A Definitive Ranking of David Lynch’s Movies

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

The post A Definitive Ranking of David Lynch’s Movies appeared first on Consequence.

Welcome to Dissected, where we disassemble a band’s catalog, a director’s filmography, or some other critical pop-culture collection in the abstract. It’s exact science by way of a few beers. This time, we dive into the wild, weird, beautiful, and terrifying brain of David Lynch. This article originally ran in 2017 and has been updated.

David Lynch is about mood. He’s about feelings. He’s about triggering something deep within all of us. For over four decades, the American filmmaker has twisted the senses of his audiences, blurring whatever lines exist between reality and somewhere else. It’s why he’s often considered an eccentric auteur, an untraditional talent in an industry that capitalizes on the traditional. But for all his quirks and chaos, there’s an assured vision, one that isn’t going for the weird for weird’s sake, and that’s what separates him from anyone who opens a strange door to simply find strange.

“I learned that just beneath the surface there’s another world, and still different worlds as you dig deeper,” Lynch once explained of exploring his grandfather’s apartment building in Brooklyn. “I knew it as a kid, but I couldn’t find the proof. It was just a feeling. There is goodness in blue skies and flowers, but another force — a wild pain and decay — also accompanies everything. Like with scientists: they start on the surface of something, and then they start delving. They get down to the subatomic particles and their world is now very abstract. They’re like abstract painters in a way.”

Whether he’s subverting the soap opera with eerie mountain towns or chewing on voyeurism through ripped ears, Lynch is always digging at and cracking whatever surface we may or may not have known was even there. While we don’t always fully grasp what he’s wrestling with — see: anyone who was involved with or has seen 2006’s Inland Empire — it’s impossible not to at the very least admire what he’s brought to the silver screen. Every go-around, Lynch offers a divine experience, and as such, there are few filmmakers more deserving of a complete dissection.

To paraphrase Frank Booth: “Here’s to David!”

— Michael Roffman

10. Dune (1984)

Runtime: 2 hr. 17 min.

Cast: Kyle MacLachlan, Virginia Madsen, Francesca Annis, Leonardo Cimino, Brad Dourif, José Ferrer, Everett McGill, Jack Nance, Patrick Stewart, Dean Stockwell, Max von Sydow, Alicia Roanne Witt, Sean Young … and Sting

The Long Pitch: In a strange, far-off future, “spice” reigns, a space-travel aiding substance only found on the desert planet of Arrakis. Paul Atreides, son of Duke Leto Atreides, leads his people, the Fremen, in a battle for control of the planet against the Harkonnens and the rulers who sent his father to the desolate Arrakis to be killed in the first place.

The Short Pitch: It’s the adaptation of a Frank Herbert sci-fi epic novel that many still believe to be un-adaptable.

The Elephant Man: Dune flopped, in large part, because it was an adaptation that may be difficult to follow had you not read the source material. There are just so many characters, strangely vowel-ed words, and interweaving relationships to try to wrap your head around. In the midst of that very mire of confusion and conflict, though, stands the mighty Brad Dourif, everything about his actions, speech, and essence vibrantly clear. As Piter De Vries, aide to the villainous, grotesque Baron Vladimir Harkonnen, Dourif gleefully and meticulously carves away at everything around him.

Dourif’s other largest roles were the voice of killer doll Chucky in Child’s Play, the slippery Wormtongue in the Lord of the Rings films, and the mental patient Billy Bibbit in One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest. So, you get the idea of the type of character he’s best suited to. As such, De Vries isn’t your average sycophant assistant; he’s a Mentat, a human trained to essentially become a living computer. He’s twisted and ragged, so fidgety in his mental capacity that he may even be one step ahead of the fact that Harkonnen will wind up killing him — but so well trained and loyal that he follows anyway. And Dourif knows how to handle that kind of twisted subtlety, delivering pathos and massive scenery chewing in equal doses.

Candy-Colored Clowns: As a sci-fi epic, the villains of Dune are appropriately monstrous. It’s hard to imagine considering any one of them all that lovable, per se. But if there’s one with a strange, confusing power — a performance so unexpected and off that it’s hard to look away — it’s Sting as Feyd-Rautha. Yes, that Sting. The Police Sting. With a shock of Heat Miser hair, a blue jumpsuit, and a seriously collared jumpsuit. He’s not the best actor in the film, to say the least, but there’s a real magnetism to his barking and sneering.

The Baron’s nephew, Feyd-Rautha is a wicked, clever, cruel enforcer of the Harkonnen family, long-planned to ascend to the place of Kwisatz Haderach (seriously, read the book first). He is installed as the anti-Paul, the opposite of everything Kyle McLachlan represents. And if you’re going to try to think about the opposite of Kyle McLachlan, Sting isn’t exactly a natural first thought. But he clearly wants to be thought of as that extreme evil, throwing every breath he has into the climactic dagger duel. You can’t help but follow his every move, wondering how exactly this all happened.

In Dreams: Oh boy. Picking out a single most surreal moment from Dune is quite the challenge. This one’s a clusterfuck of dreamscape insanity, a filmic totality of “Wait, what?” experiences. But, well, the giant, floating tumor near the movie’s open might take the cake. The Guild Navigator is a humanoid creature able to travel through interstellar space through intake of mass quantities of spice, leaving them mutated, distorted, and otherwise icky.

Lynch’s version of the Navigator is particularly gross, a peanut/testicle goober floating in a tank, wheeled into frame to meet with José Ferrer’s emperor to discuss their plan to kill Paul. Attended by some creeps in black leather robes into the giant, golden hall, the Navigator is stomach-turning enough to make Baron Harkonnen seem relatively normal. And let’s not even get started on the closeups on its folding, flopping “mouth.” Sure, Herbert described the Navigator as a mutated blob, but this … this is some Lynch shit, right here..

Radiator Songs: In a film full of head-scratchers, the soundtrack is one of the biggest. Though he would go on to develop close working relationships with other, perhaps darker, more emotionally charged musicians, this space epic is scored almost entirely by Toto. Just a couple years after blessing the rains down in “Africa”, David Paich, Steve Lukather, and the gang were headed to space with genuine weirdo David Lynch, the Vienna Symphony Orchestra, and the Vienna Volksoper Choir in tow for good measure. Oh, and Brian Eno contributed a single track.

Tonally, the entire film is a bit messy, so it should come as no surprise that the soundtrack falls prey to that same problem. From grand symphonic explosions to tinny harpsichord suites, there’s a kind of Mannheim Steamroller vibe to the proceedings, nowhere near the high drama that the source material would seem to call for. The music itself isn’t bad; it’s just a mismatch. The soft, chilled strings of “Trip to Arrakis” and Eno’s wandering electronics on “Prophecy Theme” have little to do with each other, though each is affecting in its own right — much like the cobbled-together feel of the film itself.

The Black Lodge: It’s not uncommon for sci-fi to blend the futuristic and the ancient, but the emperor’s grand halls still felt unique and lux. Tons of gold, mechanic symbology, rods sticking out at every odd angle, the thing feels like a blend of Egyptian grandeur, the riches of a wayfaring society, and the shiny metal and leather of an ’80s futurism. It may not be as iconic or timeless as anything from Star Wars, but it’s a sci-fi look all its own.

A Beginning Is a Very Delicate Time: Lynch tends to continue to work with certain people frequently, and Dune acts as an early touchstone for several actors that would go on to become regulars in the director’s oeuvre. The film marks the first appearances of Kyle Maclachlan, Everett McGill, and Alicia Witt, as well as the second appearances of Jack Nance and Freddie Jones. But while he poached some actors from the cast that would become favorites, it’s telling that the composers, designers, editors, and the like that would become his primary posse weren’t taken from the Dune credits.

Lynch on Lynch: “Dune … it wouldn’t be fair to say it was a total nightmare. But maybe 75% nightmare. And the reason is I didn’t have final cut. I had such a great time in Mexico City, the greatest crew, cast, it was beautiful. But when you don’t have final cut, and I knew this already … but why did I do it? I don’t know. But when you don’t have final cut, total creative freedom, you stand to die the death. Die the death. And die I did. When you have a failure and they say there’s nowhere to go but up, it’s so freeing. It’s beautiful, in a way.”

Analysis: This could’ve been just another terrible sci-fi bomb, but there’s just enough weirdness in the mix to make this a train wreck worth watching. It’s become a cult view for a reason: It’s not good enough to be a classic, but there are enough hints of the Lynch persona underneath the mess to want to pick at it like a scab and track down what might have been had he been allowed full creative control. There are many different cuts of the film, all showing various levels of weirdness, of forced studio control, of ambition, of compromise. And yet there’s still something there, something worth searching for. And how can this be? For he is the Kwisatz Haderach!

— Adam Kivel

09. Twin Peaks: Fire Walk with Me (1992)

Runtime: 2 hr. 14 min.

Cast: Sheryl Lee, Ray Wise, Moira Kelly, Chris Isaak, Harry Dean Stanton, Kyle MacLachlan, Kiefer Sutherland, David Bowie, and a handful of favorites from the television series minus Lara Flynn Boyle, Sherilyn Fenn, and a few more notable absentees

The Long Pitch: Two FBI agents are sent to Deer Meadow, Oregon, to investigate the mysterious disappearance of a young teenager named Teresa Banks. A year later, we discover a similar evil has plagued the town of Twin Peaks, Washington, by following the final footsteps of another troubled teenager named Laura Palmer.

The Short Pitch: It’s a prequel to Twin Peaks that you really shouldn’t watch until you’ve seen the entire series.

