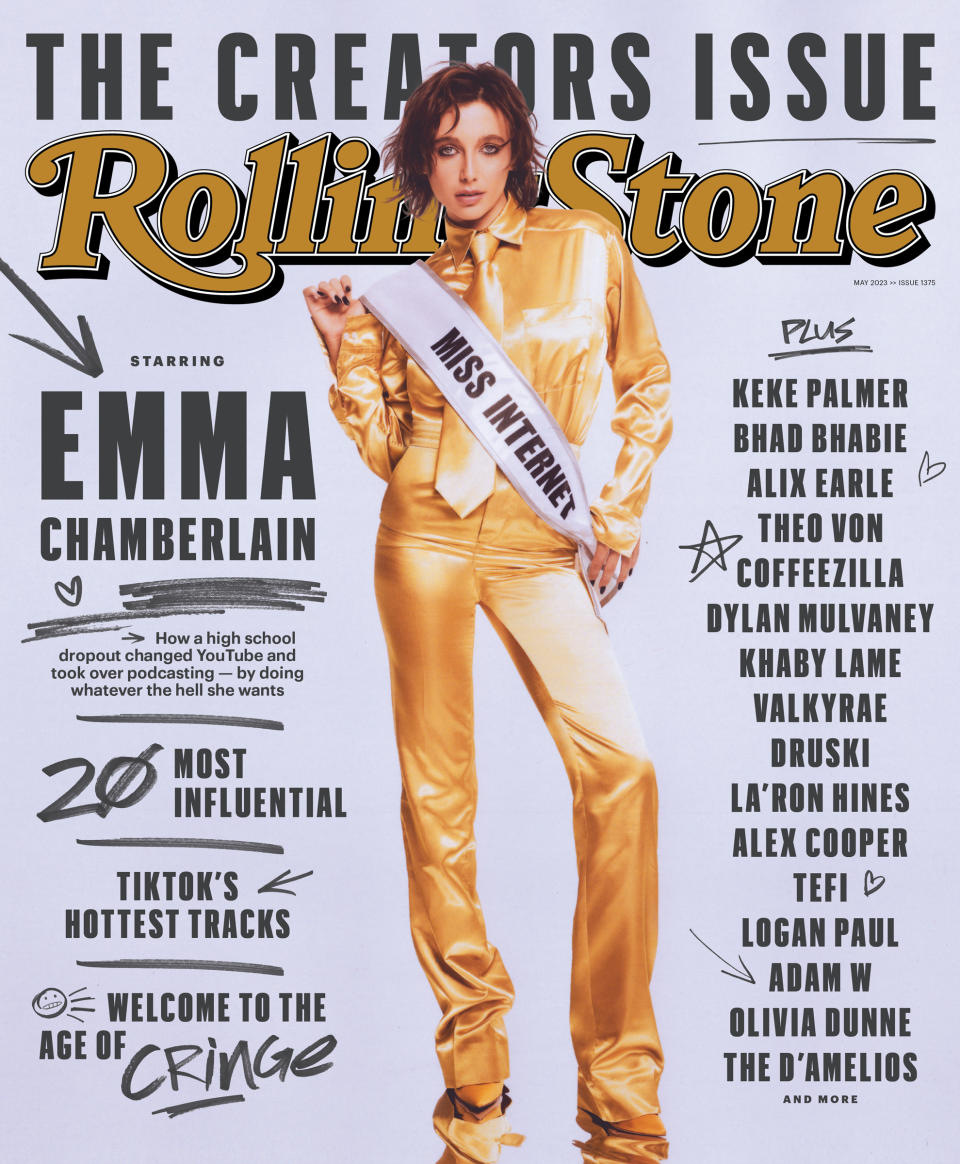

Emma Chamberlain Is in an ‘Existential Crisis 24/7.’ Let’s Get Into It

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

EMMA CHAMBERLAIN IS about to go off script. Which, to be clear, is totally fine with everyone here in this industrial warehouse in downtown Los Angeles on this sunny winter day. It’s fine with Chamberlain’s publicist. It’s fine with the representatives from Spotify, who are hosting the Stream On event in which Chamberlain is about to make her appearance. It’s fine with the woman who will be interviewing her, who gives off strong teleprompter vibes herself but who is apparently game to have Chamberlain just wing it. And it’s more than fine with Spotify’s top brass, who are probably well aware that Chamberlain’s Anything Goes was the third-most-listened-to podcast on their platform in 2022, and who are therefore primed to believe that, whatever she does, she must be doing something right.

