‘Ets’ was a brilliant biologist, skilled outdoorsman and zany pal | Sam Venable

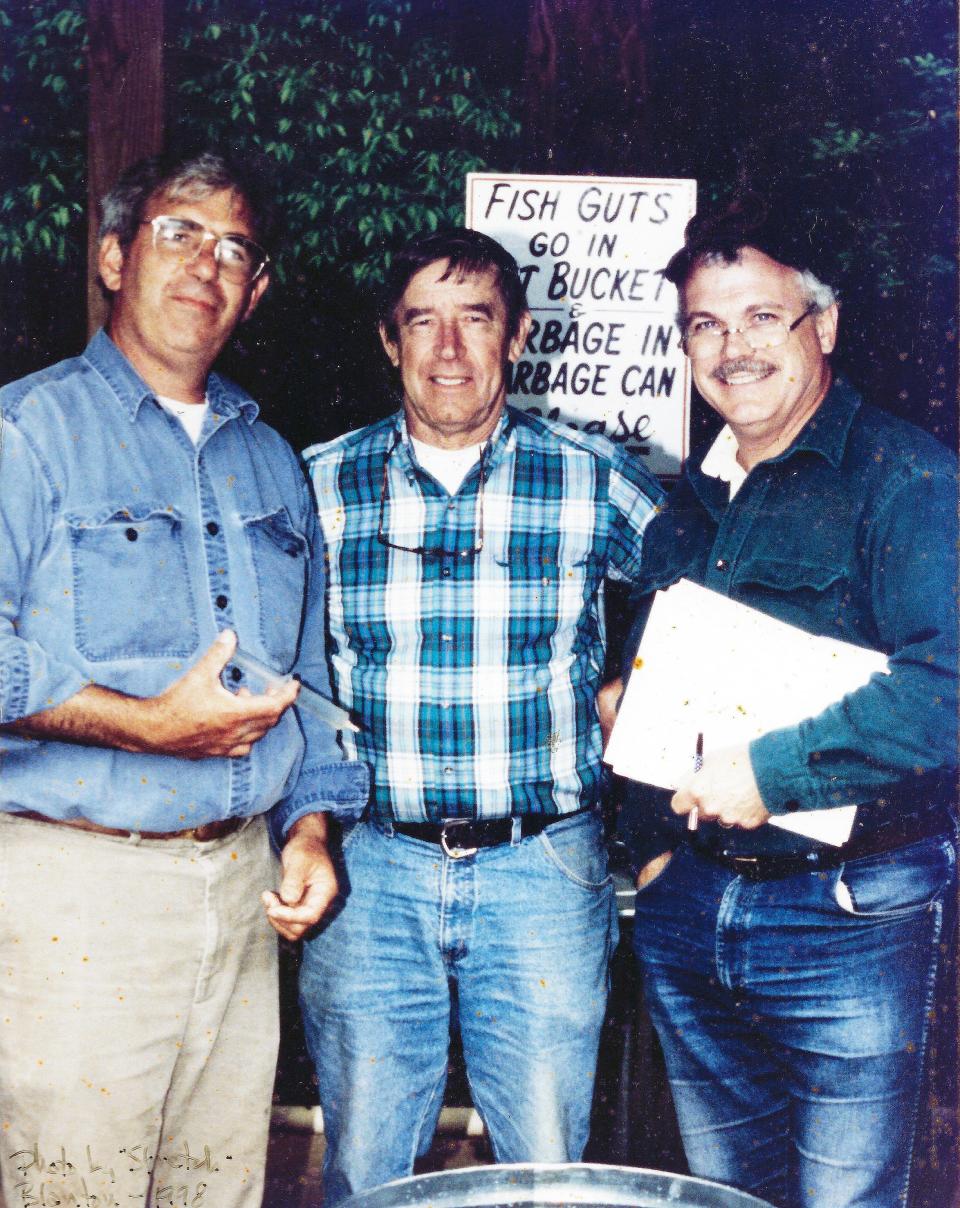

News Sentinel columnist Sam Venable shared a 50-year friendship with Dr. David A. Etnier, renowned aquatic biologist, environmentalist, researcher and University of Tennessee professor who died May 17 at age 84. Herewith, a few of Venable’s memories, along with those of others who enjoyed Etnier’s passion for the outdoors and — perhaps even more important — his delightfully quirky life.

