Every Radiohead Album Ranked From Worst to Best

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

The post Every Radiohead Album Ranked From Worst to Best appeared first on Consequence.

Welcome to our definitive ranking of every Radiohead album from worst to best. We originally published this list in June 2017 and will keep adding to it as long as Radiohead keeps adding to their discography. So, get ready to agree, disagree, and agree to disagree… still, we’re pretty sure everything is in its right place.

The songs had almost all been written, the studio had been booked, and EMI, anticipating an easy process, set a release date only a few months away. “Every three or four days, the record company or manager would turn up to hear these hit singles,” recalled producer John Leckie, “And all we’d done was get a drum sound or something.” Weeks passed. “There was a lot of ‘Jonny’s got to have a special sound…’ We spent days hiring in different amplifiers and weird guitars for him. In the end, he used what he’d been using for the last couple of years.” Thom Yorke called it “painful self-analysis, a total fucking meltdown.” The band missed its deadline by almost six months.

If the recording process for Radiohead’s second album, The Bends, sounds torturous, it also sounds like how they recorded most of their other albums. The band had to take a break in the middle of the frustrating OK Computer sessions. Kid A spanned 18 months and half a dozen different studios. In Rainbows took two and a half years.

Looking back at The Bends, it’s easy to see the blueprint for Radiohead’s later, wilder sounds — how a band dubbed “Nirvana-lite” became a genre unto itself. There’s the glacial, perfectionist pace; self-analysis and self-doubt; the feeling of boredom with older sounds; and anxiety about finding something new. For the most part, they have: they’ve put out nine studio albums, most of which really do sound distinct from all the others.

Because of this, their technical wizardry, their fire-breathing live shows, and their timeless gift for melody, Radiohead are the most beloved, critically acclaimed rock band working today. All nine records range from “possibly the greatest album of all time” to, at the very least, “pretty good.” This made ranking them a difficult, vexing process. We didn’t rest until we compromised on a list that left us all equally upset.

Without further ado: Radiohead, Ranked and Dissected. Knives out for the letdown, I’m optimistic, but I might be wrong, there, there, no surprises, it’s just lucky everything’s in its right place.

— Wren Graves

09. Pablo Honey (1994)

Runtime: 42:11, 12 tracks

“There are many things to talk about” (Central Theme): While so much of Radiohead’s future work would revolve around a Big Idea, whether it be musically or lyrically, the only glue that holds Pablo Honey together is the gnarled angst that was so prevalent on rock albums in the ’90s. That wasn’t an intentional choice, per se; it’s just where the band was at in their lives (remember, Thom Yorke was in his early 20s when he wrote the lyrics). The nature, paranoia, and dystopian landscapes would come later. But for now, they were seen as England’s answer to grunge.

“Siren singing you to shipwreck” (Squint and It’s a Pop Song): More straightforward than anything that came later, Pablo Honey comes loaded with plenty of radio-ready material, generic as it often is. “Creep” is the obvious big hit, but “How Do You?” could have easily held its own on the Top 40. Almost pop-punk in its bounce, it gets even peppier (and more chaotic) during its final moments with some tack piano from Jonny Greenwood.

“It wears her out, it wears her out” (Sneakiest Dance Song): The jazzy hiss of closer “Blow Out” makes for apathetic swaying on the verses before the chorus propels clubgoers into unhinged flailing. Granted, the loud-soft dynamics can be jarring, but whoever said dancing had to be pretty?

“Anyone can play guitar” (Essential Instrument or Sound): Outside of some scattered tape loops, Pablo Honey has the most conventional instrumentation of any Radiohead release. So it’s no surprise (ba-dum-ching!) that the most memorable instrument is, well, a guitar. That would be Greenwood’s dead chords on “Creep,” which he played at the end of each verse to ruin the otherwise quiet song. It’s no secret that the band loved his act of sabotage, thus predicting their eventual love of jolting left turns in their music.

“For a minute there, I lost myself” (Most Adventurous Shift in Time Signature): Only three songs break out of 4/4 time (still significant for no-frills alt-rock), with the band taking the biggest leap on the verses of “Ripchord,” which move from 4/4 to 2/4 whenever the distortion kicks in.

“Living on Animal Farm” (Literary/Pop-Culture Allusions): More of a tribute than a direct homage, “Stop Whispering” was written to honor the Pixies, so much so that the single’s art uses the same square framing on a white background as Surfer Rosa.

“Out of control on videotape” (Most Notable Music Video): “Creep” is a standard performance video of the era, but “Stop Whispering,” while not as narratively satisfying as something like “Knives Out,” still features a litany of the vaguely post-apocalyptic imagery the band would perfect down the line: a rusted-over wasteland, an antiquated diving suit, bees swarming over everything, the works.

“Get judged” (Verdict): As an alt-rock time capsule, Pablo Honey is solid, and had it been Radiohead’s only release, or even if the band had stuck to its drums-and-guitars formula for the rest of their career, we might even call it great. But when you listen to what came after it, the record just feels a little thin, a little one-note, a little laughable in its first-person melodrama. It’s not bad — it’s just not very interesting.

