DOPEY: THE TRIUMPH AND TRAGEDY OF THE WORLD’S GREATEST PODCAST

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Now folks look at me like I’m destined to lose,

With my track marks and Jesus Christ tattoos

But I’m too tired to tell them to walk in my shoes

So I’m going where a man is never refusedMatt Butler

More from Spin:

It was the worst of podcasts. It was the best of podcasts.

One of the things that pissed me off in the early days of Dopey (tagline: “a podcast about drugs, addiction, and dumb shit”), seven years ago when the audience was just me and a small disarray of misfits, was the audio quality. Hosts and guests alike drifted away from the mic to vape or rang in on phones that sounded keistered. Thinking about it still shits me.

Because early Dopey fucked my neck.

I’d download episodes for a regular three-hour intercity commute, driving in my aging car with a portable Bluetooth speaker wedged under the seat belt where it crossed my shoulder, head tilted sharply to mash my ear against it so I could hear the show over road noise.

Try holding that position for three hours straight a few times a week and see how your neck likes it.

Couple of oxys might have helped, I suppose.

Anyway, the other thing that irked me were the interminable cross-interruptions and bickering of the East Coast junkie-bro hosting duo, Chris O’Connor and Dave Manheim.

So not only was the show physically injurious (FYI, I wound up seeing a physiotherapist instead of quaffing opiates), but all the waffle, tangents, and snarkiness between this odd couple who had met in rehab was aggravating. When Dopey was recorded in Dave’s father’s Manhattan apartment, the father himself would sometimes wander in to critique the show and its standards, and I tell you he was right.

Except, that is, for those golden moments when Dopey finally, finally delivered its high.

The euphoria came when they triangulated with piercing insight our complex, fallen, self-sabotaging, grace-seeking natures, as well as when the show became wildly, appallingly funny — like a chemically suicidal Jackass — via the gallows humor and depraved determination of the “war stories” of junkiedom told by the hosts and guests. Humans will climb any mountain — and get maimed and killed in the process — to avoid walking a straight line.

Dave spoke of a junkie superpower, a supersonic hustle that draws on an inexhaustible capacity for lying and manipulation in order to find a way no matter what to get what you want: which was heroin — dope — for Dave for many years, and for Chris it was almost anything that got him obliterated or wired tight.

Dave talked of using his junkie superpower in his post-dopefiend life to get into paid events without paying, to promote the deli where he worked, and to get celebrity guests for Dopey. He’d keep the audience informed of his hustles and stalkery badgering of people like comedian Artie Lange, and of how his wife was wise to his shifty abilities and if she smelt a ruse she’d tell him: “stop dope-fiending me.”

When Dopey started in January of 2016, Dave was a 41-year-old Jewish deli waiter from New York City who in his 20s had hosted a college-music cable show on the Burly Bear Network but had then slid into the embrace of heroin and stayed there for around 15 years – until just four months before the podcast started. While Chris’ stories were those of a true maniac of intoxication, a man who’d chased total derangement of the senses, Dave’s were more of a man given to a pervasive anxiety that heroin promised to relieve.

A longtime fan of Howard Stern and his needling ways, Dave would prod and tease Chris. He never missed a chance, for example, to throw “SMI” at Chris, meaning Serious Mental Illness, a label Chris had once earned by faking crazy in a facility (going berserk and smashing shit, before rocking back and forth in a chair in front of a counselor while repeatedly mumbling: “I don’t know, man”) so that he could get a buzz from antipsychotic meds.

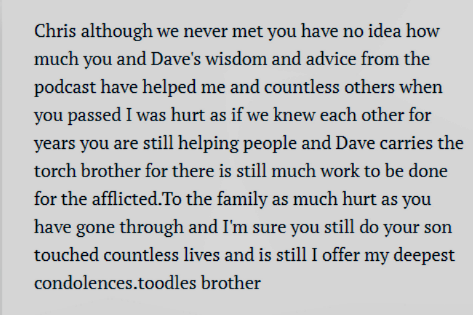

In the 2016 launch, Chris was 31 and sober for almost two years. He was the prodigal son of a wealthy Boston family, laid back and full of easy charm, highly educated with a Masters degree and soon to start a doctorate in psychology, and able to describe with humor and in lurid detail his past as a gratuitous drug pig and abject drunkard.

Chris, who’d started getting wasted even before adolescence, talked us through shooting meth as a court-ordered resident of a brain injury clinic; breaking his neck in a drunken skiing accident; loading a syringe with water puddled in a garbage can; tomfoolery during the rehab stints he’d done all over the country; and a year’s stretch he served in jail after fronting up to a Newport Beach, CA, veterinary clinic and demanding phenobarbital. His ruse about a cat having seizures didn’t work, so he knocked down a nurse and stormed the med room for a bottle of pills, before hot-footing it to a park where he attacked the arriving police.

Chris and Dave only became friends while doing the show, not before, and so listening to Dopey meant listening — in nakedly unproduced weekly installments — to an expanding warmth and familiarity between two smart and interesting men who had wasted much of their lives, betrayed and caused untold agony to those who most loved them, and were now belatedly acting with responsibility and purpose.

The ups and downs of their contemporary off-mic lives and loves were fodder for discussion, so listening to Dopey also meant weekly accounts of work and of relationships developing or healing after all the damage that junkie scumbaggery inflicts, and, in Dave’s case, of parenting.

Whether we are addicts or not, for those of us whose pursuit of roads less traveled has left us less secure in many ways than our more life-by-the-numbers peers, these guys were warm, thought-provoking, and optimistic company.