Anyway, who needs scripts? Scripts can be awkward. And inauthentic. And cringe. Scripts are not part of the Emma Chamberlain brand, nor are they particularly beloved by the real Emma Chamberlain, who, in the past six years, has gone from a floundering high school sophomore to a person with one of the fastest-growing channels on YouTube to a red-carpet icon and podcast sensation and ostensible voice of her generation. And she has done all of this by very specifically — if also somewhat accidentally — not sticking to any particular script. At a time when all those other YouTube influencers were #blessed and living their “best life,” she showed up on the platform zitty and frenetic and irresistibly her awkward 16-year-old self (in one video dissecting Chamberlain’s oeuvre, viewers are counseled against taking a shot every time the poster says the word “relatable”; you’d get alcohol poisoning and die). Then, after Chamberlain had racked up millions of subscribers, made millions of dollars, and redefined a genre of new media that was still in the process of defining itself — after her way of editing and of being on camera had grown so popular as to become the de facto norm among Gen Z — she pulled back from YouTube and pivoted primarily to podcasts, where she has evolved from a teenager exploring such mysteries as why onions make you cry to a philosophizing young woman who can riff for an hour on mortality or creativity or the meaning of life (while still managing to squeeze in references to burps and poops).

More from Rolling Stone

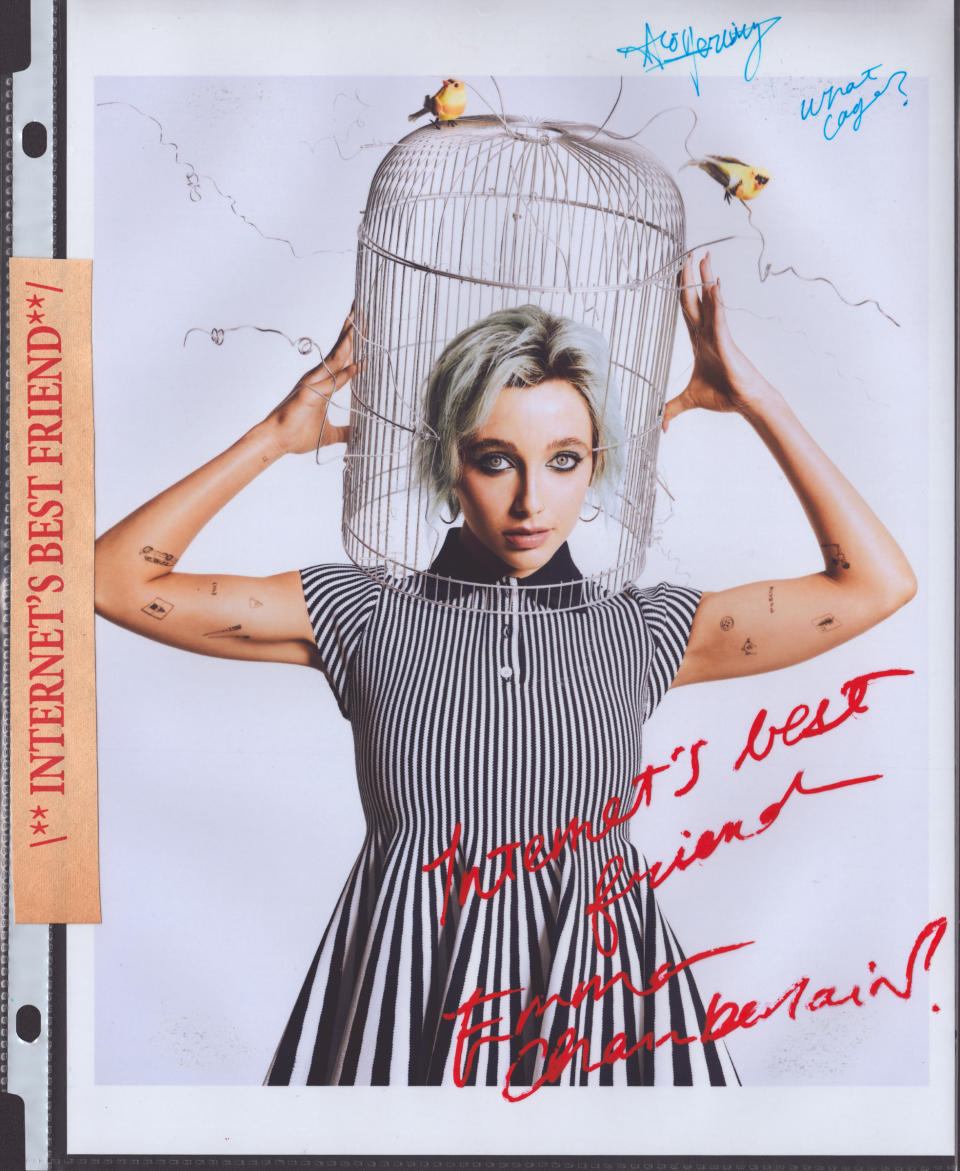

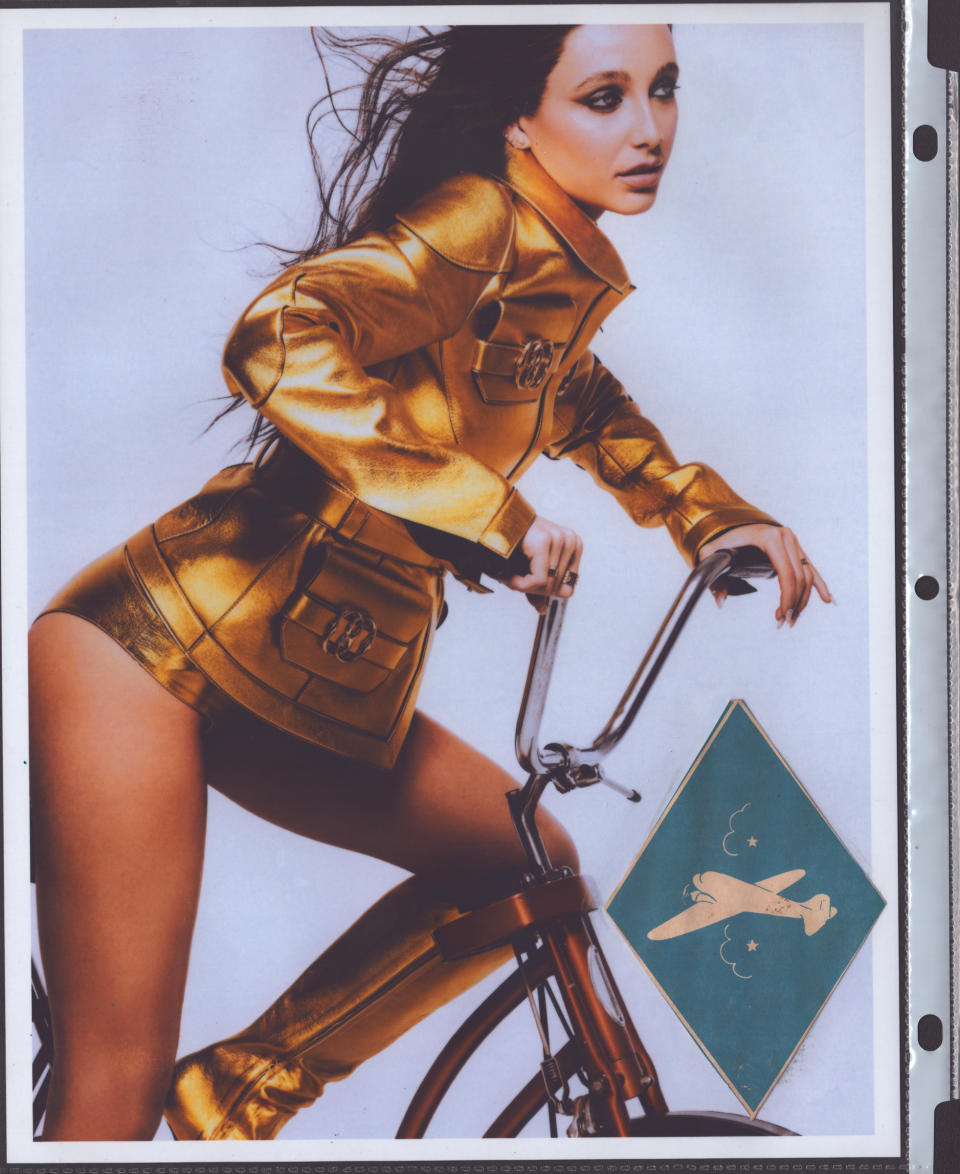

Go Behind the Scenes of Internet Golden Girl Emma Chamberlain's Rolling Stone Cover Shoot

Zealot or Savior? This U.S. Minister Is Training Rebels in a Civil War

J.D. Vance's 'Big Tech' Plan Conveniently Makes More Money for J.D. Vance: Report

