Emmys: Celebrity Stories Dominate Documentary and Nonfiction Special Category

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

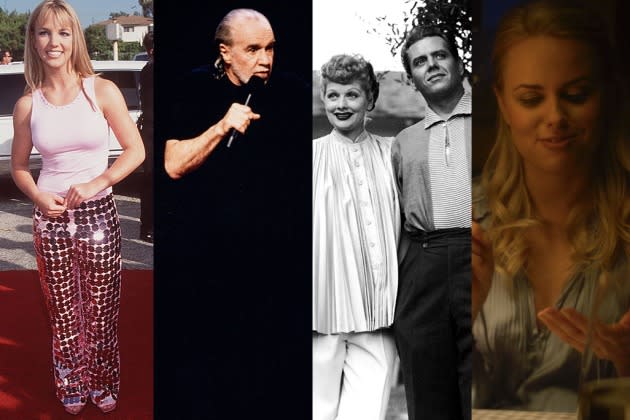

This year’s Emmy nominees for best documentary or nonfiction special include four examinations of celebrity in its various forms — from the tabloid target Britney Spears, the comic philosophies of George Carlin, the romantic and working partnership between Lucille Ball and Desi Arnaz to the altruistic efforts of chef José Andrés. Rounding out the category is The Tinder Swindler, a true crime doc about a man who used the dating app to scheme unsuspecting women out of cash. Here is a rundown of the contenders from The Hollywood Reporter’s writers and critics.

Controlling Britney Spears: The New York Times Presents (FX/Hulu)

More from The Hollywood Reporter

'Zoey's Extraordinary Christmas' Gives a Second Life to a Beloved Musical Comedy

This Year's Award for Wacky Emmy Category Goes to... TV Movie

In the follow-up to Framing Britney Spears, Controlling Britney Spears is directed by Samantha Stark with Liz Day as a supervising producer and reporter, and features interviews with insiders who had knowledge of Spears’ life while in the conservatorship. In their interviews, they speak openly about how Spears’ life was controlled and react to the singer’s emotional testimony. Those featured include Spears’ former longtime assistant Felicia Culotta, her former head of wardrobe Tish Yates, promotional tour manager of Spears’ Circus Tour Dan George, and Alex Vlasov, a former executive assistant, operations and security manager of Spears’ longtime security company Black Box Security.

One of the bigger accounts shared was from Vlasov, who assisted Black Box Security Inc. president Edan Yemini for nine years. “I was the only person at Black Box who knew everything,” he shared. “Edan was so relieved when he saw the first documentary [Framing Britney Spears]. He was so relieved that he wasn’t mentioned, Black Box wasn’t mentioned, Tristar wasn’t mentioned. It was his biggest fear that security would somehow draw any attention.” Yemini declined to answer questions about his firm’s work with Spears for the documentary. — Lexy Perez

George Carlin’s American Dream (HBO)

“We don’t really have philosophers anymore, but we have comedians,” Chris Rock says in the second episode of Judd Apatow and Michael Bonfiglio’s two-part documentary, George Carlin’s American Dream.

The accurate gist and genesis of Rock’s observation is the compelling evidence that George Carlin both transcended and changed the parameters of his chosen profession. It’s been nearly 14 years since Carlin died, but based on his continued social media ubiquity, his words have lived on and remained crazily specific, as if every unanticipatable catastrophe of human culture was somehow anticipated by only one man. On any given day, whether the trending topic relates to reproductive rights or environmental disaster or political hypocrisy or the power of free speech, one subset of fans is lamenting that we’ll never know what George Carlin would have said about the news du jour, while another set is posting the blistering stand-up set that illustrates exactly what George Carlin did say about that topic.

That Carlin left behind countless hours of clearly articulated, increasingly irritated expressions of his worldview doesn’t change the most persuasive aspect of Apatow and Bonfiglio’s documentary — namely that Carlin was a protean embodiment of the country that spawned him. Not only did Carlin’s life have a second act, but he had a third and fourth act, and the comic he was in the mid-’90s and ’00s almost surely wasn’t the comic he would have been today. Which makes the documentary simultaneously a celebration and a tragedy. — Daniel Fienberg

Lucy and Desi (Prime Video)

Among the rich selection of stills and footage in the unexpectedly affecting Lucy and Desi, there’s an image that might strike you with its likeness to the film’s director, Amy Poehler. The photo captures Lucille Ball, in one of her daffier getups, beaming at the camera: a wide-eyed, beautiful clown. More than 70 years after I Love Lucy transformed the airwaves, many people working in television can trace their inspiration to that trailblazing sitcom and its beloved stars. But Poehler brings a particularly powerful sense of connection and understanding to her debut documentary. Like Ball, she’s a funny woman with serious clout in the TV business. And she knows a thing or two about being part of a famous comedy couple whose marriage ended in divorce.

