Eleanor Coppola On The Fundamental Truth Of Movie Production: “It’s Never Easy” – Deadline Disruptors

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

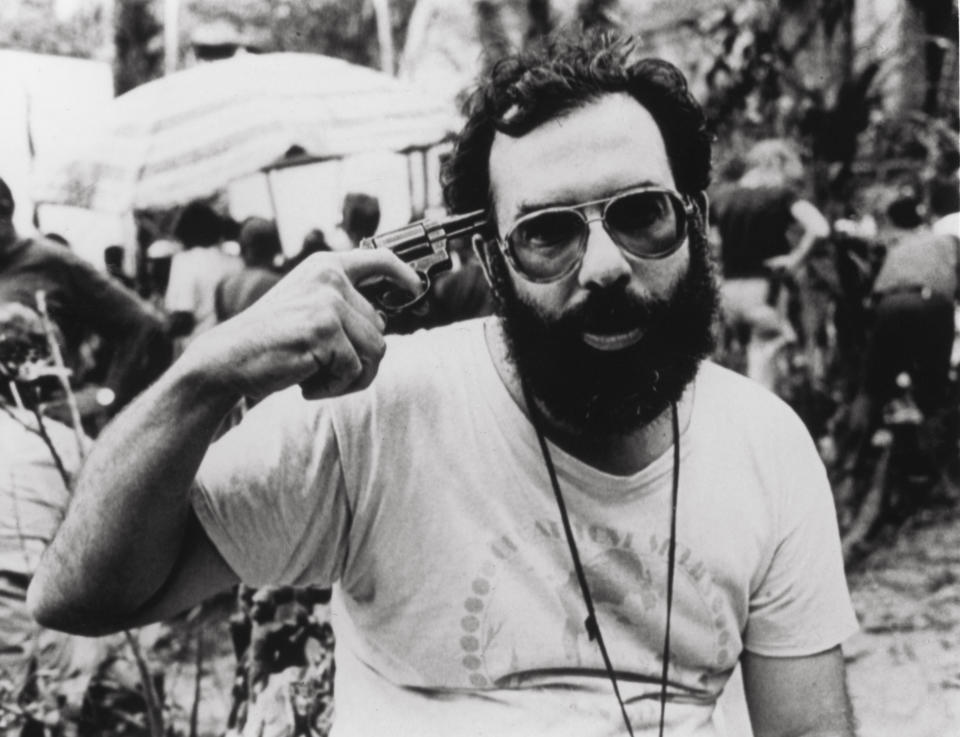

“Francis feels very frustrated,” wrote Eleanor Coppola in Notes: The Making of Apocalypse Now. “He gathers up his Oscars and throws them out the window. The children pick up the pieces in the back yard. Four of the five are broken.” The shoot for Francis Ford Coppola’s Vietnam epic had yet to even begin—the director was still trying to cast the key roles of Willard and Kurtz. Steve McQueen, Al Pacino, Jimmy Caan, Robert Redford and even Marlon Brando had all turned him down. Their reasons bounced between keeping kids in school, fears about getting sick in the Philippines and, of course, money. This is just the start of a book crafted from Eleanor Coppola’s three-year diaries kept during production on Apocalypse Now.

More from Deadline

The entire Coppola family had moved to the Philippines—Francis, Eleanor and their three children, Gian-Carlo, Roman and Sofia—and Eleanor had been additionally tasked with gathering documentary footage of the shoot that could be used by the United Artists marketing department. “I don’t know if [Francis] is just trying to keep me busy or if he wants to avoid the addition of a professional crew,” she wrote. “Maybe both.”

Whatever the reason, Eleanor and her documentary crew soon bore witness to the complex and chaotic shoot of a movie that seemed destined to fall apart at any moment. In 1991 she teamed up with Fax Bahr and George Hickenlooper to direct Hearts of Darkness: A Filmmaker’s Apocalypse, based on the footage she shot, which has become perhaps the definitive document of a major motion picture production. It is both a cautionary tale and an existential salve for filmmakers, who talk regularly about its impact—if one of the greatest movies of all time can suffer from such troubled seas on its way into cinemas, perhaps that struggle is a necessary part of the creative process.

Zoetrope/United Artists/REX/Shutterstock

“Francis had this incredible ability to keep going on Apocalypse Now,” Eleanor Coppola reflects now. “There were times when I would just say to him, ‘You know what? We can just go home. You can just say this one didn’t work out. You’ve made fabulous films before, and you can again. Just let this one go.’ But that kind of determination was a big lesson in living my life.”