The Elephant Man: When we first step into Twin Peaks, during the show’s iconic 1990 pilot, we’re quickly introduced to the corpse of Laura Palmer, and it’s through her death that we meet the townspeople, the agents, and the weirdos. So, one of the few joys of Fire Walk with Me is being able to watch Sheryl Lee play a character fans and viewers previously only knew through snippets of journal entries, blurry VHS tapes, or pretzeled depositions offered up to Agent Dale Cooper, Sheriff Harry S. Truman, or one of the many teenagers channeling their inner Nancy Drew.

This idea was also an intriguing proposition to Lee, who saw the film as something of a wish-fulfillment, a way to come full circle with the character by playing her in the flesh rather than in spirit. To her credit, especially given the film’s messy screenplay, she really cuts deep into the role and offers up a sobering performance of a tortured and frightened victim. Sure, she’s a tragic figure, but everyone also talks about her liveliness, and although the film’s story doesn’t exactly warrant the latter, Lee tries her best to toe that line, and the proof is in the pudding creamed corn.

Candy-Colored Clowns: It’s a real Sophie’s Choice to pick any favorite villain out of Twin Peaks, but for Fire Walk with Me, the dark and gloomy throne belongs to the one and only Ray Wise as Leland Palmer. The would-be lovable father turns real ugly in the most jarring way, and while longtime viewers of the series know he will eventually find peace and serenity somewhere in the second season, it’s how he sputters out of control into madness here that’s both thrilling and terrifying. And that’s not an easy task when you’re wrestling with a lewd, incestuous relationship that leads to a rape and a murder.

But Wise, who was then already a veteran television actor, plays it with such pride. Granted, much of that has to do with the preceding 18 episodes he had just wrapped up for ABC, but there’s a certain energy to his performance here that speaks to a larger agenda. Maybe it had to do with the fact that this was a big screen role, an opportunity that hadn’t really come his way, at least not with anything this substantial or nuanced. Or maybe he just really loved the role and knew this was likely his proverbial Swan Song. Either way, he lights up the screen every time he appears, and you can only marvel.

In Dreams: One scene worth revisiting is the maddening traffic jam involving Leland, Laura, and MIKE. Due credit goes to Lynch — and yes, the frenzied performances of Wise, Lee, and Al Strobel — for being able to invoke such palpable chaos under the guise of a sunny day in the Pacific Northwest. The way he pivots between the perspective of each character and slowly orchestrates the bubbling tension, from MIKE’s erratic driving to Leland’s panicked gaze to Laura’s dire confusion, is just brilliant.

To add to the cartoonish surrealism, Lynch pairs this conflict with a geriatric couple that’s struggling to cross the street, almost as if they’re stuck in the type of unseen quicksand that clings to our feet when we dream. How they block all the cars, including the Palmers’ convertible, highlights the film’s underlying theme of child abuse by both subtly framing Leland’s grasp over his daughter and bottling the claustrophobic feelings of Laura’s own inescapable fate. It’s mystifying stuff, but with a purpose.

Radiator Songs: At this point, Lynch and composer Angelo Badalamenti were best buds, having worked together on 1986’s Blue Velvet, 1990’s Wild at Heart, and two seasons of Twin Peaks. So, by the time Fire Walk with Me came along, Badalamenti was pretty comfortable with Lynch’s strange, mountainous world, and that assuredness bubbles through in the film’s score. Rather than lean heavily on past compositions, which he could have easily done without much protest from the fans, Badalamenti offered up a completely new score, one that’s much broader in scope and complete with more risks.

For one, it’s louder. Jazz vocalist Jimmy Scott, longtime collaborator Julee Cruise, and even Badalamenti hit the microphone to sing a little poetry by Lynch, who contributed lyrics to “Sycamore Trees”, “Questions in a World of Blue”, “A Real Indiction”, and “The Black Dog Runs at Night”. The end result is something that sounds stripped right out of a lounge, which makes sense given that so much of the action takes place at the lascivious Bang Bang Bar. Still, fans will no doubt recognize the softer, ambient tones, as evidenced by the film’s title track, which sounds like a reimagined version of “Laura’s Theme”.

The Black Lodge: If fans thought One-Eyed Jacks was sleazy and dangerous, they probably cowered in fear after revisiting the Bang Bang Bar with Laura and Donna (who, by the way, was played by Moira Kelly and not Lara Flynn Boyle). Lynch was still a few years removed from 1997’s Lost Highway, but in hindsight, this whole club set feels like one abrupt prelude. It’s a stylish hell, where the danger is embellished by needling strobe light, ruby filters, filthy men like Walter Olkewicz’s unbearable Jacques Renault, and the repetitive shuffle of Badalamenti’s scintillating track “The Pink Room”. But you totally get why this dive would be appealing to two small-town teenagers hungry for rebellion and yet why it would lead to nothing but pure evil.

The (Disappearing) Thin White Duke: Early in the film, David Bowie makes an all-too-short cameo as Agent Phillip Jeffries, who warns his colleagues — ahem, FBI Regional Bureau Chief Gordon Cole (Lynch) and Special Agent Dale Cooper (MacLachlan) — about seeing the Man from Another Place, Killer Bob, Mrs. Chalfont, and her grandson before vanishing into oblivion. It’s a blink-and-you’ll-miss-it cameo that would have been a little more important had they not cut out some of the footage.

Originally, Bowie was to appear in a larger scene where he would have been transported from a hotel in Buenos Aires, Argentina, and into the FBI offices, confused by a calendar that reads 1989. As Bowie told The Seattle Times in 1991, “They crammed me. I did all my scenes in four or five days, because I was in rehearsals for the 1991 Tin Machine tour. I was there for only a few days.” Reportedly, producers tried to get him for the forthcoming revival, but they were sadly too late.

Fire Walk with Production: If you couldn’t tell from the Bowie anecdote, or the subtle hints peppered throughout this entry, Fire Walk with Me was something of a clusterfuck. Running off the coattails of the then-just-canceled show, which some of the cast felt was a result of Lynch and co-creator Mark Frost jumping ship mid-second season, production on the film was a little topsy-turvy, made all the more problematic when MacLachlan opted to return only for a minor role, forcing Lynch and co-writer Robert Engels to rework the screenplay, which really only complicated matters further.

But wait, Robert Engels? Why wasn’t Frost involved? You’re starting to get the picture. Without his original co-conspirator, who waved bye bye to direct his own movie (see: 1992’s Storyville), Lynch instead worked with Engels, who had previously written nearly a dozen episodes for the series (including what would be the series finale). It also doesn’t help that five hours of footage was condensed to two hours, resulting in the dismissal of characters like Sheriff Truman, Dr. Jacoby, Deputy Brennan, and Lucy Moran. Then again, one might argue (including Lynch), that those characters were superfluous to Laura’s core story.

Lynch on Lynch: “At the end of the series, I felt sad. I couldn’t get myself to leave the world of Twin peaks. I was in love with the character of Laura Palmer and her contradictions: radiant on the surface but dying inside. I wanted to see her live, move, and talk. I was in love with that world, and I hadn’t finished with it. But making the movie wasn’t just to hold on to it: it seemed that there was more stuff that could be done. But the parade had gone by. It was over. During the year that it took to make the film, everything changed. That’s the way it happens, sometimes. And then there’s this thing about turning on people. It’s so natural, in a way. It happens to so many people.”

Analysis: To put it bluntly, Fire Walk with Me is a mess, a feature film that was both fumbled in the editing room and lost when Lynch and Frost refused to reunite. Having said that, it’s a revelatory experience for die-hard fans of the series who not only wanted closure but a better sense of understanding, which goes along with Lee’s thoughts on why she wanted to revisit the role of Laura Palmer. Watching this film adds a depth to the series that goes way beyond Damn Good Coffee or little soliloquies about Douglas firs. When you look past the Red Room, you’re left with a tragic story of incest, and there’s a certain darkness to that realization that makes Fire Walk with Me hard to dismiss. It’s just a shame the film missed the mark.

— M.R.

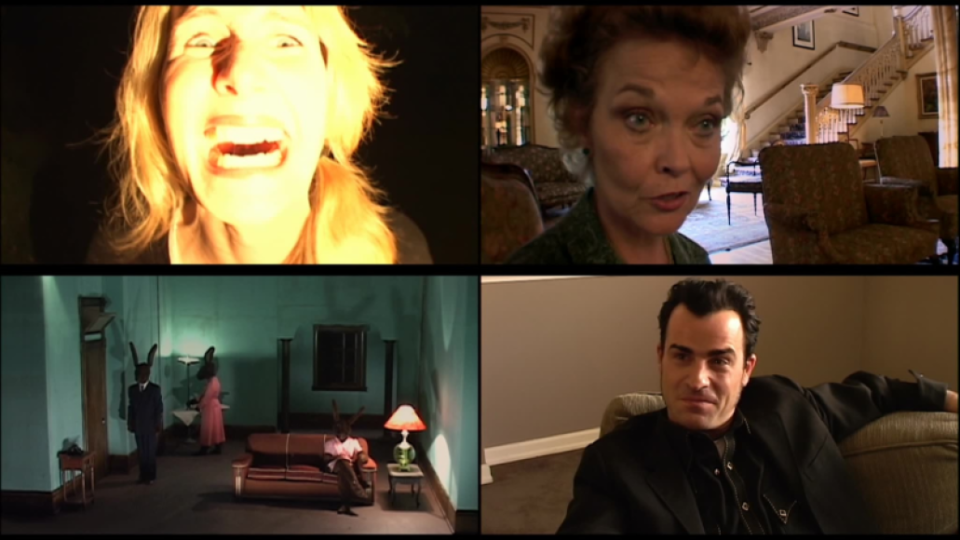

08. Inland Empire (2006)

Runtime: 3 hrs.

