‘Empire Of Light’ Helmer Sam Mendes On How Olivia Colman’s Performance Was Informed By His Own Mother’s Mental Breakdowns, Why Obsession With Nicole Kidman’s ‘Blue Room’ Nudity Stopped Him Reading Reviews & How His Killing Judi Dench’s M Led To 007’s Death

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

After racing to finish his upcoming Empire of Light and seeing Searchlight launch at festivals leaning into the Cinema Paradiso-style movie love letter element, Sam Mendes is ready to come clean about what his first solo-scripted film is really about, and the experiences that informed it. The grandeur of the seaside 1980 London movie palace is certainly the backdrop for an unlikely romance between a middle-aged theater manager (Olivia Colman) and a dashing young ticket taker (Micheal Ward, whom you’ll recognize from the opening episodes of Steve McQueen’s Small Axe mini). The youth is dealing with the rampant racism that put young men like him in danger in the UK.

But here, the Oscar- and two-time Tony-winning director Mendes bares what the film is really about: the mental illness and slowly building breakdown of Colman’s character, which was informed by the filmmaker’s own experiences with his mother. His goal: to shine a light on a condition that too long has been suffered in silence.

More from Deadline

DEADLINE: When we did the first interview right off the plane when you finished 1917, you said the inspiration came from asking your father why your grandfather washed his hands so incessantly. He told you the man could never shake the memory of the mud from being a runner in those WWI trenches. Empire of Light launched at festivals characterized as being in the spirit of Cinema Paradiso, this love letter to cinema. That is what you talked about and it’s certainly there. But the center of the film is Olivia Colman’s emotional meltdown when her character stops taking lithium. You dealt with depression in Revolutionary Road, but this was painful to watch and felt real, like the writer had knowledge of the condition that went beyond research. Now, you’re prepared to discuss how for the second straight film, you are telling a story based on you and your family.

SAM MENDES: It’s funny you should mention 1917 because, on the surface, you would think there was no continuity at all between a movie about the First World War that’s one continuous shot, and a movie that made in a much more contemplative style, and set in the 1980s in England. But the truth is that there is a continuity and that one did lead to the other.

DEADLINE: In what way?

MENDES: The feeling I was getting closer to my own family, to my own…the things that made me as a child, as a grown-up, the things that have obsessed me all through my adult life, and the central experience of my life. I was growing up as an only child with a mother who was falling apart mentally, who had a mental illness. Watching that cycle will feel familiar to people if they’ve been around that particular form of illness.

Call it what you will — schizophrenia, bipolar, manic depression. You can feel it on someone when you meet them. You develop a sort of sixth sense when you’ve grown up with it. And you’re watching every second of the day to see whether she’s going to collapse or whether she’s going to rebuild. And a tiny thing in that circumstance could mean my life changed. That [mood] change in a second, or a little bit more makeup or the way she did her hair.

RELATED: Sam Mendes’ Romantic Drama ‘Empire Of Light’ For Searchlight Gets New Trailer

Going into 1917, I was very clear about the family content of the film. It has taken me quite a while to get to this place, with you. I’ve been on a journey since Telluride, since the movie opened, to be able to acknowledge it, and talk about it myself, what is really at the center of the film. There was a feeling in the beginning of the movie, it was packaged that way, that it was a celebration of movies.

DEADLINE: It isn’t?

MENDES: That is in there, sure. But it’s only there as a counterpoint to the center of the film, which is it’s about mental illness, fundamentally, at its roots. Olivia Colman’s performance is I think an extraordinary rendition of watching someone disintegrate because of schizophrenia or bipolar. I hadn’t, in Telluride, found a real way of talking about me personally. But I think when you are a parent of young kids, as I am still, you are always reflecting on your own parenting, the vulnerability of children and how you were brought up when you were their age. How heroic the act of parenting is, even if you’re healthy. But when you’re unhealthy and suffering and struggling and laboring under this incredibly dark force, which is mental illness, how it’s even more heroic and extraordinary that you can bring up a child.

