Dry Wall and a Broken Jaw: Modest Mouse Reflect on The Moon & Antarctica 20 Years Later

In our oral history, band’s Isaac Brock and Jeremiah Green, producer Brian Deck, Califone’s Tim Rutili and violinist Tyler Reilly reflect on indie-rock group’s leap forward.

Everything about Modest Mouse’s third LP, The Moon & Antarctica, was more expansive: the guitar sound, the production, the lyrical imagery, the budget and — crucially — the expectations. The Washington trio expanded their cult following on 1997’s The Lonesome Crowded West, leading to one of rock’s classic cliché narratives: the pivot to a major label. But after signing with Sony’s Epic Records, the group only grew more ambitious in the recording studio, partnering with producer Brian Deck (Califone, Red Red Meat) for the most grandiose, densely layered album in their catalog.

Click here to read the full article on SPIN.

More from SPIN:

With indie-rock culture creeping further into the mainstream at the end of the decade, and with a bigger promotional engine carrying the band forward, Modest Mouse were poised for some kind of commercial breakthrough — one that ultimately arrived with their polished 2004 hit “Float On.” They deny feeling the weight of expectation during the Moon sessions; still, their subsequent success — headlining festival slots, Grammy nods, collaborations with rock icons like The Smiths’ Johnny Marr — would have been unlikely had the album flopped.

Singer-guitarist Isaac Brock, drummer Jeremiah Green and bassist Eric Judy (who left the lineup in 2012) tracked The Moon & Antarctica from July to November 1999 at Deck’s newly assembled Clava Studios in Chicago. There, they utilized a massive crew of contributors — including violinist Tyler Reilly, percussionist Ben Massarella (now a full-time member), multi-instrumentalist Ben Blankenship and Califone/Red Red Meat member Tim Rutili — to bring these 15 songs to life.

To mark the record’s 20th anniversary, we spoke to Brock, Green, Deck, Reilly and Rutili about the sonic experimentation (mountains of guitar overdubs), turmoil (Brock getting his jaw broken by a blindsiding punch in a local park) and studio bliss (the basic track used on “The Stars Are Projectors”) that defined the sessions.

Moonrise: Before the Sessions

Tim Rutili: The first show [Red Red Meat] played with Modest Mouse was in Seattle, probably 1996. They looked like little kids. They alternated between being a total mess and [turning] on a dime and playing an incredible song. You could feel the air in the room change. That happened a few times during their set that night — they’d go from shitty mess into unintelligible stage banter into a great song that elevated the energy in the room. I remember Isaac talking to me after the show. He told me what he really liked about Red Red Meat and what he didn’t like about our band and our records. I thought he was a mentally handicapped teenager.

Isaac Brock: I played with [Red Red Meat] during a song or two for a show. We used to tour a lot with Califone [which featured Deck and Rutili, along with future Modest Mouse member Ben Massarella], so we just spend a lot of time taking turns in each other’s bands. That was great.

Rutili: I did not keep in touch with [Modest Mouse]. I liked their first few records and a lot of what was being released on Up Records at the time. We got invited to tour with them through our booking agents. We got to know them really well on those tours. First thing I noticed — Isaac wasn’t mentally handicapped at all. He was a highly intelligent, brutally funny, sweet young man and also kind of a chaotic maniac. Eric and Jeremiah were great musicians and also very sweet, funny people. The songs kept getting better and better. Sometimes the chaos would take over the show, but I remember some incredible nights.

After those tours, Isaac came to Chicago. He worked at Ben’s truck stop with us, washing out the blood out of meat trucks, and he played music with us for a summer. We played a Red Red Meat show at The Empty Bottle [an indie-rock venue in the Ukrainian Village neighborhood of Chicago], and Isaac played guitar on the entire set with us. He also played with us at a bunch of Califone rehearsals. maybe even a show or two.