Cast: Laura Dern, Jeremy Irons, Justin Theroux, Karolina Gruszka, Peter J. Lucas, Harry Dean Stanton

The Long Pitch: Nikki (Dern), an actress looking for her comeback, finds her way into a film where she’s set to costar with Devon (Theroux), a known skirt-chaser. They’re told that the film was previously attempted, but never completed due to the deaths of its leads. As the film’s production goes on, and Nikki finds herself falling deeper and deeper into the role of Sue, an abused woman with a collapsing marriage, Nikki/Sue’s reality is torn away from all chronology, intersecting with disparate stories of a prostitution ring, human trafficking, hypnotism, humanoid rabbits, and the encroaching menace of a red-lipped man.

The Short Pitch: David Lynch wanders through the subconscious of his filmography, which itself is largely concerned with the subconscious, sending the viewer down a rabbit hole for three memorably frustrating hours.

The Elephant Man: Lynch has never had a problem recruiting name actors to appear in strange, sometimes meager roles in his films, and so William H. Macy appears just to make announcements on a show within the movie, and Terry Crews briefly appears as a man on the streets. That’s to say nothing of the film’s bizarre finale, in which Ben Harper, Natasha Kinski, and others appear at a joyous party in Nikki’s home. Also, listen hard to the rabbit portions of the film, and you may hear Naomi Watts’ voice, a carryover from a previous Lynch project.

Candy-Colored Clowns: Even more so than in Mulholland Drive, Inland Empire takes a particularly bleak view of Hollywood as a carnival of fear and inhumanity. The villains, such as they are, exist in the periphery for the most part. There’s the aforementioned red-lipped man (who’s eventually shot and turned into a series of increasingly disturbing hallucinations) and a hypnotist known as the Phantom whose sinister presence hovers over the whole of the film. If anything, it’s the film’s dystopian Hollywood that serves as its most menacing presence, a place in which the constant threat of “consequences” hangs over every personal interaction.

In Dreams: Much of Inland Empire assumes the cadence of a waking nightmare, in which there are few tethers to any kind of familiar reality, and when the “film” within the film ends, it’s merely preamble to the film’s truly unnerving final half hour, an accumulation of terrifying imagery trading on the simple, universal phobia of things not being as they should be that Lynch has used to such stellar effect throughout his career. It’s a wildly disorienting film, and it’s unclear how much of the film occurs outside of the realm of the unconscious after the first few minutes.

Radiator Songs: A substantial amount of the film was shot in Poland, and so Lynch collaborated on the score with Marek Zubrowski, in addition to contributing several other pieces to the film. Krzysztof Penderecki and the National Polish Radio Symphony Orchestra also account for much of the film’s ambient, unnerving sounds. A couple of additions go outside of Lynch’s realm, specifically Beck’s “Black Tambourine” (Guero was released during the film’s production) and Nina Simone’s “Sinnerman” (which plays over the end credits). It’s a fascinating hybrid of pop sounds and otherworldly ambience — in other words, a Lynch soundtrack.

The Black Lodge: Rarely have Los Angeles and Hollywood looked seedier, and it’s not just because of the film’s generally dark visuals. By using the Tower Theater (see: the late-film screening of On High in Blue Tomorrows), Hollywood Boulevard, and a selection of other normally glossy locations, Lynch manages to envision a version of Tinseltown that almost appears to be melting, warped into something grotesque even as life goes on otherwise. The settings sometimes feel more like dressing than Lynch’s locales normally do, but they effectively invert the money and privilege of their surrounding world.

Gone Digital: Like so many filmmakers in the mid-2000s, Lynch transitioned to digital photography for the first time at feature length with Inland Empire. Like many of those films, it’s not the most aesthetically pleasing movie in the world. It’s less distracting here, however, in that Lynch’s aim is for an unpleasant piece. There are points, particularly in scenes featuring a high amount of light, at which Inland Empire looks more like a student film than it should, but it also lends the film a kind of fly-on-the-wall naturalism that makes its complete decline into mania all the more haunting. It’s a bold choice and one that’s less garish now than it was at the time. (Seriously, go back and watch it. It’s just as challenging as you recall, but probably not as bad.)

Dern on Lynch: Lynch’s frequent lead, on her experience with the film: “The truth is I didn’t know who I was playing — and I still don’t know. I’m looking forward to seeing the film … to learn more.”

Analysis: Inland Empire is one of those films that’s almost more interesting as a form experiment. Even by Lynch’s loosely narrative standards, his most recent film is a drift through a series of the director’s pet concepts: sexual indiscretion, shadow conspiracies, the alternate glitz and horror of the film industry, the unconscious mind, the alternate reality of dreams. It’s a demanding piece of work and one that continues to polarize even Lynch’s most ardent appreciators. But Dern’s exceptional, complicated performance accounts for quite a bit; she manages to externalize dense material in a way that gives the film a resonance that its scattershot approach doesn’t necessarily warrant. Inland Empire is among the closest Lynch has come to transposing the disquieting horror of so much of his experimental short-form work to a feature-length project. Whether that’s a positive or not is really up to the viewer.

— Dominick Suzanne-Mayer

07. Lost Highway (1997)

Runtime: 2 hr. 14 min.

Cast: Bill Pullman, Patricia Arquette, Robert Blake, Balthazar Getty, Robert Loggia, Gary Busey, Michael Massee, Richard Pryor, Marilyn Manson, Henry Rollins

The Long Pitch: Los Angeles saxophonist Fred Madison (Bill Pullman) and his wife (Patricia Arquette) start receiving mysterious phone calls and VHS tapes of the interior of their house and the two of them asleep in bed. After Fred has a mysterious encounter with a kabuki-makeupped stranger, he returns home to find another tape, this time depicting his dead wife. He’s convicted of murdering her, at which point he inexplicably morphs into a young mechanic and begins leading a new life with its own ties to the strange man in the makeup and the dead woman.

The Short Pitch: David Lynch does late-’90s noir with the help of some fellow grade-A nutcases and oddballs and music from Nine Inch Nails and Rammstein.

The Elephant Man: In the ’40s, he was a child actor. In the ’60s, he starred in In Cold Blood. In the ’70s, he was disguise-friendly eccentric undercover cop Baretta. In the ’00s, he was a C-list celebrity in a high-profile murder case. Lost Highway lands somewhere in the gray area in between. To put it kindly, he wasn’t exactly on a hot streak, this was his last acting role, and he certainly wasn’t known for turning in daring performances in surrealist films. And yet there’s an undeniable power to Robert Blake’s role as the strange, pale, unblinking man in the black robe.

Blake’s anger is palpable, a violence seething at his core that seems about to break despite the fact that he basically doesn’t move. As he first enters the scene, a swank L.A. party goes silent, his presence a vacuum. He can be two places at once, speak without moving his mouth. He’s a surreal, evil presence in the truest sense, encroaching from the edges and tearing reality apart. It’s difficult to say whether Blake would’ve had stranger choices to make after this one had he not wound up liable for his wife’s wrongful death a few years later. But for one movie, Robert Blake showed signs of a potential comeback, perhaps tied to a real anger inside.

Candy-Colored Clowns: Robert Loggia is the kind of guy that you buy as getting so mad about the specifics of the driver’s manual that he’d chase you down to lecture you about it. But if you only know him from jumping up and down on a piano in Big, you’d expect that lecture to come with a stern, dad-like warning, not a sharp kick to the ribs.

But as Mr. Eddy, gangster boss, Loggia’s warnings against tailgating and statistics about how many people are killed in car wrecks come with as much pain as they do nervous laughter. The dude’s an amateur porn producer with a violent streak and a couple of trained thugs. Loggia isn’t onscreen a whole lot, but for the driver’s manual scene alone, he makes quite the impression. If you’ve seen this one, I’d wager you’re not spending much time tailgating on the highway.

In Dreams: Lost Highway is certainly a surreal film, but it’s more surreal situationally than it is in its imagery. Sure, Bill Pullman transforms into Balthazar Getty and all that, but on the Lynch surreality scale, that one’s not all that strange (doppelgängers have long been a favorite trope of the director).

So, to pick out a most surreal moment, it seems fitting to loop back to the presence of the Mystery Man, Robert Blake. His arrival at the L.A. party is the match on the powder keg established by the grainy, slow-panning surveillance footage of the video tapes. Somehow, the giant, outdated cellphone makes him even more outlandish, floating in, handing Fred the phone, and then speaking to him from the other end. “As a matter of fact, I’m there right now.” Seeing the Mystery Man laugh and hearing it doubled on the phone is a real nightmare moment.

Radiator Songs: While Lynch has masterfully played with time, this one perfectly plays on the shadowy corners of industrial modernity. It also captures a specific place, the old hollywood of noir chased away by the encroaching darkness. Set in L.A., ostensibly around the time it was produced, the mid-to-late ’90s, the soundtrack bumps back and forth between Fred’s extreme jazz, Angelo Badalamenti’s classic cinema score, and contemporary rock grind. Contributions from Marilyn Manson and Rammstein amp up the seaminess, and Trent Reznor’s chugging “Driver Down” fits the manic racing feeling of hurtling down a dark highway at night.

But the cherry on top is David Bowie’s “I’m Deranged”. The song plays in the opening and closing credits of the film, the insistent electronics draining and drilling when married to the frantic footage of the unending center line of a highway lit only by headlights. “I’m deranged/ Down, down, down,” Bowie sings, further leading down the surreal, grimy rabbit hole. The jazz sax and German industrial may tip the scales into cartoony from time to time, but that’s a key to Lynch’s aesthetic too. You won’t likely be playing this soundtrack on an afternoon at home, but it sure gets the heart pumping and fits the film to a T.