What if one of your weekend golfing buddies was Tiger Woods? Or Peyton Manning quarterbacked your rec-league football team? Or Bruce Springsteen occasionally jammed with your garage band?

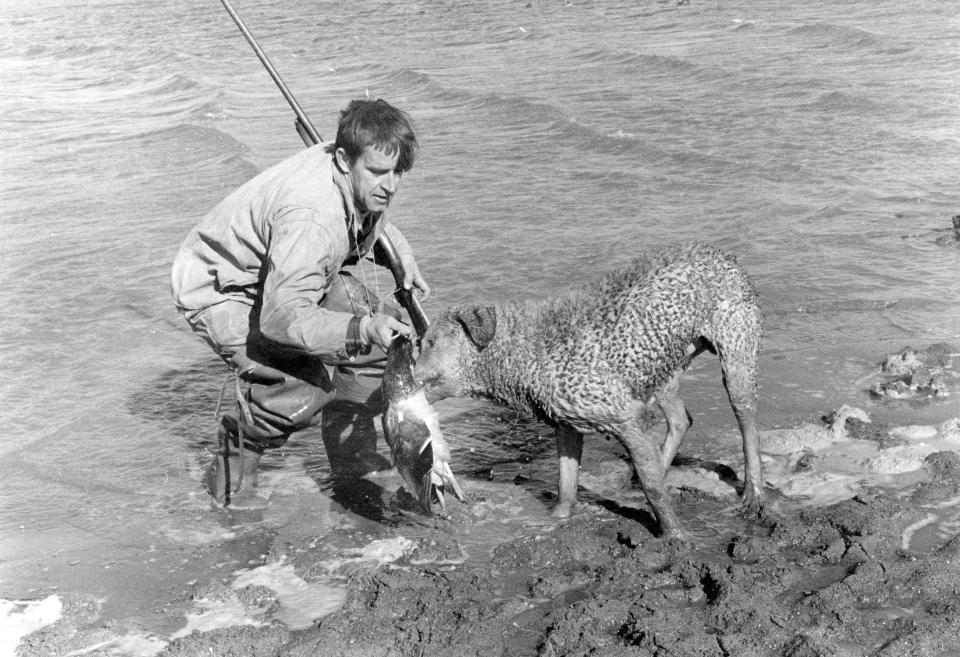

That’s what it was like to share a boat or traipse the fields, forests and wetlands with Dave Etnier. Except for one thing: Not once did hordes of groupies swoop in, begging for autographs and selfies. To 99% of the people he encountered, Etnier — or “Ets” to students, colleagues and friends — was just another guy with a fishing rod, shotgun, chest waders, dip net or binoculars.

But make no mistake. In the world of natural sciences, Ets was a superstar. Trust me on this. The mention of his name in the right audience perked ears, turned heads and started a buzz of excitement.

In the physical sense, Ets left us two months ago. Mentally, his brilliant mind had been ebbing for half a dozen years as Alzheimer’s took its savage toll.

The complete naturalist package

But long before that, Ets was the complete naturalist package. Coldwater fish, warmwater fish, mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians, mussels, mushrooms, trees, insects, whatever. If it grew or flew, crawled or climbed, slithered or swam, he commanded instant recall of its name and its niche in the complex tapestry of nature. If asked, he shared this abundance of knowledge freely and easily, with never a hint of “professorese.”

A Minnesota native, Ets came to UT in 1965, fresh from receiving his Ph.D. For the next 35 years, between teaching and researching, he helped build Tennessee’s zoology program into what’s now the stellar Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology. He established UT’s expansive inventory of fish and caddis fly specimens, later named the Etnier Ichthyological Collection in his honor.

Ah, yes. Honors. Where to begin?