— Dan Caffrey

08. The King of Limbs (2011)

Runtime: 37:34, 8 tracks

“There are many things to talk about”: Full of electronic chirps, bubbling keyboards, and songs named after flowers and birds, The King of Limbs is Radiohead’s attempt to find man’s place in nature. Of course, that leads to ugliness — the wild humans of “Feral” seem to be Holocaust-era Nazis, although Yorke’s voice is so distorted that it’s hard to pick up on without reading the lyric book. Still, the songs themselves are unrelentingly gorgeous.

“Siren singing you to shipwreck”: Once you get past the menacing bass, hungry synths, and twisted pretzel percussion of “Lotus Flower,” there’s a rather sweet melody sung in Yorke’s most angelic falsetto. There’s also not one, but two hooks! Max Martin would be proud. “There’s an empty space in side of my heart/ Where the weeds take root,” Yorke sings on the first and later: “Cause all I want is the moon upon a stick/ Just to see what if/ Just to see what is.” Like an opiate dream, “Lotus Flower” is an enchanting ride with darkness lapping at the edges.

“It wears her out, it wears her out”: His ability to funk up rock songs with dance beats makes Phil Selway the most under-appreciated member of Radiohead, and I will fight anyone who says otherwise with a drumstick. On “Morning Mr. Magpie,” he carefully syncopates a few strikes of the snare so that the rhythm section is always leaning into the beat. This also prompts the guitar strings to stay so palm-muted that they’re almost another percussive instrument. True story: While I was sitting at my computer, my fiancée pulled my earbuds out to make fun of me for wiggling my butt.

“Anyone can play guitar”: The piano riff that opens “Bloom” doesn’t so much kick off the album as sidle up to it from behind. First, there’s the modest amplification, so quiet you’re reaching for the volume as soon as you’ve pressed play. No sooner does it establish itself as a lovely, if un-Radiohead-like little snatch of melody before it’s gone, transformed into a bit of background burbling. The mood for the album is now set: No grand gestures or towering statements this time around, just a quiet beauty that inevitably fades away.

“For a minute there, I lost myself”: Near the end of “Codex,” around the 3:34 mark, Radiohead relaxes from 4/4 time to 5/4 time and then repeats for four gentle measures. This allows the piano to linger and the synth to warble on unconstrained. The song features a character sitting by the lake and thinking; within this context, the two extra beats per measure feel almost accidental — like he’s unsure of himself and following a thought or maybe just (literally) losing track of time.

“Living on Animal Farm“: On “Codex,” the lyrics “Just dragonflies/ Fly to the sun/ No one gets hurt,” reference the Greek myth of Icarus. He and his father Daedalus attempted to escape from Crete on wax wings, and before they departed, Daedalus warned his son of complacency and hubris — neither to fly too low because the sea’s dampness could clog his wings, nor too high because the sun would melt them.

But Icarus is too proud, he flies too high, his wings are melted, he falls, and he dies. Despite the direct reference to the tragedy, Radiohead’s lyrics often traffic in ambiguity, and “Codex” is no exception; it’s a description of anything from a sunny afternoon at the lake to a suicide. The literary allusion would seem to suggest that whoever this character at the lake is, one thing they’re not feeling is proud.

“Out of control on videotape”: The King of Limbs: Live from the Basement video is quite good, but this category has one clear winner: the dance that launched a thousand gifs, the video that birthed a million memes — ladies and gentleman, “Lotus Flower!”

With a style that can only be described as “accidentally touching an electric fence,” this video features not only Yorke’s trademark gyrating, but also long, cockeyed stares into the camera and an extended sequence where he fondles his own chest. It’s unapologetically goofy while still coming across as totally sincere. It’s also a testament to Yorke’s charisma. How many rock stars could have pulled this off?

“Get judged”: The King of Limbs is original, coherent, and quite lovely to listen to, but that’s true of almost every Radiohead album, and most of the others have the advantage of at least one tentpole single strong enough to open or close a music festival. To be fair, that wasn’t what the band was aiming for here, but I’d be willing to bet that no Radiohead fan’s favorite song is on TKOL — even Pablo Honey has “Creep.” Albums like Kid A or OK Computer contain all the spectacle of an exploding volcano while TKOL, at a brisk 37 minutes, is more like a long walk down a forest path. It’s a wonderful way to pass the time, but the memory is going to fade.

— W.G.

07. Amnesiac (2001)

Runtime: 43:57, 11 tracks

“There are many things to talk about”: On a surface level, Amnesiac is about the main word in its title: amnesia or chronic forgetfulness or, if we’re speaking in the terms of Radiohead’s frequent sci-fi obsessions, a memory wipe. But Yorke elevates the potentially singular lyrical content by bringing the words to a more spiritual yet still scientific place. Taking a note from the agnostics’ belief that, to be reincarnated, one has to forget who they were in their past life, he’s able to move through a variety of eras (ancient Greece, ancient Egypt, today), philosophies (Buddhism, cyclical time), and musical genres (jazz, blues, krautrock).

“Siren singing you to shipwreck”: Since its cells are constantly mutating, Amnesiac often does away with traditional song structure in favor of free jazz, loops, and electronica, all delivered in short bursts so the band can clear the path for the next thing. That all changes during “Knives Out.” Placed smack-dab in the middle of the album, it’s as if Radiohead slams on the brakes in the middle of a time leap, bringing everything back to a more tempered speed and arrangement. The conventional art-rock is pretty catchy, too, despite being about cannibalism.

