Ending cancer as we know it? National Cancer Institute Director Ned Sharpless lays out his vision

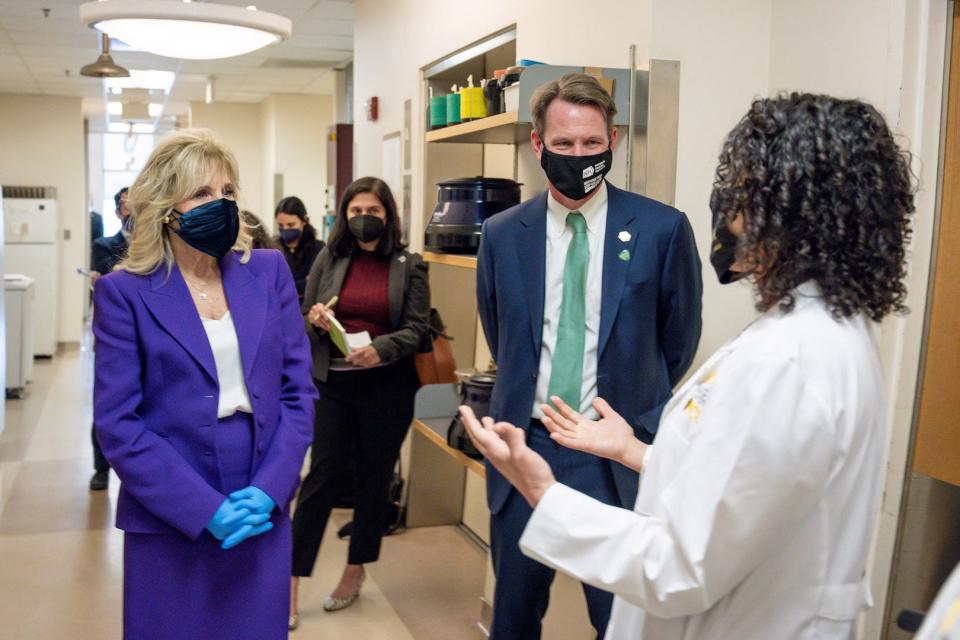

President Joe Biden, whose son Beau died of a brain tumor, promised to "end cancer as we know it." To better understand how that could happen, USA TODAY spoke with Ned Sharpless, director of the National Cancer Institute, which will help lead the effort.

Sharpless talked about the current "golden age" of cancer research, in which investments from decades ago are finally paying off for patients, as well as the role the NCI can play in making even more progress, despite the challenges that remain.

Question: What does the president mean by "ending cancer as we know it"? Is that really possible?

Answer: Notice what the president didn't say. The president didn't say eradicate all cancer. It's not likely to occur because of the fundamental links in biology between cancer and aging. It would be hard with the present technology and understanding of biology to end cancer deaths entirely.

What I believe the president meant by that is changing cancer from what it is, what we know today, to more of a disease where the age-adjusted mortality is much lower and where cancer death is largely occurring in the old and frail. So the idea is reduction of mortality and incidence in otherwise healthy individuals.

Q: What about extremely lethal cancers such as pancreatic cancer, or the glioblastoma that killed Beau Biden? Is it going to be feasible anytime soon to make progress against these?

A: That’s going to require new thinking and new ideas. The hard thing to predict is when that’s going to happen. In 2000, I would not have said we’re about to make huge progress in melanoma. It did not look particularly opportune back then, but lo and behold the world changed very quickly.

Q: A cancer researcher told me that although he had spent his life fighting the disease, the best approach would be to prevent it in the first place. What kind of progress do you expect in terms of cancer prevention?

A: The bad news about prevention is once you get past tobacco, obesity and the viruses we can vaccinate for, it starts getting harder fast. The NCI has tried many trials to feed people a vitamin or retinoid or some medicine that we think would prevent cancer. All of those have not really worked. There is no food we recommend you eat or vitamin we recommend you take to not get cancer. We recommend you stay thin, we recommend you exercise, but much beyond that, our recommendation is pretty limited for cancer prevention.

Early identification

Q: What about cancer screening? Is there potential to detect cancer early enough to become more treatable?

A: There are two real opportunities in cancer screening.

The things we do that we know work could be much more broadly used. We particularly have problems getting cancer screening to underrepresented minority populations, people who live far from cancer centers. We know now that low-dose CT screening for lung cancer is effective and it’s vastly underutilized.

We also believe there’s a new area in screening that’s very exciting: a series of different blood-based technologies that could find 10-50 cancers in the same patient at the same time. People who are otherwise healthy – perhaps over age 50 – would come in and get this test at some interval and based on these results be told you appear to be cancer-free this year or be told you need further workup. Such technologies are now ready for large-scale clinical testing. The National Cancer Institute can be very helpful, because these are big trials that require lots of patients.

Q: Isn't there a risk of over-diagnosis with such an approach?

A: The critical question is do these tests find the more aggressive cancers that are likely to be harmful and not the indolent, clinically insignificant cancers – and that’s an open scientific question.