The Black Lodge: The Madison household transforms much the same way as the film’s main characters — and, really, the film itself. In a certain light, it seems pretty nice: a recognizably Los Angeles exterior with flowering trees, open space inside, minimal, clean decor. But seen through the grainy VHS camera, suddenly all that space feels claustrophobic, the exterior like a castle tower, the minimalist interior full of looming corners and sharp edges. It’s fitting that Lynch himself actually owns the property and designed much of it himself, inside and out. That shifting attribute is essential to his entire body of work, and this changing structure becomes the rotten core of this film, the scene of the crime.

I Want You To Obey the Rules of the Goddamn Road: There were some serious detractors to the surreal, cyclical Lost Highway. On their review show, Siskel and Ebert gave the film two thumbs down. Ebert’s review opens on a pretty killer critique: “David Lynch’s Lost Highway is like kissing a mirror: You like what you see, but it’s not much fun, and kind of cold.” But that kind of review couldn’t keep Lynch down. In fact, he apparently called their verdict “two more great reasons to see Lost Highway” and would put the words “TWO THUMBS DOWN!” in bold across the top of newspaper advertising.

Lynch on Lynch: “You can say that a lot of Lost Highway is internal. It’s Fred’s story. It’s not a dream: It’s realistic, though, according to Fred’s logic. But I don’t want to say too much. The reason is: I love mysteries. To fall into a mystery and its danger … everything becomes so intense in those moments. When most mysteries are solved, I feel tremendously let down. So I want things to feel solved up to a point, but there’s got to be a certain percentage left over to keep the dream going.”

Analysis: Lost Highway presents Lynch at a key moment in his career, a transition into the fractured identities of Mulholland Drive and Inland Empire. The film loops into itself, characters speaking with each other and even transforming into each other across time, doppelgängers and rejections of reality lurking around every corner. Lines are repeated, voices are doubled, specific answers are questioned and denied. With the O.J. Simpson case fresh on people’s minds, the story of a deluded killer/case of mistaken identity/wrongfully accused man on the run in Los Angeles felt so present, Lynch exploring the inner creases of the modern mind.

— A.K.

06. The Straight Story (1999)

Runtime: 1 hr. 52 min.

Cast: Richard Farnsworth, Sissy Spacek, Everett McGill, Harry Dean Stanton, Kevin & John Farley, John Lordan, a John Deere tractor.

The Long Pitch: Based on a true story, the film follows Alvin Straight, a taciturn veteran who discovers that his estranged brother has recently suffered a stroke. Determined to see him despite his fledgling physical health and his inability to drive a car, Straight sets out with a tractor and an attached trailer to drive from Iowa to Wisconsin. Along the way, he crosses paths with a host of wayward souls in the middle of America, just trying to get to wherever they need to be.

The Short Pitch: Honestly, that’s it for this one. The Straight Story is a simple, forthcoming film by design and really the most straightforward film of Lynch’s entire career.

The Elephant Man: It’s not that Richard Farnsworth was an unrecognizable face by the time he took the role of Alvin Straight, but the circumstances under which he delivers his Oscar-nominated turn were remarkable. Farnsworth was 79 years old and terminally ill with bone cancer when Lynch cast him in the film, and the general paralysis of his legs was unsimulated. Farnsworth pushed through the production despite this, and though he passed away the year after the film’s release, his final performance stands as one of the more resonant turns in the director’s filmography.

Candy-Colored Clowns: The villain in The Straight Story is intangible, because in this case it’s the immovable concept of aging. Sure, there are various instances of panic involving a runaway tractor or some inclement weather, but it’s a film full of generally kind people, and so the real terror exists at the margins, popping up when Alvin collapses in his kitchen and can’t get himself up, or when he laments that the worst part of getting older is “remembering when you were young.” It’s not a subject Lynch treats as fearful, necessarily, but the pragmatic reality of death as an eventual companion hangs over the proceedings.

In Dreams: The Straight Story, as suggested by its title, isn’t really interested in the hard surrealism of so much of Lynch’s work, but he manages to transpose that approach to the simple oddities of everyday people to uncommonly profound effect. It’s a deadpan film, and probably one of Lynch’s funnier movies (at least, by his standards), and the flat, distinctly Midwestern cadence of so many of Alvin’s interactions with strangers dip a toe or two into Twin Peaks territory without making too much of a show of it.

One encounter with a pair of bickering twin salesmen sticks out in this regard, as does a fitful encounter with a harried woman who can’t seem to stop hitting deer and destroying cars on her daily commute. It’s a film more interested in jovial peculiarities, but the touches are there.

Radiator Songs: Once again, Angelo Badalamenti handles the score, but The Straight Story takes a light touch. Much of Badalamenti’s work focuses on the sort of gentle, acoustic sound that Alvin might favor, and it’s one that absolutely suits both the character and the film. The score’s country sensibilities are occasionally subverted, particularly in the more haunting opening and closing pieces, but it’s a gentle, more tonally understated arrangement here.

The Black Lodge: One of the great accomplishments of the film is its use of real locations as set dressing for a version of America that’s at once bygone and completely modern. Lynch has such a firm handle on the modest bars and farmyard houses that form the film’s universe that it almost feels interruptive when a legion of cyclists on modern machines cut through the road Alvin’s on or when he’s offered a brief ride in a car.

There’s an overall emptiness to The Straight Story that Lynch emphasizes in nearly all of Alvin’s chance meetings, the endless rows of corn and expanses of road forming a sort of closed ecosystem in which human kindness is unquestionable and danger only exists by one man’s own actions. So it’s really the human element that offers the film’s most unusual setpieces, rather than any of their surroundings.

That said, the juxtaposition of Alvin’s fevered terror when he loses control of his vehicle on a hill is cut rapidly with a burning house being used for a firefighter exercise, and it’s the most Lynchian piece of imagery in the film in a walk.

When You Wish Upon the Stars: Perhaps the most unconventional thing about The Straight Story is that it was released by Disney, of all studios. After its well-regarded premiere at Cannes the same year, ol’ Uncle Walt’s namesake released a David Lynch film, which just feels strange to say out loud. That said, it’s perfectly in keeping with Disney’s long-running side industry of feel-good true story adaptations, though it’s a more substantial piece of filmmaking than the majority of those.

Lynch on Lynch: Asked about his fidelity to Alvin Straight’s actual story and the minor liberties taken, Lynch once remarked that “the essence is the stuff, and the essence holds the little micro-particles that dictate the action and the thing that drives it. You`ve got to be true to the essence of it.”

Analysis: The Straight Story is based on the kind of event that could have easily been turned into a comforting piece of hokum in a less ambitious filmmaker’s hands. But Lynch, who shot the film chronologically in order to maintain a sense of Straight’s slow-but-unyielding momentum, manages to turn an old man’s tractor ride across multiple states into a nuanced tale of salvation. It’s largely just a collection of odd chance encounters, some poignant and others bizarre, but Lynch finds the soul in Alvin’s journey. It’s an unseemly film for the director until it reaches its touching, barely spoken end, at which point Lynch’s play comes into focus: Other people, even the weird or hurting ones, are all we really have in this life. They make the world worth existing in. And for the cruelty of so much of the director’s work, The Straight Story is a celebration of a kind hand and the determination of the human spirit.

— D.S.M.

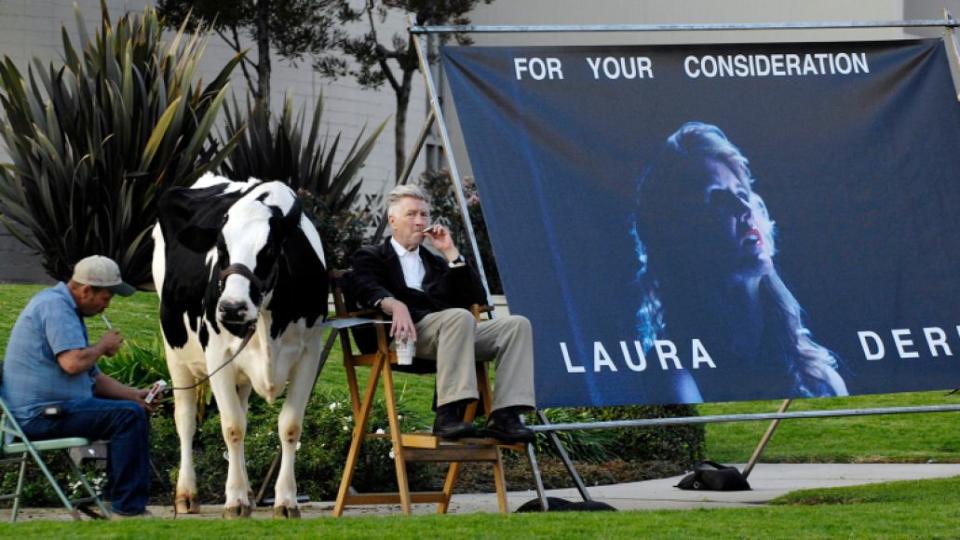

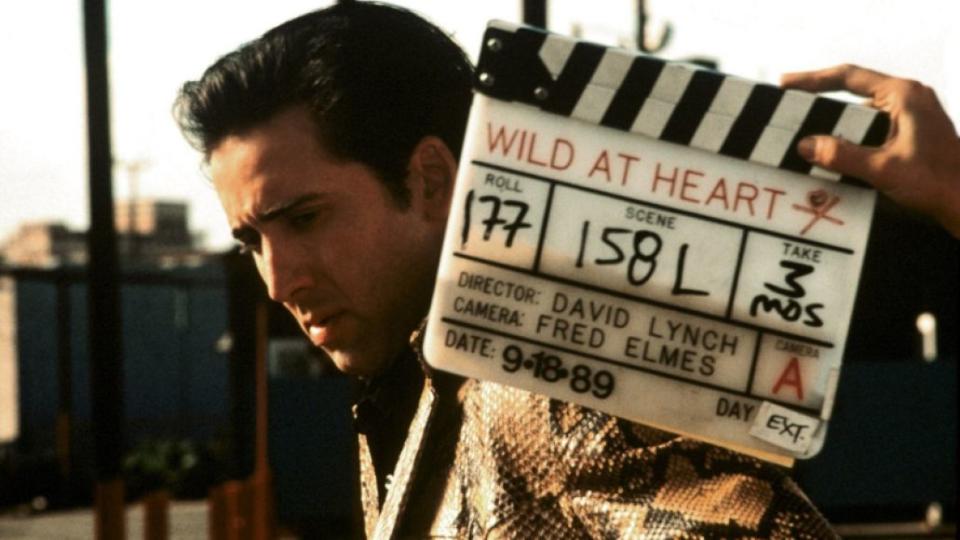

05. Wild at Heart (1990)

Runtime: 2 hr. 5 min.