“It wears her out, it wears her out”: Truth be told, I can’t picture dancing to anything on Amnesiac, at least not in the casual club sense. I guess a lot of the songs would fit in at an interpretive dance performance at the MOMA or something, and closer “Life in a Glass House” — backed by the Humphrey Littleton Band — is modeled after a New Orleans jazz funeral. People dance at those, right?

“Anyone can play guitar”: The Mingus-summoning “Pyramid Song” always gets praised for its ascending piano scale, but it’s the uneasy string section that truly brings out the mystery and wonder in Yorke’s lyrics about the Egyptian underworld.

“For a minute there, I lost myself”: Get this — there are actually no time-signature shifts on Amnesiac. Every song is in 4/4, proving that the wildness comes from changes in tonality and instrumentation, not the beat.

“Living on Animal Farm“: We already talked about Charles Mingus and the realm of the dead, both of which represent the two halves of Amnesiac’s cultural influences: other musicians and philosophy/spirituality. While there aren’t as many direct references to science fiction and George Orwell novels, as is the case with past and future Radiohead releases, the band has cited various subtle nods to the theories of Stephen Hawking (“Pyramid Song,” again), The Smiths (“Knives Out”), and even themselves (an alternate, bicycle dirge version of “Morning Bell”).

“Out of control on videotape”: Even before I was a Radiohead fan, Michel Gondry’s single-shot video for “Knives Out” stuck with me for its surreal depiction of domestic claustrophobia. Sometimes you’re deathly worried about your partner (Yorke watching her become a life-sized Operation game), and sometimes you’re aggravated by them (the two beating each other with toy weapons inside a TV screen), neither of which is a pleasant feeling.

“Get judged”: Because it came out of the same sessions as Kid A, Amnesiac tends to sound detached. That, combined with its refusal to stay in one place, can make it hard to penetrate upon relistening. But once you view it in the proper thematic context, it becomes a bizarre kind of masterpiece. The band isn’t jumping from older art forms like blues and jazz to chilly electronic effects because they want to jostle the listener — they’re doing it to suit the time- and dimension-traveling nature of Yorke’s lyrics. Or is it the other way around?

— D.C.

06. Hail to the Thief (2003)

Runtime: 56:35, 14 tracks

“There are many things to talk about”: In case you didn’t pick up on it from the album title, Hail to the Thief ruminates on soiled government, false patriotism, and blind faith. Right from opener “2+2=5,” the album wastes no time hounding on the intense politics of the new millennium. Yorke often sings about interpretations of the War on Terror and the rise of Republican politics in America, and the album’s infamous leak 10 weeks before its release unintentionally emphasized these core themes. If you can’t trust the government and the ways in which it runs things online or offline, then why not claim independence? Hail to the Thief was legally Radiohead’s final album with Parlophone. With the contract wrapped up, they were free to go their own way shortly after.

“Siren singing you to shipwreck”: Leave it to Radiohead to double Hail to the Thief’s most frightening track as its most pop-like, too. Colin Greenwood’s bass on “Myxomatosis. (Judge, Jury & Executioner.)” sounds filtered through an outdated fuzz pedal while a detuned keyboard mimics ‘70s new wave. Despite the harsh sonics, the song still runs according to a pop setup, clearing the air for a quiet chorus where Selway’s drums ditch the downbeat to muddle preconceived notions of pop. But at its core, “Myxomatosis” remains a radio-friendly recording.

“It wears her out, wears her out”: Despite its slow pace and almost nonexistent bassline, “Backdrifts. (Honeymoon Is Over.)” is the album’s most do-as-you-please groove, complete with an extended outro. Actually, maybe that’s what makes it work so well. Yorke backs out of the spotlight to let drum machines and modular synthesizer wiggle over one another like visible sine waves. Get lost in it the way the band members do, whether you’re executing interpretive dance moves at a club in Berlin or cutting up the carpet of your own bedroom.

“Anyone can play guitar”: Hail to the Thief is not an alt-rock record. It’s not an electronic album. It’s no college rock LP either. Instead, the band finds middle ground between the three, which makes Hail to the Thief both their most experimental record as well as one of their most accessible. For the former trait, they frequently rely on laptops, such as the ones on “Where I End and You Begin. (The Sky Is Falling In.)”. Without the computers, the otherwise straightforward indie rock song would lose its hums and ringing, the cloud of mist that lifts everything to the next level.

“For a minute there, I lost myself”: Perhaps the easiest introduction to Hail to the Thief is the album’s biggest flip in pace. “We Suck Young Blood. (Your Time Is Up.)” stands on a slurring drawl of a tempo, oozing long guitar and brooding handclaps while heavy piano notes trudge at its center. But then, as if woken up from a night terror, things triple in time. The piano becomes a beautiful melody, the drums slip into jazz territory, and a shrill guitar line quivers in fear. Then it fades. Everything goes back to normal, the heartbeat slows, and their eerie harmonies stretch out over the solemn ivories, petting your head until you forget the jump even happened. It’s as bold as the vampiric imagery the song draws upon throughout.

