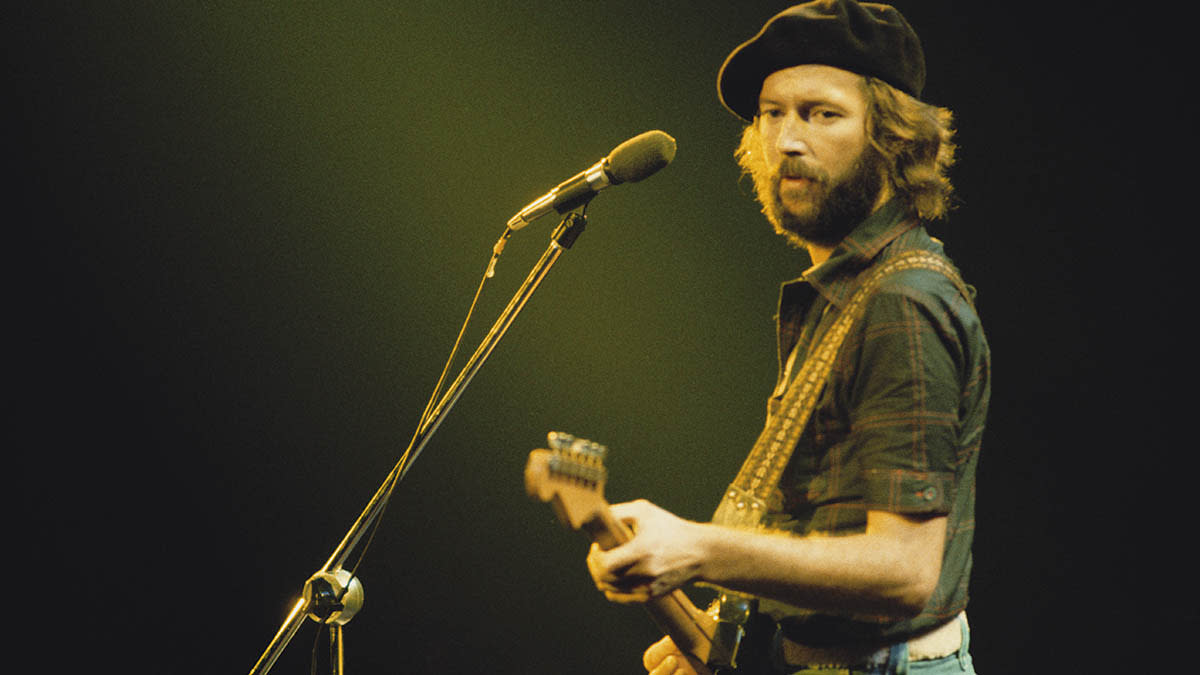

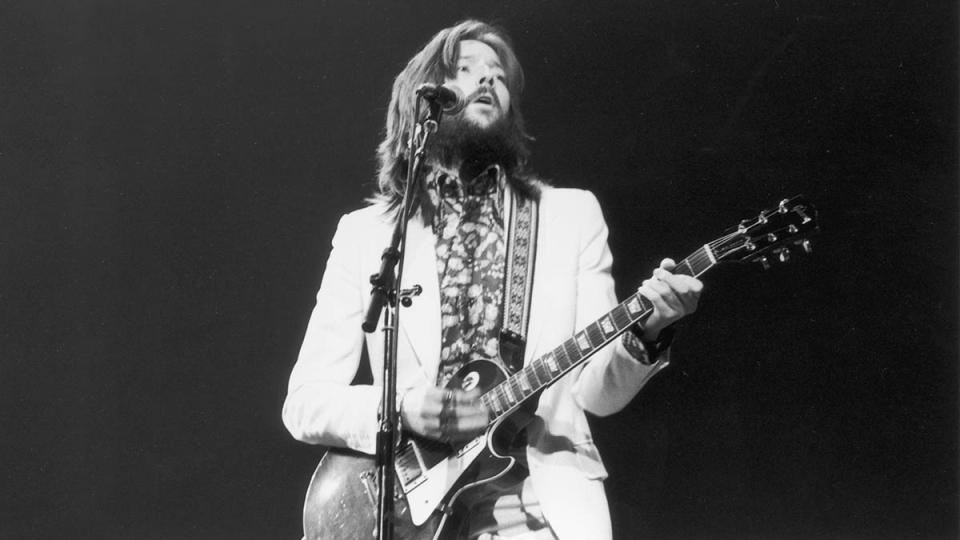

“Duane Allman played a great solo, came back, and Eric says, ‘Well, I want to do mine again!’ This went on for at least an hour or two”: How Eric Clapton went from God to all-'round guitar genius in the ‘70s