Golden age

Q: You were appointed by President Donald Trump and are now serving under President Biden. Has the change in administration affected your work at the National Cancer Institute?

A: It’s an exciting time to be involved in the NCI no matter’s who’s president. The whole pandemic has been very disruptive both to cancer care and cancer research. I can’t say it’s been fun, because it’s a national tragedy, but being able to work in the benefit of public good during this period has been very satisfying professionally.

To have a president of the United States who has a personal connection to cancer, to have someone who has such a good understanding of cancer research and such a clear goal of ending the tragic elements of cancer as quickly as possible is really exhilarating for our field.

It’s a very good time to be a cancer researcher in the United States.

Q: You've said we're in a "golden age" of cancer research. What do you mean by that?

A: It was 2001 when the golden age started for me. A bunch of investigators were able to show that cancers we thought were kind of the same – we thought we had one kind of breast cancer, one kind of lung cancer – that they weren’t, that there were many different subtypes.

In the old days, I would give everybody with colon cancer the same drug, and it would work in about 20% of patients, and you’d be like wow, that’s weird, why doesn’t it work in the other 80%?

Now we say: I want a drug that works in the 5% of lung cancer patients with BRAF mutations or with EGFR mutations or whatever. When you divide cancer up into those discrete fractions it’s a much more tractable problem.

Q: But that didn't begin to pay off for patients right away, right?

A: It was in 2010 when the therapeutic gravy train got going in terms of massive new numbers of drugs and advances you see every year now in cancer research.

Putting the immune system to work

Q: Among those advances, presumably, was immune therapy – using the person's own immune system to fight their tumors. How is that changing cancer care?

A: A hundred years from now, we’ll teach medical students that there are four ways to treat cancer: surgery, radiation, chemotherapy and immunotherapy. Maybe there’ll be a fifth or sixth thing, but there’ll be at least those four and immunotherapy will be critically important. It will be really the only way to treat certain kinds of cancer.

Q: Has cancer immune therapy delivered on its promise, or are more treatments still to come?

A: As profound as it’s been to date, the field is really in its infancy. (The challenge) is to try and really understand how to make the immune system work for all patients, not just the 10-20% that benefit very profoundly on average. There are some tumors that look like they ought to respond and they don’t. There's something holding the immune system back. How to get rid of that barrier is sort of the low-hanging fruit.

Q: What's going to be the next great idea after immune therapy?

A: One of the problems we have in cancer research is that there are so many good ideas. People are leaving other scientific fields to become cancer researchers. If we don’t continue to put more money aside for that investigator-initiated science, the success rate of those applicants will drop precipitously, and then we won’t get to that paradigm-changing idea that we need to fund.

What can the NCI contribute?

Q: Collecting patient data has become hugely important in cancer, to better understand the differences among cancers and how to treat them. What is the NCI doing to improve data collection?

A: One of our main roles is to build the infrastructure: cloud computing, data use dictionaries. We're also doing a demonstration project in childhood data collection. The idea is to learn from every child with cancer in the United States, to really figure out what’s going, so we can learn as quickly as possible how to treat those patients. It’s harder than you might imagine – balancing issues of research and patient privacy are very challenging – but I think we can do it.

Q: What are some other roles for the NCI? What are the areas where it can have the biggest impact?

A: (Let's say) we have a therapy that works and we want to see if we can give less of it. That’s not really in the interest of a pharmaceutical company, but those trials can be very, very important for patients. We just had a major de-escalation trial in ER+ breast cancer where we showed we can give less chemotherapy to women and have equivalent outcomes. That’s a tremendous benefit to those patients, though it’s the kind of thing the NCI has to do.

Q: President Biden has made equity a cornerstone of his administration. In what ways does this play out in cancer care?

A: We have known for decades that outcomes in cancer are largely related to access and to race and socioeconomics and wealth and education. The NCI spends on the order of $500 million a year to study the barriers that create health disparities in the United States and what to do about them.

If you want to get back to the president’s goal of rapid progress against cancer, you have to take on the equity issue. The president was very clear. He didn’t say, "We want to end cancer as we know it for some people." He wants to end cancer as we know it for everybody, and so we really have to make sure that these advances – some of these almost miraculous new therapies that we have – are available to all patients regardless of wealth, access, race (or) access to education.

Q: What do you foresee in the next year or two as NCI has more money to spend and more public attention?

A: As we emerge from the pandemic, there is this combined sense across our field that all these different approaches and new technologies and new vigor and emphasis from Congress and from the White House, is going to be a very good period of cancer research. It’s really up to us to use this national investment to make a difference for our patients.

This interview was edited for length and clarity.

Contact Karen Weintraub at kweintraub@usatoday.com.

Health and patient safety coverage at USA TODAY is made possible in part by a grant from the Masimo Foundation for Ethics, Innovation and Competition in Healthcare. The Masimo Foundation does not provide editorial input.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: National Cancer Institute Ned Sharpless helps lead Biden cancer effort