Now, she’s leaning into the podcast’s video format, too, which in her case does not mean glam teams and impeccable lighting. It means setting up a camera in an upstairs room of her house, sinking into the sofa in front of it, tucking a blanket over her pajama’d legs, and talking from a bullet-point outline while her cats, Declan and Frankie, occasionally wander into the frame. If she gets completely distracted by a bug sighting or the need to scratch under her armpit and narrate why, she just goes with that flow. The flow is sort of the point. The flow is just how she’s wired. Content streams from her unbidden, freely, if not exactly for free.

“They gave me a script, but I don’t do scripts,” Chamberlain explains now, politely, to one of the many people popping in and out of her makeshift Spotify dressing room, created with curtains within the cavernous space. She has changed from the pajamas she wore on the ride over — a Beatles sweatshirt and cashmere-y pants — into a white shirt, an orange sweater vest, and a long denim skirt that seems to have an extraneous leg hole because … Oh, wait! It actually does have an extraneous leg hole. “My stylist was like, ‘Do you want me to tack this down so that it looks more like a skirt?’ ” she explains. “I was like, ‘No! I like the fact that it is confusing the masses.’ ” Outside her room, Swedish executives (Spotify is a Swedish company, if you didn’t know) lope about, bleary with jet lag as they make the rounds of the various other curtained-off spaces to glad-hand the talent. In the midst of the hubbub, Chamberlain has plopped into a chair across from the clothing rack and is holding forth with the giddiness of a theater kid backstage on opening night. When someone shares a video of their recent marriage proposal, she practically squeals with delight, then offers to direct the couple’s gender-reveal video when they have a kid (“It would end up being really weird, but it would also go to Sundance on accident”). When someone else mentions that she might enjoy attending the Brilliant Minds conference — a sort of genius Burning Man, from the sounds of it — she deems the prospect “epic.” Throughout all this effusion of goodwill, there are multiple check-ins about the script that she very much has not memorized and multiple assurances that, really, she doesn’t need to.