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

In late 1968, Eric Clapton and Steve Winwood had a conversation that would help define Clapton’s direction in the coming decade.

“We discussed the philosophy of what we wanted to do,” Clapton recalled in his autobiography. “Steve said that for him, it was all about unskilled labor, where you just played with your friends and fit the music around that. It was the opposite of virtuosity, and it rang a bell with me because I was trying so hard to escape the pseudo-virtuoso image I had helped create for myself.”

Indeed, Clapton’s Sixties hadn’t been so much swinging as swashbuckling. From the Yardbirds to the Bluesbreakers to Cream to Blind Faith, he leapt from band to band, wielding Teles, Les Pauls, SGs, and 335s, while fanatics with spray-paint cans started a new three-word graffiti gospel across England – “Clapton is God.”

In the final days of Cream, the by-then reluctant messiah’s go-to escape for sanity was the Band’s 1968 debut album, Music from Big Pink. That, and the music of J.J. Cale, with its understatement, groove, and economy, became stylistic templates for Clapton, as did a brief tour in 1969 with Delaney & Bonnie, who encouraged him to focus on his singing and songwriting.

So began the transition from ‘God’ to ‘good all-rounder.’

Of course, it wasn’t just musical influences that were shaping him. He came into the decade with a developing addiction to heroin, which – after his first solo album – became so debilitating that it sidelined him for two and a half years.

When he finally managed to get clean, it was only to trade one dependency for another. To read the chapters about the Seventies in Clapton’s autobiography is to almost feel contact drunkenness, so prevalent was his boozing. But like many alcoholics, he was high-functioning, and he continued to tour and make records.

What follows is a roundup of those records and key moments, along with conversations with a few supporting players who were integral to Clapton’s Seventies.

Eric Clapton (1970)

Opening songs say so much. Released in August 1970, Eric Clapton, his first solo album, could have rung in the new decade with the heralding guitar chime of Let It Rain, the big brass gallop of After Midnight, or the kicked-down doors of Leon Russell’s Blues Power.

Instead, he chose to slunk into the 11-song sequence with a funky instrumental jam called, well, Slunky. Led by Bobby Keys’ sax, it’s a minute-and-a-half before Clapton’s guitar appears, and even then, he’s mostly just idling on one note with wrist-shaking vibrato and repeating a six-note blues lick… So, what’s the message here?

It’s very much about subverting, then redefining, Clapton’s guitar hero status. As he put it to Circus, “Until I’m either a great songwriter or a great singer, I shall carry on being embarrassed when people come on with that praise stuff about my guitar solos.”

Until I’m either a great songwriter or a great singer, I shall carry on being embarrassed when people come on with that praise stuff about my guitar solos

To that end, this album really does make a steady move forward on those fronts. The lilting Easy Now, with its falsetto break melody and major-to-minor shifts, is an obvious nod to George Harrison (big strumming courtesy of “Ivan the Terrible,” Clapton’s beloved custom-made Tony Zemaitis 12-string guitar).

Bottle of Red Wine shuffles with searing, less-is-more blues licks. Lonesome and a Long Way from Home features one of Clapton’s most soulful, confident vocals. And even though he’d later complain that his voice sounded “too young” on this record, he strikes a balance between the grit and laid-back phrasing that would define his style.

Layla and Other Assorted Love Songs (1970)

Released just three months after his self-titled debut, Derek and the Dominos’ Layla and Other Assorted Love Songs marked the last of the five legendary bands that Clapton would join or lead before officially going solo.

