Duncan Grant, review: life turned into one constant, mind-expanding work of art

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

You wait 43 years for a Duncan Grant exhibition, and then two come along at once. Not only that, but two peaches – with stories that not only complement, but augment the other.

The first, at Charleston – the Sussex farmhouse to which Grant (1885-1978) moved in 1916 with writer David Garnett and fellow painter Vanessa Bell, now a house museum – recreates the 1920 exhibition at Paterson-Carfax gallery, Mayfair, that first positioned Grant at the helm of the British avant garde. A few hundred metres from where Paterson-Carfax once stood, meanwhile, a similarly-sized show at Philip Mould explores how Charleston provided rich inspiration for Grant, and for Bell, both in that crucial moment and as the century advanced.

The germ of Duncan Grant: 1920 is a scrimpy list of painting titles, with dates and prices but no images. That means a small number of the original roster are not precisely identifiable, though in these cases curator Darren Clarke has supplemented with an alternative of the same date and theme.

Even with these stand-ins, the conceit is brilliant – a rip in time through which we can temporarily step, to witness British modernism strike out on its own. The Paterson-Carfax show was Grant’s first solo presentation, and thus the first time the public, then steeped in low-toned Edwardian painting, encountered his intense response to post impressionism. It must have been a bombshell: then as now, that movement’s heightened colours and broken brushwork ricochet through the three rooms.

It impresses most in Grant’s still lifes – two prismatic renderings of a coffee pot (1916 and 1919), for instance, and a glass cup (1916), which zing with energy. We understand immediately that he is experimenting with rendering surfaces, and with how to release colour from its descriptive function. A green whose depth shifts between eau de nil and teal seems a particular favourite.

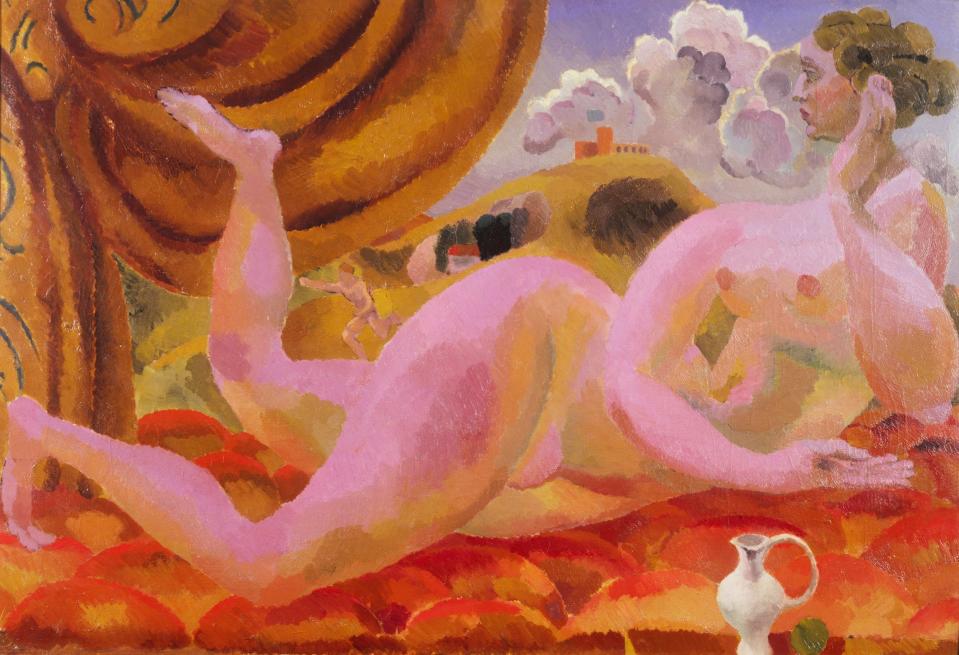

Grant’s experiments aren’t without duds. I didn’t much warm to Venus and Adonis (1919), whose contorted form accosts you at the entrance, its ill-weighted composition and boiled-pig hue a poor indication of the treasure to follow. Head instead for the beguiling Room with a View (also 1919), which pictures Bell on a deck chair through the open French windows of Charleston’s sitting room. Paintings of open windows were a great favourite of the post impressionists, particularly Matisse and Bonnard, because they were a means of doing away with the illusion of spatial depth (“The atmosphere of the landscape and my room are one and the same,” Matisse explained), but Grant has spun that precedent into something that is uniquely of his modest but magical environment.

Above Bell’s reclining form, puffs of pillowy blossom lean protectively, while the first shoots of spring burrow up from the earth. Sunlight skitters and pools, and even the shadows are alive with colour. “No one can look at his Room with a View without seeing that he is a born painter,” reads a contemporary newspaper review displayed nearby, “one whose very paint makes beauty.”

A work such as this, or a 1916 portrait of Garnett pouring over his books at the dining room table, or Grant’s various studies of identifiable objects in the house such as a wash-hand stand, underscore the degree to which this exhibition gains from its setting. Presented elsewhere, it could feel slight, but to study Grant’s paintings and then walk among the rooms and furniture and landscape that inspired them is really special – as is recognising a corner of the kitchen or a stairwell, for instance, if you see the Philip Mould show second, as I did.

Charleston: the Bloomsbury Muse covers the period 1912 to 1950, and splices Grant’s work with that of Bell. This serves to offer a much more rounded – and a more emphatic – sense of Charleston, as does the inclusion of several landscapes picturing the farmhouse’s outbuildings and the signature kinks and folds of the surrounding Sussex Downs. Look out for the two painted in the winter (one by Bell in 1940, the other by Grant in 1943) which possess an enchanting muffled stillness.

The exhibition benefits from the addition of objects – a wavy-lipped compotier, for example – that also appear in the paintings, or which, like the hand-decorated linen chest and pair of cupboard doors, convey the degree to which Grant, Bell and their unending stream of arty guests believed in the soul-warming, mind-expanding good to be had from turning everything they looked at, or lived amid, into a work of art. I loved, too, the sketchbook, snaps and short film of Grant at Charleston, which together evoke the strange wonder of this tiny, rural, overtly domestic setting becoming a crucible for fiercely experimental modern art.

'Duncan Grant: 1920', at Charleston, Sussex, until March 13. Tickets: 01323 811626; charleston.org.uk

'Charleston', at Philip Mould, London SW1, until Nov 10. Tickets: 020 7499 6818; philipmould.com