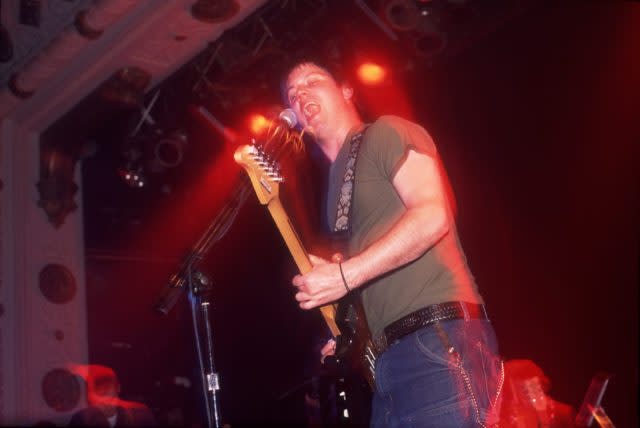

Credit: Paul Natkin/Getty Images

That connection proved crucial when Modest Mouse invited Deck to produce their third album.

Brian Deck: [Brock] really admired Red Red Meat and Califone. I had been doing most of the production for a good while. Tim and Ben had started a record label called Perishable, and Ben and I started a recording studio called Clava, and I was recording most of the music for the label at the time. That’s one of the reasons I stayed home when [Modest Mouse and Califone] went on tour. I guess the guys in Modest Mouse asked, “Where’s Brian? We thought he’d be out too.” I think it was Tim who put Isaac and me back in touch and said, “Hey, here’s his phone number. Call him.” Modest Mouse was thinking about signing with a major label. We spent a lot of time talking about what was good about that, what wasn’t so good about that.

Brock: I kinda didn’t give a shit [about the shift from independent to major]. I wasn’t that nervous about it. My mind wasn’t too heavy on the fact that it was a change, that there should be a different approach. I do remember one thing that affected my thinking: I really didn’t want to come out of the gate alienating everyone. Now I look at it and am like, “Why the fuck should anyone care?” But it was important to people that, if you’re no longer an independent band, [you don’t] start making easy crap [and do] a pop version of yourself. I wouldn’t say I was self-conscious, but I was aware that I didn’t want it to sound like we were pandering to radio or something.

The material they were gathering certainly didn’t signal a pivot toward commercialism. But the label was invested in their new signees, sending them to record a batch of demos for songs that wound up on The Moon & Antarctica. [Those early versions, recorded by veteran producer Phil Ek — who let the band practice in his basement — comprised the limited-release 1999 EP Night on the Sun.] Then roughly two months before they started work on the album, Deck accompanied the band to Seattle for some pre-production rehearsals, where some of the songs started to solidify.

Deck: I remember we’d poured concrete to even out the floor a couple days before I went to Seattle. I literally drew the floor plan on a napkin for the guys to start construction in my absence. [laughs] It was pretty seat-of-the-pants. I tried to explain how things should go, and then I got on a plane. I was on the phone all the time, trying to direct things. I’m remembering now how much anxiety I had about building a studio around the same time I was doing pre-production. It was my very first major-label experience.

I remember some things about those rehearsals. We would have barbecues at night and sit out and talk about the record. I will tell you this: If the [expansive, layered sound] of The Moon and Antarctica fulfilled a clear vision that Isaac had in the beginning, I was not [fully] aware of that vision.

The record’s spacey, dense sound gradually evolved at the Clava studio, their home base for the sessions.

Deck: We built the permanent Clava recording studio adjacent to the Perishable offices in the Bridgeport neighborhood in Chicago. The Modest Mouse record was the first thing we recorded there. They were so excited to start recording that they started driving early. A couple weeks before I expected them, they showed up — and helped us hang drywall.

Brock: My friend who’d driven out with me helped hang drywall. I’d like to say I helped, but I sat at a desk.

Deck: It was embarrassing and terrifying to have my first major-label band show up and not have the recording studio finished being built. It’s a pretty complex thing. Typically you test shit out before your first client shows up. Rather than get the chance to test it out, they finished building it.

Full Moon: The Sessions

Jeremiah Green: [Eric] and I drove out to Chicago together to do our part of that recording. We had this apartment above the studio. There were three rooms: Isaac and his girlfriend were in one; Eric and I in one; this dude Ben Blankenship [in another].

Brock: He was this dude from around town who claimed to know how to play a lot more things than he did. Or maybe he just didn’t know how to incorporate them into what we were doing. The band was a little free-form as far as people coming and going. It wasn’t something we really thought about much, like, “We’re adding a new band member!” and chiseling their name on the fucking foundation in stone.