With classics like the title track, Why Does Love Got to Be So Sad?, Bell Bottom Blues and his blazing cover of Freddie King’s Have You Ever Loved a Woman, the record was an exorcism for Clapton, working through his tortured love for Pattie Boyd, the wife of George Harrison. Because Clapton’s name and image was absent from the sleeve (the label later added stickers explaining that “Derek is Eric!”), the record initially didn’t sell.

Friendly Gunslinger: An interview with Chuck Kirkpatrick

Engineer Chuck Kirkpatrick – one of the last surviving members of the team behind Layla and Other Assorted Love Songs – spoke to us about his impressions of Clapton’s playing and his “friendly gunslinger” competition with Duane Allman.

What was your impression of Eric Clapton in 1970?

“From day one, he just wanted to play the blues, in a pure sense. He was trying to escape all that ‘Clapton is God’ stuff. He just wanted to be in a band. Because he was the most famous, he was the bandleader. But he didn’t dictate.”

How did Eric and Duane meet?

“We all went to see the Allman Brothers perform in Miami, and afterwards, Eric invited Duane back to Criteria Studios. At midnight, Duane walks in. Moments later, they were sitting down with guitars, laughing and trading licks.”

Were they competitive?

“Well, I remember the session for Why Does Love Got to Be So Sad? Duane and Eric came in to overdub solos. Eric went out, while Duane stayed in the control room, and he played a great solo. Then Tom Dowd said, ‘Now, Duane, you go out there and do one.’ So Duane played a great solo, came back, and Eric says, ‘Well, I want to do mine again!’ This went on for at least an hour or two. [Laughs] It was a gunfight, but a friendly one.”

He also used a blonde Fender Bandmaster for cleaner, fatter rhythm parts. But all the solos are played through the Champ, with no effects

What gear did Clapton use?

“His ‘Brownie’ Stratocaster into a Fender Champ. He would crank it all the way up, and that was the sound he liked. It was very easy to record because it really didn’t make all that much noise in the room. He also used a blonde Fender Bandmaster for cleaner, fatter rhythm parts. But all the solos are played through the Champ, with no effects.”

Did you have the sense during the making of this record that it was going to be as successful as it eventually became?

“When it came out, Atlantic either didn’t get behind it, or people were confused by the band name. The record didn’t take off until a few years later. What I thought then is what I still think – it’s one of the greatest guitar records ever made.”

1971 to 1973: I Looked Away

From 1971 to ’73, Clapton was in “self-imposed exile,” as he slipped deeper into heroin addiction. He admitted that, initially, he was swayed by the drug’s romantic mythology, surrounding the lives of musical heroes Charlie Parker and Ray Charles.

“But addiction doesn’t negotiate, and it gradually crept up on me, like a fog,” Clapton said. He half-heartedly tried clinics and therapies, but mostly spent his days “eating junk food, lying on the couch, and watching TV.”

His guitar skills atrophied. There were only two musical interludes during this period – George Harrison’s August 1971 Concert for Bangladesh in New York and a January 13, 1973, concert at London’s Rainbow Theatre, which was basically a rescue mission led by Steve Winwood and Pete Townshend “to prop Eric up and teach him how to play again.”

Addiction doesn’t negotiate, and it gradually crept up on me, like a fog

Finally, a stint on the family farm of his then-girlfriend, Alice Ormsby-Gore, helped Clapton “trade isolation for gregarious living” and rediscover the guitar and music. While he admitted that he traded one abusable substance for another, Clapton said he left the farm “fit, clean, and buzzing with excitement at the possibilities ahead.”

461 Ocean Boulevard (1974)

The title of 461 Ocean Boulevard represents the oceanside Miami address where Clapton started redefining himself musically. At Clapton’s request, Derek and the Dominos bassist Carl Radle had put together a core band, including Tulsa-based drummer Jamie Oldaker and pianist Dick Sims.

They were joined by local session guitarist George Terry, keyboardist Albhy Galuten and backing vocalist Yvonne Elliman (Mary Magdalene in Jesus Christ Superstar) at Criteria, with Tom Dowd in the producer’s chair.

