harlem, nine people were killed, victims of a stampeded of bumrushing, overeager fans. Puffy was the promoter and organizer, and in the aftermath of the event, he found himself at the center of the serve-and-volley toss-up of laying blame and anointing responsibility. His name, once synonymous with all that was fierce, irreverent, and youthful about hip hop was now the very definition of all that was fragile, violent, and immature.

“PUFFY was a ham,” says his mother, before rolling off a litany of examples like a proud stage mother. He modeled with Stephanie Mills in a Wiz layout for Essence. He was a Baskin Robbins ice-cream boy in another spread. But he’d always loved music. “ I didn’t know exactly what he would do, but he was blasting me out of the house with his mixing kit I bought him when he was 13, making that noise, scratching those records.” The house was an apartment in Esplanade Gardens, a middle-class complex in Harlem. Then, when his mother’s work for United Cerebral Palsy forced her to relocate to Westchester County, home became Mount Vernon, a mixed-race suburb just north of the Bronx. His father, who owned a limousine company, died when Puffy was three, and his grandmother raised him with his mother. “My mother was the man of the house,” Puffy says now. “She was running shit.”

But Sean — who became Puffy when he was about 12, in a game of dozens – was looking to the future anyway, to Howard University, where he would find out what being the man was really about. “I knew they had mad girls down there, and parties, but I really wanted to get a black education.” He found our in his first two weeks on campus that there was a world to conquer. “I was looking at things as a businessman by then,” Puffy says, remembering his introduction to black college life. “Experiencing black people from all different lifestyles, different parts of the country. I had to learn from this.”

He had to learn, basically, that it wasn’t who you were but who you knew. He brought his Harlem flavor to bear by throwing parties that became the place to be Friday and Saturday nights on Howard’s campus. “I started gaining friends from that. I could get anything I wanted to on campus,” he says. “If I needed to get my car fixed, I knew where to go. If I needed the English paper, I knew who to go to. If I needed an exam or some weed, I knew how to get it.”

So: schoolwork could be bought; life was easy; Puffy had it made. But he admits now that his methods were suspect. “I had a lot of immature ways about me. I don’t agree with all that stuff now. I had a lot of growing up to do.”

BACK in the late ‘80s, when Puffy was in high school and grooving into the wee hours to the beat of house music and hip hop, artists would come to clubs to film their videos. Puffy found himself dancing for Diana Ross, Fine Young Cannibals, and Babyface. Seventeen years old and hungry for a life in entertainment, he was still confused: Should he be a shaker, doing the Running Man for admiring audiences? Or should he be a mover, actually running things as The Man? When he saw the “Uptown Kickin’ It” video and the young brother named Andre Harrell at the front of the boardroom table, he decided he “wanted to be the guy sitting at the head of the table, pushing contracts aside after signing them.” Heavy D, a fellow Mount Vernonite and a premier artist at Uptown, hooked him up with an interview that landed him an internship working Thursdays and Fridays. Up at five a.m. each Thursday to get to New York by 10, Puffy would make it back to Howard by midnight each Friday for his parties. Even sneaking onto the Amtrak, hiding in the bathroom to avoid paying conductors, he was happy. “I didn’t give a fuck,” he says. “I was at Uptown.”

“My vision for the company,” says Andre Harrell, “was to create a label that was cool, that had that Harlem kind of cool hustler cachet to it.” Puffy impressed Andre, “in his shirt and tie, doing everything right, real polite and respectful.” But what he noticed underneath the polite attire was something else: “Puffy was a hustler.” So when Kurt Woodley, the A&R director at Uptown, left the company, Harrell wasn’t surprised that Puffy took him to lunch and asked to have the job. He was 18 years old.

His first project was Father MC’s debut album, which netted a gold single and respectable sales, carrying on the too-smooth style that became Uptown’s specialty with Heavy D and Guy. But gathering dust were two other projects: Jodeci, a four-man singing group from North Carolina who first record had passed without notice, and future Queen of Hip Hop Soul, a Bronx girl named Mary J. Blige.

Utilizing stereos at high volumes should be limited to VPs and Directors,” reads a memo on the walls of some offices at Uptown Records. Puffy takes this seriously. His office actually vibrates with the force of the beat. As I walk in, Puffy’s on the phone and before he cuts the call short I hear him say, “Nah, G, you think I’m gonna give the merchandising away? I come up with the flavor for my artists.” The flavor for Jodeci and Mary J. Blige, Puffy’s two biggest acts during his tenure as A&R man, came to him as a dream – soulful R&B singers in hip hop gear, a kid of mix-and-match approach that, in retrospect, seems absurdly obvious. A new genre was born. Hip hop soul, as Harrell calls it. Sound meeting sensibility at a typically contradictory African American crossroads. “And now,” says Puffy, “everybody’s trying to look like the groups that I put out, with the images I created.”

Detractors point out that the style Puffy “created” is actually just an extension of his own Harlem homeboy style – that Jodeci, for instance, are just four Puffys onstage, playing out his own narcissism. “I wouldn’t say they’re exactly like me, but it’s a combination of me and young black America,” Puffy says. He stops, ponders for a second, and then continues. “But if I was a honey, I would probably be just like Mary J. Blige. A bitch. Not in the negative connotations of the word but like, ‘That’s a bad bitch.’”

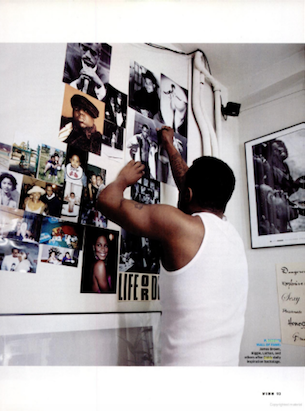

It was in this spare, busy office that the groundwork of the Puffy business occurred. The wall unit holds a small collection of books skewed mostly toward music and black studies, various Uptown artists’ 12-inch singles, and a large color television usually tuned to one video channel or another. A life-size cutout of Mary J. Blige stands at attention near the door, as if to greet visitors with the realization of Puffy’s dreams. A cactus plant, prickly as Puffy often seems, rests on the windowsill. His beeper, on vibrate mode, scurries around his desk like an impatient child; Puffy answers pages constantly. That is, when he isn’t working on the weekly column he writes for Jack the Rapper, an industry journal recounting radio activity of current records. Or when he isn’t meeting with prospective artists, who wait in the anteroom and grin at each other in anticipation of playing their demos for the man who seems to represent the increasing visibility and force of urban black boys in contemporary music. (“I saw him in that Karl Kani ad,” one of them said earlier, outside the office. “Who that nigga think he is?” “Puffy,” responded another, “that’s who.”)

He is remarkably soft-spoken, communicating mostly through body language: He might break into a sliding dance move when describing his night out at Mecca or some other club-of-the moment. Or stand stock-still with a hard-headed stare, daring you to convince him. When a young designer comes in to show a video of his clothing collection, Puffy leaves the room after a glimpse at the screen, refers the video to Sybil, his assistant, then returns to the room and describes, to a T, what he saw only two seconds of.

One day in the summer of ’92, Jodeci needed clothes for a Regis and Kathie Lee appearance. Puffy cabbed from store to store in downtown Manhattan, collecting baggy jeans and woolly skull caps, eating Chinese takeout, chatting into his cellular phone all the while. Late in the day, as I reached for my beeper, he said, “Damn, I never met a nigga get more beeps than I do.” Pause: “I bet you one of those suburban kids, got good grades in school, went to college. You wanna win a Pulitzer prize, don’t you?” This is Puffy: arrogant, boyish competition mixed with the seductive, coy recognition of ambition in others. I ask him later if he is conscious of the seduction. If, in fact, it gets him what he wants. “Anything I’ve wanted, I can say I’ve gotten it,” he says straightforwardly. “I just saw it and did it, you know? I observe. I always look at the situation before I speak and before I decide what I want. I don’t just jump my ass buck naked into the fire pit. I look at that motherfucker and see of there’s any space.

AFTER a long day of listening to demos, scheduling studio time, and preparing for the imminent debut of his own company, Puffy is headed home to the tiny suburb north of Manhattan, in his white BMW, for a much-needed rest. In a contemplative mood, he takes a circuitous route through Harlem, crisscrossing the city streets as if on a memory mission, passing prostitutes on some side streets and lost-looking children on others. Here on the road, caught for a moment between the rare field world of Uptown (the record company) and the rapidly deteriorating world of Uptown (his teenage stomping grounds), he talks about his dark side.