“I always get nervous before I do something live,” she admits to the assembled, not seeming nervous at all. “But I think if I memorize things, it does give deepfake sort of energy. I do so much better off the cuff. So I’m going to wing it. We’ll see how I do.” She smiles broadly. “We’ll see if I pull it off.”

I got sick of watching people I envied,” Chamberlain says. “What if I was someone to be friends with?

HERE’S ONE THING you need to know about Emma Chamberlain: She is constantly going off script and pulling it off. She is not operating off of some master plan. Across platforms, she may have more online followers than there are people on the continent of Australia, but she does not have it all figured out yet, and if you think she might, she will be the very first one to tell you you’re wrong. Or not wrong, per se — everyone is entitled to their opinions, as she’d tell you; differing viewpoints are opportunities for growth, as she’d say — but maybe not thinking clearly about how things have gone down for her and how she has navigated it all.

First of all, no one expected Chamberlain to drop out of high school at age 16, which isn’t the kind of thing that’s typically done in San Bruno, California, the Silicon Valley enclave where she was born in 2001 (four years before YouTube was founded above a pizzeria some eight miles away). It’s also not the kind of thing that’s typically done when one is a bubbly blonde, a former competitive cheerleader, and a member of the popular group at school, which Chamberlain says she was, if barely (“It never quite felt like a good fit”). Then again, that feeling of hanging on, of being the scholarship kid at a private girls school, of hearing that so-called friends who lived in mansions secretly made fun of the small apartments where she split time between her divorced parents (an artist dad and a flight-coordinator mom), well, that feeling didn’t help. She’d always been an anxious kid. She’d sucked her thumb and rubbed the ear of a stuffy called Biggie Big until she was nine, until right about the time that she’d started watching YouTube every day in the era of “David After Dentist” and “Charlie Bit My Finger” and FRED, a channel following the misadventures of a hyperactive six-year-old played by teenager Lucas Cruikshank (“The first YouTuber I loved,” she says). By the end of her sophomore year, she’d been working so hard to prove herself academically — “It’s like, if you’re smart, it doesn’t even matter how much money you have” — that she’d plunged herself into a deep depression.

You might need to be a member of Gen Z to understand what happened next, but here’s what did: Chamberlain failed her driver’s test, and the devastation was so total that she skipped out on even going to the last day of her sophomore year. Instead, she persuaded her dad to take her to San Francisco, where they filmed a video called “City Inspired Lookbook,” in which a guileless Chamberlain frolics about in various outfits. “That’s traumatic to watch,” she jokes of her feelings about the video now, but she readily admits that it gave her a sense of purpose then. Over that summer, she tasked herself with putting out one video a day, a breakneck pace that, she says, motivated her to get out of bed, helped her push her depression aside, and made her quickly tire of trying to curate a perfect image online. “I started out by doing that because I didn’t know what else to do,” she’d told me the day before the Spotify event, over sparkling water at the Sunset Tower Hotel. “You have to start by emulating what’s out there — you can’t come out of the gate with a unique idea. But what happened was I got so sick of that. I grew up watching a lot of people that I envied, like, ‘Oh, I envy your bedroom,’ or ‘I envy your makeup collection,’ or I envy this, or I envy that. And I was like, ‘What happens if I go the complete opposite direction? What about somebody who you don’t envy, who you just want to be friends with?’ ”

It wasn’t even that conscious at first. She’d be doing the influencer thing and would find herself internally mocking what she was doing, and then not so internally mocking it, like when she went on vacation and did the typical oh-my-God-look-at-my-gorgeous-view video, except hers was a view of a sidewalk. Or when she painted her own “Gucci” shirt, a perfect thumb in the eye of influencer-style conspicuous consumption. Famously, her first viral video was “We All Owe the Dollar Store an Apology,” a full-on parody of the high-end fashion-haul vlogs of the time, in which she feigned near-apoplectic delight at Frozen-themed Q-tips (“What more could you ask for in a product?”) and a fluffy pen (“Let me just take it out of its packaging so that you can see it in its full glory”) and a scarf covered with pictures of herbs (“I learned more about herbs from this scarf than I ever have in my entire life … You’re welcome”). The video got half a million views. Chamberlain’s first subscriber had been her dad. By the fall she had around 300,000 subscribers and was making a lot more than a high school allowance. If Jenna Marbles was that internet moment’s prankster and Logan Paul its bad boy, Chamberlain had become its quirky and beloved ingenue.

There was this public, unanimous decision that i was now annoying, cringe.