So, it has definitely been a journey of discovery for me, and it is linked, in a way, to 1917. And you look back … you mentioned Revolutionary Road, and reflect on those figures in … I reflect on the figures in my other works that have also been part of that story. April’s journey in Revolutionary Road. Annette Bening and Allison Janney in American Beauty. One of them is my mother, pre-medication, hyper, very driven, entertaining, but also hysterical — and I mean that in a literal sense — and the other, Allison Janney’s character, medicated to the point of almost paralysis. And it even figured into Judi Dench’s M in Skyfall.

DEADLINE: You mother’s depression was an influence even in your James Bond films?

MENDES: She’s this complicated mother figure who is both the reason that he’s there and also literally, almost his worst enemy in a couple of moments in the movie. And the person who orders his death, ironically.

I think all those things are there, and this is a kind of natural conclusion to that, in a way. And it has been a fascinating journey. I feel I have learned a lot, even in the last couple of weeks, of just being able to talk about it openly, like I’m talking about it with you. But you develop this sixth sense about other people who might be suffering the same illness.

DEADLINE: There is a stigma to it also. I recall once telling a co-worker I’d started taking Zoloft, just to take the edge off and not hang onto slights so long. I stopped because at the time, I felt I needed the edge made me better at my job. I don’t feel that way now and I take a small daily dose. This person, who had these issues and whom I told in hopes they might give it a try, instead spread word I was some kind of drug addict. I was very disappointed.

MENDES: Mental illness is so difficult to talk about. And that the person who suffers the mental illness…when they’re “better” or when they’re not in the throes of a full-on manic episode, they then refuse to acknowledge the existence of the illness. So, you get this cycle happening that they have to re-create. They’re drawn to the exhilarating highs, this wonderful feeling of power that comes with coming off the meds and just feeling like you can say f*ck you to everyone.

That is a very exhilarating feeling, and then the crash follows, and it becomes this cycle. But very difficult to talk about, very difficult to explain, and one of the reasons that, as a storyteller, what you’re trying to do is you’re trying to show “knocked down.” You’re trying to show someone in the process of mental illness. It’s inexplicable, but the journey has a kind of weird logic to it, and that’s what I was reaching for with Olivia.

DEADLINE: How did you get there with her?

MENDES: I was very fortunate in that I had an actor who was capable of hitting every single notch on the escalating scale of hysteria that goes with coming off medication that is making you feel dulled. Your senses are dulled. You have low self-esteem. You put on weight. Often, you feel not yourself. She describes it in the movie, as “I feel, numb.” And then something happens, often a love affair, some strange battle at work or some fight for power.

It triggers a kind of rage and a fury, and it leads to lack of sleep. And this lack of sleep continues, and then you start literally…you know, this is a very crude way of putting it, but the body just starts secreting, the brain starts secreting an enzyme, and you begin to trip. I mean, you begin to believe a different reality.

DEADLINE: What a frightening reality for one who suffers this…

MENDES: What’s been interesting is the way that people view this movie. It is completely different if you have experience with bipolar, than if you don’t.

DEADLINE: How?

MENDES: People who don’t, think, well, she’s on a couple of antidepressants. What’s the big deal? And I think that mirrors exactly what happens in society, between the people who really take it seriously as an epidemic, which is what it is, and those who don’t. Those who don’t go, well, what’s the problem? Why is she suddenly different? Why is she changing so…that’s a big leap. Well, you know, when you’ve lived it, it’s not a big leap. You watch people literally fall apart in front of your eyes. But in a way there’s a sort of magnificence to it. There’s a sort of scale to it. It’s like a group drama. You know, it’s a fireworks display.

DEADLINE: Why do you say that?

MENDES: Because, often, they’ll become far more creative, far more articulate, far more charismatic, far more magnetic as a person. And you’re thinking, well, this is amazing. What they’re saying is amazing. But there’s something wrong, and I can’t put my finger on what it is. That’s why it’s so difficult to deal with. Some people have an idea of depression, for example, of someone just being quiet and sitting in a corner, dressed in black. I’ve lost count of the number of people who describe somebody who’s taken their life and said, “He looked fine to me. He was laughing the previous day,” and you’re like, you don’t get it. It’s absolutely invisible on the surface, and sometimes they appear more healthy, more articulate than you’ve ever seen them before.

This is why I was drawn to this way of expressing it, through drama. Ultimately, you’re showing somebody on that journey, and if you tune into that dog whistle — mental illness at the beginning — you go on the journey with her. And you feel the intensity of that performance, which is extraordinary. And if you don’t, you worked on a different film. And I think that’s pretty interesting.