“A lot of my music is about pain. That’s why the masses relate to it. It’s attainable, people understand it. When Mary J. Blige sings about looking for real love, it’s fucked up, searching, you know? It’s realistic shit.”

As he drives up to a stoplight, he says, quietly, “I don’t normally be smiling, real happy, youknowhumsayin’? Ain’t nothing to be happy about. Things are fucked up. You got little kids starving, getting beat up, parents on crack, ain’t got nobody to talk to. The only time I’m really happy is when I’m at a club or the rink and they play one of my records. The motherfuckers be screaming to it. They play one of my remixes and I see the look on their faces. Or I go to the concert and see all the kids dressing and looking like my artists.

“I could have got off on the highway, but I just have to drive through Harlem to remind me about all the fucked-up shit. How fortunate I am.”

THERE’S a story about Puffy that both his detractors and admirers like to tell. When he was a little boy in Mount Vernon, he wanted a pool, refused to swim in the public pool in the park. According to one version, Puffy begged and begged for the pool and was only happy when his mother took on a second job to pay for it. When Puffy tells the story, he describes the white kids across the street and how they teased him. “They would never invite me over. I used to cry. My Moms made sure she got me a pool that was two times bigger than theirs. It took her like a year to save for it and it was the only Christmas gift, nothing else, no socks, nothing.” I ask if he thought he was spoiled. “My mother tried to get me everything I wanted. She always sacrificed and didn’t do it for herself. Maybe by some other standards I was spoiled, but I didn’t think so. I never did no flipping-put brat shit on my mother.”

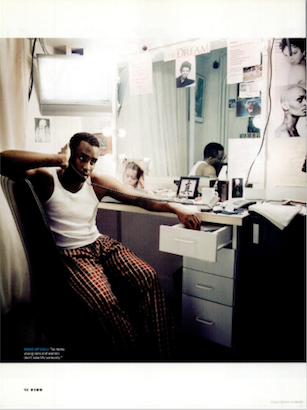

When we get to his house, he tells me he bought it because of the pool. It’s a beautiful split-level, small by the town’s standards, but comfortable. Puffy shares it with his assistants Mark and Lonnie, who each have their own room off the main hall. Puffy’s bedroom is dominated by the closets and roomy, boxy shelf space filled with sneakers and shoes. Downstairs, a pool table takes up most of the space in the rec room, off of which there’s a bar and weight room and mixing room for late night scratching sessions.

Mark and Lonnie come in, carrying records and Puffy’s suit, fresh from Agnes B. Shirts need to be ironed, so Puffy challenges Mark to a game of pool. The loser will iron. “I’ma make you my bitch tonight,” Puffy tells Mark as they square up.

As Puffy wins game after game, the front door opens and his mother come sin, carrying paintings for the house. Everyone calls Mrs. Combs – a short, stylish woman with close-cropped hair – Mom. She eventually takes a seat at the bar and watches the game, telling me about her son’s hustling nature. She tells me about Puffy’s father, about how he was quite the player, the pool shark, how he would shoot pool and dice up around Lenox Avenue and 126th Street, and how Puffy probably gets his spirit, his competitiveness, naturally. Then her Mom-speak breaks in: You should ear if you gonna go out. What are you wearing tonight? You want me to fix y’all some sandwiches? And she does, heaping mounds of Steak-Umms with tomatoes and cheese.

Mark irons, Puffy dresses, Lonnie scratches on the turntables. Boys at home, before they become men in the street.

HIP HOP has always been – and will always be – about fabulousness and myth. It’s about building new stages to perform newer songs while wearing the newest clothes. But from its fitful birth on the cracked pavement that lined the blocks of upper New York City until the mid ‘80s, when Run-D.M.C. rushed up the pop charts with the other American Realness acts (Springsteen, John Cougar Mellencamp), “hip hop” was “rap,” ethnic and subcultural, taken for granted by the kids from around-the-way, dismissed by the High Pop tastemakers with the contempt they reserved for that which they didn’t understand. But there were a few who could keep the equation in their heads. Russell Simmons and Fab 5 Freddy, for instance, saw the “in,” saw the never-quenchable thirst of major labels and downtown art galleries as creating the next, and logical, pit stops for this new, evolving thing. Some called it selling out.

But there was another generation behind them, who could also keep the equation in their heads, as they danced to the residue of black power that seeped through the grooves of Public Enemy and KRS-One records. They were also watching the decade-defining shenanigans on Dynasty and buying into the record-breaking event called Thriller and imbibing the language of bigness, or largeness, as it would be called in hip hop parlance, where words come and got a feverishly junk-bondish turnover rate.

Puffy is from that generation. They know that blackness means fierceness in the face of adversity. They know that they can yell “Fuck white people” or call yourself a “nigga” and make millions. Their first hip hop shows were often stadium-size or live freestyling on, of all places, MTV. They are conscious of their era, and they know they exist because they spend money on entertainment that tells them they exist. And closer to home, they saw that the people with the fresh cars and nice clothes were not parents of kids their age, but actually kids their age, kids with lethally legal and illegal businesses. Gettin’ paid. Livin’ large. Whether on the money-makin’, boogie-down tip of the entertainment world or the hardcore of the street, black people could own. And what better to own and market, to turn into a mock grass-roots cottage industry, than the culture itself? Says one industry insider, “All these young boys wanna ne in the music business to get large, when they would be out in the street selling drugs. The music industry is perfect for them, ‘cause it’s just a legal form of drug dealing.”

Listen to Puffy talk about drive, about the reason he gets up in the morning: “The young kids – all the real motherfuckers across the world that’s young and black – they need that real shit. Motherfuckers need that shit, youknowhumsaying’? They got to hear it. Like, if records stopped being made, motherfuckers would be jumping out of windows or something. That shit is almost like a drug.”

That’s also the reason he started throwing parties.

HIP HOP parties had, for the most part, been banned in New York, due to an increasing amount of violence and recurrent, racist complaints about noise. But Puffy needed a nightlife. Why not just create one? “I found myself being this senior executive of A&R,” he says now, “and I was like, yo, I wanted to use my power and my money and rent some of these clubs, so we could have a place to go.” Kicking off his reputation with a Christmas party in 1989, when he was starting out at Uptown, he threw a fete for the industry, he says, “to kind of announce myself. It was real dope.”

He teamed up with Jessica Rosenblum, a downtown club fixture, who once womaned the door at Nell’s. She’d established a niche for herself by organizing social functions for the music industry and came with a reputation as a white woman on the hip hop make, one of the many white faces popping up more and more frequently on the scene. She and Puffy became partners with the opening of Daddy’s House as the Red Zone, a home for hardcore hip hop where you could roll with the flavor to the latest beats, complete with live shows and plenty of attitude. “We were equal partners,” Puffy says, “but I was more on the creative end, I knew more of the people.” Daddy’s House received the imprimatur of the hip hop tastemakers and Puff Daddy became synonymous with the hippest underground jams in New York City. Rosenblum describes Daddy’s House this way: “You know a party is a success when it turns up in a rap song. Daddy’s House did.”

But its success was short-lived. Fights began to break out. Jessica wanted to expand her own operation. Puffy had a regular job, with increasing responsibility. “It just started to become too much pressure for me,” he says now. “And I was making money from work. I didn’t want party promotions to be the main thing in my life.”

But in December of 1991, one particular party would become the only thing in his life.

IT all started when Magic Johnson announced he was HIV-positive. Puffy was upset and wanted to host a celebrity basketball game to raise both money and community awareness. Well-practiced by now in the art of promotion, on the day of the game Puffy had everything running smoothly. Heavy D had gotten involved in the plans, and by late afternoon a posse of usually reticent artists – Boyz II Men, Mary J. Blige, Jodeci, Michael Bivins, EPMD – and hundreds of fans had shown up at the Nat Holman Gym.

“As it started getting dark, we had to shut the doors cause the line had got disorganized out front,” Puffy says. “The police came in through the back door and we were like, ‘Yo, there’s too many people out there.’ We told them we really needed their help. This white sergeant said okay and they all left the building out through the back and then like about an hour later, the people in the pay line started pushing on the doors. Inside the gym, it was only 40 percent capacity filled. But we weren’t gonna let nobody else in. Anybody who got caught outside with tickets, we were gonna refund their money. We just didn’t wanna take chances by opening the doors back up.