Cast: Nicolas Cage, Laura Dern, Willem Dafoe, Diane Ladd, J.E. Freeman, Crispin Glover, Harry Dean Stanton, Isabella Rossellini

The Long Pitch: After brutally killing a man in self-defense, Sailor Ripley (Cage) is incarcerated, and wastes no time upon receiving parole before he grabs the love of his life, Lula Fortune (Dern), and hits the road. Together, they run from the law, from the various killers Lula’s mother, Marietta (Ladd), has hired to get rid of Sailor, and from the crushing realization that maybe they can’t just run away forever.

The Short Pitch: Star-crossed lovers light out on the dusty highway to live a life of rebellion, heavy metal, and absolute freedom.

The Elephant Man: Nowadays, a role like Sailor Ripley would seem fairly standard for Nicolas Cage, but in 1990, David Lynch was one of the first filmmakers to figure out a) what a singularly bizarre actor Cage is and b) how willing he would be to explore those now-infamous depths of scenery-gnawing performance in even the most modest roles. Cage is one half of Wild at Heart’s lifeblood, and he gives a marvelously unhinged turn as a creature of impulsive hedonism in a film that utterly celebrates it. It’s the kind of performance that made Cage the cult hero he is at present, and it still ranks high within the actor’s filmography, capturing the actor right at the intersection of his early boyish swagger and his adult mania.

Candy-Colored Clowns: There’s a little bit of Dennis Hopper’s feral creep in Blue Velvet happening within Dafoe’s performance as Bobby Peru, an assassin with hideous teeth and a Peter Lorre mustache, who eventually comes to pursue the film’s central couple. Yet Dafoe makes the villain his own, and Bobby ends up as one of Lynch’s all-time great menaces. Dafoe adopts the tics of an animal, lecherously drooling over Lula and delivering his lines with all the infectious relish that anybody who loves a bit of purposeful vamping will adore. He’s a mangy, hideous creature in every sense, and Dafoe expertly flexes his ability to be charming and unsettling in equal measures at once. He’s a walking horror in a fringed leather jacket.

In Dreams: Wild at Heart is one of Lynch’s less narratively unhinged works, but his editorial penchant for dreamlike cross-fades is on full display here. But instead of aiming for surrealist disorientation, Lynch uses the device to illustrate the breathless passion of youth, draping many of Sailor and Lula’s sexual encounters in a blood-red filter or gazing along a racing highway as they sprint off to nowhere in particular. The film’s most Lynchian setpiece, though, is one in which Sailor and Lula happen across a young woman (Sherilyn Fenn) who’s been involved in a severe car accident and can’t seem to worry about anything but the location of her hairbrush. Though this film and The Straight Story share precious few commonalities, they both trade on the simple eccentricities of everyday people, though the characters here are a far cry from the quaint middle Americans of that later film.

Radiator Songs: If you’re still wondering where Wild at Heart lands on the Cage scale of madness, the film ends with him serenading Lula to the tune of Elvis Presley’s “Love Me Tender.” (The snakeskin jacket was also the actor’s idea, but we digress.) Although Badalamenti is still present with a couple of instrumental suites throughout, Lynch’s soundtrack leans far more on pop hits here. The chilling night drive midway through the film unfolds to the purring, menacing sounds of Chris Isaak’s “Wicked Game”, and Van Morrison and Rubber City are also used to supreme effect. And there are few things more enjoyable in the film than watching Cage and Dern cut loose to the sounds of the speed metal band Powermad’s “Slaughterhouse”.

The Black Lodge: Shot in California, Texas, and Louisiana, Wild at Heart makes more-than-effective use of the vistas of the lone, untamed desert. It’s firmly entrenched in the traditions of iconic road movies, the dive motels and seedy bars that tend to build the worlds in which lone, free people exist. The 1965 Thunderbird functions as its own period-perfect set for the swaggering neo-Bonnie and Clyde at the film’s center, a rolling symbol of everything from Cage’s swaggering masculinity to the “Dead Man’s Curve”-esque sense of doom hanging over the lovers. The locales aren’t as particular as in other Lynch films, but they’re utterly perfect for this specific one.

To Be AD’Ored: Wild at Heart won the 1990 Palme D’Or at the Cannes Film Festival, but the announcement was also accompanied by loud booing at the time. Test audiences walked out of the film, and numerous critics savaged it, as it was very nearly slapped with the dreaded X rating before Lynch agreed to trim down a particularly grisly shotgun blast near the film’s end. While the film eventually came to earn Ladd an Oscar nomination, it’s still among the filmmaker’s more aggressively polarizing works, despite its relatively lucid storytelling.

Lynch on Lynch: To the New York Times in 1990, on the subject of adapting Barry Gifford’s novel: “But you know, you really just try to be true to the material. If an idea takes you to the electric fence of your morality, you don´t try to cross over. Sometimes, though, you don´t know when you´re about to get fried.”

Analysis: Wild at Heart is perhaps Lynch’s loosest, most seemingly relaxed film, which sounds like a stretch given the graphic violence and sex, let alone the rape trauma that comes to factor heavily into its final act. But it’s at once a perverse vision of the American road movie and a feverish celebration of young, irresponsible love.

There’s a reason it’s become a beloved cult item for some: Not only is it defiantly weird in the character-driven Twin Peaks way that Lynch enthusiasts tend to enjoy most, but because underneath all of Lynch’s oddball flourishes is a story about a man who loves a woman, and a woman who loves a man, and their unyielding need to be together. It’s a film in keeping with the heart of American filmmaking tradition, even as it covers it in blood. And to think, this is the tamer version of the film Lynch originally made.

— D.S.M.

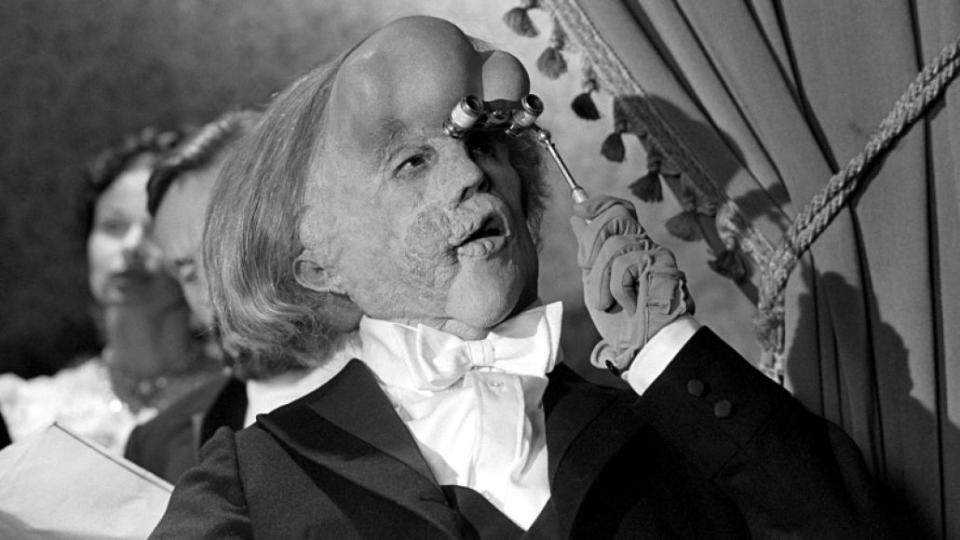

04. The Elephant Man (1980)

Runtime: 2 hr. 4 min.

Cast: Anthony Hopkins, John Hurt, Anne Bancroft, Sir John Gielgud, Wendy Hiller, Michael Elphick, Hannah Gordon and Freddie Jones

The Long Pitch: While visiting a Victorian freak show, London surgeon Frederick Treves encounters John Merrick, a deformed man who’s being held captive and shown to audiences as The Elephant Man. Stunned by Merrick’s medical condition, Treves brings the troubled victim back to the hospital, where he’s both studied and introduced to high society.

The Short Pitch: Lynch tries his hand at a historical biopic and somehow still manages to make out-of-this-world nightmares out of non-fiction.

The Elephant Man: When it came time to cast the titular lead for The Elephant Man, Lynch initially tapped his Eraserhead star Jack Nance for the role, but that “wasn’t in the cards,” according to the filmmaker. Instead, he was introduced to the talents of John Hurt. Now, by the late ’70s, Hurt already had over 20 credits to his name and was coming off of two critical and commercial smashes with 1978’s Midnight Express and 1979’s Alien — the former of which won him a Golden Globe and a BAFTA. So, it’s not as if the world hadn’t heard of the English actor; in fact, after moviegoers witnessed a xenomorph burst out of his chest, it would be impossible not to recognize the guy.