A lifetime of honors

Etnier authored or co-authored more than 70 scientific papers. Described and named 22 new-to-science species of animals, the most notable of which was the snail darter (Percina tanasi) whose fight for survival was successfully argued before the U.S. Supreme Court. Co-authored a voluminous go-to book, “The Fishes of Tennessee.” Had nine newly discovered species of animals named in his honor by admiring colleagues around the country.

Received the U.S. Interior Department’s Fish and Wildlife Service lifetime achievement award. Was posthumously named “Water Conservationist of the Year” by the Tennessee Wildlife Federation.

'I’m starting to feel a wave of irresponsibility wash over me'

Despite that workload, Ets always made time for recreation. “I’m starting to feel a wave of irresponsibility wash over me,” he’d chuckle when telephoning to propose an adventure.Here was a skilled — yet laid-back and laughing — bridge, basketball and tennis player; also a hunter, angler and birdwatcher whose lengthy “life list” of avian identifications was authenticated by sight and call.

Ets excelled in the field by talent, not fancy equipment. For years, former graduate student Gerry Dinkins and I have laughed at this juxtaposition.

Ets was comfortable with reels that squeaked, boats that leaked, rods absent the occasional line guide, banged-up lures from the Eisenhower era, and a repeating shotgun so rusty and caked with mud it grated audibly when pumped. No matter. Ets, ho-hum, invariably caught the biggest fish and slew the most ducks.

I was along one of the few times he got skunked. This occurred during the frigid winter of 1976-77, when Fort Loudoun Lake froze bank-to-bank.

A lesson in ice-fishing

Having grown up in Minnesota, Ets considered East Tennessee the tropics. He was impervious to cold. I never once saw him in a hat. On one particularly bitter, snowy afternoon at Cherokee Lake, he did wear a glove — “a” glove, you understand. He said he’d lost the mate years earlier and never bothered to replace it.

Some of Ets’ fondest Minnesota memories involved ice-fishing. He usually did it bare-handed, according to Liz, his wife of 60 years. “I’ve seen him come in for a bite to eat, and his hands would be bleeding,” she once told me. “He’d warm up, then he’d go right back out.”

Such thoughts were foremost in my mind the arctic morning he summoned me to Choto Marina for a tutorial. For six hours, we chiseled holes in 5-inch ice — yes, he scooped out the slush with ruddy, chapped hands — and dunked minnows for crappies. We caught zilch. However, during my initiation to this insane activity, I did discover, and appreciate, the link between frozen water and firewater.

Like the animals he studied, Ets was an opportunistic eater. If food was available, he gorged. If not, his growling belly was little more than a nuisance. I was present when he nearly bankrupted a Knoxville seafood restaurant on all-you-can-eat night. Conversely, if conditions afield dictated little more fuel than an apple or a wedge of cheese and a handful of sunflower seeds, no big deal.

Even if opportunity knocked at an odd time, he knew how to respond. Who else but Ets would pick and dress a freshly killed mallard at lakeside, fire-roast it on a stick in the woods behind the duck blind, and gnaw it to the bones? I was a witness.

The 'Dead Animal Party'

“You don’t really know an animal until you’ve eaten it,” Ets always quipped when announcing his annual “Dead Animal Party” for graduate students. No wild meat was off limits. Donors were required to list their entrees by scientific name. Unlettered guests, and we know who we are, were permitted to use common names.

Over the years, featured dishes at this event ranged from “road-killed gray fox” to “four and twenty blackbirds baked in a pie.” To reiterate: I was a witness.

Yet even the man who never met a critter he wouldn’t eat sometimes tasted defeat.Longtime Knoxvillians may remember when Etnier’s scholarly exploits were featured on WBIR’s “Heartland” series. For one non-academic show, however, host Bill Landry suggested they gather some of the most slimy, odiferous local fish, like gizzard shad and river herring, and have them exquisitely prepared by a chef. It bombed.

As Landry later recalled: “Even Ets agreed they were too bony and tasted like (s-word).”

Did this affable scientist occasionally comport himself like the stereotypic absent-minded professor? Heavens, yes.

