During the coronavirus crisis, can live-streaming save the music industry?

As the touring industry grinds to a halt due to the worldwide coronavirus outbreak, leaving both musicians and fans stuck at home, A-list artists like Garth Brooks, Chris Martin, John Legend, Jennifer Hudson, Jewel, and Keith Urban are attempting to fill the void with livestreams. Some artists are broadcasting these intimate living room concerts for charitable initiatives, while others are seemingly just hopping on Instagram Live on a whim. But what about struggling indie and mid-level artists, the ones that don’t exactly have rock-star bank accounts? With their gigging plans now on indefinite hold, is it possible that streaming could actually be a viable source of income for them?

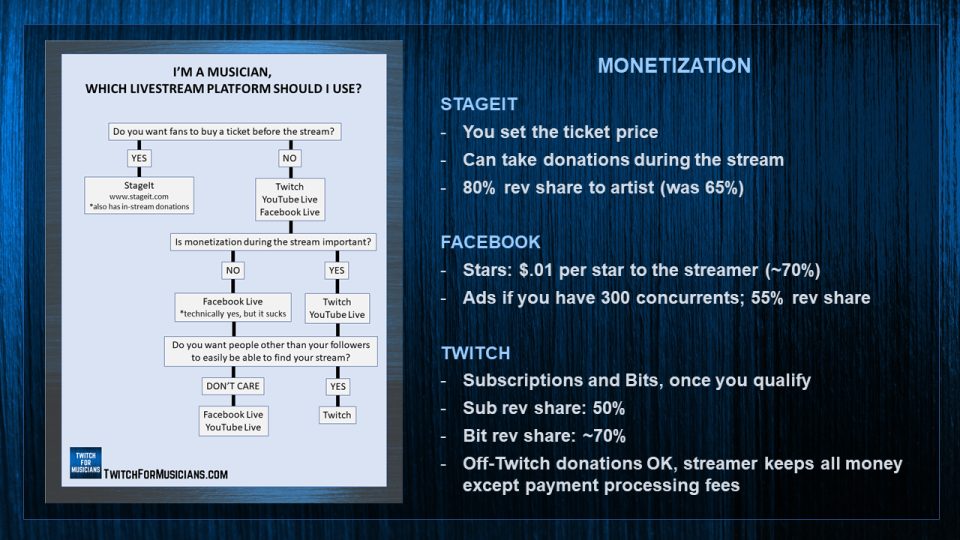

While there are opportunities for homebound musicians to join monetization programs for their living-room livestreams on YouTube or Facebook, two other platforms — Stageit (founded by Evan Lowenstein, formerly of the twin powerpop duo Evan & Jaron) and video gaming site Twitch — may be the way of the future.

Early adopter Lowenstein, who came up with the idea for Stageit in 2011 when he realized that international touring wasn’t an efficient or economical way for him to promote his own solo music, says Stageit has generated more interest in the past few weeks than it has in years, with a “huge swell of artists that have never even tried Stageit before.” (As recently as March 13, Stageit hosted 27 shows day; less than a week later, that daily number was already at 240.) Some new Stageit headliners include Rhett Miller and the Indigo Girls, and this weekend, Stageit will kick off Digital DragFest, a 16-day virtual festival starring various RuPaul’s Drag Race alumni, Hedwig and the Angry Inch star John Cameron Mitchell, comedian Margaret Cho, and others.

Meanwhile, Twitch, which in the past few years has expanded from gaming to music and other creative arts, is broadcasting two big events this weekend: “36h INGRID,” a 36-hour music marathon hosted by Swedish indie-pop trio Peter Bjorn & John from the band’s INGRID Studios in Stockholm, and the all-star telethon “Stream Aid 2020,” featuring Ashley McBryde, Barry Gibb, Brandy Clark, Charlie Puth, Diplo, Ellie Goulding, John Legend, Michael McDonald, Marcus Mumford, Monsta X, Rita Ora, Ryan Tedder, Steve Aoki, and many more. Other regulars on Twitch include Panic! At the Disco’s Brendon Urie (who recently produced a song live on Twitch, and donates his Twitch earnings to charity), Frankie Grande, and Matt Heafy, the frontman for the metalcore band Trivium.

