‘Eno’ Review: A Compelling Portrait of Music Visionary Brian Eno Is Different Each Time You Watch It

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Even next to David Bowie, with his alien regalia and mutating persona, it was Brian Eno who always seemed like the supreme spaceman of the pop-music universe. In 1972, when he first came onto the scene as the 24-year-old synthesizer wizard of Roxy Music, he sported a look that was pure glam, except that he somehow appeared even more baroque than the gender-bending rock stars of the time (the New York Dolls, Bowie, Lou Reed). They were Dionysian pansexual strutters, whereas Eno was his own unique thing: a delicate sci-fi gamine, a geek in thrift-shop drag. He wore light blue eye shadow and pinkish lipstick and jackets with huge shoulder pads that sprouted shiny black feathers, but his hair was thinning on top and long and wispy on the sides, and his pout gave him the look of a passionflower extraterrestrial.

As Eno began to create his solo albums of “ambient music” (a form he more or less invented, though it’s now so pervasive it’s almost hard to hear how out of the box it was then), he held onto his image as pop’s surreal harlequin eccentric. And even in 1976, when he cut his hair, ditched the glam threads, and began to collaborate with Bowie on what would come to be known as the Berlin Trilogy (“Low,” “Heroes,” “Lodger”), establishing his singular flair as a record producer, Eno still had the aura of an exotic mad scientist.

More from Variety

Roadside Attractions Buys Titus Kaphar's Acclaimed Sundance Drama 'Exhibiting Forgiveness'

Sundance Film Festival Courting New Host City for 2027 and Beyond

Part of it was his name. At the time, he was always referred to simply as “Eno,” which sounded vaguely interplanetary. Yet part of it was the mystique with which he created those records — and the ones he would go on to make with Talking Heads, Devo, U2, and Coldplay. Most fabled producers had a signature sound, but Eno’s production was all about what he coaxed out of the artists and what he pared away. He favored music rooted in repetition that was minimal yet majestic, propulsive in a holistic way. He wanted to leave the listener ecstatically spaced-out.

“Eno,” the portrait of Brian Eno that opened the Sundance Film Festival today, is a documentary that mirrors the spirit of Eno’s music in its very form. The director, Gary Hustwit (“Helvetica”), created it with generative software that allows the film to play in a different version every time you see it. Sections of it will land in a different order, and some won’t appear at all (replaced by others); the movie is reshuffled each time with an element of the random. How random? Well, it’s not as if the generative AI determines the order of everything. I’ve seen “Eno” just once, so I can’t compare it to other iterations of the film, but what I saw felt like it played in a sensible and, to a degree, predetermined order. The individual sequences are carefully edited, and if Hustwit, in putting forth this experiment, had tried to suggest that complete random assemblage-by-AI is the future, he might be getting threats from the Motion Picture Editors Guild.

As a documentary, “Eno” is sleek, seamless, and compelling, though one of the reasons it feels that way is that Hustwit, drawing on 500 hours of film and video from Eno’s personal archives, has made a movie that’s all Brian Eno. On the issue of talking heads, this film has virtually none, save for Eno himself, who talks all the way through it. The documentary uses his observations to fuse his past and present, his evolving images and shifting roles, in a way that accentuates their musical and spiritual continuity.

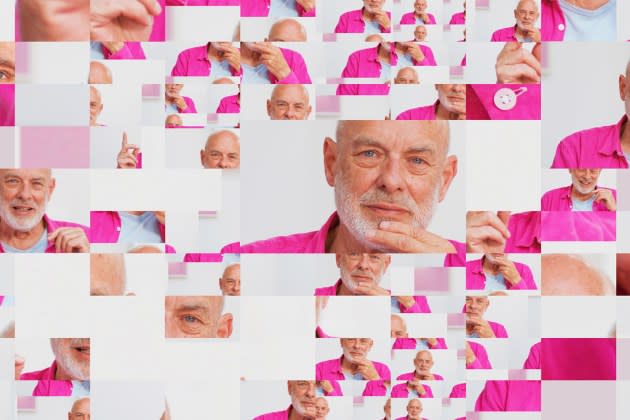

At least half the film consists of Eno today, with a shaved head, white beard, and designer glasses (the film was shot when he was 74), seated in his pristine all-white home studio in a handsome stone house in the British countryside, talking about his highly reflective, almost artisanal philosophy of creation. There has long been an aura of enigma surrounding Brian Eno, and one of the film’s delights is that he turns out to be a brainy but also quite funny and grounded middle-class British chap who has great stories to tell and is always willing to have a chuckle at his own expense. He narrates his journey of art for us, and though we learn next to nothing about his personal life (he makes a reference to his daughter — in fact, he has three children), or about any of his friends or relationships, the aura that’s constructed, of Eno as a kind of ebullient art monk, feels like it’s telling his true story in a different way.

Much of the footage is great. Here’s Roxy Music performing “Virginia Plain” on “Top of the Pops,” and my God how bracing they sound — and it’s all about the sound, with Andy Mackay squawking on the oboe and Eno using his synthesizer to draw aural curlicues in the air. Here’s Eno in the studio with Bowie, sculpting what seemed then like the sound of the future, and here’s an extraordinary clip of him in the studio with U2, as “Pride (In the Name of Love)” comes into being before our ears, with Bono scat-singing the lines. And here’s Eno talking about the songs that inspired him to want to do what he does — like Little Richard’s “Tutti Frutti,” or the feminine splendor of Ketty Lester’s 1962 version of “Love Letters,” or “Get a Job” by the Silhouettes (a song he says made him never want to get a job, which he says he never did).

Eno explains that he left Roxy Music mostly because he hated touring (“I wanted to get back to what I liked doing best, which is dabbling”), and he pays tribute to some of the artists who influenced him, like the Jamaican reggae producer Lee Perry, and talks about how he wanted to create “paintings that existed in time,” which is how he sees music. During the period of his ’70s solo albums, as good as a couple of them were (best all-time solo Eno track: “Needle in the Camel’s Eye,” the song that opens “Velvet Goldmine”), he says that he was regarded in England as “a failed glam-rock star.” He found his calling as a producer, which he has been for close to 50 years, though he never stopped making solo albums (he has close to 30 of them, including his gloriously ethereal music for the 1989 Apollo space-flight documentary “For All Mankind”).

As for his ruminating on music, that’s a constantly evolving pastime, and a little of it, I have to say, goes a long way. “Eno” presents itself as an experimental documentary about a musical warlock who never lost his trend-setting edge, and that’s all well and good. The version of the movie you see might not have some of the scenes I’ve described, which is fine. One of the reasons the film got made in the first place is that Eno says he wouldn’t have been interested in collaborating on a more conventional documentary about him. Yet I, for one, would have been happy to see that film, with testimonials from Bryan Ferry or whoever, and the appeal of “Eno” — like the appeal of Brian Eno himself — is that the film conjures a wholehearted and accessible experience within an experimental veneer.

Best of Variety

Sign up for Variety’s Newsletter. For the latest news, follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.