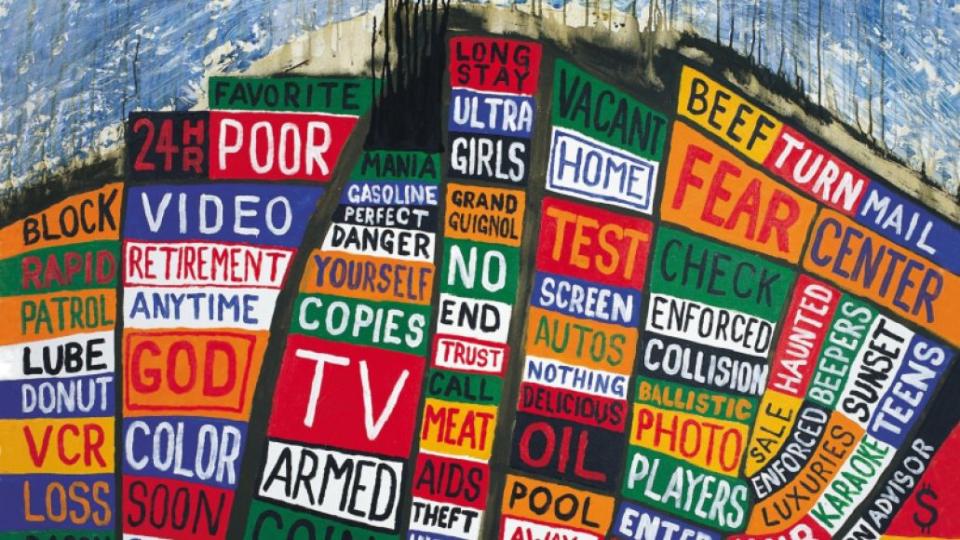

“Living on Animal Farm“: Hail to the Thief begins with its most obvious literary allusion, “2+2=5 (The Lukewarm.)”, where the brainwashing doublethink of George Orwell’s 1984 sounds both passionate and claustrophobic. “Are you such a dreamer to put the world to rights/ I’ll stay home forever where two and two always makes a five,” Yorke sings. “Don’t question my authority or put me in the box ’cause I’m not.” As the album’s third and final single, “2+2=5” can’t leave the listener with only one reference.

Subtitle “The Lukewarm” is a nod to Dante’s writings (those who are lukewarm “don’t give a fuck” about living on the edge of Inferno), the album name-drop scolds the president (and mocks anyone who watched George W. Bush with heart-shaped eyes), and there’s some extra math love thanks to titular text-painting (“two and two” is sung on an ascending 4th while “always makes” is sung on an ascending 5th). In a single song, Radiohead satisfies not just lit nerds, but politic junkies and math geeks, too.

“Out of control on videotape”: “There There. (The Boney King of Nowhere.)” is classic Radiohead. With some literal text-to-image translations (“In pitch dark I go walking in your landscape/ Broken branches trip me as I speak”) and personified animals, the stop-motion animation video is easy to follow along. Its real feat, however, is how the imagery enhances the song’s takeaway quote: “Just ’cause you feel it doesn’t mean it’s there.”

If you remember the video well, thank the band’s tongue-in-cheek promotion. It played hourly on both MTV2 and the Times Square Jumbotron the day of its debut in 2003. As a bonus, their critique of mass-media culture and digital consumption was enhanced by the creation of radiohead.tv, a website where short films, music videos, and live webcasts were streamed at scheduled times, including this very music video.

“Get judged”: There’s no pretending Hail to the Thief’s 15-song tracklist doesn’t frighten listeners, casual or not. Even the band members themselves have admitted that. Yet its 56-minute runtime also allows the album to be rich with production, time signatures, and intellectual perfections. Slight electronic vocal distortion washes over Yorke’s voice on “Sit Down. Stand Up. (Snakes & Ladders.)” acts as a subtle hint at what’s to come: manic repetition and a cocaine-laced bassline where the rain, finally, drops. This is the type of rawness bands dream of creating. There are ties to their other records, too.

“Go to Sleep. (Little Man Being Erased.)” sounds like a B-side from The Bends due to its acoustic guitar overlay. “A Wolf at the Door. (It Girl. Rag Doll.)” is a Grimms’ fairytale ballad off Amnesiac. “Sail to the Moon. (Brush the Cobwebs Out of the Sky.)” was, at the time, a look at what was to come with In Rainbows. Like Stanley Donwood’s cover art — a collection of phrases drawn from roadside advertising in Los Angeles — Hail to the Thief is a pop record sparkling with twisted fears, electronic sampling, and satirical lyrics that bite. Years later, it still feels like it’s a genius moment somehow, as if by magic, captured on tape, where unbridled energy overrides the album’s daunting length.

— Nina Corcoran

05. A Moon Shaped Pool (2016)

Runtime: 52:31, 11 tracks

“There are many things to talk about”: We’re still combing over the lyrics, but as many critics have pointed out, there’s a focus on orchestration (usually from the London Contemporary Orchestra) that’s unprecedented in the band’s catalog. Even though they’ve been turning to string arrangements and the like as far back as The Bends, the classicism has always been more of a flourish or trick rather than a sonic backbone. In that way, A Moon Shaped Pool‘s closest blood relative is “Spectre,” seemingly more concerned with aural majesty — older songs stirred and reshaped in the same lunar-cast tide pool — than any kind of lyrically unified theme.

