‘Doubt’ Broadway review: Nun play still scorches — even in a so-so revival

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

It’s hard to believe it’s been 20 years since the off-Broadway premiere of “Doubt,” John Patrick Shanley’s scorching drama about a nun who suspects the parish pastor of being a child molester.

Theater review

DOUBT

90 minutes with no intermission. At the Todd Haimes Theatre, 227 W. 42nd Street.

Not because time has flown. It hasn’t, as is evidenced by how starkly different some scenes play two decades — and several earth-shaking social movements — later.

That disbelief comes from the realization that after only 20 years, “Doubt” has returned to Broadway as a bona fide classic. It’s as weighty and confident as American plays four times its age — not to mention leagues better than most of the new crop.

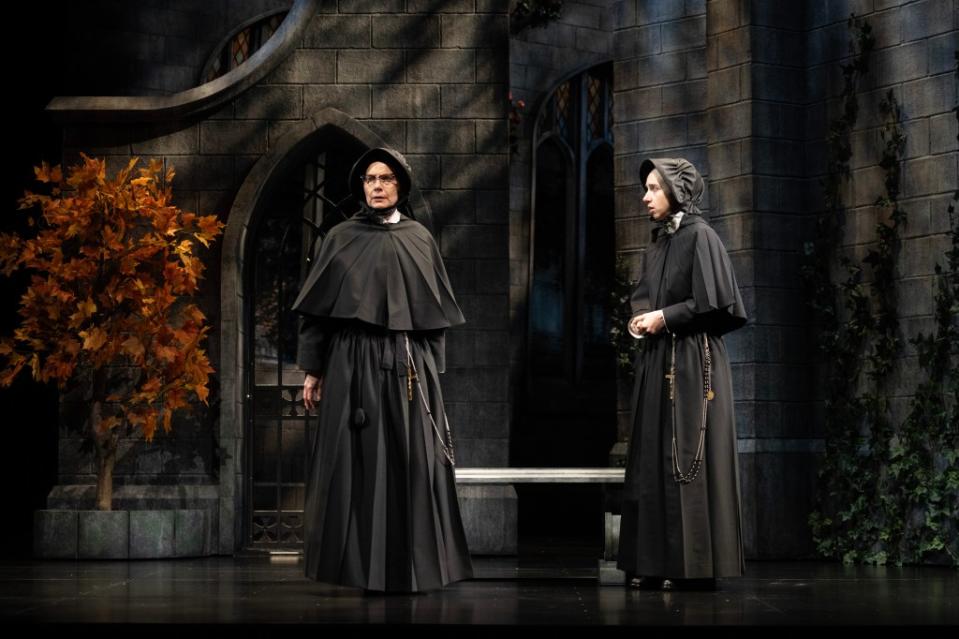

Shanley wrote an immaculate work that can stand up to even so-so productions like the revival starring Amy Ryan and Liev Schreiber that opened Thursday at the Todd Haimes Theatre.

The script is the marquee star. And although the head-to-head battles between Sister Aloysius (Ryan) and Father Flynn (Schreiber) don’t explode as powerfully here as they are capable of doing, the words are never less than riveting.

Determined as ever is Sister Aloysius, a Bronx grade school principal who is dead certain that the popular new priest is having inappropriate relations with a black altar boy named Donald Muller.

So, she recruits the beaming, positive, young Sister James — her total opposite — to help force a confession from the pastor.

Those twenty years, it would seem, have changed how audiences view the heroically resolute Aloysius.

“Doubt” debuted not long after a Boston Globe investigation revealed widespread child abuse in the Catholic Church, and ticket-buyers at the time were inclined to side with the dogged sister, despite her reliance on intuition over concrete proof.

With some distance from those terrible headlines, viewers appear less sure whose camp they’re in.

As Ryan’s Aloysius clashed with Flynn in her office, I had never felt a theater be so sympathetic toward the accused priest. I even saw supportive finger snaps at his self-defense.

That response could be because Schreiber exudes such a warm, paternal energy that never feels sinister or remotely creepy. He acts rationally and makes a reasonable case for his innocence. You couldn’t say that about Philip Seymour Hoffman’s performance in the 2008 film co-starring Meryl Streep.

Or perhaps the shifting sands are due to Ryan’s take. Aloysius is never likable, per se. She’s admirable — a defiantly old-world Catholic who resists the modern changes the church was making in the mid-1960s.

But Ryan plays her with a “danger Will Robinson!” roboticism that cools down the icicle even more. This is, after all, a woman who casually tosses off lines like “Innocence is a form of laziness.” Ryan is more pesky than ferocious, more another-day-in-the-rectory than larger-than-life.

Both are valid choices. Both are strong performances. That the play, which never tells you the full truth, has grown more ambiguous is fascinating. However, the pair of actors just do not click.

Quincy Tyler Bernstine makes a moving Mrs. Muller, whose speech about her son’s future still hits hard. And Zoe Kazan has the right wide-eyed optimism for James. Unlike Aloysius, whose husband died in World War II, she has not yet experienced the world’s cruelty.

But director Scott Ellis’ production has a bothersome tendency to ride the brakes. Every time the drama is about to really pack a punch, it stops and slows down. Shanley’s thunderous climax drizzles.

Still, you could do worse than attend a merely adequate production of one of the best plays of the millennium.