She went back to school in the fall, but when the administration forbade her from filming on campus, she — and her parents — decided that school was the thing that should go. She completed courses remotely so she could earn her degree, but in the meantime, barely six months after she posted the original lookbook video, the genre of anti-vlogging she’d stumbled into by just doing her thing was being emulated across YouTube: low production value, high relatability, a dash of the scatological and profane. In the Chamberlain oeuvre, outtakes are elevated, camera angles are unflattering, and she often cuts to video of herself in bed editing the main video with disdain. Rather than showing off some jet-set life, she took viewers along with her to Target or on a drive to get coffee. “I’m making an object that’s so easy to cook that literally cookbooks don’t even have recipes on how to cook this because it’s that easy,” she says in a video in which she (sort of) makes a burrito, after spending close to a full minute gagging from eating a hot pepper. Her idiosyncratic — though quickly popularized — editing style of rapid zooms and voice distortions and quick-flash text was, she says, just her way of trying to give shape and form to her own reactions. “It was basically replicating how my brain works, the way I was perceiving my footage,” she explains. “So if something would stick out to me, I would zoom in a little bit. I would emphasize. Taking a day that’s mundane and trying to make it interesting — that to me was an art form of my own. It was like, ‘How can I edit this so that people will want to watch me doing boring shit, basically?’ ” Soon, videos of Chamberlain doing boring shit and just going about her ordinary teenage life were some of YouTube’s most popular.

Which naturally means that the more she showed off that ordinary teenage life, and the more it resonated with people, the less ordinary it became. She moved to Los Angeles by herself at 17, and bought her first house at 18. She attended her first Paris Fashion Week and then was invited by Vogue to do red-carpet interviews at the 2021 Met Gala, where her first interview was with Anna Wintour (“There was a microphone issue, and I was like, ‘Fuck!’ I don’t think she was very impressed, but I think I won her back”). She went from repping Hollister to partnerships with Louis Vuitton and Cartier and Lancôme. In 2020, she started her own coffee company, Chamberlain Coffee, whose main marketing point is that it is the brainchild of Emma Chamberlain. At last year’s Met Gala — where her unfiltered response to Jack Harlow telling her “I love you” went viral — she found herself in the bathroom with Jenna Ortega, Billie Eilish, Kendall Jenner, and Hailey Bieber. Ortega was the only one she didn’t already personally know.

Obviously, backlash to her popularity and her choices has come in waves throughout this time. “What is so special about Emma Chamberlain?” is a not uncommon Google search. Just as she was blowing up on YouTube, she says, pressing herself against the side of the Tower Bar’s banquette and hunching over slightly, “there was just this public, unanimous decision that I was now annoying, cringe, all this. And I was getting hated on just for being me. Being hated in your school is one thing; you can go to a different school. Being hated on the internet is the whole fucking world. You can’t go anywhere. Talk about an existential crisis when there’s nowhere to hide.” Sometimes she responded by putting out a video in which she read people’s hate comments out loud. Sometimes she just “went into her shell,” says her dad, Michael. “It was really rough. It’s not like she went off the rails for a long period of time. But there have been many times when I’m like, ‘You know what? I don’t think this is good. There are not many people that can handle this in a way that leads to a healthy life.’ ”

I always say, ‘Listen, I don’t know what the fuck I’m talking about.’

There was also the sense that people the world over were watching and waiting for her to fuck up, which she inevitably did. A picture of her pulling back her eyes in the manner of the TikTok fox-eye trend was viewed as insensitive to Asian people. A makeover parody video, in which Chamberlain used foundation several shades too dark, was called out for appearing like blackface. This past March, a Twitter user posted an image of what seemed to be an advertisement for a “Personal Thank You Note From Emma in Instagram DM!” for $10,000 (or a payment plan of $902.58 per month), and derision swept the internet. (Her merch team quickly stepped in to say the offering had been mocked up as part of an internal test and that Chamberlain knew nothing about it.) “I’ve had multiple falling-outs of grace,” she says now. “That’s really hard for me, because if I intended to do something that was wrong or hurtful, fucking go off, tell me what’s up. I’m not a perfect person. Have I fucked up? Hell yes, I’ve fucked up. But there were a lot of times when things that I did maybe got taken out of context, twisted into [their] own narrative. And you feel out of control of your identity. I’m being generous by saying this shit has fucked with me on a mental level in so many ways.”

But honestly, it wasn’t just the backlash that fucked with her, it was also the adulation. As flattered as she was by the mimicry of her video style and content, it meant that suddenly she was doing what a lot of other people were doing — except that she couldn’t even do it anymore, not authentically. She wasn’t in high school. Her day-to-day existence wasn’t relatable, even really to her. And it seemed impossible to process the speed at which her life had completely changed and still keep up with the pace at which she was expected — by the masses if not the algorithm — to keep churning out content about it. Plus, few people had really had this type of celebrity before, a widespread fame forged outside any of the traditional channels and, initially at least, without any of the machinery or apparatus of celebrity to support it — the PR teams, the studios or record labels, the sense of how a career like hers was supposed to go. When the press came calling, she did not have the luxury of a new movie or album or book to talk about and hide behind. There was just … her, lobbing her real thoughts and experiences out into the world on a demanding, regular schedule.