“Siren singing you to shipwreck”: Listen to it enough and the miniature piano sonata of “Daydreaming” becomes less of a sonata and more of a Top 40 ballad. And if its stalled vocal transmissions were ever allowed to reach the end of their phrases, it might even transform the song into a more danceable Top 40 banger. But the bombast never comes and we’re left with just the animalistic grunts of cellos, making “Daydreaming” an exercise in catchiness, creepiness, and restraint.

“It wears her out, it wears here out”: Like “Talk Show Host” before it, “The Numbers” flirts with trip hop, but it’s “Ful Stop” that really greases up the dance floor. The song’s progression recreates the sensation of emerging from a nightclub bathroom at the witching hour, the percussion and bass drone becoming clearer and louder as you move closer to the crowd.

“Anyone can play guitar”: Since A Moon Shaped Pool is purposely not driven by guitar, it ends up being the six-string that stands out, specifically the bare-bones acoustic strumming on “Desert Island Disk.”

“Living on Animal Farm”: As previously stated, we’re still working our way through everything, but here’s what we’ve caught so far: the World War II propaganda and familiar use of nursery rhymes on “Burn the Witch” (the title could also allude to the Queens of the Stone Age song of the same name, but probably not); the common music-criticism question that forms the title of “Desert Island Disk”; another nursery-rhyme motif in the title and lyrics of “Tinker Tailor Soldier Sailor Rich Man Poor Man Beggar Man Thief” (also referenced by Tom Waits in “Heartattack and Vine”); the spy novel and film adaptation that also use “Tinker Tailor…” as their namesake; and an allusion to Jesus Christ’s practice of foot-washing on “True Love Waits.”

“Out of control on videotape”: We kindly refer you to the video of “Burn the Witch” and animator Virpi Kettu’s subsequent explanation of it.

“Get judged”: As time has gone on, Yorke and co. have become increasingly less interested in conveying their messages through words, and while the lyrics of A Moon Shaped Pool aren’t as distorted or indecipherable as Kid A or Amnesiac, they’re purposely overshadowed by the musical lushness. It’s a record that finds beauty in indulgence, before you realize that indulging in something means unwittingly peeling back the layers to a reveal a deeper meaning. Or maybe it’s just a deeper pain. Does it result from run-of-the-mill totalitarianism? Or the end of a romantic partnership?

Picking apart the lyrics like this may be a fool’s errand when so many of the album’s songs were written at different periods in the band’s career. But just because the words are disparate doesn’t mean there’s not a unified statement at play. It’s less about what the musicians are saying and more about how they’re saying it. It’s about switching out the lungs of each song with new organs that allow every track to breathe the same air. It’s about theme through delivery, theme through nuance, theme through arrangement. It’s about Radiohead’s version of classical music.

— D.C.

04. The Bends (1995)

Runtime: 48:37, 12 tracks

“There are many things to talk about”: Like its predecessor, The Bends is still preoccupied with angst and disorientation, but on a larger scale that turns the spotlight away from Yorke’s personal troubles towards something more global and cryptic: poverty, white-collar discontent, and alienation all get their due. The amped up complexity doesn’t just come from a more experienced worldview either, but an expanded musical palette. The sonic heaviness feels sincere, which means the emotional heaviness does, too, giving the album more stakes, more weight, more oomph.

“Siren singing you to shipwreck”: You don’t have to squint to see why most of The Bends’ songs could be pop if they wanted to — even its most abrasive moments are bound together by digestible chord progressions — but the catchiest tune, “Bones,” didn’t receive any radio airplay, despite five of the 12 tracks being issued as singles. And yet it forever remained a deep cut, keeping the older Greenwood’s Cure-like bass line a secret known to only hardcore Radiohead fans.

“It wears her out, it wears her out”: “Fake Plastic Trees” is a slow dance for sure, but it’s still a dance. We doubt it’s been played at a lot of proms, though, despite its appearance in Clueless.

“Anyone can play guitar”: As if to distinguish itself from Pablo Honey, “Planet Telex” opens the album with the faint howl of wind, probably canned from some barren moon. It also heralds the arrival of the song’s woozy synthesizers, an instrument not used once on the band’s debut.

“For a minute there, I lost myself”: “Black Star” immediately grabs the listener since it begins in the middle of the bridge rather than the first verse. Then, the tempo snaps from 6/4 to 4/4 to start things off proper. It’s subtle, but effective enough to make it stand out from the typical grunge fare of the time.

“Living on Animal Farm“: “Street Spirit (Fade Out)” explores the coexistence of the spirit world and the material world found in Nigerian author Ben Okri’s The Famished Road, and “Planet Telex” was originally titled “Planet Xerox,” until the band realized it was a trademarked term. That’s fine. “Telex” sounds cooler anyway, much more in line with space travel and futurism.

“Out of control on videotape”: Directed by Jamie Thraves, the music video for “Just” feels like an absurdist short play in the vein of Ionesco. In it, a man in a business suit miserably lies down on the pavement, prompting anger and confusion from several passersby on why he would do such a thing, even though he’s not hurting anyone. The ending is too good to spoil here, so if you’re the rare Radiohead fan who hasn’t seen it (or even if you have), give the video a watch and let us know what you think the man’s final statement is in the comments section.