Of course, nobody would with The Elephant Man. Hurt would only be known by name on the poster as he was hidden under eight hours’ worth of makeup, expertly designed from casts of Merrick’s real-life body that have been kept by the Royal London Hospital’s private museum. Despite all the layers, though, Hurt managed to bring some unmistakable humanity to his performance, thanks in part to the maudlin dialogue, but mostly from his physical performance, specifically the way he exhibits feelings of fear, love, and sorrow through movement. Even during times of solitude, you understand what he’s thinking and feeling, and it’s these moments that brought him an Oscar nom.

Candy-Colored Clowns: You kind of have to despise every villain in The Elephant Man, if only because they’re all a bunch of archetypes running around with the words BAD GUY slapped across their forehead (see: Freddie Jones as the incorrigible Mr. Bytes or Michael Elphick as the nasty Night Porter). Much of that has to do with Lynch’s throwback style of filmmaking as he opted to make this film a more classical motion picture, recalling the post-World War II-era productions, whose villains tend to lack the more subtle nuances we’re accustomed to in, say, most films created in the ’60s and beyond. But there’s something to be said of Hopkins’ Dr. Treves and his own personal agenda.

Halfway through, while meditating near the fireplace, Treves asks aloud, “Am I a good man or a bad man?” It’s a fair question and one the film posits on the merits of subjugating anyone to study. What makes Treves different than Bytes? Well, lots of things — for one, he’s not beating the poor guy mercilessly to death — but one might argue he’s similarly parading him around and locking him away from society at night.

Yet what winds up truly separating Treves from monsters like Bytes or Merrick’s many spectators is how the doctor treats his patient like a human being — seriously, Hopkins’ benevolent performance is unforgettable — and it’s that respect that makes Merrick feel like one again.

In Dreams: Rather than adapt the story from its popular stage play, screenwriters Christopher De Vore and Eric Bergren consulted the true-life accounts of Frederick Treves’ The Elephant Man and Other Reminiscences (1923) and the more scientific recollections of Ashley Montagu’s The Elephant Man: A Study in Human Dignity (1971). This explains why the film is a far more straightforward affair and why it’s so easy to pinpoint Lynch’s own contributions to the screenplay. His touch is the loudest in the film’s hallucinatory sequences, when we step into Merrick’s mind and experience his torturous nightmares.

Some of it’s overtly literal — the elephant footage, for example — but it’s really the only time we actually feel Merrick’s inner turmoil. The worst of them all is in the middle of the film as Merrick finds himself in the bowels of some factory, staring up at pipes and over towards muscular, dirty men sweating over giant gears. Elephants roar in the background and smoke billows everywhere as Lynch zeroes in on their defined bodies, which stand in stark contrast to Merrick’s own deformities. It’s a jarring sequence but quite indicative of where Lynch would eventually go years later.

Radiator Songs: We’ll get to Mel Brooks in a minute, but let’s just say his involvement with The Elephant Man motivated a number of decisions behind the scenes. Among them was the hiring of his longtime composer John Morris, who scored, well, basically every one of his films — The Producers, Blazing Saddles, Young Frankenstein, you name it, he tracked it. On paper, it seems like a weird choice to get a guy who scores funny films for a depressing story about the tormented life of Joseph Merrick, but that jovial background no doubt informed him on this production.

Shave off the laughs and what do you get with each Mel Brooks movie? A different genre. Sure, Blazing Saddles and Young Frankenstein came out the same year, but one was a Western and the other a monster movie. In other words, Morris knew how to evolve, and for The Elephant Man, he dug deep into the scenery, capturing the moods of both the dark, damp streets of England and the wicked, eldritch atmosphere of a 19th century carnival. One could argue that without his stirring rendition of “Adagio for Strings”, the film never would have bruised its audiences.

The Black Lodge: When Treves first encounters Merrick at the very beginning of the film, the setting for the Victorian freak show looks like something out of a lucid dream. As Lynch follows Hopkins down the maze-like rows of oddities, most of which are draped in black curtains, the walkway appears to grow narrower with each step. To make matters worse, the number of disturbed spectators increase, adding an extra dose of claustrophobia and a not-so-subconscious layer of tension for what lies ahead. It’s a short scene, and one might say it’s rather negligible compared to something grand like Merrick’s orgasmic first night at the opera, but this writer can’t shake the cold, sequestered feeling that Lynch immediately injects into his film

Produced by BrooksFilms: Have you heard the one about David Lynch, Ronnie Rocket, and Mel Brooks? Okay, well, shortly after Eraserhead came and went, Lynch started floating around the idea of a follow-up titled Ronnie Rocket, which, as he would explain, was “about electricity and a three-foot guy with red hair.” That didn’t fly with studios, but it did catch the eyes and ears of Stuart Cornfield, who really believed in the filmmaker after seeing Eraserhead. Much to his dismay, Cornfield couldn’t get Ronnie Rocket to lift off, so he offered Lynch another script: The Elephant Man. The title won Lynch over, and he quickly agreed to helm the picture, which would be the first production under the BrooksFilms banner.

Brooks wasn’t so much a business partner as he was a total champion of Lynch’s work. When he first screened Eraserhead, he stormed out of the theater and hugged Lynch, who had been waiting outside, screaming: “You’re a madman, I love you! You’re in.” Naturally, this made production on The Elephant Man something of a breeze, especially when the big whigs at Paramount, who distributed the film in the States, were reluctant to include the more bizarre dream sequences that bookended the film. But Brooks, ever the madman himself, would write them off as idiots, arguing that they didn’t understand Lynch’s genius, and, well, they simply abided. Years later, David Cronenberg would experience similar magic.

Outstanding Achievement in Makeup: When An American Werewolf in London won Outstanding Achievement in Makeup at the 54th Academy Awards in 1982, Rick Baker probably should have thanked the fine, underrated work of Christopher Tucker. Why? Let’s just say if it wasn’t for Tucker’s imaginative talents behind the scenes of The Elephant Man, nobody would have complained about the film being unrecognized for his efforts, and there probably wouldn’t have been a category to win at the Oscars until a few years later. Or, you know, after Werewolf if things still hadn’t progressed. It’s cool, though, seeing as Tucker would take home the gold a couple years later for 1983’s Quest for Fire. #vindicated

Lynch on Lynch: “I’ll tell you what kept me going, and that was pretty much John Merrick — the character of the elephant man. He was such a strange, wonderful, innocent guy. That was it. That’s what the whole thing’s about. And then the Industrial Revolution. Or you see pictures of explosions — big explosions — they always reminded me of these papillomatous growths on John Merrick’s body. They were like slow explosions. And they started erupting from the bone.

“I’m not sure what started the explosion, but even the bones were exploding, getting the same texture, and it would come out through the skin and make these growths that were slow explosions. So the idea of these smokestacks and soot and industry next to this flesh was also a thing that got me going. Human beings are like little factories. They turn out so many little products. The idea of something growing inside, and all these fluids, and timings and changes, and all these chemicals somehow capturing life, and coming out and splitting off and turning into another thing … it’s unbelievable.”

Analysis: Lynch’s thoughts are telling. Not only do they reveal some key insights into the filmmaker, namely how he’s able to find a diamond in a pile of rocks, but also how he writes his own signature. At face value, The Elephant Man doesn’t appear to belong to Lynch — after all, the screenplay floated through dozens of hands before finally landing into his — but you’d be a fool to say it’s a studio job. Because without his Lynchian motifs, the film would be little more than a boilerplate historical drama, one that would swell with stellar performances and production values, but lack the emotional malaise that allows audiences to connect with a subject so distant and so tortured. That’s what Mel saw in Lynch, and that’s what we all see in Lynch today.

— M.R.

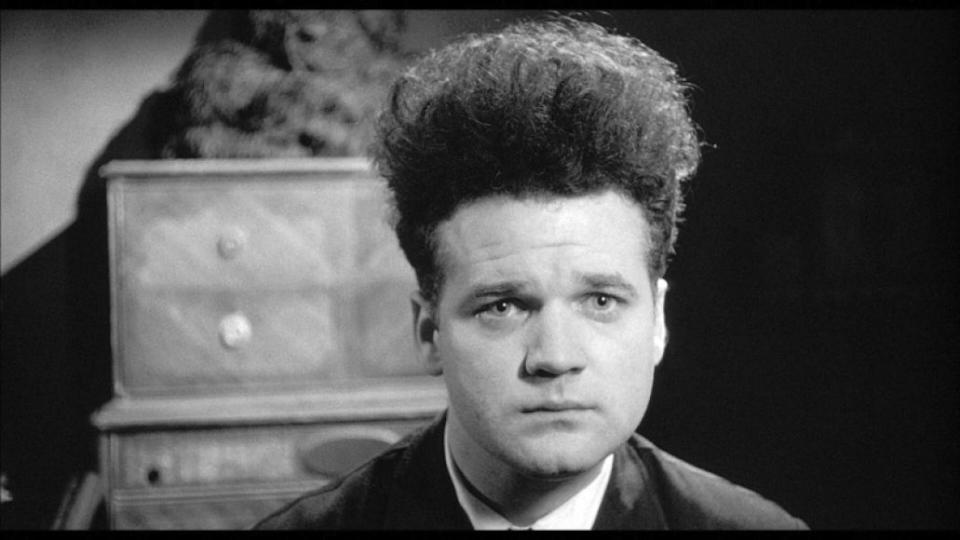

03. Eraserhead (1977)

Runtime: 1 hr. 22 min.

