In an era of book banning, new book 'Read Dangerously' an impassioned call to do just that

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

It’s hard to believe we live in a time when books are routinely banned in the U.S., removed from library shelves and sent someplace where they can’t influence impressionable young minds. Then again, blockading ideas is one sure way to keep the totalitarian fires burning, and limiting access to books will always limit access to ideas as well.

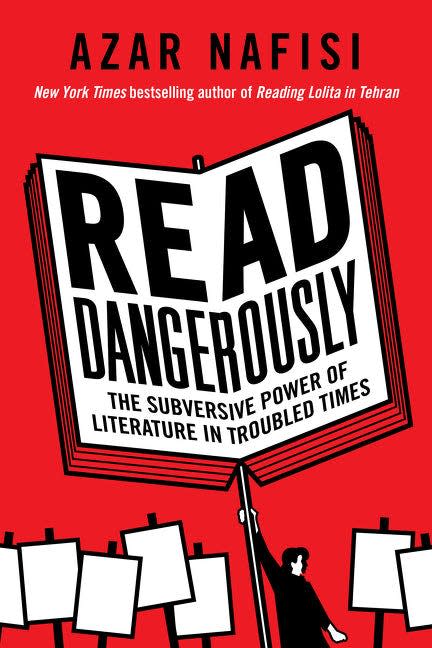

To read, as Azar Nafisi explains so passionately in her new book “Read Dangerously: The Subversive Power of Literature in Troubled Times” (Dey Street Books, 240 pp., ★★★★ out of four, out now), is to take steps toward freedom – freedom of thought, freedom of identity and, yes, political freedom.

“Reading does not necessarily lead to direct political action,” Nafisi writes, “but it fosters a mindset that questions and doubts; that is not content with the establishment or the established. Fiction arouses our curiosity, and it is this curiosity, this restlessness, this desire to know that makes writing and reading so dangerous.”

They're trying to ban 'Maus': Why you should read it and these 30 other challenged books

Now based in Washington, D.C., Nafisi, best known as the author of “Reading Lolita in Tehran,” knows a thing or two about literature and oppression. She grew up in Iran, reading and writing as a means of empowering herself and her imagination against the iron hand of the Islamic Republic. Her father, who shared his love of books with young Azar, was imprisoned for speaking out against the prime minister and the minister of the interior.

“Read Dangerously” is structured as a series of letters to her late father, much like how James Baldwin and Ta-Nehisi Coates, who share a chapter here, wrote books in the form of letters to loved ones. Nafisi’s dispatches are eloquent essays on literature’s power to comfort the afflicted and afflict the comfortable. In addressing them to one she loves dearly, she provides a built-in layer of warmth and understanding. But she still hits hard.

Nafisi gets to the heart of the matter in the very first chapter, which looks at Salman Rushdie, a British American novelist of Indian descent. His 1988 novel “The Satanic Verses,” inspired in part by the life of Muhammad, prompted the Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini to issue a fatwa ordering Muslims to kill Rushdie. Talk about writing dangerously. “Three decades may have passed,” Nafisi writes, “but the issue at the core of the fatwa – the hostility of tyrants to imagination and ideas – is as relevant as ever. And it is relevant not only in dictatorial societies like Iran but in democracies like America as well.”

Nafisi wrote these words well before one Tennessee school board banned the Holocaust graphic novel “Maus” and a pastor in the state organized a good old-fashioned book burning. In the same chapter, however, she dives into Ray Bradbury’s 1953 novel “Fahrenheit 451,” in which books exist to be burned. You could say Nafisi is prescient, but the themes she’s tackling are timeless, older even than Plato’s “The Republic,” which she also addresses.

“Moments of extreme violence demand moments of extreme compassion,” Nafisi writes in her discussion of David Grossman, Elliot Ackerman, Elias Khoury and war literature. Books have a rare power to generate empathy, to connect people on a level of humanity, rather than ideology. To many, especially those who live for power, this makes books dangerous. For others, it’s what makes them magic.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: 'Read Dangerously': Azar Nafisi's must-read love letter to books