“Get judged”: Radiohead is still just as sulky on The Bends as they are on Pablo Honey, but after two years of touring, they figured out how to channel that sulkiness into something more powerful in its diversity. All three guitarists (Greenwood, Yorke, and Ed O’Brien) learned that there are other ways to convey anger that doesn’t just involve turning up the volume; Yorke learned that as a lyricist, mystery can still have bite and be a lot more interesting to sift through than just plain whininess; and Radiohead’s fans learned that the band could still make good on alt-rock promises while making the listener think just a liiiittle bit more about the words.

— D.C.

03. Kid A (2000)

Runtime: 49:56, 10 tracks

“There are many things to talk about”: On Kid A, Radiohead explored the medium of collage. Scraps of instrumentation and snatches of melody were assembled, cut, and reassembled; lyrics were written in clumps of one or two lines and paired with other clumps for color or contrast. This might make the album seem nonsensical, the central theme impenetrable, but the fragments are the whole point. It’s a perfect wedding of form and content; the album takes place in a confusing world where a bump on the head and “Where’d you park the car?” and nightmares about the kids being cut in half all get rolled into a single ball of anxiety; it’s about the struggle to make sense of all these individual moments, these fragments you don’t understand, all while somehow keeping your sanity.

“Siren singing you to shipwreck”: There’s another version of “Motion Picture Soundtrack” — less singular, more by-the-numbers, with the refrain “I think you’re crazy, maybe” stretched out into a conventional hook, and the backing of strings and a grand piano — that could do quite nicely for whichever brooding songstress finds herself the flavor du jour. “White wine and sleeping pills/ Help me get back to your arms.” And all the sad schoolgirls nod their heads. With a melody simple enough that anyone could hum it and catchy enough that anyone could find it stuck in their heads, “Motion Picture Soundtrack” is like a truffle mushroom: a delicacy that only seems inedible at first.

“It wears her out, it wears her out”: “Idioteque” has a case for being the best dance song on this or any other album, but the title of Kid A’s sneakiest ass-shaker belongs to “The National Anthem.” Consider the individual elements. Item: one bass, muscular and funky. Item No. 2: drums, heavy on the hi-hats, which wouldn’t be out of place on a track by Miles Davis. Item No. 3: Horns, ecstatic, wild, with a hat-tip to bebop and Charlie Parker. Item No. 4: Lyrics as epic and vague as anything heard on a house mix (“Everyone around here/ Everyone is so near/ It’s holding on”). There’s anxiety and discord flitting about the edges, in keeping with the albums overall themes, but the core is imminently danceable.

“Anyone can play guitar”: The modular synth on“Idioteque” is the best example of one of the great accomplishments of Kid A, which was to make machines as emotionally expressive as any traditional instrument. The chord progression is a sample of four bars from an 11-minute computer symphony called “Mild und Leise” by Paul Lansky, itself a riff on an aria of the same name from Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde. With apologies to other influences like Brian Eno, Aphex Twin, and even Paul Lanksy, the tremulous tone of these modular synths — somewhere between an organ and a cello — owes more to Wagner’s romantic operas.

Part of this is a matter of timing; Radiohead was able to take advantage of technologies unavailable to Lansky in the ’70s. Part of the credit belongs to producer Nigel Godrich. But mostly, it’s a testament to the artistic vision of Radiohead, to listen to dozens of different synthetic sounds and say, “Not this… not this… almost but not quite…” until finally arriving at the perfect sound and never saying, “Close enough.”

“For a minute there, I lost myself”: Near the end of “Optimistic,” the rhythm section fades out, only to return several beats per minute slower. Radiohead seems to be putting the brakes on their optimism; it’s almost a bridge between “Optimistic” and “In Limbo,” the former featuring the chorus, “Try the best you can/ The best you can is good enough,” and the latter “You’re living in a fantasy world.” It’s like coming down from a high, a return to cold reality.

“Living on Animal Farm“: “The rats and children follow me out of town,” from the title track. Out of all of history’s great songwriters, I’m not sure any have taken less care than Yorke that their much-labored over lyrics were actually intelligible. That’s especially true on “Kid A,” where his voice sounds like it’s being transmitted through an underwater telephone, and only loud speakers and careful focus will help you distinguish one word from another.

Once understood, the sentences are plain enough, although I’d hesitate to ascribe to them a fixed meaning. The reference to the Pied Piper of Hamelin could be a metaphor for life as a rock star, followed everywhere by vermin and kids. But then, what to make of other lyrics from the same song, like “We’ve got heads on sticks / You’ve got ventriloquists?” It’s probably best to interpret these lyric collages like you would an abstract painting — everything’s meant to evoke a specific mood, not to tell a literal story.

“Out of control on videotape”: For Kid A, Radiohead eschewed conventional music videos and instead released a series of 15-to-60-second promotional “blips.” Designed by Stanley Donwood, the artist who also helped create every Radiohead album cover except Pablo Honey, they run the gamut from “trippy screensaver” to the stuff of nightmares. The thing is the abrupt audio editing and surreal imagery suggest something much stranger than Kid A actually delivers. Perhaps this was intentional; when fans exposed to the jarring blips finally heard the album, they might have been relieved to find fairly conventional song structures and, hiding behind the new instrumentation, Radiohead’s same old gift for melody.