“You’re so incredibly accessible to anyone at any given moment,” she says of internet stardom. “It’s dangerous. And everything is on a global scale, in a way.” By 19, the depression that her career had first staved off was being triggered by it. “You start to feel like, ‘Oh, fuck, this is getting boring,’ ” she says of her original anti-vlogger style. “I’m bored of this. Everyone else is getting bored of this.” It was hard to figure out how to evolve and to get ahead of her own trend — hard to view her real life as more than just raw material in need of commodification. And while there are any number of ways she could have dealt with that, what she did was maybe one of the last things anyone would have expected from an erstwhile teenage YouTube celebrity: Chamberlain went deep.

IF ONE WERE, in one’s mind, to craft a perfect place of quiet contemplation, monastic bliss, and midcentury mystique, one could certainly do no better than Chamberlain’s home in the Los Angeles hills. Paneled skylights, exposed beams, and marble surfaces commingle to soothe the senses. Everywhere one’s eyes alight feels clean, curated, organic, and Zen. After an Architectural Digest video tour was released last year, social media exploded with Tweets like, “Girls don’t want boyfriends they want Emma Chamberlain’s kitchen.”

Her closet is not too shabby either, especially because it’s not actually a “closet” but a whole repurposed room in which, a few hours before the Spotify event, Chamberlain can be found sitting on a puffy, striped toadstool of a seat in front of a sleek vanity as one very stylish man blow-dries and fluffs her hair and two very stylish women work on her makeup. Outside the window, light glints off the pool, and a stone waterfall tinkles. Inside, couture hangs with gallery-like precision as Chamberlain explains how she got here — “here” being not this room-size closet, but rather this current place in her mind, which unlike her surroundings, has never been, and will likely never be, a place of respite and calm.

The thing is, she’s long since given up on thinking that she can will herself into a place of nirvana via some sort of relationship with millions of people she’s never actually met (“When I look at myself as an online object, in a literal way, I fully, immediately, severely dissociate as a response”). She’s long since abandoned the idea that money could heal her woes (“It only really matters to a certain point, and that point is much lower than you would expect; beyond that, it brings you nothing”). She’s well aware that the body dysmorphia she’s struggled with since she was a child will probably always be with her (“Sometimes it’s a huge issue, and I’m hyper-obsessed about how I look; having to be photographed can trigger me”). And she’s long since abandoned any illusion that fame could pull her out of her own head and deposit her into another one. “I expected to go to the Met Gala or meet somebody I idolized and to reach a new level of happiness that I never felt before,” she says at the Sunset Tower bar. “What I found was I felt that same level of happiness as when I won a cheer competition in middle school. I assumed that if I reached the level that I’m at now, I would be sort of invincible and my mind would be expanded, and I’d experience emotions I’d never experienced. I was expecting to feel a feeling that literally doesn’t exist. It’s like flying to Mars and expecting to find a new color.”

News flash: There are no new colors. There are no new bodies. There are no new heads. There’s just her own, in which, she says, “I’m constantly finding myself in an existential crisis, 24/7, all the time.” Even now. Especially now that the past five years of her life have warp-sped her through the socio-economic spectrum, through the ranks of celebrity, and through such an extensive amount of surreal real-life experience. Especially now that she’s given herself permission to slow the fuck down and reflect on all of this, and has turned that reflection into her actual job.

Which means that it behooves her to have questions and not have answers. My sense of a normal day in the life of Emma Chamberlain? She wakes up and thinks. She has coffee and thinks. She works out and thinks. She looks at mood boards and thinks. She drives around and thinks. She makes voice memos and creates bullet points and thinks them through out loud in her upstairs room with a camera rolling. A few days before we first met, she’d done a podcast episode titled “Is Creativity Dead?” A few days later, she’d released “We Know Nothing.” And if you think whatever ideas she posited in the former might be canceled out by the latter, that’s exactly the sort of thing that she wants you to ponder. The thinking-not-knowing is where her instincts have taken her. The thinking-not-knowing is where she’s decided she should psychologically be. “I’m an overthinker,” she says. “I don’t necessarily fully have a grasp on my identity, but that’s part of my identity. I feel comfortable there.”

Indeed, few have ever discussed their own mental struggles in such a bright and cheery way as Chamberlain does on Anything Goes. Or talked about their body dysmorphia with such self-acceptance. Or given advice with so many caveats. “I always say, ‘Listen, I don’t know what the fuck I’m talking about.’ If you’re like, ‘Emma, that’s not true,’ I’m like, ‘OK, I know.’ I’m the first one to say that I don’t know. But I don’t feel like I need to necessarily read four books to put my opinion out there,” she says, summing up her generation (and part of her appeal to that generation) in 18 words. “Even just coming to three different possible conclusions could make me feel satisfied.”