We are sitting on the veranda of the Coppolas’ Niebaum mansion, on the Inglenook Winery in Rutherford, California, which Francis purchased in 1975 with the proceeds from The Godfather. It’s from one of these windows that he likely jettisoned those Academy Awards (since repaired). But as the sun beats down on the beautiful, rainbow-colored gardens around us, the estate seems to serve as a tantalizing reminder of the rewards that can come from exceptional creative endeavor; and of what could be lost when it doesn’t work out.

Zm/Zoetrope/REX/Shutterstock

Eleanor Jessie Neil married Francis Ford Coppola in 1963, after they’d met on the set of one of the director’s early features, Dementia 13, where she worked in the art department. It was a shotgun wedding, hastily arranged in Las Vegas when Eleanor became pregnant. After the wedding, she met Francis’s parents, and “I learned he was from generations of Italian men who believed a woman’s life work was caring for home and children and supporting her husband’s career”, she wrote in her 2008 memoir, Notes on a Life. “Francis knew I had artistic aspirations, but expected they could be pursued at home in my spare time.”

She earns a place on our list of disruptors precisely because those aspirations have never abated. This year, at the age of 81, Coppola has become the oldest American director ever to make a dramatic feature debut. Paris Can Wait, starring Diane Lane and Arnaud Viard, premiered at the Toronto Film Festival in September, ahead of a U.S. release last week, making Eleanor the latest, and perhaps least likely, addition to the Coppola filmmaking dynasty.

TIFF

Born of a real road trip Eleanor took after a visit to the Cannes Film Festival with Francis—when a head cold prevented her from departing Nice by plane, as scheduled, and she instead drove to Paris with a French business associate of her husband’s—the film follows Lane’s character, Anne, as she sets off for what she expects to be a seven-hour direct journey to the French capital. But her traveling companion Jacques (Viard) is in no hurry to return, and so he side-tracks Anne into any number of bistros, inns and picturesque sights, on a ride that takes several days and reawakens Anne’s spirits.

“When I came back from this trip, I was telling a friend the story, and we were laughing about it,” Coppola recalls. “She said, ‘Oh, that’s the movie I want to see.’ I could never have imagined it, but some little lightbulb went off. I’d published my book that year and I was in the mood to write, so I got a program for my computer and set off. I began to really see the fun of making fiction, which is different than documentary.”

Different, but not entirely. Aside from the road trip itself, Anne is a keen photographer with an interest in textiles—just like Eleanor—and she’s married to a film producer, whose work seems to consume him. “I got to sort of play out aspects of myself,” she admits. “Little quirks I have. I thought it was important to make her specific and particular so that we got to know her. I know more about myself than anybody else, so I used those aspects.”

The fiction is layered on top—in the film, there’s a flirtation with Jacques that never occurred, and Jacques himself turns out to be carrying a few secrets that she insists add a layer of drama missing from her real companion. But the film is as honest as Eleanor Coppola has ever been, in her writing, in her documentary filmmaking, and in her life.

Roger Arpajou/A+E Studios/REX/Shutterstock

In retrospect, it’s hard not to wonder if this journey into narrative cinema wasn’t always in the cards. “The beginning of the film idea for me was certainly documenting Apocalypse Now,” she says. “I had no idea. I’d made some little art films in the early ’70s, but when I got this camera in the Philippines I was just mesmerized, looking through the viewfinder. I really responded to that, so I made different documentaries, because I always loved to shoot.”

But fiction film never crossed her mind, she says. “And it was a little intimidating, because here I was living with two Oscar-winning screenwriters. But something happens to you in your 70s, I think, that you just suddenly realize you’re not going to live forever, and you kind of adopt a ‘why the heck not?’ attitude. What had I got to lose?”

It was Francis who suggested, one morning over breakfast, that Eleanor might consider directing the film herself. She had struggled to find a director whose aesthetic sensibilities felt right. But his suggestion carried with it an additional pressure—not just that it required Eleanor to learn a new skillset, but that it demanded of financiers that they take a chance on an untested director. And Eleanor was determined that she should only make the film if an outside party believed in the film enough to put up the budget.