Green: Ben would get extra creative, to the point where people would be like, “What are you doing? You’re wasting our time.” But the end result would be this cool thing. I remember [on “Paper Thin Walls”], he tuned up like five guitars to different chords so he could play this part on each guitar. It’s just this simple part that happened twice. These days, we have more of a budget and time to do stuff like that. But at the time, it was like, “We’re gonna take three hours to record this one part of the song?” It seemed wacky. But it was cool.

Brock: He’d just walk by and play each note, and it would ring out. That’s the one thing I remember him doing that I thought was great.

Credit: Paul Natkin/Getty Images

The band wrapped basic instrumental tracking after roughly three weeks. But the sessions were temporarily derailed when Brock was punched in the face in a local park, breaking his jaw. That incident — which seems to have inspired the ragged, unreleased song “Jawbreaker,” played live once in 2001 — also marked a pivotal creative shift.

Deck: It was a real changing point. It was the first day of recording real vocals. I went home, and Isaac and a couple other people went to The Empty Bottle. They came home late to the apartment and parked his van next to the city park across the corner. It was very late at night, and he struck up a conversation with some people. Someone punched him in the jaw and broke his jaw. He was certainly not picking a fight. I believe he was actually trying to do the opposite — just chill them out and say hi.

Brock: Territorial pissings, man. Bigger cities are almost like rural communities in their own ways — your neighborhood is your fucking neighborhood. The local kids were very possessive of their spot. Outsiders were pummeled. I wasn’t the only guy who got his ass kicked in that park. They didn’t want a bunch of fuckin’ weirdos in their neighborhood. I didn’t read the room right. I showed up from drinking, and I walked over and was gonna say hi. I got as far as saying, “Hey, how are y’all doing?”, and out of the corner of my eye, I saw [something] hit my head like a big golf ball on a tee.

It was one of the few times [I experienced] that thing people talk about where time literally slows down. They were throwing bottles. There were like 15 of them coming in my direction. I remember I would move my head to the left or right and a bottle would slo-mo by. It was a really good punch; my hat’s off to the fella. That neighborhood has one of the leading Golden Glove boxing establishments. Those kids know how to hit someone. My mind hadn’t kicked into, “Also they might just kill me.” But I knew I didn’t want any more of what I just got. [They yelled] “Fuck you, cowboy!” I remember being like, “Cowboy?” I looked down and was like, “I’m wearing a Western shirt. I guess not everyone wears Western shirts.”

Deck: I didn’t find out until the next morning that he went to the hospital and had surgery and they wired his jaw shut. I believe his jaw stayed wired shut for six weeks.

Deck: I made him rough mixes onto a cassette tape, and he listened and listened in the hospital. I think that’s when he decided it wasn’t done. I don’t know if it didn’t fulfill a vision he had or if he had a greater vision for what it could be. The record we’d made up until that point was more production-y than their previous records — there were more layers already. But there was nothing near the amount of guitars and vocals that ended up on the finished product. When his jaw was still wired shut but his energy had returned and he felt OK again, he said, “I think we’re not finished with this instrumentally. I’d like to get back in there and keep recording.” I remember him telling me this in the kitchen of my apartment. I said, “Are you sure? Wow. I thought we worked really hard on that and nailed it.” He said, “I think there could be a lot more.” That’s when we started to turn it into the record that it is.

Rutili: I think having all that extra time waiting for his jaw to heal made the record better.

Brock doesn’t recall having a creative epiphany in the hospital. Instead, the album’s guitar-heavy sound developed from a more practical place.

Brock: I felt like it needed a lot of work. Once I got my mouth wired shut, singing kinda wasn’t an option. I was stuck inside — the folks who broke my jaw were looking for another shot at it. I wasn’t able to work on vocals, so I spent a lot of time just adding shit.

Deck: I may have expressed a little skepticism at the beginning. I can tell you one anecdotal story that makes me think that: We had been trying to get “The Stars Are Projectors” for most of a day during those first three weeks. The band just wasn’t feeling it for whatever reason. I remember someone saying, “It’s too early in the day to play a song like this.” I remember someone saying, “It’s hard to play a song like this when you’ve played it so many times in a row.”