Cast: Jack Nance, Charlotte Stewart, Judith Roberts, Jack Fisk, Laurel Near, a monstrous baby, many of your nightmares

The Long Pitch: Great-haired Henry Spencer works at a factory in a post-apocalyptic industrial wasteland. His girlfriend gave birth to a deformed baby, then skips out, leaving Henry to care for the constantly crying monster. Also, there’s a “Man in the Planet,” a lady in the radiator, and his head gets turned into erasers. Hilarity ensues. Oh wait, I meant anxiety ensues.

The Short Pitch: David Lynch takes the grotesque body horror surreality of his shorts to a full-length and doles out nightmares and existential conversations in equal dose.

The Elephant Man: Before meeting David Lynch, Jack Nance worked with the American Conservatory Theater in San Fransisco, taking small roles like “gardener” in an episode of Columbo. But upon the young actor and the aspiring director becoming friends, Nance found the role of a lifetime as Henry Spencer. Even if you’ve only seen the poster for the film, Nance’s eager stare and massive hair will be immediately familiar. Any self-respecting art kid will have seen Eraserhead in college, or at least have pretended to. Lynch’s film made Nance an icon, and Nance’s shoulders-up anxiety and fear are the human core of the surreal nightmare.

In Dreams: Eraserhead is a nightmare, dreams within dreams, careening from surreal moment to surreal moment. Running down a scene list scans like reading the dream journal of a disturbed person, plot lines nearly impossible to pick out from the tangle of interweaving themes and symbols.

But the most surreal presence, the one that incites and upsets whatever little order there is in this world, is the baby. Its introduction into the film is a flashpoint, a visceral burst of pain and suffering. It looks mutated, slick and raw as if a few layers of skin had been peeled away. It’s phallic, sperm-like, fetal, producing a low-grade wail that persists throughout the film. Its eyes, mouth, and neck move independently, far too fluid to be anything but biological.

Lynch has explained at various points that “it was born nearby” or “maybe it was found.” Whether he dug up a half-buried, small mammal carcass or just constructed a child out of non-organic materials, the result is an unsettling bit of body horror.

Radiator Songs: As much as “In Heaven (Lady in the Radiator Song)” has become the prototypical Lynchian music moment — a delightfully simple song presented in the most surreal possible way — the true depth in the film’s soundtrack comes in the industrial whine and grind that never seems to halt. The mechanic noise scrubs at your brain, simultaneously pushing away your ability to connect with anything on screen while tying the strange moments all together. Factory sounds, dogs barking, creaking, booming, clanking — and a little bit of Fats Waller’s organ. It’s ambient music, though without any of the zen vibes that that term typically comes with.

The Black Lodge: David Lynch has a conflicted relationship with family and home. Throughout his oeuvre, homes, the place where things are supposed to be safe and happy, consistently are the places where serious pain, trauma, and struggle occur. That’s certainly the case in Eraserhead. Similar to how there’s no single top surreal moment, it’s hard to say there’s a most intriguingly designed set; as a trained visual artist, Lynch came to this film with the goal of meticulously designing every inch. As a fictional version of reality, he took that full reign to craft the meaning and look of every single square inch within the film’s frame.

The most upsetting aspect of that craftsmanship, then, is the way in which he portrays the X family home. There’s nothing all that twisted about their apartment — it’s a shabby, but not entirely unrealistic take on a ’50s-ish apartment. It’s minimally furnished, leaving plenty of space for all the dread and panic of the soundtrack and the insanity of the characters to fill. The dark shadows and flickering lights make the normalcy that much more abnormal. By making the place look so plain, he reveals the darkness inherent within it.

Just Cut Them Up Like Regular Chickens: This is, perhaps, the strangest David Lynch film, and as such it has led to endless criticism and analysis. There are symbols and themes galore — adultery, sexuality, technology, industrialism — if you’re looking for them. And if you’re not, if you just want to go along for the eerie ride, there’s some “enjoyment” in that, too.

Lynch on Lynch: “Eraserhead is my most spiritual movie. No one understands when I say that, but it is.”

Analysis: A few years after directing this one, Lynch was being discussed as the potential director of a Star Wars movie. Go watch a few minutes of Eraserhead again, and then let that sink in for a moment. But then the movie inspired artists from Tom Waits to Mel Brooks to Stanley Kubrick and continues to be a touchstone for those who give sidelong looks at reality the world over.

This is also peak Lynch, the artist on his own with only a small circle of close collaborators, unaffected by mass expectations or business demands — well, at least beyond those of the day jobs the cast and crew took to keep funding going. Much like the spermatozoic creature that floats out of Henry’s mouth at the beginning of the film, this project seems pulled out of the darkest recesses of Lynch’s mind, refusing to compromise or explain itself. It bears repeated viewings, only unfolding more and stranger thoughts, feelings, and analyses.

— A.K.

02. Mulholland Drive (2001)

Runtime: 2 hr. 27 min.

Cast: Naomi Watts, Laura Elena Harring, Justin Theroux, Dan Hedaya, Ann Miller, Rebekah Del Rio, Billy Ray Cyrus

The Long Pitch: Welcome to the seedy underbelly of Hollywood, as seen through a young ingénue (Watts) who arrives in town ready to make her fame, only to find herself entangled with a woman suffering from amnesia (Harring), romantically and emotionally and otherwise. Elsewhere, seemingly disconnected vignettes explore various nightmarish scenarios, as the two women’s lives become more and more entwined.

The Short Pitch: Lynch invites you to wander around the nightmarish subconscious to the point of absolute disorientation and draw your own conclusions.

The Elephant Man: Oh, take your pick. Mulholland Drive is rife with unusual casting choices, from references to old Hollywood to some genuinely strange faces. The team of Dan Hedaya and Angelo Badalamenti, as the nightmarish studio (or mob?) heavies who force Theroux’s filmmaker into casting Camilla, cut an unnerving profile, and Badalamenti as a presence within the film is a nice in-joke unto itself.

Maybe it’s Billy Ray Cyrus, as the unreasonably placid lover Theroux finds at home with his wife. But it’s Ann Miller, who plays Coco, who has the most lineage; Miller was herself a starlet in the ‘40s and ‘50s, who largely fell out of Hollywood in her later years save for her appearance here. It would prove to be her last performance, as she passed away a few years after the film was released.

Candy-Colored Clowns: Let’s talk about the man with the face for a moment. One of Mulholland Drive’s more unsettling scenes, and easily one of the more heavily debated, is the unnerving sequence early on in which a man recounts a dream taking place inside the very Winkie’s they’re eating in at the moment, which ends in a horrific encounter with some sort of spectral creature. They then end up wandering outside, the being surfaces, and the man appears to have a heart attack from the shock of the dream.

It’s an interesting microcosm of the film as a whole; Lynch’s greatest villain is the temporal disorientation of dreams and the monsters they can find. Sure, there may (or may not) be mobsters and such lurking about, but Mulholland’s most lasting fright is the creeping dread that it conjures from early on. And those old people at the end, though a hallucination, are just a terror to look at. The brief scene of them smiling inhumanly, early in the film, verges on nauseating.

In Dreams: Depending on what interpretation you might subscribe to, there’s a case to be made for the entirety of Mulholland Drive as some kind of feverish dream; after all, one of the film’s first images is an unseen presence wandering down, deep into a pillow. But, from the opening moments with that hallucinatory dance sequence, the film offers an endless litany of memorable dreamlike sequences.

For now, we’ll linger on the entirety of the “Silencio” scenes in the theater, in which Betty and Rita (well, maybe) end up driven to a late-night cabaret of some kind, one that takes on the tone and presence of a nightmare from which one cannot be shaken awake. Rebekah Del Rio’s performance of “Llorando” is one of the film’s most memorable moments, but the repetitions (“No hay banda”), Watts’ shaking fit, and the sense that something inexplicable but horrifying is happening are what truly tie the scene together.

Radiator Songs: Badalamenti’s work here are some of the more well-regarded compositions of his career and for good reason. In keeping with the film’s loose narrative trajectory, Badalamenti has described the experimental process through which the score came together: “I gave David multiple music tracks, which we call ‘firewood.’ I’d go into the studio, and record these long 10- to 12-minute cues with a full orchestra. Sometimes I’d add synthesizers to them. I’d vary the range of the notes, then layer these musical pieces together. All would be at a slow tempo. Then David would take this stuff like it was firewood, and he’d experiment with it.”

The resulting soundscape is more concerned with atmosphere and hard-to-articulate tones much of the time, though there are also flecks of bebop and older pop that appear throughout. The most resonant piece, though, is the three-note swell that accompanies the rise and fall of Betty and Rita’s relationship, at once lightly dissonant and wrenching. It’s the kind of piece that’ll bring a tear to your eye and then immediately send you wondering exactly why this has happened at all.

The Black Lodge: The theater hosting the late-night performance is just one of the film’s iconic set pieces, but the choices are endless: Winkie’s Diner, the room with the microphone and the chair, the apartment, that rounded bend either on or near Mulholland Drive. Lynch’s set design is integral to the film’s pervasive sense that not all is as it seems, or possibly existent at all. In one sense, the film’s locations only bolster Lynch’s long-running fascination with the trappings of bygone, mid-century Americana, particularly as it relates to the glitzy, old-fashioned film industry, and in another it perverts those locations, robbing them of their glamour and innocence to reveal something far more sinister beneath.

