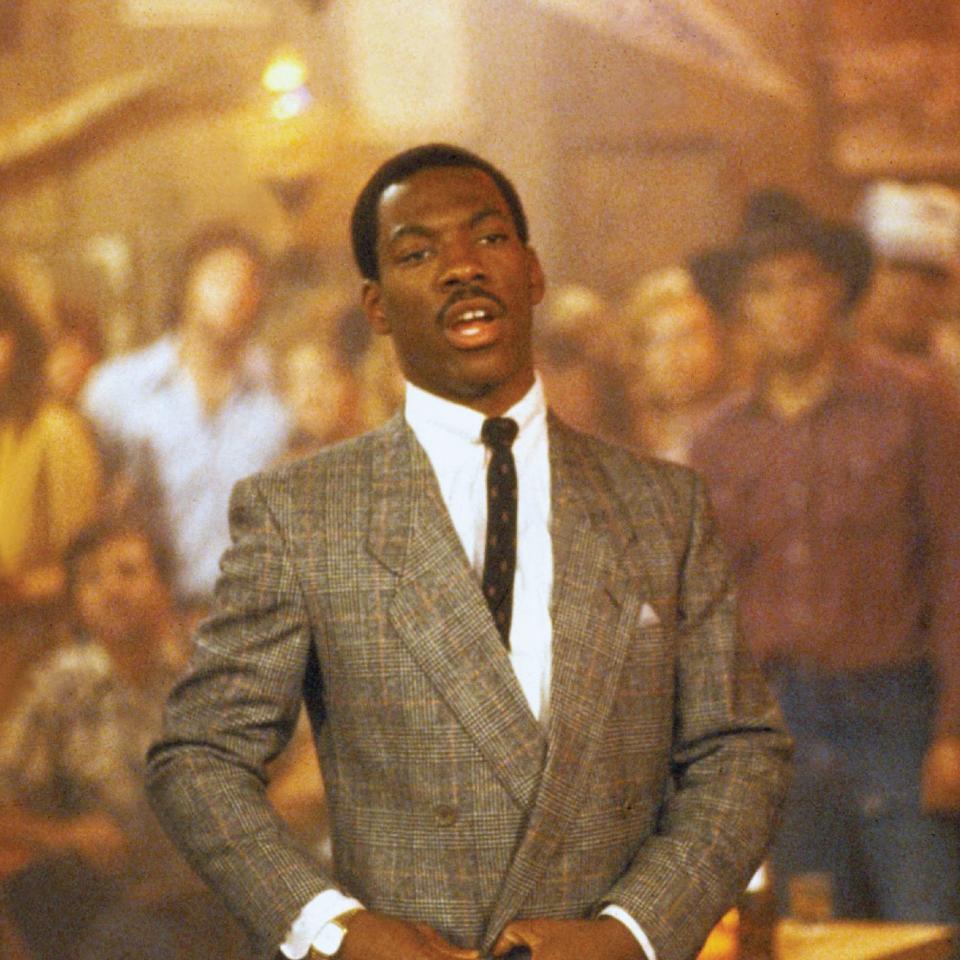

How Eddie Murphy changed mainstream movies, one hit at a time

The following is an excerpt from Hollywood Black: The Stars, the Films, the Filmmakers, by Donald Bogle, which offers a sweeping overview of black Americans in film, from the silent era through Black Panther. This selection charts the rise of Eddie Murphy as a movie star in the 1980s. Hollywood Black publishes Tuesday and is

—

In 1982, mainstream movies were jolted by the arrival of Eddie Murphy. In many respects, Richard Pryor had cleared the way for Murphy’s ascent, preparing audiences for an iconoclastic, tough-talking, profane African American comedian. Born in Brooklyn in 1961, Murphy had shot to fame as a cast member of TV’s Saturday Night Live, often creating controversial characters, such as the pimp Velvet Jones, the convict Tyrone Green, and the angry Gumpy. He also did a satirical take-off on the character Buckwheat from the Our Gang series.

He was soon off and running in a series of hit movies, starting in Walter Hill’s fast-moving 1982 action-comedy 48 Hrs. As the prison inmate Reggie Hammond, who is sprung from jail to help white cop Jack Cates (Nick Nolte) track down two killers, Murphy was quick on the draw and able to hold the screen with the same ease and dexterity as his far more experienced costar. Most believed the scene of Reggie, posing as a police officer in a redneck bar, spotlighted the comic at his assured best. Even if you don’t believe in the scene (that he uses his badge to strike fear into the dopey crowd), it was hard not to enjoy the way his brash, hip black character uses his street smarts to outwit them.