TIFF

“It was a hard sell,” she admits. “It took six years to raise the money, because I don’t have any aliens, nobody dies, there are no guns and no car crashes. There was nothing that an investor wants to invest in. No sex, no violence. And I was a woman who had never directed a feature before. I had a lot of points against me.”

The challenges started with casting, as she worked to raise finance. “I had interviewed another actress I really liked,” Eleanor recalls. “I wanted the woman to be about 50, and by the time I’d raised the money, she was in her 60s. Diane Lane had been 44, and was suddenly 50. These kinds of things moved and shifted in the course of time. When it finally worked out, and Diane committed, it still took another year, because I thought I could raise the money on Diane, who is such a terrific actress. But no, I had to have somebody play the husband.”

The financiers had given Eleanor a list of four actors they thought could play Anne’s film producer husband. She cast one of them, only to have him drop out two weeks before he was to be called to set. “I called every actor that Francis had ever worked with, in a panic,” Eleanor recalls. “I had a list that I went through. Nobody was available. By chance, Alec called Francis and said, ‘Would you do me a favor?’ Francis said, ‘I’m sorry, I can’t. But would you do me a favor?’”

Sony Pictures Classics

Just as Francis had contended with a chorus of refusals as he cast Apocalypse Now—even from Brando, who would later consent to play Kurtz—so Baldwin, too, declined. “Diane was instrumental in convincing him, because they’d worked together on a play 20 years ago. She wrote him a note and said, ‘You should get over here and help these women make this movie.’ And he showed up.”

The cast, she says, “turned out to be the people I wanted, but it took a while to get there”. It’s hard to imagine Apocalypse Now, with Al Pacino as Willard and Steve McQueen as Kurtz. For Eleanor, this marriage of creative vision and the flexibility to roll with the punches has marked her filmmaking experience, too. “I think it gave me a great appreciation for everything my family goes through on their movies,” says Coppola. “There are disappointments, but also surprises at the same time that are caused by the difficulties. And all of these are things you learn when you just don’t give up. In your most desperate moments, you figure out how to be as creative as possible, and it’s a part of the process you never really think about when you’re writing and planning.”

Her biggest lesson of the shoot? “That no matter how well you prepare, there are these things that can happen that you can’t be prepared for. You have to create a solution in the situation.” From the woman who tracked the making of Apocalypse Now, and has accompanied Francis, Roman and Sofia Coppola on any number of film shoots, this sounds faintly amusing, and I tell her so. “Well, they bowled me over when they happened to me, and it wasn’t so funny,” she laughs. “But every time there’s a crisis on a film, and you’re doing the documentary, you go get it. It’s great material. So it was the flipside of documentary-making, because you now have to solve all these problems.”

A+E Studios/REX/Shutterstock

Motherhood, she says, prepared her for those challenges in ways she hadn’t expected. “You’re always trying to get your kids not to fight, and thinking about them. Are they cold? Bring their sweater. Bring their shoes. You are focused on tending to the needs of the people around you.” Paris Can Wait was shot in 28 days—“And I don’t think I appreciated the nitty-gritty of it before,” Eleanor says. “‘What do you mean I can’t have more days to shoot?’ I guess I was used to being with Francis, planning 168 days in the Philippines, and then it’s the 200th day, and we’re still there.”

That a warm-hearted, meandering road-trip movie through the picturesque scenery of rural France could compare—on any level—to the fevered shoot of a war epic in the Philippines speaks to a universal truth about film production that so often goes unrecognized.

“It’s never easy,” Eleanor says.

In the press, perhaps conditioned by movie marketing that paints picture-perfect visions of cast and crew harmony, artistic pleasure, and a sense that everything happened as it was meant to, we are suspicious of reports of troubled productions. But isn’t film history littered with classics that seemed destined to crumble before the final hurdle? And aren’t the greatest directors the very ones who lean into the madness as they journey up the river?

“I’ve pondered that question a lot,” says Eleanor Coppola. “There’s something that I think comes from pushing yourself to the limit. If things are difficult, then you have your challenge. You have to expand your thinking and go further and deeper than you intended to go. When I got into these tight spots with my project, and after four or five years of development with people saying, ‘You’re never going to make this film,’ there was a part of me that knew: I wasn’t going to stop.”

Best of Deadline

2023 Premiere Dates For New & Returning Series On Broadcast, Cable & Streaming

TV Cancellations Photo Gallery: Series Ending In 2023 & Beyond

Sign up for Deadline's Newsletter. For the latest news, follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.