So, how exactly does this all work? Stageit has a fairly straightforward business model based on the real-life clubbing experience, with fans purchasing virtual tickets and ‘tips” for online concerts; Lowenstein chucklingly describes it as “like Facebook Live with a paywall and tip jar.” Twitch, on the other hand, operates under a “freemium model” — meaning it's free to use, but there are premium paid options like subscriber-only artist chats, song requests, and personal/customizable emojis (or “emotes”). Music and tech veteran Karen Allen, author of the handbook Twitch for Musicians, says Twitch’s latter feature is hugely popular with fans.

“The most common thing people want to do is they want to applaud, they want to dance, they want to laugh, they want to sing along,” Allen explains. “So, you can create an emoji that does that for them. There's lyrics in emoji, Zippo lighters for applause, and people really love using them. When you use the emoji in the chat, it shows people that you're a subscriber and band supporter — it’s like being in a fan club, kind of a badge of honor. You also get a little badge next to your username that says you're a subscriber, so that's a way to show how big of a fan you are. It's a way to directly support the streamer that's fun for the viewer to do.”

Still, with all free binge-worthy content online competing for viewers’ attention, can it really be expected that fans will be willing to pay good money to stream concerts? Lowenstein and Allen both say yes.

“When our [Stageit] platform went beta in March 2011, we had fans on average paying about $3.75 for a show. Today, that's over $16.50,” says Lowenstein. “Our biggest [monthly] revenue market ever [before the pandemic] was $274,000, but just last week, we did about $400,000.” Allen adds that she’s “seen up to 60 or 100 dollars” offered for a personal song request on Twitch.

“It's really about creating connections with people, and the validation they feel when you recognize them for contributing, and the validation that you feel as a streamer for someone participating in your stream,” says Allen. “Those are really powerful social dynamics, and when you have a strong social dynamic like that, when you feel you're getting something of value, it's a very natural human response to want to give something of value. And if you have options that meet them where they are, people will do it.

“Most people monetize on Facebook by throwing up, like, ‘Hey, this is my Venmo, here's my PayPal’ — which is honestly not very exciting, because it's not fun to give people money… Just handing over cash into the ether is not great,” Allen continues. “And this is where Twitch gets it right, and this is where YouTube [which has a similar monetization program] gets it right: They make it fun. It's fun just to give a cheer emote and see your name on the screen and see the little animation happen. That's cool. And to know that the artist actually is getting money from that? Awesome! I'm supporting you and I’m having fun? Done! Take my money! But if it's just ‘take my money,’ how is that fun for anybody? That's charity. Charity is hard. But spending money on entertainment is easy.”

Lowenstein likens the dynamic to an intimate street-busking scenario. “If you're walking down the street and pass someone playing saxophone on the corner, I don't think there's a real feeling you need to give that person any money. But if you stay there and watch them for 30 seconds, maybe five minutes, you start to feel like you should give this person a dollar. And the longer you stay, the more you [want to give], because then it’s a live experience. And so, Stageit creates that. When you're watching your favorite artist, you feel like you're taking something from them, and so you want to give in return.”

Both Lowenstein and Allen see the recent explosion of live-streamed concerts in the wake of the coronavirus crisis as a massive opportunity for artists looking to adapt in these economically uncertain times. But Lowenstein stresses that he doesn’t want to seem like he’s taking advantage of the situation. “Our pitch [to artists] is not to say, ‘Hey, we've been waiting for you! Don't ever go back to live touring! That's not what our agenda is at all,” he says. “We really felt that we didn't want this to be ‘our moment.’ … We're really trying to make this moment about the artist and what they're going through.” Interestingly, Lowenstein had already been investigating ways to expand Stageit last year, after environmentally conscious band Coldplay announced that they wanted to reduce their carbon footprint by limiting their touring. “We anticipated that there might be growth [in live-streaming], but we thought it was going to be something to do with global warming,” Lowenstein says.