I seem to remember it was like 8 p.m. I said, “Let’s turn the lights down, adjust our attitudes and try this thing one more time. If we don’t get it, we’ll just call it a night.” We did that, and they did the performance that’s on the record. My jaw was on the floor. It was just fucking amazing. They nailed it. I thought to myself — as it was happening, and again, as we listened back in the control room — that it really encapsulates the entire production. Whatever this song could become, it doesn’t need any accoutrements, any ornamentation. Even the scratch vocal, I thought, could be the final vocal.

Brock: I remember that when we got it, it didn’t require any editing. We just fucking did it.

The album wouldn’t have sounded so vast without its expanded cast: Massarella contributed some experimental percussion; Rutili added a memorable backing vocal to “Paper Thin Walls.” Reilly, primarily a classical player who previously performed on “Jesus Christ Was an Only Child” from The Lonesome Crowded West, lifted many of the tracks with his ghostly string parts; a key contribution appears on the spacey, simmering “The Cold Part.”

Reilly: With [“The Cold Part”], I had to tune down my low G string to be in tune with his guitar. It sounds really hollow and cold. It took a while to get it in tune and get the changes right. I don’t know if Isaac didn’t tune his guitar or if he meant to be a whole step low or what, but it turned out to make the sound that the song needed.

Green: It’s hard to tell if a lot of those sounds are guitars or percussion because they’re dubbed-out and affected with delay and feedback. We used to use a vibrator on a lot of things [including “The Cold Part”]. He’d use it on anything: a bedpan, a floor tom, a cymbal.

In early October 1999, one month before finishing the sessions, Modest Mouse performed at the first Coachella festival in Indio, California. It was, let’s say, a memorable gig.

Brock: I pulled [the wires out of my mouth] myself. I’d already done like four shows on that tour with my mouth wired shut, singing like this [does garbled vocal impression], and I just didn’t want to play another one. [The wires] were all twisted up, and there was a shit-ton of blood. I eventually realized that I’d fucked up the enamel on my teeth in those areas. There were a fair number of root canals that followed that.

I was in so much pain when we did Coachella. Just like when you get a cast-off, your muscles have kinda atrophied in the jaw. It was weak and still hurt. So I ate a bunch of painkillers that I’d had from the doctor, and I don’t think we played one single song even close to right. It was just a blurry fucking mess. Then I think Spiritualized played afterward, and that had to have been real nice for everyone.

Moonset: The Album’s Release and Legacy

Modest Mouse finished tracking The Moon & Antarctica in November 1999, wrapping a five-month process. They released the album on June 13th, 2000 — earning breathless reviews across the board (though, ironically, a mixed assessment from SPIN). Everyone else noticed the artistic leap — including the album’s cohesive, cinematic quality — even if the band members themselves were too deep in the weeds to notice at the time.)

Green: But there were all these other bands like the Strokes and whatnot who just blew up. I remember going to England and them being on the cover of The Face and being kinda jealous, like, “They only got two songs out, man!” I went to the record store and bought their single, like, “I gotta hear this shit. They’ve got two songs on a CD single for $6. Who are these fucking posers?” [laughs] I was kinda jealous and pissed about it. I like the Strokes now, but at that time indie-rock stuff was getting really popular, and we didn’t really blow up like that. I expected a little more — that Sony would make us more popular. I was a little bit, like, “Why did we sign to a major label?” It worked out by the time “Float On” and all that shit happened. The record did good, but still…

I don’t think anybody knows if they’ve made their best records. I just felt like we made another album. I can’t say I felt like it was our best album. Sonically I was excited about it because it had a lot more cool shit.

Reilly: There are so few albums where you just want to start it at the beginning, turn the lights off and listen to the whole thing. That album is really special. The real essence of [Brock’s] songwriting was captured on The Lonesome Crowded West and The Moon & Antarctica.

Rutili: Eric, Jeremiah and Isaac had a weird, beautiful chemistry that seemed to totally coalesce around that time. Brian brought some beautiful focus and texture to the sound of the band that had never been there before. Brian elevated the whole thing. But — he’d be the first to tell you — you can’t elevate a turd. The songs and band have to bring in something special.

Brock: You always hope for the best for any record. That was probably the first [Modest Mouse album] record that kinda nailed that, where we actually got it feeling as big as we wanted.

To see our running list of the top 100 greatest guitarists of all time, click here.