‘Everything Was Our Playground’: ‘Poor Things’ Crew Talk Creating Surrealist Fairy Tale

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

When production designers Shona Heath and James Price were tasked with designing the dark comedy Poor Things, Yorgos Lanthimos’ Oscar-nominated movie about a woman whose resurrected with her infant’s brain, they had several key decisions to make. For starters, how would they represent the London mansion, which included the laboratory of mad scientist Dr. Baxter, played by Willem Dafoe? The answer turned out to be simple: They’d put human anatomy along the walls and ceiling.

They stapled packing foam to the atrium ceiling to resemble the “wiggly bits on the roof of your mouth,” Heath says. They plastered interlocking ears to the living room, and added wormhole-like structures to the walls that looked like a brain cross section. Inspired by English architect John Soane’s wall ornamentation, Heath says the human attributes revealed how the home “lived and breathed and loved and heard.”

More from Rolling Stone

“It was not easy to get it right,” Heath tells Rolling Stone, “[but] it wasn’t difficult because everything was our playground, we could go anywhere.”

This marked one of dozens of choices Heath, Price, and costume designer Holly Waddington made to transform the sharp satire into a visually arresting, surrealist fairy tale. In the film, a Frankenstein-like Bella Baxter (Emma Stone) undergoes a sexual awakening spanning several mythical cities with debauched lawyer Duncan (Mark Ruffalo). The film teeters between cruelty and comedy as Bella spends most scenes having loads of sex. To Rolling Stone’s David Fear, the film “revels in the notion that experience and enlightenment are conjoined twins.” The film is up for 11 Oscars — including costume and production design — so Rolling Stone spoke with the crew to find out what it was like to design such an imaginative, sexed-up fairytale.

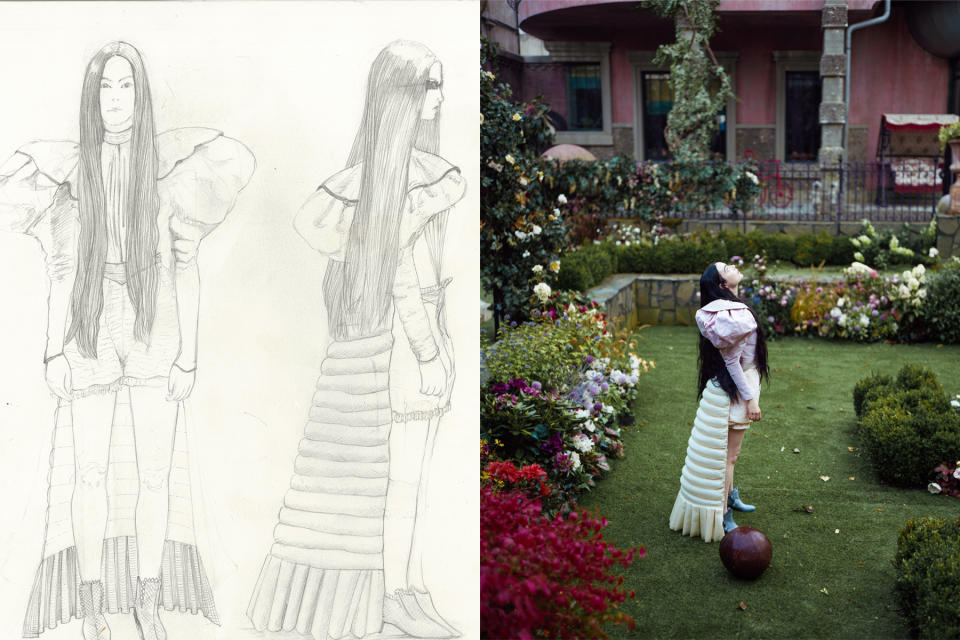

The surrealist film draws inspiration from Alasdair Gray’s novel of the same name, set in the late nineteenth century, combining gothic horror, science fiction, and satire. When designing balloon sleeves and ruffled collars for Bella, costume designer Holly Waddington drew on the 1960s space-age fashion of Paco Rabanne, Pierre Cardin, and André Courrèges, while Bella’s white Victorian boots featured a toe cutout partially inspired by Courrèges futuristic aesthetic.

When Bella is introduced to Dr. Baxter’s assistant Max (Ramy Youssef) for the first time, she wears a lobster tail-like undergarment outside her clothes, a late Victorian piece that adds volume underneath a skirt. Lanthimos resisted dressing the protagonist as an adult in baby clothes, Waddington says. Instead, Bella waddles around her London home thrashing, blabbing, and twirling in elaborate blouses. From the waist down, the protagonist is barefoot and nearly naked. Massive hoop skirts get in the way of play, Waddington says, “that’s why we see her in her knickers a lot.”

Bella’s clothing was purposefully incongruous with her mental state and body, Waddington adds. “Mrs. Prim [Vicki Pepperdine], the housemate, dressed her in the morning, probably put her in the full costume, the pants, the underskirt, the bodice and maybe by mid morning, she just got rid of it because she’s playing on her tricycle and she’s feeding animals in the garden,” Waddington says. “Everything was character led.”