“But people started pushing from the outside and the doors just snapped off the hinges and people just started pouring in. People started jumping down the staircase. People started piling on top of each other and glass started breaking in the doors and people were getting scared and running.

“Pushing and pushing. It was more pressure. Then all of a sudden, I’m on the other side of the door, pulling people through so we could open some of the other doors, but even as we started pulling people in, more people were pushing through. We started screaming to people to get back, to back up. And like a few minutes later, we saw people passing out cause of the heat.”

He pauses, drawing in a breath. “And we started seeing some scary shit. People’s eyes were going back in their heads and I’m thinking, people could die out here. A big kid had gotten stuck in the door and we couldn’t pull him through or anybody else. The cops were being called, but nobody was coming.

“And I could just feel it. I was thinking some of the people were dying or dead. People had started to regurgitate. Nobody was trying to give mouth-to-mouth resucitation, so I started and other people started. One guy that I knew, we were trying to revive him for like 45 minutes. He was throwing up in my mouth but I didn’t care. We were like, Yo, man, you gotta live. We were pumping his chest and breathing into him. And I’m seeing my girlfriend buggin’ out because her best friend is there, not breathing, and I’m trying to give her mouth to mouth. And I start to feel this feeling, in the breath I’m getting back, that people were dead. I could feel the death going into me.

“Later,” he continues, his voice quietest now, “I went home, and I kept saying to myself that it was all a bad dream, that I was gonna wake up. But I never woke up. And the next day we contacted the police and the mayor’s office. But people just looked at the flyer and saw my name and Heavy D’s name and started blaming everybody, people saying whoever threw the event must have fucked up. And the press started drawing conclusions before the actual investigation.”

Accusations flew from all corners. The director of the student center at City College blamed the president of the Evening Student Government, claiming in the New York Times that she had misled him about “her skill in organizing such events, the size of the expected crowd and to whom the proceeds were to be donated.” It turned out, also, that the AIDS Education Outreach Program, the charity to which a portion of the proceeds were to have gone, was questionable. It had not been registered as a charity in Albany, according to the Times, and “was not known among anti-AIDS groups.”

In televised press conferences, Puffy looked shrunken and young, hesitant in speech and demeanor. He went underground to avoid ensuing melee of judgement. Even Rosenblum, whom Puffy had hired to work the door (not to co-promote, as was rumored), admits that the situation took its toll on him. “It made him learn to think things through,” says Rosenblum now. “Puffy’s used to telling people what he wants and having them execute it. Unfortunately, this time, the people working for him didn’t fully execute the plan. It wasn’t Puffy’s fault, but it was his responsibility.

Says Puffy, “I started to lose it. I felt like I didn’t want to even live no more. I was so fucking sad. The legal counsel was not to go anywhere, not to talk to anybody. But I wanted to go to the wakes and funerals and try to provide some comfort, even though I knew my presence probably wouldn’t have given comfort. But what I was going through, with the blame and stuff, was nothing compared to what the families were going through.

“I couldn’t eat,” he recalls now, sitting forward in his seat. “I was just sleeping, like a mummy. I didn’t talk to nobody. And every time I turned on the news there was something about the event of the money or something.

“I was scared throughout the whole event. There’s no big hero story to all this. I’d never had that much up against me. I had to be a man or die. And I was deserted. There was like, fake, nosy support. But a lot of people I thought were my friends just fell by the wayside. I had my mother and my girl and Andre, and a few other friends.

“But I have to live with the fact that people meet me or see me and no matter how many platinum records I have or whatever, they’ll think, ‘Oh, that’s the guy who murdered nine people at City College.’ Cause they didn’t check out the mayor’s report that cleared me of all the blame. [The City Hall report actually found that Combs had delegated responsibilities to inexperienced associates and should have arranged better security to handle the expected large crowds.] But I imagine the pain the families go through and I understand that what I went through and will go through is nowhere near their pain. And that’s the thing that kept me going, knowing if they had the strength to go on, I had the strength to go on and handle people looking at me and thinking whatever they’re gonna think.”

“The City College event grew him up quick,” Heavy D says. “He was on a path where he could have destroyed himself. He was on a high, you know, he was ‘Puffy!’ doing all this stuff at his age. But every disaster has a delight. There’s a lesson in disguise.”

Always a “panicky young man,” as Heavy D describes him, Puffy no longer moved with the same reckless abandon, rushing headlong toward whatever goal he set. And even though outsiders looked to place blame on easy official targets like City College or the police, Puff found the answer in the community that bred his style, in his music, himself. “It wasn’t that tickets were oversold like people said. It wasn’t the fire department’s fault or the cops’. And it wasn’t simply that ‘niggas are crazy,’ as people say,” he says. “It’s just that overall in the black community there’s a lack of self-love. The majority of the kids weren’t necessarily gonna put themselves in the position to get hurt, but when ti came time to love their neighbors and move back, they couldn’t love their neighbors because they didn’t love themselves.”

And that’s probably the hardest thing for Puffy to accept: that, in essence, The City itself was responsible for the nine deaths forever linked to his name – The City and its dark side, which feeds on the constant restlessness of the shut-out and put-down, which takes away the places of recreation that might be a respite from the infrequent, hyped “events” kids are attracted to, the places where their heroes can shine bright and strong.

BUT Puffy’s job was to create those heroes, and he had to go back to work soon after the tragedy. Jodeci and Mary J. Blige were blowing up around the country and bringing a whole new image of young blackness to the masses. Mary J. Blige’s blasé, Uptown Girl attitude mixed with hip hop beats, and a talent show vocal aggressiveness redefined the concept of the soul-shouting diva. Puffy was also at work on Blue Funk, Heavy D’s darkest album, full of pain of love lost and maturity gained. Jodeci became the standard-bearer of urban black-boy stoicism, but with a supple, gospel sound that made R&B edgy again.

And edginess is what Puffy likes. In the works was Bad Boy Entertainment, Puffy’s own management and record company. During the aftermath of City College, says his mother, “A lot of people showed Sean there asses to kiss. I was there for him, and we became a lot closer, we started communicating better.” She realized just how determined her son was about having his own company. “I didn’t want him going down the drain,” Mrs. Combs says now. “I told him not to worry, that we’d have our own thing. I had planned to help him all along, but this seemed like a good time. I invested in something for him.”

“Puffy is a warrior, he’ll go for his,” say Andre Harrell. Sean wants Bad Boy to embody to his own personal energy and philosophies. Bad Boy wants to be edgier, harder. They would sign a gangster rapper. I think Puffy wants to deal with more rebellious issues.”

I ask Andre about Puffy’s rebellion thing. He laughs and outlines his Theory of Black Folks: There are “ghetto negroes, then colored negroes who are upper lower class or lower middle class who want to go to college and feel the need to be dressed up everywhere they go, you know, working with the system so the system will work for them. Then there’s just Negroes, saying’, I’ve had a credit card for ten years, my father went to college. Puffy is somewhere between ghetto and colored. He is very much like Russell [Simmons]. Puffy was raised colored, went to private school. And that’s why he wants to be rebellious. He didn’t grow up where rebellious was just normal. Colored folks want to be down with the ghetto.”

LATE one Sunday night, Puffy and I sit in his white BMW, on East 21st Street in Manhattan, and I ask him about the ghetto thing and its influence on his music. He tells me that even though he didn’t grow up in the projects, he was “always attracted to motherfuckers who were real, niggas who really didn’t have a lot. Like, a person could live in the suburbs, but they may not have no friends there. You don’t really have nothing if you don’t have no friends and your mother is a single parent and she may never be around and you ain’t really got shit.”

“Are you talking about yourself?”

“Yeah, in a sense. But the majority of kids in the suburbs was made, you know? Their parents made them a certain way. These kids from the ghetto had no choice. They didn’t have shit, but they were real.”

Finally he boils it down to its essence: “I don’t like no goody-two-shoe shit. I like the sense of being in trouble. It’s almost like a girl, youknowhumsayin’? Girls don’t like no good niggas. Girls like bad boys.”

Heavy D believes that Puffy – the persistent kid from around the way, who found that all his dreams and nightmares could merge in a single moment – is “slowly yet surely realizing that what he has is a gift. In my opinion, Puffy was responsible for Father MC, Mary J. Blige and Jodeci. Especially Jodeci. You gotta remember that they had a record out before, and they only blow up when Puffy got in the loop. But Puffy has to realize that that gift ain’t for him. It’s for other people.”