“Get judged”: Kid A has been called “frustrating,” “dull,” and “incomprehensible,” all by smart people, all of whom love music. Even fans who enjoy it could make a case for several other Radiohead albums in higher positions, and they wouldn’t be wrong. Music isn’t sports; there’s no such thing as a clear winner, and our purpose in ranking the albums isn’t to settle debates, but to provoke them. With OK Computer, where the brilliance of the songwriting is only matched by the accessibility of the songs, you can pick any track and play it for nearly anyone who enjoys rock music, and they will likely find something to appreciate. The same cannot be said for Kid A, and so it’ll have to settle for the bronze.

Still, there’s the simple fact that Kid A sounds like nothing else, a marriage of rock ’n’ roll and abstract expressionism. With this album, Radiohead did to music what Pollock and Rothko did to paints, stripping away everything extraneous — all the context and characters and places and stories that had always seemed necessary for popular music and gave us something no less compelling for being abstract and all the more powerful for being pure.

— W.G.

02. In Rainbows (2007)

Runtime: 42:39, 10 tracks

“There are many things to talk about”: Rainbows are faint despite their opacity, warm despite their consistency, and fleeting despite their illusion of permanence. For many, they symbolize the beauty of a world that escapes you as quickly as it welcomed you into it. That’s In Rainbows. Radiohead finally did away with the anger, the politics, and the dystopian worry in favor of crafting something intimate. There’s darkness in several songs, of course, but what In Rainbows chooses to focus on at the end of the day is the transience of life and how our mind walks on a separate path than our bodies.

“Siren singing you to shipwreck”: “15 Step” begins with isolated drums, a good portion of which is fed through Kid A-like electronics. Before Jonny Greenwood’s blissful guitar line slides into the picture as the melody, Radiohead has already created a clean pop song. That skittering drum intro follows in the footsteps of pop songstresses before it, from Amerie’s “1 Thing” all the way to Beyoncé’s “Run the World (Girls)”. There’s no better call to pop than an unstoppable drumbeat, and “15 Step” is Radiohead’s contribution to that pile.

“It wears her out, wears her out”: In Rainbows has its fair share of songs that make you get up and dance, but does it count if it’s buried underneath deep humming and tail-chasing guitars? “Jigsaw Falling into Place” would explode on traditional dance floors if it were composed solely for synths and laptops. Instead, it’s a jittery club hit by way of rock instrumentation. As Yorke begins yelling the lyrics, things melt into a gooey pool of warmth, forming the colorful world of a dance song that makes you lose track of time.

“Anyone can play guitar”: The essential sound of In Rainbows is actually a lack thereof. There’s space in these tracks that doubles their lung capacity, filling the room with more breath than heard on Radiohead’s last three albums. This new depth comes courtesy of Selway and Colin Greenwood, who call and respond to each other with equal parts understanding and playfulness. If not for the interlocked minds of the rhythm section, how else could the spaciousness of “All I Need” or “Nude” sound so haunting?

“For a minute there, I lost myself”: Technically, “Faust Arp” is the only song on the album that changes (god bless that hopscotch-tempo jumping), so the most striking time-signature shift here isn’t actually a time-signature shift at all. “Weird Fishes/Arpeggi” introduces a break from the guitar treading for a couple dozen seconds of muted playback. “I get eaten by the worms,” Yorke sings about three minutes in, flushing everything out while he sing-talks in a daze. The reason “Weird Fishes/Arpeggi” is so comforting is because of its repetition. To suddenly rip that away elevates its original importance. On every listen, that change-up still hits like the shock of ice water in a heat wave: painfully calming, unknowingly necessary, and overwhelming in the best way possible.

“Living on Animal Farm“: “Bodysnatchers” is more than meets the eye. While the title originally brings to mind sci-fi film Invasion of the Body Snatchers, the lyrics’ real origin comes from the 1972 novel The Stepford Wives and Yorke’s fixation with Victorian ghost stories at the time. Thank goodness. It prompted one extra cheeky line, “Your mouth moves only with someone’s hand up your ass,” which sure doesn’t get said enough in songs.

“Out of control on videotape”: Thanks to a storyboard contest with animation website Aniboom, In Rainbows has a wealth of fan-made videos, each worth delving into. Radiohead couldn’t choose a single winner from the bunch, so four different title holders went home with 10 grand each. Most fans will tell you the clear champ is Stefan Hanni and Jan Zaumseil’s video for “Reckoner.” A red creature sits at his kitchen table, despondent, while reflecting on a separation from a loved one. As memories consume him, so does their visual representation — a swirling white cloud — leaving him detached from reality and mirroring the song’s impossible qualities in the way that only animation can.

“Get judged”: Whether they like it or not, Radiohead changed the game with In Rainbows in more ways than one. The album’s pay-what-you-want method gave birth to Bandcamp and dozens of other platforms, lighting a far bigger fire beneath the belly that was illegal downloading at the time. Distribution aside, In Rainbows is a physical album that goes from 0 to 100. Radiohead sweat out a rambunctious fever on only a few songs like “Bodysnatchers” (many more, like “Bangers & Mash,” were dumped on the bonus disc) in favor of slowing things down for the rest of the record without falling prey to the tropes usually associated with balladry.

The airiness of the album is what gives the minute changes such empathetic motion. “Videotape,” one of its more subtle successes, drives this point home as the closer. In Rainbows sees Radiohead open themselves up emotionally without pushing themselves to redefine sound. Instead, they changed the economic side of the industry, creating a spacious album to soundtrack the highs and lows of that revolution as it unfolded — and continues to unfold to this day.