The men — including Duncan, who seduces Bella into a sexfest abroad — are often dressed in three-piece suits, top hats, and erect collars, Waddington says, to reflect “the cartoons of men” who made up the ruling class. Though the protagonist tows the line between infancy and adulthood, Waddington says she didn’t worry about sexualizing the lead.

“She has just appeared in the world in the body of, let’s say, a 30-year-old woman but with the mind of an infant, so everybody else is a victim of that culture and that brainwashing,” Waddington says.

Waddington usually works on projects where logic supersedes wonder, ultimately leading to more boring results, she says. In Poor Things, the costume designer felt encouraged to forget about Bella’s age as she traveled to Lisbon, Alexandria, Paris, and back to London. They spoke less about whether the actions were appropriate, and more about the easiest way to take her clothes off – and on again.

“When she goes to Lisbon, it’s a different look,” Waddington says. “It’s a different material quality and fabrics. So, I probably wasn’t thinking about age of consent or anything as practical or real as that but I was thinking, ‘Okay, she’s no longer in that stage of [a] very young child. She’s having sex and she’s speaking a bit more clearly.’”

As production designers Price and Heath created Bella’s first stop on her journey, Lisbon, it was important to tune out of reality. Built in Budapest, home to the largest soundstage in continental Europe, the fictionalized capital of Portugal took about 20 weeks to build, looking to Ricardo Bofill’s Brutalist architecture to arrive at a slightly unusual city. Lisbon included three- and four-story structures, streets made from undulating steel decks, and a 170-foot scenic backdrop.

“This is the first time she’s out in the world experiencing alcohol and sex and nice-tasting oysters and Portuguese tarts, so it’s got a psychedelic feel, a yellow brick road field to it,” Price tells Rolling Stone.

Unlike the other life-size sets, the cruise liner that Bella and Duncan travel on after Lisbon is a miniature that stretches about six feet long. It includes two decks along with internal lights and smoke billowing from the ship’s funnel. A curved LED screen mimicked the deep blue sea and sky.

The next stop, the slums of Alexandria, were built on a 30-foot wide structure influenced by the ivory towers found in Massimo Listri’s Cabinet of Curiosities. Heath says they used a burnt-orange hue to communicate the “suffocating heat” within the poverty stricken city, juxtaposing the luxurious cruise ship. They also drew inspiration from Dutch painter Hieronymus Bosch’s work that often depicted sin and nightmarish moral failures.

“We refer back to the beginning of Dracula quite a bit for that, there was a battle sequence which is shot against a red sky,” Price says. “We weren’t as stylized as that in the end, but that’s the way we approached it.”

When designing the Parisian brothels, Heath and Price opted for cool blues and ultraviolet tones, pulling from paintings by French artists Luigi Loir and Edgar Degas.

“We really wanted to avoid those colors that are represented as sins of the flesh, red and pink,” Heath says. “We wanted to go completely opposite, a bit colder like the weather and snow.”

The brothel’s interior included light-up floors, whereas the exterior included penis-shaped windows and massive carvings of nude women, Heath adds. While such graphic symbols would perplex a regular visitor, to Bella it was another part of the human anatomy.

“She would have looked at that as if, ‘Oh, there’s a nice building with things on [it].’” Heath says. “She knows what they are. She doesn’t know what that means, why it would mean something that we think is bad, to her it was body parts.”

The clothing styles within the brothel carried similar themes of sexual expression. You’ll never find Bella in a corset, nor any of the other sex workers in the Parisian brothel. Instead they’re dressed in clothing with skin-tone hues that accentuate the female frame, Waddington expresses.

“They have these big jackets that were made — some of them to the waist, some of them to the ground that had cut outs for their breasts to be on show — and I wanted to feel like it was a celebration of the body, of the skin, of the flesh, of their shapes,” Waddington adds.

Bella’s wedding dress, influenced by French designer Madeleine Vionnet (who pioneered the bias-cut dress), honors her figure in that way, too. The bubble mesh shoulder pads wrapped with bands symbolized dominance despite its light, airy fabric, Waddington says.

“The sort of imprisonment or the cage is literally made of nothing; it’s just a bit of tissue, it’s a bit of net,” Waddington says. “So, it’s almost as if she’s untrappable.”

Waddington, who has worked on period dramas like Hulu’s The Great and Altitude Films’ Lady Macbeth, says that working with the Oscar-nominated director Lanthimos is like walking a tightrope. With no boundaries around timeframes, style, and architectural design, Lanthimos steered the surrealist ship, ultimately helping Waddington, Heath, and Price land their first Oscar nomination.

“One of the great things about working with Yorgos is that – it’s what kind of makes it a bit unnerving as well and a bit daunting – is that you don’t really know if you’re doing it right,” Waddington says. “You don’t feel very safe doing a film with him, it’s like, ‘Oh, God, hope this is gonna work.’ You’re working very instinctively, and working very hard.”

Best of Rolling Stone