With the debut of the Bad Boy artists, Puffy’s ultimate test awaits him. The four acts on the roster are acts hand-picked by Puff Daddy himself, not acts passed down for his overseeing. Although the first release, Notorious Big’s “Party and Bullshit,” featured on Who’s the Man? soundtrack, has an irresistible street flavor that seems to have caught the attention of the party people, it remains to be seen whether Puffy has the ears to go with his eyes, whether he can see a project from its inception to its fruition with the same level of success. Faith, it seems, will show him the way.

Sitting in the car on 21st Street, Puffy is preparing to go into Soundtrack studios to remix Mary J. Blige’s next single. Perhaps that, and recounting the City College nightmare, explains the sudden darkness in his manner. He leans back in the leather seat and sighs. “I just like talking to God, realizing that my shit ain’t nothing, my problems are so minute. I pray every night, every day, I talk to God a lot. I carry a Bible with me all the time.”

He pulls a tiny, tattered, dog-eared Bible from his back pocket and turns to Psalms. He reads: “The Lord is my light and my salvation; whom shall I fear? The Lord is the strength of my life; of whom shall I be afraid? When the wicked, even my enemies and my foes, came upon me to eat at my flesh, they stumbled and fell.”

This is the text of Puffy’s next tattoo.

EPILOGUE: Whatever the reason for Puffy’s dismissal from Uptown – and we may never know the real reason, or, for that matter, the true nature of the relationship between Puff Daddy and Andre Harrell – both men continue to speak well of each other. Harrell’s Uptown will continue to oversee the development of Bad Boy’s first three artists – at Puffy’s request. Puffy will retain the Bad Boy concept and has the freedom to develop his dream elsewhere.

Just three days after being fired, Puffy remained his cool and contained self. “My only regret,” he says, quietly, patiently, “is that if I had any flaws, I could have been nurtured or corrected, instead of people giving up on me. Somebody older may think I have nothing to be angry about ‘cause I did what they did in half the time. But I’m not ungrateful for what I’ve received.” He sighs, “But this is just another chapter. This ain’t no sad ending.”

And he is right. It won’t be long before there is yet another Puffy story to tell.

Read the Post

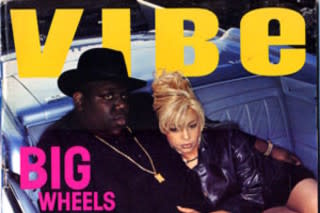

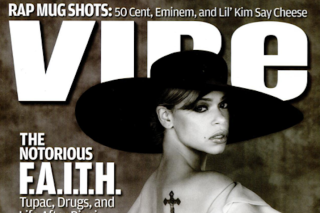

BIG Wheels: Rollin' With The Notorious B.I.G. And Faith

The Evolution Of Sean “Puff Daddy” Combs And The Bad Boy Family Through VIBE’s Covers

BIG Wheels: Rollin' With The Notorious B.I.G. And Faith

THINGS DONE CHANGED

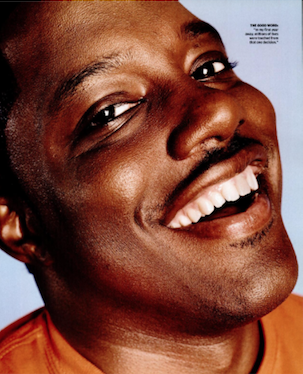

Written By: Mimi Valdes

Photographs By: Eric Johnson

Issue: October 1995

Back when he dropped his debut, Brooklyn’s own Notorious B.I.G. was Ready to Die. Now he’s got a No. 1 single, a platinum album, a loving wife, and everything to live for. Mimi Valdes goes on tour with the hip hop giant to answer the question, How ya livin’, Biggie Smalls?

“I didn’t know he was going to be this large,” says Mark “Gucci Don” Pitts, the Notorious B.I.G.’s manager, driving the black Lexus that doubles as his office. Pitts, 25, is a former employee of Sean “Puffy” Combs’s Bad Boy Entertainment who left to represent Biggie independently in 1993. “Damn,” he says, thinking back on the past 24 months, “I can’t believe we blew up that quick.”

And he’s not the only one who’s surprised. “That star shit ain’t really hit me until a couple of months ago,” says 22-year-old Biggie Smalls, a.k.a. the Notorious B.I.G. Who could have predicted that the Brooklyn native would throw New York hip hop back into the spotlight? He’s the East Coast messiah; even KRS-One (he of the legendary skills and equally legendary ego) says it’s true. Biggie’s album, Ready to Die, is nearly a year old and still up there on the charts.

His first single, “Juicy,” went gold. “Big Poppa” went platinum. And the souped-up “Ome More Chance/The What (Remix)” had been sitting atop the R&B charts for six weeks at press time. Michael Jackson even asked him to rhyme on HIStory. No doubt, B.I.G. is more than large.

Christopher Wallace was born the only child of a Jamaican single mom. The two have always lived in the same flat in the Bedford-Stuyvestant area until this year, when Big moved into a duplex with his wife, singer Faith Evans, and her daughter. Before his rap career, Big didn’t give a fuck about anything – just look at what he named his album. “It was a lot of hard work, getting him serious about business,” says Pitts. Big remembers how Pitts helped him through the transition: “Mark used to come to my crib, and I’d be, like, ‘Fuck you, I ain’t doing shit.” But he’d take a hot rag, wipe my face, and help me up.”

Biggie’s financial situation didn’t make things any easier. “When I stopped hustling and started making songs, it was the worst,” he says. “My advance from Bad Boy was just petty money, like 12, 20 G’s” – nothing in comparison with the “money money” that he was used to back when he was selling drugs.

Most of Biggie’s money these days comes from live shows; he’s been touring steadily throughout the past year, picking up $20,000 per performance. “Big understands what he has to do, and being on the road is part of that,” says Hawk, who grew up down the block from Big and is now his road manager. Biggie rolls with a tight crew of seven or eight whom he considers “family.” It’s a good thing they’re so tight, because life on the road – shady promoters, broken-down tour buses, weed shortages, and too much McDonald’s – can get hectic.

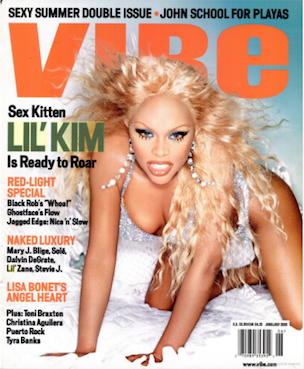

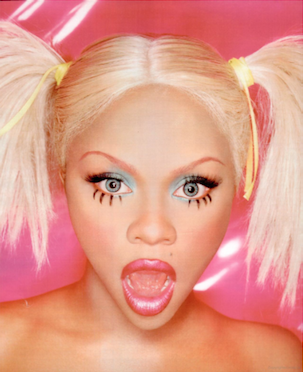

BIG doesn’t do much to prepare for this evening’s concert in Raleigh, N.C. – besides maybe smoking a few blunts. Wearing navy blue Sergio Tachini track pants and no shirt, he’s watching TV with Little Kim, the fly female MC from Junior M.A.F.I.A. (Big’s longtime partners and protégés). Although she calls herself Big Momma on “Player’s Anthem,” Kim, who’s actually slim and petite, is concerned that Big Poppa may be a little too bit.

“I’ve never thought about losing weight,” says Biggie.

“I just want you to be healthy,” Kim pleads, laughing.

“Healthy, schmealthy. How much you think I should weigh?”

“A hundred and eighty,” she says. But when the six-foot-three MC lets her know his weight (315 pounds), Kim reconsiders.

“Two hundred, then. I didn’t know you weighed that much.”

It’s after 11 p.m. when Big, now wearing a custom made 5001 Flavors linen suit, steps onstage at Club Rhythms. The stage is actually outdoors, facing a forest, a fence, and 500 fans standing on gravel, ready to go wild. By Big’s side are Little Ceasar (from Junior M.A.F.I.A.), Money-L (the hype man), and D-Rock (his right-hand man), who’s videotaping the show. And there’s a lot to capture: girls in front rubbing their titties during “Player’s Anthem,” kids sitting in trees outside the club pumping their fists, and chaos when 200 one-dollar bills are thrown into the audience during “Gimmie The Loot,” (Biggie used to throw the money himself until he lost a $5,000 ring Faith gave him.)