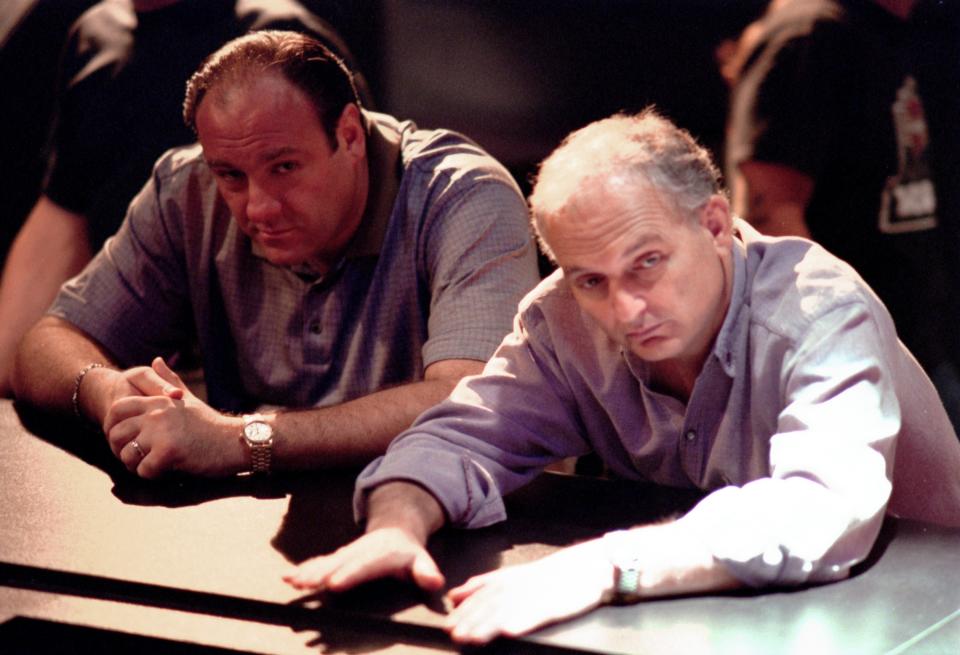

DEADLINE: I just re-watched the episode of The Sopranos where Annabella Sciorra turned in this intense performance as the mistress Tony Soprano meets in his psychiatrist’s office, and who melts down into obsessive behavior that endangers her life because she threatens to expose the affair to Tony’s wife. David Chase based some of the issues of depression on his experiences with his mother. Tony realizes he was attracted to the schizophrenia he grew up with exhibited by his own mother. It is striking how this manifests itself into the creative process of the children who grow up with this…

MENDES: This is one of the great pictures of a mother who is impossible but continues to fascinate. Livia Soprano. The first season of The Sopranos…the whole thing is a masterpiece, unquestionably, but I remember so clearly the brilliance of that first season. The only thing that separates Tony from all the others is that he talks. He talks to the therapist played by Lorraine Bracco. And then you have this extraordinary portrait of an old woman, who is just furious, unreachably furious, lionizing and idealizing her ex-husband, who you know, even though you never met him, is a complete motherf*cker.

I mean, it’s a bit awful, but he’s trying to tell her, dad wasn’t an angel, but she keeps saying he was an angel. I remember watching, and thinking that’s what it’s like! There’s no way in. It’s just like, no, the f*cking walls come down. And I think what was so amazing is that there was a sense, with The Sopranos, that David Chase himself was going through what Tony Soprano was going through, which is that he was just starting to talk about what made him. And why he keeps being drawn back to the same things, even though he knows.

[Dr. Melfi] can’t even talk to him about the violence, because professionally, she has a code of conduct. But she’s clearly thinking, why are you [engaging in this affair with my unstable patient]? And he keeps being drawn back into it, again. It’s genius, really. That’s what is most difficult thing to dramatize in the film, and I hope we achieve it. Here is a woman who is fighting with every fiber of her being to not get taken into a mental hospital, a mental hospital where people are sick … I mean, I saw sh*t in mental hospitals that were not … I don’t want to go into the details, but they’re scary places. There are huge tattooed guys. Drug addicts. There’s people … it’s violent. It’s strange. It’s disturbing. People screaming at night. It’s scary, right, when you’re putting your own mother into one of these places. So you have that, on the one side.