For three weeks, working mostly through the wee hours, Clapton and the band jammed on blues covers by Robert Johnson and Willie Dixon and worked up three originals. There were a few extroverted moments, especially on Mainline Florida and Motherless Children, which retooled a 1927 gospel standard into a steamrolling romp. But mostly, the record sustains a slow-burn intensity – much influenced by J.J. Cale – especially on Give Me Strength, I Can’t Hold Out, and the gospel-esque Let It Grow.

The set’s surprise hit came via a cover of Bob Marley’s I Shot the Sheriff, which Clapton fought to leave off the record, but which helped make said record a Number 1 platinum-seller. Re-learning to play, his guitar solos are tasteful and simple throughout, more melodic than the “gymnastic playing” he’d come to resist. Clapton said, “I knew I could still play from the heart, and no matter how primitive or sloppy it sounded, it would be real. That was my strength.”

The Turning Point: An interview with Albhy Galuten

Best known for co-producing the Bee Gees’ Saturday Night Fever soundtrack, Albhy Galuten also worked with Diana Ross, Dolly Parton, and Jellyfish.

Starting as Tom Dowd’s assistant on the Derek and the Dominos record, Galuten joined Clapton’s studio band as keyboardist for 461 Ocean Boulevard, remaining part of the team for the rest of the decade. He also co-wrote Slowhand’s closing track, Peaches and Diesel, with Clapton.

Why was 461 Ocean Boulevard such an important album for Clapton?

“When Eric came back, he was clean, more relaxed and done with wanting to be famous. 461 was a turning point. He was leaving the bombast behind him. It was more like, ‘I just want to play with my friends in a band and make a nice record. We’re not going to worry about hits.’ He even said to me, ‘If I knew what hits were, then all blues records would be hits.’ Even though the album is laid-back, there’s an intensity to it, and that came out of his history of very emotional situations in his life.”

You’d worked with Clapton a few years earlier. How had his guitar playing changed?

“When he was younger, I think he was trying to impress people. Then as he got older, he was just trying to play the song. Eric put in his 10,000 hours to get his technique to where it was flawless. And then once he let it go, he was like Oscar Peterson or Ella Fitzgerald, where your instrument is second nature. He could play whatever he thought of.”

How did you come to write Peaches and Diesel with him?

“I had this little riff on a guitar and Eric liked it. He was very generous to develop it with me and give me a co-writing credit. But then, he’s always been that way. Years later, he’d make sure his producers got paid royalties from SoundExchange when most big artists never bothered.”

What do you think of those Seventies Clapton albums now?

“They stand up – for their realness and their humanity.”

And your lasting impression of Eric during that period?

“The main thing about Eric is he always loves playing. That’s his whole reason for being.”

E.C. Was Here (1975)

“C’mon, Eric, do some Cream!” yelled a disgruntled fan at a show in 1974. Such catcalls weren’t uncommon in the Seventies, and they got under Clapton’s skin.

Clapton admitted that his 1975 live album, E.C. Was Here, was a way of “filling that space that people were complaining about.” Of the six tracks, four are straight-ahead blues, and the other two from Blind Faith. Most top out over seven minutes long.

Robert Johnson’s Rambling On My Mind, more than any, proved that Clapton was still an inspired architect. For three-and-half minutes, over four separate key modulations, Clapton leans into Blackie with deep bends and a fiery abandon that recalls the Bluesbreakers’ “Beano” album from nine years earlier.

There’s One In Every Crowd (1975)

Clapton wanted to call 461’s sequel E.C. Is God: There’s One in Every Crowd, but his label failed to see the humor. Returning to Miami’s Criteria Studio with the same creative team and his road band well-tightened would have seemed to ensure success.

But despite a couple of memorable songs – the sinewy Singin’ the Blues and the buoyant, Allmans-like High, with Clapton and George Terry on tandem leads – the material doesn’t measure up. Both Swing Low Sweet Chariot and Don’t Blame Me try to replicate the reggae vibe of I Shot the Sheriff, while Opposites and Better Make It Through Today meander without quite arriving.

No Reason to Cry (1976)

Clapton told Crawdaddy in 1975, “I think I’ve explored the possibilities of that laid-back feel. The next studio album will be stronger, with stage numbers.”