Criticized for its violence in its day, for later generations 48 Hrs. also had a misogynistic streak as Nolte battles it out with his girlfriend (Annette O’Toole) and Murphy’s character has a fling with a young African American woman (Olivia Brown), whom he appears to wrongly regard as a whore. But that’s not all that could make contemporary audiences in the twenty-first century squirm in their seats. As Nolte’s character hurls racist slurs and epithets at Murphy, moviegoers are to laugh at the remarks, as if we’re all adult enough now to realize it’s just talk, that’s all. At the close of the action, Cates makes a halfhearted apology to Hammond, the way a macho tough guy might. But viewers still may feel uncomfortable with this aspect of a very popular film (the seventh highest-grossing movie of 1982). The film also again pushed the theme of interracial male bonding. It is considered the first of the white/black buddy cop pictures, a new genre that continued throughout the 1980s. Eight years later, a disjointed sequel appeared, Another 48 Hrs.

Murphy’s next film was John Landis’s Trading Places, which also toyed with the bonding theme while exploring comically the long-debated theory of heredity versus environment in determining one’s place in society. Here two rather sinister older white men (Ralph Bellamy and Don Ameche) manipulate two young men to test the theory. One is white investment broker Louis Winthorpe (Dan Aykroyd); the other, a wily black conman, Billy Ray Valentine (Murphy). Winthorpe is stripped of his class and status; Billy is elevated to a position of wealth and privilege for which he is not prepared.

An unsettling strain of possible racism runs through the depiction of the black character, forever crude and coarse, forever trying to get over. Murphy does not always work against the script to bring some nuance to his character, and, frankly, at times with his broad grin and popping eyes, his characterization bordered on caricature. Nonetheless, moviegoers responded to his bodacious confidence, assertiveness, and refusal to be racially submissive, all of which did infuse his character with a different dimension. Let’s hope!

Murphy’s biggest hit of the era was another action comedy, Martin Brest’s Beverly Hills Cop (1984). Here he played a Detroit police officer, Axel Foley, who goes to Beverly Hills in search of the killers of his best friend. Underlying the story line was the contrast of high and low: the plush, ritzy world of Beverly Hills as a backdrop for the gritty street smarts of the dude from Detroit. The Beverly Hills police force doesn’t know what to make of Foley, but in time two white cops, Detective Billy Rosewood (Judge Reinhold) and Sergeant John Taggart (John Ashton), bond with him. Once again, Murphy’s appeal was his brash confidence, which enabled him to demolish the pretensions of others, and to surprise the unsuspecting with his savvy intelligence and uncanny awareness of the world. For most, it was an enjoyably formulaic old-style Hollywood film, but with a new brand of hero.

Interestingly enough, Murphy didn’t have a significant romantic love interest. His relationship with a young white woman who runs a gallery in Beverly Hills is strictly platonic, something that would not have been the case had Sylvester Stallone (originally considered for the role of Axel) played the character—leading to questions about Hollywood’s ongoing fear of strong, sexual, romantic African American men. The same kind of questions had been asked about Poitier characters. Beverly Hills Cop, however, thrust Murphy into the superstar category. The number one box-office hit of 1984, it spawned two sequels, Beverly Hills Cop II in 1987 and Beverly Hills Cop III in 1994, neither of which matched the appeal of the original.

Murphy’s career continued on a roll with the 1988 comedy Coming to America. But Murphy must have considered the criticism of his screen characters, because he appeared to take more control over his image, including having an on-screen romance this time around. Murphy played an African prince, Akeem (in a totally fake and preposterous view of African culture), who comes to America—Queens, New York, to be exact—in search of a bride. James Earl Jones and the terrific Madge Sinclair portrayed his parents, and Arsenio Hall (a real-life friend of Murphy’s) played his sidekick.

Also in the cast were Cuba Gooding Jr., Samuel L. Jackson, John Amos, Eric La Salle, Calvin Lockhart, Shari Headley, Garcelle Beauvais, and Allison Dean, as well as cameo appearances by Trading Places costars Ralph Bellamy and Don Ameche. But Murphy was the centerpiece, playing three other characters in addition to Prince Akeem, revealing the actor’s great skill at timing and parody. Director John Landis had the good sense to stay out of Murphy’s way. The studio, Paramount, reportedly had not been enthusiastic in backing this basically black-cast film. Would Murphy’s large white constituency go to see it? The answer was yes. Coming to America was another hit that grossed $160 million worldwide. It proved that moviegoers could be far ahead—in their views of what a black movie hero could be—of those who ran the studios.

—

Reprinted with permission from HOLLYWOOD BLACK: The Stars, The Films, The Filmmakers © 2019 by Donald Bogle, Running Press in partnership with Turner Classic Movies