Now Stageit is even more actively looking for ways to expand its operations to keep up with the new demand — including partnering with major brands to help underwrite the higher payouts that the company is now making to performers. “The majority of artists [used to] make about 63 percent, and we increased that to 80 percent, across the board. It's very challenging for us to do this, but we didn't want to wait around for some sort of lifeline at some point,” says Lowenstein. “It’s really just not very sustainable for us [to keep paying 80 percent], but it was more about, ‘Let's do this now, and figure out the rest later.’”

In the meantime, Stageit has teamed with digital media company Gunpowder & Sky, which is headed by former Viacom president Van Toffler, to launch “Stageit Local,” a concert series benefitting participating artists’ local restaurants, venues, and bars. And Twitch is expanding as well. “Everyone's looking at [live-stream partnerships] right now,” says Allen, noting that concert promoter AEG — which recently announced that it is postponing live tours for the time being — experimented with Twitch back in October 2019, by streaming two Red Rocks concerts by dubstep sensation Illenium. “I would argue that artists should be live-streaming anyway, because it's just a phenomenal way to build a fanbase and earn revenue,” Allen states.

That being said, while Lowenstein is all for larger artists doing live streams for charity, he’s concerned that superstars jumping onto Instagram Live (which is not monetizable) or doing other sorts of freebie online performances will make it difficult for smaller artists to convince fans to actually pay for live streams. “As an artist myself, I appreciate what [bigger] artists are doing, but I don't think they realize — and I don't want to call people out or single people out by name — that when a [big] artist gives away their time, and struggling artists are asking people for $5 to play, it is a challenge [for the smaller artist],” he says. “And so, that's why on our platform, we choose to not have any free shows. We don't want an artist up working hard and asking you for tips while you have [a larger artist] saying, ‘Hey, everyone can just watch for free, because I'm in the eyeball business, and at this point I’ve made so much money, I just want you to watch.’

“[Some bigger artists] are doing it sort of gimmicky, and I think they're undermining what the platform really can do for people,” Lowenstein elaborates. “There's a lot of [smaller] artists that need this consistently to pay their rent, but these [major acts] are just jumping in and having a good time, and I don't think they're mindful of the artists that, day in and day out, are looking to make a living.”

Still, Allen optimistically believes that mid-level and smaller artists have the chance to create an audience experience that larger artists simply cannot. “It’s a very, very different type of live-streaming. They're actually going to read the chat, and respond to people, and maybe take requests, and they're going to see every comment that goes up. John Legend and Keith Urban can't possibly keep up with the comments, there's no way; they probably have somebody helping them and pulling out the good ones. You don't get that sense that you're there with them, and they're not going to be on very long. But the [smaller] artists that really do [Twitch] live-streaming, they're up for at least two hours, like you're hanging out with them. They try to treat it like they’re having friends over to their house. They don't overproduce it. They’re not on a stage. The whole point of live-streaming is to break down those walls and create a connection with people, and if it looks and feels like glossy television, you can't create that connection. And fans are spending money on the experience of being with you. … People are almost there more for the community than they are for the content.”

Both Lowenstein and Allen stress that they don’t expect, or want, live-streaming to ever replace the traditional concert experience. “I don't want to sound old, but there's always been something about live music, that smell of a venue and meeting other people and bumping around,” says Lowenstein. But they agree that even when things get back to “normal,” whenever and whatever that might be, the music industry could actually be changed in some ways for the better.

“I think a lot of artists will be exposed to the power of live-streaming and will add it into their mix of things that they do — and they should,” says Allen. “I think every artist should be doing this, honestly. It's so incredibly powerful for building true engaged fanbases. And frankly, that's what we're here to do. We're not here to get YouTube views. We're not here to get Instagram followers. We're here to get fans. Fans are what sustain a career.”

For the latest news on the evolving coronavirus outbreak, follow along here. According to experts, people over 60 and those who are immunocompromised continue to be the most at risk. If you have questions, please reference the CDC and WHO’s resource guides.

Follow Lyndsey on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Amazon and Spotify.