After the concert, more than two dozen cars play follow-the-white-stretch-limousine. At the hotel, Big rushes to his room while his crew wait to see who’s in the cars. A few girls in evening gowns make their way inside. “I don’t want him to think we came to do the do-it,” says one autograph seeker. After standing around for a while, she and her crew decide he ain’t coming out. They leave, but some scantily clad girls linger.

But Big ain’t trying to fuck with any chicken heads. Although there are rumors that his marriage to Faith was a publicity stunt, or that it was recently annulled, they’re totally false. The pair celebrated their first wedding anniversary on August 4, and are very much in love. At the video shoot for Faith’s “You Used To Love Me,” they could be seen giggling and calling each other nicknames (he’s Riccardo, she’s Moschino). They met at a Bad Boy photo shoot last summer and were married nine days later. “I had my share of all kinds of women,” says Big. “I can’t explain it. I just knew Faith was different. I wanted her locked down.”

Of course, his friends were buggin’, especially his mom. Everyone believed she married him for his loochie, though at the time, Faith actually had more money than him because of her songwriting and background vocal work for the likes of Mary J. Blige, Color Me Badd, and Pebbles. “I’m, like, ‘Ma, what money? I owe you $300,’” says Biggie, laughing.

As serious as Big is about his “baby,” she’s just as serious about him. One night after a show in Virginia, Big was arguing on the phone with Faith, who was in New York. He hung up, and when she tried to call back, Big refused to answer. Later, some girls came to the hotel and coupled off with Biggie’s boys. One was left out, and Big allowed her to sleep in his room. “It was some completely innocent shit,” insists Big. “We weren’t fucking.” They awoke at 8 in the morning to a knock on the door.

“The girl’s, like, ‘Who is it?’” he recalls, “and a sweet voice says, ‘Housekeeping,’ She opened the door, and Faith beat the shit out of her. Oh my God. Punched homegirl in the face about 30 times, then got on the next flight back to New York.” Big was lying in bed speechless the whole time. “I was, like, Oh shit, that’s the illest right there,” he remembers. But Faith made her point: “I was so nervous, I jetted to New York ‘cause I wasn’t gonna leave her buck-wil’ing like that. The girl was mad cool and I felt horrible, but fuck that. I got on that plane.”

For Biggie, being away from Faith is one of the hardest things about touring, but he’s got to get the paper. “I still haven’t gotten money from the album itself,” says Big. “I spent a lot, and the label has to recoup first. That’s why I sold half my publishing to Puffy. I was br-zoke, and if a nigga could make a quick quarter of a million just from signing a few papers, you gotta let it go.” Puffy may have hit him off with a nice chunk, but it’s nothing compared with what Big might’ve made had he struck a publishing deal after he blew up. Some may say Big got jerked, but then again, Puffy is very much responsible for his success.

Biggie wanted his first single to be “Machine Gun Funk,” but Puffy knew which songs would take him to a wider audience. “Puffy was on some, ‘Yo, let’s get rich. If we drop “Juicy,” you’ll have a gold single,’” recalls Biggie. Puffy compromised by letting him do an ill B-side. “If people weren’t with ‘Juicy,’ they could turn it over and hear ‘Unbelievable,’” says Biggie. “My niggas weren’t mad at me, so I was straight.” Puffy wanted to drop “Big Poppa” next. “I was, like, Oh man,” says Biggie, rolling his eyes. “But then Puffy started talking that money shit again.”

AFTER a 12-hour bus ride from Raleigh to Cleveland, and three stops at McDonald’s, Big’s getting set for tonight’s concert. The smoke detector in his room has been covered with a towel so his King Edward blunts won’t set off any alarms. “I’m feeling kind of sluggish,” he says. “Maybe it’s because I didn’t take no vitamins today.” He’s referring to his jar off yohimbe pills (made from African yohimbe trees) that promise “ultra strength, stamina, and energy.” After brushing his teeth near the TV, spraying on some Guy LaRoche cologne, and applying deodorant, Big’s ready. Two white limos bring everyone to the Gund Arena, which is like three minutes away.

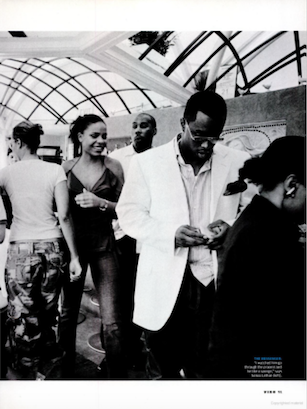

Once inside, the entourage head straight to their dressing rooms. A few minutes before he’s supposed to go on, Big decides to step to the backstage area, which is visible to some fans. Women of all shapes, sizes, and colors lose their minds the moment he appears. “Big Poppa, Big Poppa,” screams one beautiful sister. “Please, please, please, please come over here so I can feel you,” yells another.

Though Ice Cube is headlining – on a bill that also includes Naughty by Nature, Heather B., and Kut Klose – Big steals the show. The crowd goes wild during “Big Poppa” and when DJ Enuff drops the beat for “Can’t You See” and Big starts his rhyme, the arena explodes. But when surprise guest stars Total begin singing, the vibe just dies. By the time they get to the chorus, someone has thrown water at one of the girls when Total finish, pennies and a half-eaten hot dog litter the stage. But Big picks up the pace and leaves the crowd wanting more before closing with “One More Chance” as an encore.

Back at the hotel, it’s all chilling and cracking jokes. Because of Big’s size and demeanor, many would be surprised to learn that he’s a straight-up comedian. “I definitely can make a motherfucker laugh,” he admits. He gets all excited about a black female contestant on Jeopardy’s Senior Week: “Yo, you missed the introductions. Mama sais she was from Bed-Stuy, representing BK to the fullest.,” Big tells his boys, who knows he’s lying. “I swear. She even said she wanted to give a shout-out to Biggie Smalls!”

When he recalls the surreal experience of meeting Michael Jackson, he can’t stop laughing. “When I found out he wanted to do a joint with me, that just tickled me pink,” says Big, who flew to the session in L.A. almost immediately. He heard the track for “This Time Around,” knocked out the vocals, and was ready to bounce when he heard Jackson wanted to meet him. “I was, like, ‘Do you like it? Make sure you use it. Please,’” says Biggie, who’s hoping the song gets released as a single. “Just imagine us playing C-Lo in the video. It would be over.”

Five minutes after getting on the highway to Chicago from Cleveland, the bus runs out of gas. As the driver disappears to get help, the crew chat on their cellulars and play spades for $200 a game. It’s almost five hours later when the bus finally moves, and close to midnight before it arrives in Chicago. Everyone’s tired and hungry, but happy they’ll be in the city for three days and can finally do some laundry. “I ain’t got no draws,” complains Big.

The next day, the promoter takes everyone out to a couple of malls in a white van. Biggie’s looking for Versace shades but instead settles for five pairs of multicolored Coogie socks at $17.50 each. At the counter, he flips through the Coogie housewares catalog of blankets, pillows, and curtains. “I can’t wait to get my house,” says Big. “I’m gonna get all this shit.”

As soon as Big gets some of his big checks, he’s buying his moms a house in Florida and moving out of Brooklyn with a quickness. “I’d be a fool-ass nigga to sit in the ‘hood, on top of millions, thinking about nothing ain’t gonna happen to me,” says Biggie. But what about keeping it real by staying in the ghetto? “Keeping it real is taking care of your family,” he says, “not taking all that money and doing stupid shit.” That’s why Big has a screenplay in the works, plans to open a chain of 24-hour diners called Big Poppa’s, maybe even start a clothing company for big me. “I got the cars, the jewelry, the clothes,” he says. “Not it’s time to do something with money instead of just spending it.”

After the mall, it’s off to a steak house, where the crew sit down to their first real meal in days. But when the check arrives, the promoter refuses to pay. Later that night, hotel personnel inform everyone that their rooms haven’t been paid for either. The next day there are pins in everybody’s doors, preventing them from using their keys. The promoter’s actions are worthy of a beatdown, but Big’s crew know better.