Ed. note: Read more about In Rainbows on our 100 Greatest Albums of All Time list here.

— N.C.

01. OK Computer (1997)

Runtime: 53:21, 12 tracks

“There are many things to talk about”: At its best, science fiction functions as a funhouse mirror, taking real questions about ethics and existence and exaggerating them into aliens, monsters, and problems of time and space. For OK Computer, Radiohead’s third studio album, the band mostly abandoned the moody introspection of The Bends and Pablo Honey in favor of a detached, third-person perspective. It’s a satire of modern life, and in magnifying modern problems, the band tackles extra-terrestrials, androids, and other science-fiction staples. Of course, there’s more: politics as conspiracy, consumerism as religion, love as violence, and personal slights as capital crime. It’s dripping in irony, and like all the best of satire and science fiction, the ironies are covering up a deep well of disappointment.

“Siren singing you to shipwreck”: Bob Dylan’s “Subterranean Homesick Blues” is almost a litany of disaffection — a parade of different characters struggling to fit in and get by. In contrast, Radiohead’s “Subterranean Homesick Alien” is a study of a single lost soul so desperate to feel special that he fantasizes about being abducted by aliens. It has Dylan’s humor, his critical eye, turned on Radiohead’s longstanding preoccupation with loneliness. It’s a nice twist on the tale of an outsider — like a remix of “Creep” done by someone a few years older who wears a smirk instead of their heart on their sleeve.

“It wears her out, wears her out”: Has there ever been a more fun song written about pandering for votes than “Electioneering?” The lyrics, “When I go forwards you go backwards/ And somewhere we will meet,” aren’t just a cynical take on the relationship between elected officials and the public; it could also double as instructions for a line-dancing class. That jaunty guitar riff is one of Radiohead’s great toe-tappers, and there’s even a cowbell to highlight how much fun the politician is having when he says, “I will stop at nothing.”

“Anyone can play guitar”: The talking machine of “Fitter Happier” is one of the more cerebral touches on OK Computer, and the track most likely to be skipped on repeat listens. But that doesn’t make it uninteresting; in fact, it’s proof that Radiohead’s goals had expanded beyond writing great rock songs. On an album full of social commentary, “Fitter Happier” is the track that’s most obviously satirical; in this world, you can do all the things you’re supposed to do, exactly as the experts proscribe, but in the end you’ll wind up a soulless robot.

“For a minute there, I lost myself”: Radiohead like to switch up time signatures the way Shakespeare liked to occasionally veer from iambic pentameter. When a strong rhythm has been established, any deviation will perk up the ear and give a clue to the character’s state of mind. One of the best examples of this is “Paranoid Android.” There are several brief explosions into double-time, and frequent breakdowns from 4/4 into 7/8 — a portrait of a mind that’s racing to conclusions and throwing itself down blind alleys.

“Living on Animal Farm“: The film mentioned in the title of “Exit Music (For a Film)” was Baz Luhrmann’s Romeo + Juliet. Like the movie, the song is a retelling of the Bard’s classic tale of teen suicide, and it has a dramatic, rather than musical, structure. It begins with a slow acoustic guitar and builds in volume instrument by instrument. “Today…” Yorke coos to his Juliet, “We escape.” By the time the violent climax arrives, Yorke is howling in ecstasy that “Now we are one/ In everlasting peace.” His last words are directed at the authority figures whose “rules and wisdom” drove them to their desperate end: “We hope that you choke,” he repeats, fading away to nothing.

“Out of control on videotape”: For “Paranoid Android,” the band engaged Magnus Carlsson, creator of the alt-animation Robin, to draw their music video. The resulting surreal comedy stars the title character of Carlsson’s show, along with his best-friend Benjamin. The band members make a cameo at about 2:34, sitting at a table in a bar, watching a man dancing while a human head projects out of his stomach.

“Paranoid Android” isn’t typical of Radiohead during the period. They tended to favor simple, stark videos: Yorke singing with his head in a bowl that was slowly filling with water (“No Surprises”) or a car chasing down a man in slow motion (“Karma Police.”) Radiohead may come across as self-serious at times, but this shows a lightness in their decision making; sometimes, you just like a cartoon, and so you call the guy who made it.

“Get judged”: OK Computer was Radiohead’s most ambitious project to date, a funhouse mirror large enough to show the whole warped world. Here, Yorke is at his storytelling best, living right at the knuckle of satire and sentiment. The album was universally adored, a global hit, the kind of career-defining moment that would allow any band to tour successfully — and live comfortably — for years. Most of the time that would be a good thing, but for Radiohead, it came with its own set of problems. They had achieved mastery over their instruments and pushed their particular brand of guitar-driven rock as far as it could go.

Later, they would push even further, taking their themes of alienation out into space and, in the process, alienating huge swathes of critics and fans. But for one album they managed to straddle the two worlds: the accessible rock’n’roll of their early years and the later wild experiments. For one glorious moment, they were everybody’s darling.

Ed. note: Read more about OK Computer on our 100 Greatest Albums of All Time list here.

— W.G.

Every Radiohead Album Ranked From Worst to Best

Consequence Staff

Popular Posts