You have her fighting with every fiber of her being not to go into that … not to get taken to that mental hospital. And yet, she’s got her bags packed, and she’s ready to go. She knows she needs help, but she will refuse to acknowledge she needs help. That, to me, is denial. You know you have to leave, but you don’t want to leave, and you will fight, almost to the death, to not go. Now, how do you describe that to somebody? It’s very difficult, but you dramatize it, that when you show it, that there is a sort of strange logic.

DEADLINE: What is the logic?

MENDES: She is wanting, with ever fiber of her being, to hold onto her dignity. She’s got her bag packed, and she will go there. But she will never admit that they’re right, and those two things have to go hand in hand. I remember the moment with American Beauty. I was reading the script and I thought, wow, this is not just funny and cool and sharp as a tack. It’s also profound. It’s when Ricky [Fitts, played by Wes Bentley] turns to Lester Burnham [Kevin Spacey] and says, never underestimate the power of denial.

DEADLINE: Why did that land with you?

MENDES: I thought, there’s a film in here that speaks to me. Me, Sam. I understand that, the thing that drives the plot in American Beauty, is a colonel who lives with his son, who is, in fact, not as heterosexual as he claims to be. And what will eventually lead to Lester’s murder is the fact that that man is not who he says he is. So, however much the surface of these movies varies and has shifting perspectives, counterpoints, visual interests, all of those things, the motive of the stories is that denial. I think that that’s the case in this movie, too. So, I see now, in the last few weeks, weirdly…because I drove it very, very fast to get it ready for the festivals. Because these days, post-pandemic, no one wants to drop a small, middle-scale movie in the marketplace in December.

DEADLINE: Better for an awards-caliber film to make its mark early in the season, and 1917 might have had a better outcome had it been ready earlier.

MENDES: The heady days of 1970, I’m afraid, are over. Of course if your film fit more of a genre appeal …but this is not a genre movie. So, you have to work harder to find an audience for a movie like this. In order to do that, I wanted to get it ready for the early festivals. While I’d worked out what the movie was, I hadn’t worked out my relationship to the movie. Also, the audiences begin to tell you things.

DEADLINE: Like what?

MENDES: What they told me was that they were interested in the mental illness. They were interested in Olivia’s journey. They were less interested in the movie part of it. In a way, it really has been a great journey of discovery. Coming out around the same time of this interview is a new trailer that reflects that [the trailer released yesterday.] Describing to people and hoping that they will come and see a world with these two broken people, outcasts for different reasons. If you’re an outcast, it’s possible that movies and art and literature can put you back together again. That’s something I do believe, ultimately, even though it makes me a romantic in this case.

DEADLINE: You were an only child, so it would be natural that you spent more time than anyone with your mother. When did you realize something was amiss with her?

MENDES: In my own memory … I know a very, very big breakdown happened when I was about 3. Which I don’t remember, and I went to live with my dad for some time. When I was about 9, I didn’t see it coming at all, but that was a huge breakdown. And then, once your parent or the person you depend on most in the world has proved themselves to be not as dependable as you thought they were, you fear it all the time.

Your radar is tuned into every possible sign that your parent is going to do the same thing again. Is going to leave you, is going to abandon you, is going to suddenly become a different person. It could be any number of small things. Generally speaking, a shift in the tone of their voice, an adjustment to the way they want to appear, how they want to seem to the world, not necessarily to you. Their dress might change.

The way they dress. Their scent, their perfume, their makeup, their hair, all of those things, gradually. But in the way that when you have children, your child grows incrementally every day, you don’t notice the changes, and then one day they’re standing shoulder to shoulder with you, this is a little bit like that. It’s undetectable. It’s many different things, all adding up. It often involves immense highs.

I try to dramatize the moment that Stephen spots it and we, as an audience, first spot it in this movie, on the beach. It will be some perceived slight, some small thing that you think is pretty much irrelevant … that they take irrationally huge umbrage at. Like a sort of earthquake, based on some small throwaway comment. And it becomes this huge issue. It’s all of those things combined, really, but it’s more than that. It’s a force field. It’s the temperature in the room, changing. It’s molecular. It’s a shift in … someone walks in, and you don’t know what’s wrong, but you know something’s wrong. I think that’s the only way you can describe it.