You see, Big don’t get down like that. That’s why his recent arrest on assault charges is so unbelievable. Ain’t nobody trying to hear that bullshit about rappers happy to be locked up ‘cause they’ll sell more records. “I’d rather be dead than in jail,” says Biggie. “That shit is the worst. I was shaking, throwing up, ‘cause the shit was mad dirty, mice and rats all over.” Not the place for an MC who wants Coogie down to the socks, caviar for breakfast, and champagne bubble baths.

On May 6, Biggie was supposed to do a show in Camden, N.J., but when he got to Club Xscape, the promoter (and Big’s money) could not be found. Pitts told Nate Banks Jr., who had brought Biggie to the club, to take them to see the promoter. Upset ticket holders followed Big in their own cars, joining the mission to find the promoter. When the caravan reached the promoter’s crib, his brother came outside to say he wasn’t home. According to Banks’s attorney, Banks was then beaten up and robbed of his necklace, bracelet, watch, cellular phone, beeper, and $300 in cash. “When he was down, Christopher Wallace comes across the street and kicks him in the head,” the attorney adds.

“I saw the commotion,” says Biggie. “I got out my truck, Mark said, ‘Get the fuck back in the truck,’ and I did.” Exactly who beat Banks down – and when – remains unclear.

Six weeks later, after a show near Philly, Biggie and crew jumped in their rides to leave. Outside the parking lot, they noticed flares on the ground and policemen giving directions. “We’re thinking it’s a police escort ‘cause there were so many people outside the club,” says Biggie. “They lead us to a lot and – whoo, hoo. I swear on my daughter, niggas rolled out the bushes on their stomachs and pointed rifles with infrared beams on my truck. Meanwhile, I’m in the passenger seat with a bottle of Dom Perignon, pissy drunk, like, What the fuck is going on?” No one in Biggie’s circle even knew that there was a warrant out for his arrest.

“They got me on my belly, in the grass, with mad bugs crawling on my face,” recalls Biggie. “Next thing you know, one guy got the shotty with the flashlight on the tip leaning on my head. They took me to the precinct and niggas were giving each other high fives and doing belly slaps. I’m looking at them like they crazy.” The copes even asked him to sign autographs.

Biggie was held in jail for three days before being released; he then turned himself in to Camden police. His trial date has yet to be set. “Somebody told me I should just give duke [Banks] some money,” he says. “Whatever, man. I’ll see that nigga in court.”

The whole ordeal, however, pit a temporary strain on Big’s relationship with his mom, a Jehovah’s Witness. “That shit made her think of the old Christopher, like I was still on the same bullshit,” Biggie says. “I’m telling her that I didn’t hit him, I didn’t rob him, and she looking at me, like, Whatever. I mean, that’s my ol’ MO, you know what I’m saying?”

“Things done changed,” raps Biggie on his debut album, and that song has since taken on a multitude of meanings. Yes, he went from negative to positive, but nothing’s ever all good. A few years ago the possibility of prison was an occupational hazard, but at least he knew the risks. Now that he’s turned his life around, he’s got a whole new set of problems to worry about.