Not that satisfaction comes particularly easily to an overthinker. At the hotel bar, Chamberlain spends a long time talking about her relationship with singer-songwriter Tucker Pillsbury — known professionally as Role Model — and how their happiness, counterintuitively, is also the source of much of her anxiety. “I will say right now, my anxiety has been very bad,” she says. “I think it’s scary for me at times to rely on people so heavily, whether it’s my parents or Tucker. I mean, because of my circumstance, there are so few people in my life who I truly feel I can trust that the fear of anything happening to them is unbearable to me.” She tells me that her social circle now consists of exactly six people: her friend Amanda, who she meets for yoga; her stylist Jared Ellner and his boyfriend, Owen, who she meets for shopping; her parents, who are “very nonjudgmental, very open-minded”; and Pillsbury, who “knows all my flaws, all my shortcomings” and still sticks around. After years of fan speculation, Chamberlain and Pillsbury recently took their relationship public, something Chamberlain previously had imagined that she’d never do. “I know it’s incredibly vulnerable to say out loud, but Tucker is a complete rock for me,” she says. “You know when you’re with somebody, and it becomes like you’re almost cellularly bonded? I mean, to be honest, I don’t feel impulsive saying that I would marry him, because just being around him brings me back to earth. Seeing the way that he carries himself, I’m like, ‘All right, I’m fucking losing it, and there’s no reason to be losing it.’ ” Plus, she adds, “We don’t enable each other. If I were to show Tucker something I did creatively, and he didn’t agree, he would fucking tell me. And he has.”

At some point this year, Chamberlain plans to start inviting guests onto the podcast for the first time, people she hopes will disagree with her too. “I am excited about talking to people who are specialists in topics that I have discussed in the past,” she says. “I’m excited to get into the thick of it and have somebody be like, ‘No, Emma, you’re actually wrong,’ because when I’m wrong, it’s almost like correcting. It’s like putting a puzzle piece in — but then also knowing that my mind might change again tomorrow.”

In the meantime, she concedes, her mind might change about making more YouTube videos. “If I’m in the mood to film some shit, I’m going to do it,” she says at one point. “But God knows what that’s going to be. It’s not going to be like anything I’ve ever done.” Maybe she’ll make documentaries. Maybe she’ll edit films. Maybe, she says, she’ll just retreat, open a coffee shop, settle down, have a few kids, an experience she imagines to be “humbling” and full of wonder and entirely incomprehensible, so of course it’s in her lane.

It’s getting dark outside the windows of the bar by the time Chamberlain starts indicating that she should probably go. Her dad is in town, and she plans to cook a vegetarian dinner for him. “I have to make him pesto pasta with a side of some sort of vegetable, probably Brussels sprouts,” she says. Afterward, she suspects that Pillsbury will come over for one of the jam sessions he and her dad like to have. “We call it band practice, where I play the drums, Tucker plays acoustic guitar, my dad will play electric,” she says of their music, which, she clarifies is “never to be released, only to be done in the privacy of my back room.” She laughs. “I’m terrible.”

But, you know, sometimes you just need to jam, to go by instinct, to follow what feels right. There’s still so much to ponder, so many questions to ask. Still so many unscripted and unscriptable answers, and Chamberlain is here for that. The Spotify appearance the next day won’t go entirely as (not) planned — there will be moments when she repeats herself or gets tangled up in her thoughts — but sometimes that’s just the way it goes when the answers aren’t written. “I didn’t nail it,” Chamberlain will say, not unhappily, as she exits the stage. “That was one of my worst performances. But it came from a real place.” As long as it comes from a real place, it’s fine, really. It really is fine. That’s the one thing she knows for sure.