And was it? Well, sort of. Upping stakes to the West Coast of the U.S.A., No Reason to Cry included a sprawling cast of contributors, including Bob Dylan, Ronnie Wood, Billy Preston, and the Band. But Clapton didn’t leave much room for himself, sounding more like a guest than the confident leader (his bandmates called him “Captain Clapton”) he was on the previous two albums.

On the Dylan-penned Sign Language, the two share lead vocals, though it sounds like neither claims the mic; meanwhile, the Band’s Robbie Robertson plays the (bizarre) guitar solo while his Band-mate, Rick Danko, sings lead on All Our Past Times. Newcomer vocalist Marcy Levy gets the most spotlight here, doing her best Linda Ronstadt on Innocent Times and Hungry. Overall, it’s an album that goes by pleasantly enough, but hardly invites repeated listens.

Slowhand (1977)

The front-loaded Slowhand is the purest distillation of everything Clapton was aiming for in the Seventies. His spirit guide, J.J. Cale, resides in the cover of Cocaine and the slippery country-blues groove of Lay Down Sally. And there’s the happy-ever-after sequel to Layla, the gentle Wonderful Tonight.

Apparently written in frustration while he was waiting for Pattie Boyd to get dressed for a party, Clapton delivers it in dewy tones, both vocally and with his Strat. As a contrast to the lean economy of Side 1, polished by new producer Glyn Johns, Clapton stretches out for The Core, an eight-minute response to all those frustrated fans who missed his extended solos.

The other highlight is John Martyn’s May You Never, which is one of Clapton’s warmest, most affecting vocals from any of his albums. Glyn Johns wrote in his autobiography, “It was like falling off a log working with this lot. Because they had been on the road for a few weeks, Eric and the band were in great form. There [was] a camaraderie between them socially as well as musically, Eric’s sense of humor was leading the way.”

Backless (1978)

“For most of the Seventies, I was content to lie back and do what I had to do with the least amount of effort,” Clapton said. “I was very grateful to be alive.” Clapton’s final studio album of the decade, Backless, brims with that feeling as it returns to the winning formula of Slowhand, with Glyn Johns producing 10 easy-to-like songs.

There’s a J.J. Cale cover (I’ll Make Love to You Anytime), a Marcy Levy duet (Roll It), a Lay Down Sally sequel (Watch Out for Lucy), two Dylan tunes and an eight-minute traditional blues that gives Clapton and George Terry room to stretch out on solos (Early in the Morning).

But it’s the final song that’s most memorable, a rocking tribute to the musical city that influenced so much of Clapton’s Seventies work – Tulsa Time.

When E.C. was Livin’ on Tulsa Time

In 1978, Nashville-based songwriter Danny Flowers was playing guitar on the road with country star Don Williams. The band had a night off in Tulsa. “It was the middle of blizzard, and I wrote Tulsa Time, in about 30 minutes in my hotel room while watching The Rockford Files – like you do,” Flowers says with a laugh. “I was thinking about my musician friends who lived there – Jamie Oldaker and Dick Sims, who played with Eric – and the vibe of the place.”

The next day, at a rehearsal, the band started working up Flowers’ new song. Williams heard it and loved it. Flowers says, “He said, ‘Get me the lyric, I want to record it.’” A week later, they were opening a concert for Clapton in Nashville. Flowers says, “Eric used to come to our shows and was a big fan of Don’s.” Afterwards, Flowers was hanging out with Williams in Clapton’s hotel room.

“We were playing guitars, and Don says, ‘Danny, play that new song.’ So I’m doing it, and Don’s playing rhythm and Eric’s playing Dobro. I thought I’d died and gone to heaven. When I got through, Eric said, ‘I love that song and I want to record it right away.’ Don said, ‘No, you can’t record it. It’s mine!’ They were play-arguing. I said, ‘If you’re gonna fight, I’m not gonna let either one of you have it.’”

A few months later, Flowers bought a copy of Backless. “And there it was, my name on the back of a Clapton album,” he says. “It was a beautiful thing.”

Knowing that much of Clapton’s music in the Seventies felt like a tribute to Tulsa’s J.J. Cale, Flowers says, “One of the biggest compliments I ever got about Tulsa Time was somebody who knew J.J. asked him if he had written that song, and he said, ‘No, but I wish I had!’”