Biggie says he’s “the same ol’ nigga – maybe a little but more bossy.” The letters of his stage name used to just mean “big.” Now he likes to say they stand for “Business Instead of Game.” And if he was Ready to Die two years ago, now he’s got everything to live for. He know it too. He’s already decided on a title for his next album. It will be called Life After Death. ~ Mimi Valdez

~~~~~~~

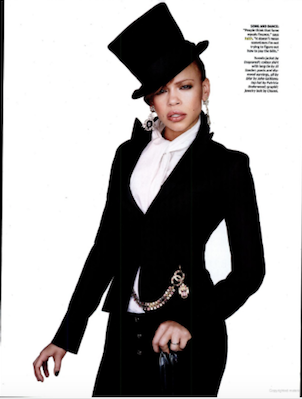

YOU GOTTA HAVE FAITH

Written By: Emil Wilbekin

“I asked for it,” says Faith Evans, laughing at the thought of her crazy, busy life. “I knew what I was getting into.”

And the 22-year-old singer of the hit “You Used To Love Me” ain’t lyin’ – she keeps a hectic schedule. On any day, the ghetto chanteuse might be getting her weave done, paying her bills, talking on the phone with Biggie, feeding her two-year-old daughter Chyna, making travel arrangements, and trying to keep it all together – all at the same time.

It isn’t easy, but it’s fun,” she says. “I wanted a child, a husband, a career. I’m on e of those people who always has my hand in everything.”

That’s how her musical career began. “I started singing when I was two at my church in Newark,” Faith says. “I don’t remember how I ended up at the mike, but I sang a song I heard on The Flintstones: ‘Let the Sunshine In.’ That was my little debut thing.”

She didn’t stop there. Faith appeared in high school musicals, studied jazz and classical music, and even ended up with a New Jersey Miss Fashion Teen title. Then the high school honor student started at Fordham University on an academic scholarship, majoring in marketing. After a year, though, she left to market herself.

And it’s worked. Aside from sounding lovely on her self-titled first album, Faith’s stirring voice can be heard on Biggie’s “One More Chance.” Plus she’s written songs for chart-busters like Mary J. Blige and Color Me Badd. In fact, it was while working on Usher’s debut album that Puffy Combs got sparked by her skills and signed her. She’s been upward bound ever since.

While Faith’s voice conjures a resonant mix of Minnie Riperton, Ella Fitzgerald, and Chaka Khan, she’s most often compared to May. But the sultry songstress shakes her head at that notion. Despite the platinum blond hair, pouty lips, and Puffy connection, Miss Faith has her own style. “Me and my album,” she says, grinning, “can’t even be categorized.”

Read the Post

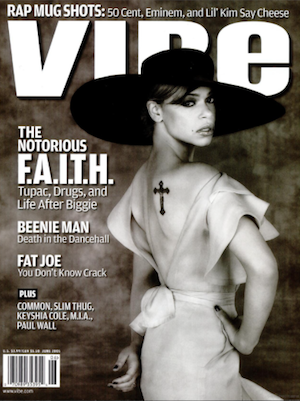

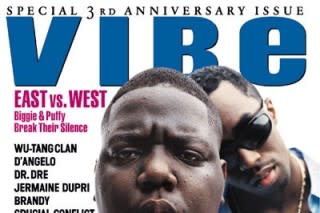

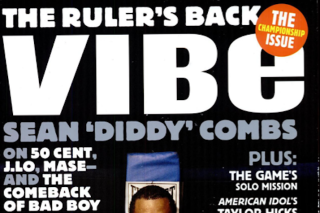

East vs. West: Biggie & Puffy Break Their Silence

The Evolution Of Sean “Puff Daddy” Combs And The Bad Boy Family Through VIBE’s Covers

East vs. West: Biggie & Puffy Break Their Silence

STAKES IS HIGH

Puffy and Biggie break their silence on Tupac, Death Row, and all the East-West friction. A tale of bad boys and bad men.

Words By: Larry “The Blackspot” Hester

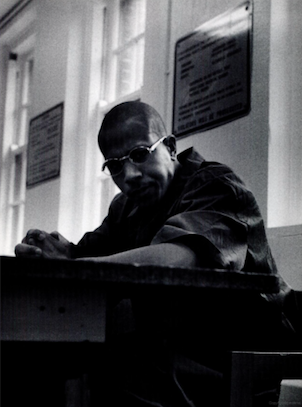

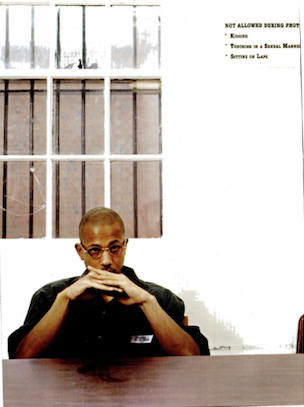

Photographs By: Dana Lixenberg

Issue: September 1996

Now, we can settle this like we got some class, or we can get into some gangster shit. –Max Julien as Goldie in The Mack

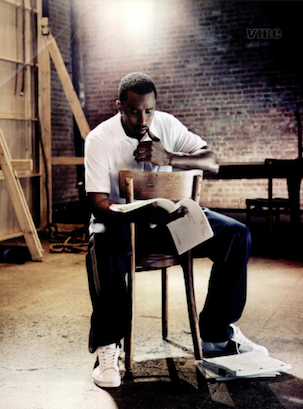

It’s hard to believe that someone who has seen so much could have such young eyes. But the eyes of Sean “Puffy” Combs, bright, brown, and alert, reflect the stubborn innocence of childhood. His voice, however, tells another story. Sitting inside the control room of Daddy’s House Studios in Midtown Manhattan, dressed in an Orlando Magic jersey and linen slacks, Puffy speaks in low, measured tones, almost whispering.

“I’m hurt a little bit spiritually by all the negativity, by this whole Death Row-Bad Boy shit,” says Puffy, president of Bad Boy Entertainment, one of the most powerful creative forces in black music today. And these days, one of the most tormented. “I’m hurt that out of all my accomplishments, it’s like I’m always getting my most fame from negative drama. It’s not like the young man that was in the industry for six years, won the ASCAP Songwriter of the Year, and every record he put out went at least gold…All that gets overshadowed. How it got to this point, I really don’t know. I’m still trying to figure it out.”

So is everyone else. What’s clear is that a series of incidents—Tupac Shakur catching bullets at a New York studio in November ’94, a close friend of Death Row CEO Suge Knight being killed at an Atlanta party in September ’95, the Notorious B.I.G. and Tupac facing off after the Soul Train Music Awards in L.A. this past March—have led to much finger-pointing and confusion. People with little or no connection to Death Row or Bad Boy are choosing up sides. From the Atlantic to the Pacific, hip hop heads are proclaiming their “California Love” or exclaiming that the “the East is in the house” with the loyalty of newly initiated gang members. As Dr. Dre put it, “Pretty soon, niggaz from the East Coast ain’t gonna be able to come out here and be safe. And vice versa.”

Meanwhile, the two camps that have the power to put an end to it all have yet to work out their differences. Moreover, Suge Knight’s Death Row camp, while publicly claiming there is no beef, has continued to aggravate the situation: first, by making snide public comments about the Bad Boy family, and second, by releasing product that makes the old Dre-vs.-Eazy conflict look tame. The intro to the video for the Tupac/Snoop Doggy Dogg song “2 of Americaz Most Wanted” features two characters named Pig and Buff who are accused of setting up Tupac and are then confronted in their office. And the now infamous B-Side, “Hit Em Up,” finds Tupac, in a fit of rage, telling Biggie, “I fucked your bitch, you fat motherfucker,” and then threatening to wipe out all of Bad Boy’s staff and affiliates.

While the records fly off the shelves and the streets get hotter, Puffy and Big have remained largely silent. Both say they’ve been reluctant to discuss the drama because the media and the public have blown it out of proportion. At press time, there were rumors festering that Puffy—who was briefly hospitalized June 30 for a cut arm—had tried to commit suicide, causing many to wonder if the pressure had become too much. Determined to put an end to all the gossip, Puffy and Big have decided to tell their side.

“Why would I set a nigga up to get shot?” says Puffy. “If I’ma set a nigga up, which I would never do, I ain’t gonna be in the country, I’ma be in Bolivia somewhere.” Once again, Puffy is answering accusations that he had something to do with Shakur’s shooting at New York’s Quad Recording Studio, the event that sowed the seeds of Tupac’s beef with the East.

In April 1995, Tupac told VIBE that moments after he was ambushed and shot in the building’s lobby, he took the elevator up to the studio, where he saw about 40 people, including Biggie and Puffy. “Nobody approached me. I noticed that nobody would look at me,” said Tupac, suggesting that the people in the room knew he was going to be shot. In “Hit ‘Em Up,” Tupac does more than suggest, rapping, “Who shot me? But ya punks didn’t finish/Now you’re about to feel the wrath of a menace.”

But Puffy says Tupac’s barking up the wrong tree: “He ain’t mad at the niggas that shot him; he knows where they’re at. He knows who shot him. If you ask him, he knows, and everybody in the street knows, and he’s not stepping to them, because knows that he’s not gonna et away with that shit. To me, that’s some real sucker shit. Be mad at everybody, man; don’t be using niggas as scapegoats. We know that he’s a nice guy from New York. All shit aside, Tupac is a nice, good-hearted guy.”

Taking a break from recording a new joint for his upcoming album, Life After Death, Big sinks into the studio’s sofa in a blue Sergio Tacchini running suit that swishes with his every movement. He is visibly bothered by the lingering accusations. “I’m still thinking this nigga’s my man,” says Big, who first met Tupac in 1993 during the shooting of John Singleton’s Poetic Justice. “This shit’s just got to be talk, that’s all I kept saying to myself. I can’t believe he would think that I would shit on him like that.”

He recalls that on the movie set, Tupac kept playing Big’s first single, “Party and Bullshit.” Flattered, he met Tupac at his home in L.A., where the two hung out, puffed lah, and chilled. “I always thought it to be like a Gemini thing,” he says. “We just clicked off the top and were cool ever since.” Despite all the talk, Big claims he remained loyal to his partner in rhyme through thick and thin. Honestly, I didn’t have no problem with the nigga,” Big says. “There’s shit that muthafuckas don’t know. I saw situations and how shit was going, and I tried to school the nigga. I was there when he bought his first Rolex, but I wasn’t in the position to be rolling like that. I think Tupac felt more comfortable with the dudes he was hanging with because they had just as much money as him.

“He can’t front on me, “ says Big. “As much as he may come off as some Biggie hater, he knows. Kne knows when all that hit was going down, I was schooling a nigga to certain things, me and [Live Squad rapper] Stretch—God bless the grave. But he chose to do the things he wanted to do. There wasn’t nothing I could do, but it wasn’t like he wasn’t my man.

While Tupac was taking shots at Biggie—claiming he’d bit his “player style and sound—Suge was cooking up his own beef with Bad Boy. At the Source Awards in August 1995, Suge made the now legendary announcement, “If you don’t want the owner of your label on your album or in your video or on your tour, come sign with Death Row.” Obviously directed at Puffy’s high-profile role in his artists’ careers, the remark came as a shock. “I couldn’t believe what he said,” Puffy recalls. “I thought we was boys.” All the same, when it came time for Puffy to present an award, he said a few words about East-West unity and made a point of hugging the recipient, Death Row artist Snoop Doggy Dogg.

Nonetheless, Suge’s words spread like flu germs, reigniting ancient East-West hostilities. It was in this increasingly tense atmosphere that Big and the Junior M.A.F.I.A. clique reached Atlanta for Jermaine Dupri’s birthday party last September. During the after-party at a club called Platinum House, Suge Knight’s close friend Jake Robles was shot. He died at the hospital a week later. Published reports said that some witnesses claimed a member of Puffy’s entourage was responsible.