Production Credits

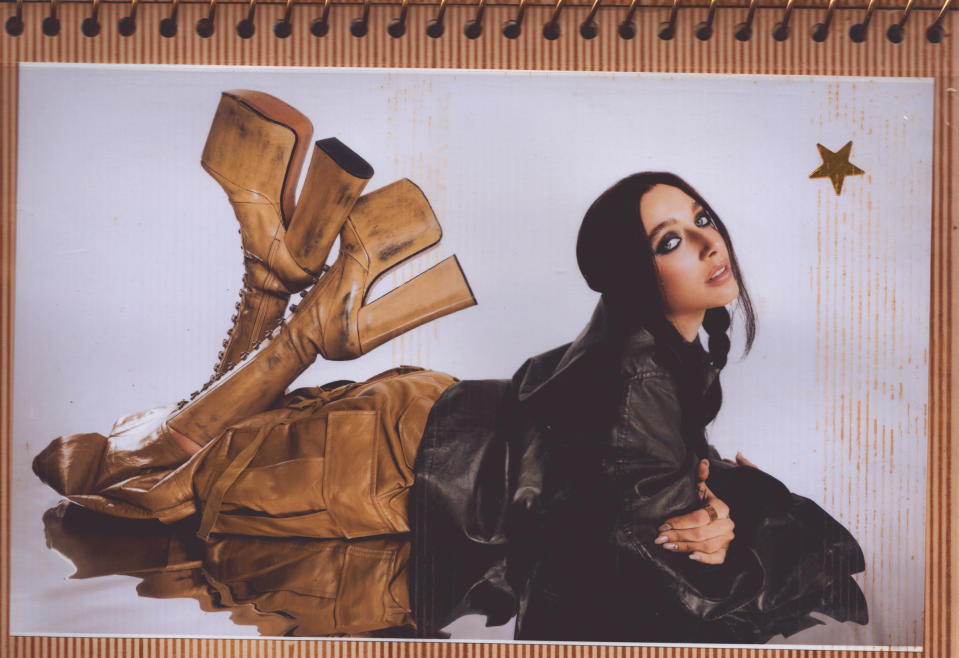

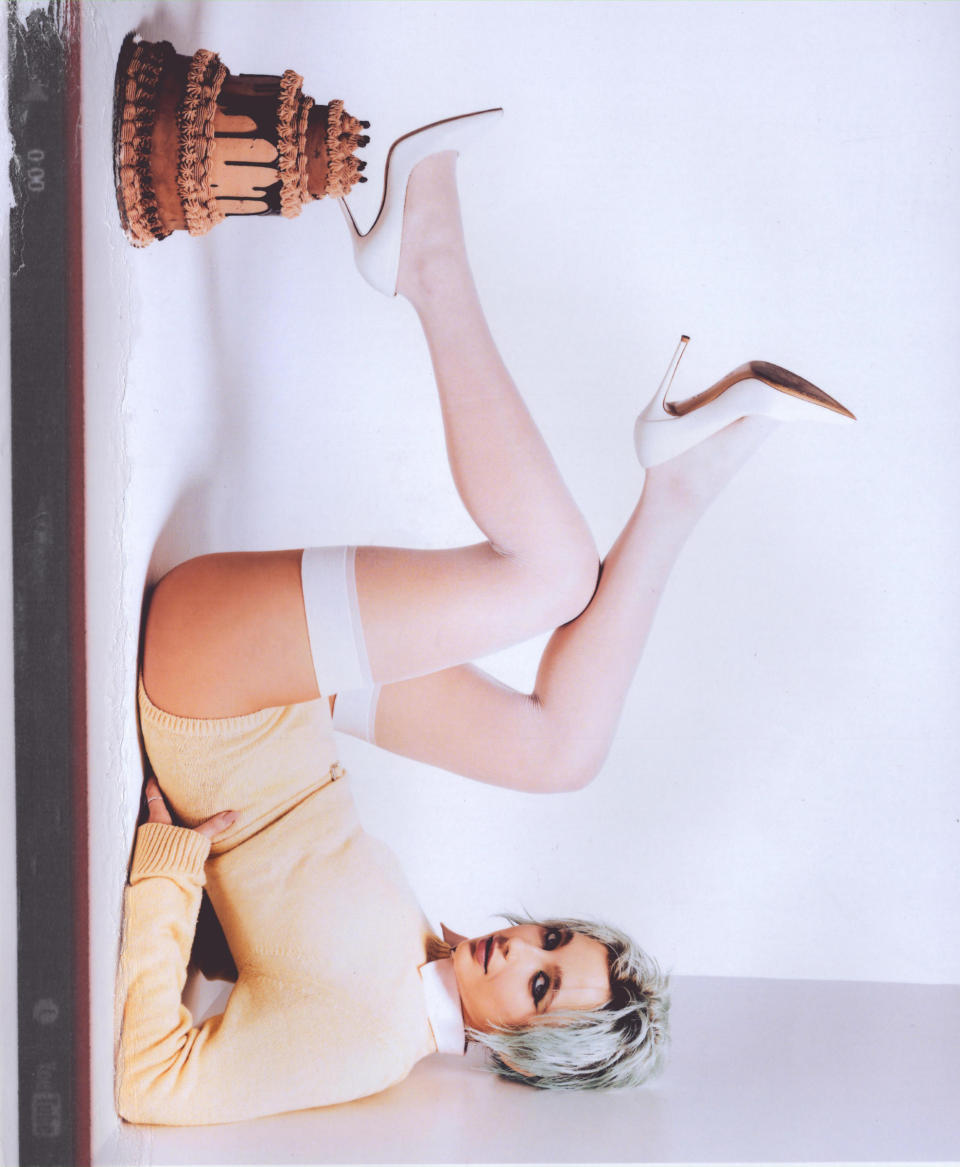

Produced by RHIANNA RULE. Photography direction by EMMA REEVES. Styling by JARED ELLNER at A-FRAME.

Hair by SAMI KNIGHT using FEKKAI at A-FRAME. Makeup by ALEXANDRA FRENCH at A-FRAME. Nails by THUY NGUYEN at A-FRAME. Tailoring by ALVARD BAZIKYAN. Set design by OLIVIA GILES at JONES MGMT. Production assistance by PETER GIANG and JACK CLARKE. Lighting technician KURT MANGUM. Photography assistance by LEA GARN and BREYER FLOYD. Digital Technician BRIAN KENDALL. Styling assistance by JESS MCATEE and BROOKE FIGLER. Hair styling assistance by DYLAN AMBRO. Set design assistance by OLIVIA KESS. Photographed at SMASHBOX STUDIOS

Best of Rolling Stone