When you’ve experienced it, you tend to spot it or fear it in others, as well. But at the same time, I find myself drawn to those people, interested, fascinated in those people. In a working environment, the very things that I had to do as a child, I do now professionally. Which is, watch people all the time for signs that their narrative is about to change, when they’re leaning in. And here, we had this very unusual experience for me; I was doing professionally what I did throughout my childhood. I was watching somebody, in this case, playing my mother, a proximate version of my mother, for the things that I was watching her for, when I was a child.

DEADLINE: What were the signs you looked for?

MENDES: Talking to her. How much eye makeup? How long since she’d washed her hair? How greasy was her skin? How smelly was she? Had she…changed her clothes? All of these things. How many nights had she not slept? All of those things, and not only the bad things, but the good things, too. The exhilaration of coming off the meds, the freedom, the sudden sense that you are your own author. You can achieve anything. There’s a very, very good documentary made about bipolar by Stephen Fry, who is bipolar. He asks all of the bipolar sufferers that he meets, would you sacrifice the highs if you knew you could just get rid of the illness?

DEADLINE: What do they say?

MENDES: They all say no. They all say they are addicted to the highs, and they’ll suffer the lows, the crash, the humiliation of realizing you were ill and the things you did when you were ill, just to have that feeling of power again. In a world where, especially in this period, as a middle-aged woman, you are constantly oppressed and told you’re a second-class citizen.

DEADLINE: Colin Firth plays the theater manager, a married man who summons her to his office for sex when he feels like it…

MENDES: I went out of my way to show how she had been oppressed by Colin Firth’s character and how she had been aware, very aware, of his cruelty without ever saying anything about it. Which is a common thing. They bottle it up, bottle it up, bottle it up, and eventually, it comes out in an avalanche against the person who had no awareness, maybe because she’s not saying anything. Colin’s character clearly thinks he’s a bit of a catch, and that she wants the relationship. He has no idea. And Colin, rather brilliantly, said his character is not exactly fluent in the language of consent, which is a very English Colin Firth way of saying it. Your self-esteem is so low, you feel they desire you. This is wonderful. This is a good thing. It begins to build you up, but of course, at the same time, you allow someone to aggressively take more and more advantage of you, it’s really profoundly unhealthy.

DEADLINE: The scene where she’s sitting on the bench, and Steven [Micheal Ward] and his girlfriend pass by her and say hello. You see the sadness in Olivia’s face, like it must feel to a former alcoholic looking enviously at people who can drink recreationally, or in her case engage in a relationship without the extreme highs and lows that make life worthwhile, but will trigger her downward spiral. I’ve never seen it portrayed on the screen that way, where she realizes her fate, which is to be as she calls it…numb.

MENDES: Yes. I never had to … it was often the social services and the doctors that took my mother into hospital. I had to pick her up on several occasions. The vulnerability … all that was stripped away. It’s almost like the baby bird. Something so vulnerable learning to walk almost again. No makeup, no self-esteem. And a very clear memory of what’s happened. I don’t think they wake up after being sedated for a week with no memory. I think they remember everything. One way of dealing with that is to admit it and talk about it, which is perhaps humiliating and very difficult. The other is to deny it, which was the case with the situation I found myself in. Or simply to change the subject.

But I think that one of the things I find very moving about Olivia Colman’s performance in that scene is her capturing of that sense that it’s almost as if, for Stephen looking at her, she barely knows him. And it’s wounding I think, but when you’ve had a powerful relationship, you are looking at the person who’s been into a mental hospital and come out heavily … just with the sedation wearing off and a memory of the humiliating things they’d done. It’s almost as if they don’t have the energy anymore to go back. It’s like having to meet them again for the first time, and that’s disturbing when it’s a friend. But it’s even more disturbing when it’s your own parent.

DEADLINE: The dynamic between those two characters is they are former lovers, and he is much younger than she. It sounds like it mirrors how a son would look at his mother when she’s had a meltdown, and then the shock and damage done to the young person and the regret and humiliation felt by the parent for being a wrecking ball. How much of this was on your mind as you were writing this script?