With an insider’s perspective and access to Ball and Arnaz’s archives, Poehler zeros in on a showbiz love story. Beyond the pair’s romantic bond, there’s a postwar nation’s infatuation with them. Like a recent documentary about Dean Martin, a fellow megastar of the same generation, the film celebrates outsize talent while taking stock of something much quieter, an ache that isn’t necessarily remedied or even calmed by professional accomplishment. And like the Martin doc, which relies on the insights of one of his daughters, Lucy and Desi spends quality time with Arnaz and Ball’s firstborn, Lucie Arnaz Luckinbill. She offers searching and incisive testimony about her parents’ marriage and intertwined careers, citing “a cost to the success.” Her description of their final conversation, decades after they were each remarried, is wrenching in its simplicity. — Sheri Linden

The Tinder Swindler (Netflix)

In The Tinder Swindler, Simon Leviev (born Shimon Hayut) found women on Tinder, love-bombed them with lavish gifts and trips and then persuaded them to give him money by telling them he was in trouble — and never repaid them, leaving his victims with hundreds of thousands of dollars in debt. He would then take the money he’d gained from his deception to lure his next victim. “These women are all altruistic, empathetic women, and that’s what he trades on,” says Richards. “It’s a terrible thing when someone’s empathy and compassion for another is what’s exploited. But oftentimes, that’s at the heart of coercive control.”

Pernilla Sjoholm was one of Leviev’s victims, and she is still paying off her $45,000 debt. “For someone to be able to do that to a human, [the type of person whom] you would [think is] of lower intelligence, is something that I am very embarrassed about even today,” Sjoholm tells THR. “And this is why I also talk about it so much, because it could literally happen to anyone. I did not realize that [I was being manipulated] while I went through it, but of course now, looking back at it, I’m like, how could I not have seen it?”

Sjoholm says Leviev manipulated her by caring about what she liked, for example. “Being in Rome, I’m a sucker for history, so he had arranged a car just to take me through all the sightseeing spots,” she says, adding that he also acted as though he felt sorry for himself and pretended “he didn’t have any real friends and that I was the only person who actually cared, while other people just wanted to use him.” — Beatrice Verhoeven

We Feed People (NatGeo)

At some point in the last decade, my investment in mega-chef José Andrés ceased to be about someday visiting one of his many revered restaurants and became more about his winning a Nobel Peace Prize someday.

Andrés’ unlikely transition from culinary mastermind to culinary first responder is at the center of We Feed People, Ron Howard’s latest documentary collaboration with National Geographic Documentary Films after 2020’s Rebuilding Paradise. The Oscar-winning director has somewhat quietly become a curious and solid ultra-mainstream documentarian — the Ron Howard of documentaries, really — and We Feed People continues that journey. It captures enough of the methodology behind Andrés’ trajectory to be consistently interesting and it’s pragmatic enough not to be exclusively worshipful.

It would be easy and perhaps even accurate for Howard to treat Andrés as something of a gastronomical Avenger, selflessly zipping around the globe bringing paella to those in need, all while engaging on different social media platforms. And there’s some of that. Andrés is a gregarious, endlessly telegenic personality, with a telegenic wife and three telegenic daughters, and they’re all full of stories, usually with home video documentation, of Andrés’ larger-than-life approach to everything. About the most negative thing you’ll hear anybody in the documentary say about Andrés is that sometimes his daughters have to check Twitter to find out where he is at any given time.

But having altruistic intentions and having an altruistic idea aren’t the same as executing, and the things that Howard and his crew are most interested in documenting are the many steps between wanting to do good in the world and actually doing it. Yes, this is a documentary about one heroic man, but it’s much more a documentary about the bureaucracy of compassion. — D.F.

Best of The Hollywood Reporter