10 Clues: When the film was released on DVD, Lynch famously included a list of 10 clues that could help people decipher it. Could be misdirection, could be the secrets of the universe. Nobody’s all that sure. Those are as follows:

01. Pay particular attention in the beginning of the film; at least two clues are revealed before the credits.

02. Notice appearances of the red lampshade.

03. Can you hear the title of the film that Adam Kesher is auditioning actresses for? Is it mentioned again?

04. An accident is a terrible event…notice the location of the accident.

05. Who gives a key, and why?

06. Notice the robe, the ashtray, the coffee cup.

07. What is felt, realized and gathered at the club Silencio?

08. Did talent alone help Camilla?

09. Note the occurrences surrounding the man behind Winkles.

10. Where is Aunt Ruth?

Lynch on Lynch: On the value of mysteries, as it relates to the film: “A mystery is one of the most beautiful things in the world. It pulls you into the world, and the ideas have a way of putting in clues. They’re not spoon-fed to you, but they’re there. All you have to do is pay attention, and use your intuition.”

Analysis: Mulholland Drive is a mystery that people still find puzzling, and that likely won’t change for years to come. Lynch’s staunch refusal to offer any singular interpretation of the film renders it as something any viewer can impress their own understandings onto — like so many other great works of art. Any talk of logic and through-lines, albeit helpful in attempting to parse the film out in written form, is beside the point after a while … and that’s by design.

Mulholland Drive is a sensory thing, a film that also transcends the medium in its willingness to abandon all familiarity and dig around in what could be the subconscious, or hell, or anything else you may be able to bring to the film. It’s a Hollywood tragedy in the old tradition, but one completely born of a disoriented, unsettled world. And it’s one of those rare, incredible films that actually returns some meaning to the phrase “it’s like nothing else you’ve ever seen.” Because in this case, you truly haven’t.

— D.S.M.

01. Blue Velvet (1986)

Runtime: 2 hr.

Cast: Kyle MacLachlan, Isabella Rossellini, Dennis Hopper, Laura Dern, Hope Lange, George Dickerson, Dean Stockwell

The Long Pitch: After his father suffers a near-fatal stroke, college boy Jeffrey Beaumont returns home to the seemingly pleasant confines of Lumberton, North Carolina. When he stumbles upon a severed ear in his neighborhood, curiosity gets the best of him, and he slowly succumbs to a downward spiral of lust, deviancy, and obsession.

The Short Pitch: Yep, this is the one where “the bad guy from Speed” huffs gas and screams, “Baby wants to fuck!” like a raving lunatic.

The Elephant Women: It’s hard to believe now, but Isabella Rossellini and Laura Dern were a couple of no-names back in the mid-’80s. Fortunately for them, however, they’ve always been well connected to Hollywood; Rossellini is the daughter of actress Ingrid Bergman and Italian film director Roberto Rossellini, while Dern is the daughter to veteran actors Bruce Dern and Diane Ladd. For Blue Velvet, one might argue Rossellini had the tallest order of the two, playing Dorothy Vallens, a mentally disturbed and physically battered mother who also represents a pinnacle of sexuality for the film’s principal characters.

That’s not to dismiss Dern’s performance; she absolutely shines as Sandy Williams, the beautiful girl-next-door and handy partner-in-crime to Kyle MacLachlan’s Jeffrey. In a rather poetic twist, both actresses go H.A.M. together in the same scene, specifically when the shit hits the fan outside the Williams household. “Your seed is in me,” a naked Dorothy tells Jeffrey, and everything just crumbles all at once. Oddly enough, this bizarre sequence was actually inspired by a real-life experience of Lynch’s, who as a child once witnessed a naked woman strolling down his neighborhood late at night. Spooky.

Candy-Colored Clowns: Technically, there are two. After all, few will deny the power and magnetism of Dean Stockwell’s elusive crime patriarch, Ben. When he sings Roy Orbison’s “In Dreams”, illuminated by a glowing trouble light, the film stands still with its accompanying characters, floating into a mercury dream that’s horrifying yet eerily enchanting. At face value, Ben is something of a charmer, what with his coifed hair and well-manicured look, but he’s truly a pillar of deceiving beauty. And it’s the subtlety of his character, the little cracks and tears, that make him so stirring and alluring.

But c’mon, there’s no arguing over Dennis Hopper’s dickhead ganglord, Frank Booth. He’s manic, he’s impulsive, he’s unpredictable in every sense of the word. When he’s not huffing and sucking on unidentifiable gas, he’s ricocheting across the room, spouting off at others with vitriolic rage. Here are a few velvety slices: “Suave! Goddamn you’re one suave fucker!”; “Don’t toast to my health, toast to my fuck!”; and “Fuck you, you fucking fuck!” What an asshole, right? Of course, but he’s one of the silver screen’s greatest assholes ever, a huggable psychopath that’s impossible to ignore.

In Dreams: Save for The Straight Story, and maybe The Elephant Man, Blue Velvet is actually the most grounded film in Lynch’s oeuvre. Almost immediately, you get the sense that this could be Anywhere, U.S.A, and that’s sort of the point. The filmmaker wants you to be able to relate to the proceedings, which is why the more surrealist portraits here tend to hit the hardest.

One of the more tangible examples is the way Lynch takes traditionally comfortable locales and subverts them into nightmares, from the living room where Jeffrey witnesses Frank “seduce” Dorothy, to the neighborhood lounge that leads to hell, and to the front lawn that’s marred in tragedy. All of this culminates with the grand finale, where Anywhere, U.S.A. looks like Anywhere, U.S.A. but something is now off … it’s almost mechanical. You start to wonder, Has it always been like this?

Radiator Songs: Blue Velvet marked the first time Lynch worked with now-longtime collaborator Angelo Badalamenti, and it was all due to happenstance. During pre-production, Rossellini had been struggling to make her performance of “Blue Velvet” work for Lynch, and it was only when producer Fred Caruso recommended his pal Badalamenti that things started clicking. The composer came in, worked with the actress, and solved the film’s predicament within hours. Stunned, Lynch opted to work more with Badalamenti, and the two collaborated on another song titled, “Mysteries of Love”, which Julee Cruise would sing. Shortly after, the filmmaker insisted that Badalamenti score the film, referencing Soviet composer Dmitri Shostakovich as an influence.

What came to fruition was a dense arrangement of classical compositions with hints of modern pop — think the ominous undertones of Bernard Herrmann meets the dramatic textures of Ennio Morricone with a dollop of Brian Eno’s night sky glaze. At times, the score sounds sweeping (“Main Title”) and romantic (“Mysteries of Love”), but often it’s dangerous (“Night Streets”) and paranoid (“Jeffrey’s Dark Side”).

Beneath the surface, there’s this jazzy wash, playing to the film’s neo-noir aesthetic, which would become a trademark of Badalamenti’s as he would later prove on Twin Peaks. Tossed in with Roy Orbison and Julee Cruise, the soundtrack assists in making the film feel very out of time, stuck between the pleasantries of the ’50s and the banalities of a questionable present.

The Black Lodge: Everything’s par for the course in Blue Velvet, except, well, Ben’s curious hideout. When Frank kidnaps Jeffrey and takes him outside of town to his leader’s apartment, what lies within can best be described as abnormal. Lynch’s production design here prods the mind with so many aching questions, from “Who the hell are the portly middle-aged ladies on the couch?” to “What are they doing to Dorothy’s children?” to “Why would anyone ever want to hang out here?”

It’s so rugged and simple, but it’s a jarring distraction from the smooth Americana we’ve been privy to for the last 40-something minutes. So, when you’re ripped right out of the scene, you feel just as bewildered and terrified as Jeffrey, and you’ll never get any answers to your questions. You’re simply haunted.

The Critics’ Choice: When Blue Velvet touched down in 1986, the film was praised by critics and scholars. Gene Siskel thought it was one of the best films of the year — though, his onscreen pal, Roger Ebert, despised it — and The New York Times dubbed it an “instant classic.” Such praise led to multiple accolades, including Lynch’s second Oscar nomination for Best Director, and the film would go on to sweep the Boston Society of Film Critics and the National Society of Film Critics (both for Best Film, Director, Cinematography, and Supporting Actor for Hopper).

In a more personal triumph, Rossellini would win an Independent Spirit Award for the Best Female Lead, opening the door for several dramatic roles to come. Over the years, Blue Velvet has since gone on to feature in multiple Best Of lists from AFI, Variety, Sight & Sound, Total Film, Entertainment Weekly, and more.

Lana Del Valens: In 2012, singer Lana Del Rey covered the infamous title track for an H&M endorsement. In the accompanying music video, she assumes the role of Dorothy Valens, a not-so-subtle wink that eventually caught the eye of Lynch, who gave his thumbs up, saying: “Lana Del Rey, she’s got some fantastic charisma and — this is a very interesting thing — it’s like she’s born out of another time. She’s got something that’s very appealing to people. And I didn’t know she was influenced by me!”

Lynch on Lynch: “This is the way America is to me. There’s a very innocent, naive quality to life, and there’s a horror and a sickness as well. It’s everything. Blue Velvet is a very American movie. The look of it was inspired by my childhood in Spokane, Washington. Lumberton is a real name; there are many Lumbertons in America.”

Analysis: From infinite sidewalks to dark nightclubs, cramped closets to tortured dreams, this disturbing coming-of-age film offers the true synthesis of David Lynch. It’s a timeless, if not sordid, masterpiece that never gets lost in its own madness, capturing the filmmaker at his most focused and vital.

It’s also an exercise for the mind: As Jeffrey slowly unravels this macabre mystery, we’re similarly confronted by our own dreadful, existential quandaries and urged to chew on the fact that we’re all voyeurs, we’re all primal beasts, and we’re all illusionists. The real horror is how we’re able to live with ourselves after knowing such things, and if that’s not a terrifying realization, then that only adds further weight to the keen insight of Blue Velvet.

— M.R.

A Definitive Ranking of David Lynch’s Movies

Consequence Staff

Popular Posts