MENDES: I think it’s two parallel stories that run alongside each other. They’re both rites-of-passage stories. Hers is a rite to passage down into the darkness and back out again in a way that perhaps, you might hope, be the last time she has to go through that, with a sudden increase of understanding at the end. Some sense of hope, and it felt very important for us as an audience, but also for me, to believe that understanding, compassion, kindness, and art can show you a way through. And that’s what film does for her. I think the story does that for him, too. There is another rite of passage, and that is a young Black man, refusing to be defined by his own trauma. Optimistic, positive in the face of many, many reasons why you shouldn’t be in a world unlike the world she lives in, which is basically in which the cards are stacked heavily against him. She gives something to him, and he gives something to her.

DEADLINE: He is over his head trying to process her problems, but also has to deal with the profound level of racism in the UK at that moment …

MENDES: I wanted her to be infected by his positivity, his spirit, his joy, his youth, his knowledge and the way he sees the world. And for him to be affected by her wisdom and belief in him and love of things that he knows nothing about, poetry being one. That was the journey of these two characters through the movie …

DEADLINE: And then you add this movie palace, at what must have been your coming-of-age moviegoer period, with films from Raging Bull to Chariots of Fire and others.

MENDES: The moment that the cinema, as it were, arrived as an ideal for me, it pulled both of them together. It gave them somewhere where they could meet, where they could be together, and the abandoned part of the cinema gave them a world they only occupied together, but no one else goes into. Which is this Through the Looking Glass part of the film where, in another world, in a different universe, it would be possible for a 20-year-old Black man and a middle-aged white woman to be together. But the moment they step outside, it’s different. So, to me, two things in my childhood were rendered really in this Hilary story and my teenage years. By Stephen’s story, a time of racial upheaval, great racial tension in the UK and around the world, but particularly in the UK. It was the formation of my own politics really, because it was also a time of great positive role models for young Black and white men.

And my many, many hours in cinemas, and projection booths and dark auditoria, whether they be theatre or movie houses. The smell and feel and look of the place, the fading grandeur of it all. I didn’t map it out like a scientific experiment. You go where your heart tells you to go, though, and you hope that the audience goes on a journey to be with you. If they do, great, and if they don’t, also great and particularly when you’re not given the kind of objectivity that you’re normally able to achieve directing someone else’s script. This time, as the sole writer, I just had to go home and talk to myself in the mirror. There was no one there in that regard. It was a much more solitary an experience than I’m used to.

DEADLINE: You’ve been really honest here. Will it make it harder for you to read the reviews? In this context, you are bleeding on the page in a way similar to Alejandro Iñárritu’s Bardo, a nakedly personal film that he got a bit bashed for after its premiere.

MENDES: As a director, I think you’re so used to feeling completely front and center when it comes to both criticism and praise. You feel, what a privilege to be able to use some of your life as part of a story that’s made for people to watch. But I honestly don’t read reviews anymore. When I was running the Donmar in the ’90s, I didn’t just read every review. I used to wait outside King’s Cross Station. In those days, there was no such thing as the internet. I just waited for the newspapers to be delivered at 2 in the morning, because they used to drop huge piles of newspapers, going on the trains up to the north. They would have these temporary newspaper stands at 2 a.m. outside King’s Cross, and I would just sit there in my car waiting for these newspapers to arrive, my heart pounding, for hours. And I’m not just talking about the ones I directed. Every f*cking production of the Donmar, which is partly because at that point, there was a sense that if we had a dud production or two in a row, we would have to close, because we had no funding. It felt like life and death for me, even then.

DEADLINE: What changed?

MENDES: 1998, when Blue Room opened on Broadway. There was an enormous fuss about The Blue Room, and most of it was along the lines of Nicole Kidman does the whole play naked. The reality was she was naked for all of three seconds, with her back to the audience, pulling up her panties and then putting a blouse on and then turning around. I found it really distressing, the degree to which it had become this cultural talking point, and not helped by the reviewer in the Daily Telegraph calling it “pure theatrical Viagra,” if you remember. You think, man you need to get out more. I’m reading Entertainment Weekly, because I was still reading everything, and there’s a map of the Cort Theatre on Broadway, 48th Street, where it showed you the seats from which you could see more than just Nicole’s butt. It showed you that there were like six seats in a box, where you might get a view of her side boob. I was like, that’s it. I’m stopping right here. I am not going to read anymore. I’m done. It was quite useful in the end so I want to say thank you to whoever the f*cking guy was who spent a week, drawing a map on the back of a f*cking envelope. No one cares anymore, but it made me so upset. I went to the opposite extreme, and it has been that way for my entire movie career, because the next year, I made American Beauty.