At the mention of the incident, Puffy sucks his teeth in frustration. “Here’s what happened,” he says. “I went to Atlanta with my son. At that time, there wasn’t really no drama. I didn’t even have bodyguards, so that’s a lie that I did. I left the club, and I’m waiting for my limo, talking to girls. I don’t see [Suge] go into the club; we don’t make any contact or nothing like that. He gets into a beef in the club with some niggas. I knew the majority of the club, but I don’t know who he got into the beef with, what it was over, or nothing like that. All I heard is that he took beef at the bar. I see people coming out. I see a lot of people that I know, I see him, and I see everybody yelling and screaming and shit. I get out the limo and I go to him like, ‘What’s up, you all right?’ I’m trying to see if I can help him. That’s my muthafuckin’ problem, Puffy says, pounding his fist into his palm in frustration. “I’m always trying to see if I can help somebody.

“Anyways, I get out facing him, and I’m like, ‘What’s going on, what’s he problem?’ Then I hear shtos ringing out, and we turn around and someone’s standing right behind me. His man—God bless the dead—gets shot, and he’s on the floor. My back was turned; I could’ve got shot, and he could’ve got shot. But right then he was, like, ‘I think you had something to do with this.’ I’m, like, ‘What are you talking about? I was standing right here with you!’ I really felt sorry for him, the the sense that if he felt that way, he was showing me his insecurity.”

After the Atlanta shooting, people on both coasts began speculating. Would there be retribution? All-out war? According to a New York Times Magazine cover story, Puffy sent Louis Farrakhan’s son, Mustafa, to talk with Suge. Puffy says he did not send Mustafa but did tell him, “If there’s anything you can do to put an end to this bullshit, I’m with it.” The Times reported that Suge refused to meet with Mustafa. Suge has since declined to speak about his friend’s murder.

Less than two weeks later, when it came time for the “How Can I Be Down?” rap conference in Miami, the heat was on. Suge, who has never concealed his past affiliations with L.A’s notorious Bloods, was rumored to be coming with an army. Puffy was said to be bringing a massive of New York drug lords and thugs. When the conference came and Puffy did not attend, Billboard reported that it was due to threats from Death Row.

`On December 16, 1995, it became apparent that the trouble was spilling into the streets. In Red Hook, Brooklyn, shots were fired at the trailer where Death Row artist Tha Dogg Pound were making a video for “New York, New York”—which features Godzilla-size West Coasters stomping on the Big Apple. No one was hurt, but the message was clear. Then came “LA, La,” an answer record from New York MC’s Tragedy, Capone, Noreaga, and Mobb Deep. That video featured stand-ins for Tha Dogg Pound’s Daz and Kurupt being kidnapped, tortured, and tossed off the 59th Street Bridge.

By this time, the rumor mill had kicked into overdrive. The latest story was that Tupac was boning Biggie’s wife, Faith Evans, and Suge was getting with Puffy’s ex, Misa Hylton. Death Row allegedly printed up a magazine ad featuring Misa and Suge holding Puffy’s two-year-old son, with a caption reading “The East Coast can’t even take care of their own.” The ad—which was discussed on New York’s Hot 97 by resident gossip Wendy Williams—never ran anywhere, but reps were tarnished nonetheless. Death Row now denies that such an ad ever existed. Puffy says he didn’t know about any ad. Misa says, “I don’t do interviews.”

Meanwhile, Tupac kept rumors about himself and Faith alive with vague comments in interviews like “You know I don’t kiss and tell.” But in “Hit Em Up,” released this May, he does just that, telling Biggie, “You claim to be a player, but I fucked your wife.” (Faith, for her part, denies ever sleeping with Tupac.)

When talk turns to his estranged wife, Biggie shrugs his shoulders and pulls on a blunt. “if the muthafucka really did fuck Fay, that’s foul how he’s just blowin’ her like that,” he says. “Never once did he say that Fay did some foul shit to him. If honey was to give you that pussy, why would you disrespect her like that? If you had beef with me, you’re like, ‘Boom, I’ma fuck his wife,’ would you be so harsh on her? Like you got beef with her? That shit doesn’t make sense. That’s why I don’t believe it.”

What was still mostly talk and propaganda took a turn for the ugly at the Soul Train Awards this past March. When Biggie accepted his award and bigged-up Brooklyn, the crowd hissed. But the real drama came after the show, when Tupac and Biggie came face-to-face for the first time since Pac’s shooting more than two years before. “That was the first time I really looked into his face,” says Big. “I looked into his eyes and I was like, Yo, this nigga is really buggin’ the fuck out.”

The following week’s Hollywood Reporter quoted an unnamed source saying that Shakur waved a pistol at Biggie. “Nah, Pac didn’t pull steel on me,” says Big. “He was on some tough shit, though. I can’t knock them dudes for the way they go about their biz. They made everything seem so dramatic. I felt the darkness when he rolled up that night. Duke came out the window fatigued out, screaming ‘West Side! Outlaws!’ I was, like, ‘That’s Bishop [Tupac’s character in the movie Juice]!’ Whatever he’s doing right now, that’s the role he’s playing. He played that shit to a tee. He had his little goons with him, and Suge was with him and they was like, li, ‘We gonna settle this now.’”

That’s when Big’s ace, Little Caesar of Junior M.A.F.I.A., stepped up. “The nigga Ceez—pissy drunk—is up in the joint, like, ‘Fuck you!’” Big recalls. “Ceez is, like, ‘Fuck you, nigga! East Coast, muthafucka!’ Pac is, like, ‘We on the West Side now, we gonna handle this shit.’ Then his niggas start formulating and my niggas start formulating—somebody pulled a gun, muthafuckas start screaming, ‘He got a gun, he got a gun!’ We’re, like, ‘We’re in L.A. What the fuck are we supposed to do, shoot out?’ That’s when I knew it was on.”

But not long after the Soul Train incident, it appeared as if Death Row might be starting to chill. At a mid-May East-West “rap summit” in Philadelphia, set up by Dr. Ben Chavis to help defuse the situation, Suge avoided any negative comments about Puffy (who did not attend because he says there was too much hype around the event). “There’s nothing between Death Row and Bad Boy, or me and Puffy,” said Knight. “Death Row sells volume—so how could Puffy be a threat to me, or Bad Boy be a threat to Death Row?” A few weeks later, however, Death Row released a song that told a different tale.

When Tupac’s “Hit ‘Em Up”—which mimics the chorus of Junior M.A.F.I.A.’s Player’s Anthem” (“Grab your Glocks when you see Tupac”)—hit the streets of New York, damn near every jeep, coupe, and Walkman was pumping it. No fakin’ jacks here, son; Tupac set it on the East something lovely. He says he put out the song in relation for Big’s 1995 “Who Shot Ya,” which he took as a comment on his own shooting. “Even if that song ain’t about me,” he told VIBE, “You should be, like, ‘I’m not putting it out, ‘cause he might think it’s about him.’”

“I wrote that muthafuckin’ song way before Tupac got shot,” says Big, like he’s said it before. “It was supposed to be the intro to that shit Keith Murray was doing on Mary J. Blige’s joint. But Puff said it was too hard.”

As if the lyrical haymakers thrown at Bad Boy weren’t enough, Pac went the extra mile and pulled Mobb Deep into the mix, “Don’t one of you niggas got sick-cell or something?” he says on the record. “You gonna fuck around and have a seizure or a heart attack. You’d better back the fuck up before you get smacked the fuck up.”

Prodigy of Mobb Deep says he couldn’t believe what he heard. “I was, like, Oh Shit. Them niggas is shittin’ on me. He’s talking about my health. Yo, he doesn’t even know me, to be talking about shit like that. I never had any beef with Tupac. I never said his name. So that shit just hurt. I’m, like, Yeah, all right, whatever. I just gotta handle that shit.” Asked what he means by “handling” it, Prodigy replies, “I don’t know, son. We gonna see that nigga somewhere and—whatever. I don’t know what it’s gonna be.” In the meantime, the infamous ones plan to include an anwer to “Hit ‘Em Up” on the B-side of an upcoming single.

In a recent interview with VIBE online, Tupac summed up his feelings toward Bad Boy in typically dramatic fashion: “Fear got stronger than love, and niggas did things they weren’t supposed to do. They know in their hearts—that’s why they’re in hell now. They can’t sleep. That’s why they’re telling all the reporters and all the people, ‘Why they doing this? They fucking up hip hop’ and blah-blah-blah,’ cause they in hell.

They can’t make money, they can’t go anywhere. They can’t look at themselves, ‘cause they know the prodigal son has returned.”

In the face of all this, one might wonder why Biggie hasn’t retaliated physically to Tupac’s threats. After all, he’s the same Bedstuy soldier who rapped, “C-4 to your door, no beef no more.” Says Big, “The whole reason I was being cool from Day One was because of that nigga Puff. ‘Cause Puff don’t get down like that.”

So what about a response on record? “He got the streets riled up because he got a little song dissing me,” Big replies, “but how would I look dissing him back? My niggas is, like, ‘Fuck dat nigga, that nigga’s so much on your dick, it don’t even make no sense to say anything.”

Given Death Row’s intimidating reputation, does Puffy believe that he’s in physical danger? “I never knew of my life being in danger,” he says calmly. “I’m not saying that I’m ignorant to the rumors. But if you got a problem and somebody wants to get your ass, they don’t talk about it. What it’s been right now is a lot of moviemaking and a lot of entertainment drama. Bad boys move in silence. If somebody wants to get your ass, you’re gonna wake up in heaven. There ain’t no record gonna be made about it. It ain’t gonna be no interviews; it’s gonna be straight-up ‘Oh shit, where am I? What are these wings on my back? Your name is Jesus Christ?’ When you’re involved in some real shit, it’s gonna be some real shit.

But ain’t no man gonna make me act a way that I don’t want to act. Or make me be something I’m not. I ain’t a gangster, so why y’all gonna tell me to start acting like a gangster? I’m trying to be an intelligent black man. I don’t give a fuck if you niggas think that’s corny or not. If anybody comes and touches me, I’m going to defend myself. But I’ma be me—a young nigga who came up making music, trying to put niggas on, handle his business, and make some history.”