Gerry Dinkins remembers the day he and Ets were driving to a social function in Townsend. For once, Ets was wearing slacks instead of jeans. Glancing at a nearby field, he espied numerous “mud chimneys” made by terrestrial crayfish.

Nothing would do for the ol’ prof than stop the car, walk into the field, recline on his side beside several chimneys, trowel with one hand until he was armpit deep and — hardly flinching when his fingers encountered pinchers — collect specimens for the lab.

Said Dinkins: “When we finally got to the event, his clothes were drenched and covered with mud. Nobody was surprised, though. They all knew Ets.”

Ets’ eccentric humor knew no bounds. Consider:

The 'Noogemobile'

Once on an out-of-state trip, he noticed a random license plate: NUJ 100. For reasons known only to Ets, “nooge-one-hundred” struck his funny bone. Plus, he reasoned, it would be easy to remember. So the next time his Tennessee plate cycled around for renewal, he paid the “vanity” rate for NUJ 100 and re-upped it every year thereafter. The “Noogemobile” was born.

Then there was the time he was walking across the parking lot near his lab and found a dead bird on the pavement. A golden-crowned kinglet, if memory serves, surely the victim of a windshield collision. He picked it up. Hmmm … .

Ets was an amateur taxidermist. He mounted it, upside down, on a perch inside an antique bird cage in his living room. For years, it served as a delightful ruse for the young Etnier children — Jenny, Shelly and Michael (all now Ph.D.s in their own right, by the way.) Any time a visitor saw the dead bird and inquired, that was the kids’ cue to burst into faux weeping about the “sudden” loss of their “pet.” Clearly, smarts and bizarre levity are wrapped in the DNA.

The boat ramp story

But by far, the Etnier story destined to go down in the annals of outdoor history occurred the winter day he drove to Jefferson County to hunt ducks on Douglas Lake.

His only companion was Buck, his pony-sized Chesapeake Bay retriever. Well before daylight, Ets backed down the long, steep ramp at Dandridge Bridge, exited his vehicle, untied the boat, loaded his gear, and prepared to launch.

“Launch” is an all-inclusive word in this regard.

Apparently Ets hadn’t securely engaged the “parking brake.” Sometimes this was a cinderblock, sometimes a chunk of driftwood. At the worst possible moment, the “brake” abruptly failed, and his entire armada — from the VW van’s front bumper to the stern of a 14-foot Aluma-Craft and 20-horse Johnson — went south. “Ploosh,” straight down.

It was only a minor inconvenience.

Free from the trailer, the boat remained afloat. So Ets waded out and grabbed it, climbed aboard, whistled to Buck, and motored downstream to the Muddy Creek embayment and his morning mission with mallards.

Sometime after sunrise, police received the report of a possible drowning at Dandridge Bridge. An officer was dispatched. He surveyed the scene and summoned a long-cabled wrecker. Once the dripping mess was hauled ashore, cops ran a trace of the license plate and hesitantly called his residence with fearful news.

Liz Etnier wasn’t fazed. After listening to the officer’s story, she calmly asked, “Was the boat gone? Was a big brown dog running around on the bank?”

Yes and no, respectively.

“That’s my husband. He’s duck hunting. He’ll be back in a while.”

Which, of course, he was. And although I wasn’t there to witness it, I’ll guarantee Ets kept that tow truck driver in stitches all the way back to Knoxville. Quite likely tipped him with a couple of hastily picked birds (albeit unroasted) from the morning’s bounty.

This October, alongside the Holston River, there will be a gathering of white collars, blue collars, camo collars and no collars who knew and loved David Etnier. The boat ramp story, and dozens like it, will be riotously revisited. There will be tears of sadness and of nostalgic laughter. Also a cup or two lifted in his memory. Meh, maybe three or more, considering this is for Ets.

Farewell, dear old friend. Save me a seat in the boat.

Sam Venable’s column appears every Sunday. Contact him at sam.venable@outlook.com.

This article originally appeared on Knoxville News Sentinel: Sam Venable: ‘Ets’ was a brilliant biologist, skilled outdoorsman and zany pal