DEADLINE: So you have to find other ways to feel validated than the critics?

MENDES: I’m very proud of this movie. What I wanted here, though, is for the audience going into the movie to have the right and not the wrong context. I don’t want them thinking this is going to be about the magic of the movies, and then they have to watch someone mentally disintegrate physically in front of their eyes, waiting for the bit where she watches a movie. No. That’s why I’m talking to you. I feel very strongly that people are going to like it or not like it, but the one thing you can effect is how they go into it, and frame it properly so that they know what to expect. What I think you can expect here is two really magnificent performances, one of the great Olivia Colman performances on a level that even shocked and amazed me. I wrote it and imagined it, but I could not have imagined what she would do with it. I think she’s a genuinely great actress, and I’m beyond sort of pathetically grateful to have someone like that pick up what I’ve written and make it into something that is close to art.

DEADLINE: Prying question: did your mother find her way out of the darkness?

MENDES: Yeah. And I think it’s a very hopeful movie, and that it does show a way through. I think if it didn’t, it would be much harder to make. I don’t think it shows an easy way, and I don’t think it’s definitive. But life is a contact sport, you know? It’s a bruising world to live in, and the movie, ultimately, is about two very vulnerable people trying to make their way through, without getting damaged or killed. And what other stories are there to tell at this moment?

DEADLINE: Way off topic, but one I gotta ask you., I watched No Time to Die and how Daniel Craig ended his James Bond tenure. I wondered how Sam feels, after spending so much time breaking down Craig’s 007 and leaving it for another director to take him out.

MENDES: Mike, I would gladly have put a gun to his head. Not being the person to finish him off … I tried. But he just wanted one more little movie, and I see, okay this is it. He’s walking away. He’s got the girl. But we left the baddie alive, and that’s always fatal, isn’t it? You got to kill the baddie. I have to say that the theories from watching the movie was like one of those lucid dreams. Which is, like, all these people that I spent literally years of my life with, Léa Seydoux, Daniel, Ralph Fiennes, Ben Whishaw, Naomie Harris, all of them …

In this vaguely similar world, we’re all doing these vaguely similar things. My only thought when I was watching it – and I watched it in my local cinema, incognito, because I didn’t want people watching me watching it. I’d missed the premiere because I was in New York doing The Lehman Trilogy. I didn’t go to any of the red carpet events, and I thought I am the only person in the world seeing this movie in this particular way.

No one will see it quite like I am. There are so many associations, but yeah, I was a little jealous of the fact they got to sign off with a big bang at the end. I thought, wow. You know, there was definitely a few meetings where I was like, should we just kill him? And they were very resistant in those days, but hey, obviously, their requirements shifted slightly. But I certainly enjoyed it hugely, and it was wonderful to see all my friends doing these things.

DEADLINE: Sounds like after all the existential crises and danger you put him through, you’d have liked to see Craig’s 007 walking off into the sunset as opposed to the way it was done.

MENDES: To be honest, I was amazed that they did it. But in a way, you could say it was my fault because I killed M. That was the first moment in the series when an actual character acknowledged not only dying, but getting older in any way. Rather than just being replaced by another actor. So, Skyfall changed the paradigm slightly, they acknowledged Bond was aging. He talked a lot about aging in Skyfall, and M dying and the changing of the guard, and then a new M and a new Q and a new Moneypenny. So, in a way, I certainly feel like it was true to what we had been doing.

So it didn’t bother me. I definitely didn’t think, oh, they shouldn’t have done that, what a terrible idea. I suppose that was inevitable, because once you’ve given one great actor a death scene, there’s going to be another great actor on set thinking, maybe I need one of those.

Best of Deadline

Sign up for Deadline's Newsletter. For the latest news, follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.