Other dopefiends and alcoholics, more of the endless ranks of the afflicted, appeared on the show, some becoming regulars giving updates on struggling to stay clean, or how they finally made it to an unemployment benefit appointment, but high on smack only to then nod off during the required interview.

There are callers like Andrew Cohen, a self-described hobo and addict who is just so lost. It just can’t help but tug at the heartstrings when he rings from the latest byway of his heartful misadventure.

Or Dave’s best friend, Todd Cury, an old college buddy that introduced Dave to the woman who became his wife, and with whom he became a parent. Todd is slated to take a third hosting-mic when he cleans up, but, you know, maybe he’ll kick tomorrow. Dave and Todd got into heroin together, and, while Dave got out before starting Dopey, Todd’s still there. And while Dave is now exercising control over his life and taking on ever greater responsibilities, Todd remains controlled by a need for junk. He often lives with his parents, whom he talks about, as he does the logistical challenges he faces as a junkie.

Dave tells him if he gets six months clean he can be the third host.

These are charming and self-deprecating people, even if arrested in their development by forever orbiting an endless need.

And then, late in 2017, Andrew stops calling in. He’s dead, Dave says. Overdosed at 26.

Andrew’s heartbroken mother later calls in place of her son.

I’d become attached to Andrew and his nomadic heart. For me, as a listener, it’s like a favorite character being killed off in a show, but it’s not — because it’s real. It’s mesmerizingly, agonizingly real.

And then in June the next year, Dave announces that his best friend and recurring guest, Todd, is dead. At the age of 44, Todd overdosed on fentanyl at his parent’s home.

And I’d become attached to Todd.

He bumbled about like a perpetual slacker, and was obviously a long term slave to smack, but he could be both chained in that slavery, and distant enough from it in some sense — in some free whisp of his soul — to observe it in all its tragic absurdity. And then it killed him.

In talking about Todd’s death, Dave says to us: “If you’re out there and you think you’re going to get away with it, you might not. You know what I mean? And, like, you guys should really fucking know that it could all end.”

Over the next few episodes, Chris grows short-tempered and bored-sounding, and then Dave comes on and says: “The worst thing that could ever have happened has happened. Chris relapsed and died.”

I am stunned.

Shaken to the core.

Chris’ shell-shocked partner, Annie, then comes on Dopey to describe in gut-wrenching detail finding Chris’ corpse in their bedroom, as well as sharing the increasingly alarming events leading up to his fentanyl overdose, and the aftermath.

Quite a show, huh.

Absolutely fucking raw.

I don’t think Dave will keep going, but he does.

I need a break, though. It’s too distressing. Too bizarre.

When I ease back in, I find Dave has remained his idiosyncratic self but grown into a highly accomplished interviewer who, in the pursuit of eliciting an honest portrait of life, peels the veneers from his interviewees with grace, respect, and self-deprecation.

But the next year, I get put off again when Ira Glass’ This American Life radio show and podcast neatly packages the Dopey story.

And that kind of exposure immediately swells the Dopey audience with people who weren’t there from the start, who didn’t fuck their necks straining to listen in those early amateur years, and — most of all — who did not live through the hammer blows of shock and grief.

Bunch of fucking Johnny-come-latelies.

Anyway, I have to learn to let go.

Dopey is now closing in on 10 million downloads of its more than 400 episodes, and has live events (Dopeycon), a fervent international following (the Dopey Nation) with a proliferation of online sobriety and support communities and meetings.

The archives keep growing, with Dave now having conducted penetrating interviews with hundreds of afflicted guests, ranging from the high profile (such as Darryl “DMC” McDaniels from Run DMC, Steve Earle, Brandon Novak from Jackass, Colin Hay from Men at Work, Steven Adler from Guns N Roses, comic and author Amy Dresner, actors Tom Arnold and Danny Trejo, Steve Gorman from the Black Crowes) to the same kinds of struggling “nobodies” who have always called in to share what’s happening in their lives.

Recently Dave’s been talking regularly to “Fentanyl Jay” as this reckless guy in his late 20’s winds his way towards starting a prison sentence for dealing. It’s sad, funny, tragic, informative, compelling, and opens the heart. That’s Dopey.

And this summer brings the fifth anniversaries of Todd’s and Chris’ deaths, so it seemed as good a time as any to talk to the great survivor and thriver, Dave Manheim.

SPIN: It’s been a hard experience living through your podcast. The friendships on it were vivid, tangible: I could feel them in the air. Your friend Todd had so much charm, and then bang, these people don’t exist anymore. But I guess that’s the addict’s life, right? People are just gone all of a sudden.

DAVE MANHEIM: It’s funny you should say that because I was in active addiction for 15 years, shooting heroin on a daily basis, and nobody I knew died. It wasn’t until we started doing the show that people I knew started dying. But that was before fentanyl.

Todd never stopped using, and his death should have been the most obvious for me to see coming, but it was very painful. I don’t do many interviews, and I don’t talk to many people outside of my fold, so to hear you mention it — it hits me because he is my friend, my very close friend, and it’s on the show. You listen to the show, and you can ask me that question, but it was extraordinarily painful.

We’d just had our second daughter, and I was giving her a bath in the kitchen sink of our new house we’d just bought, and the phone rang. The guy ringing — a mutual friend of my partner and Todd — never calls me, and I was looking down at the phone, like, ‘Why is this guy calling me?’ And he told me about Todd.

I went outside and broke down. My older daughter said she’d never heard me cry like that. It was like insanity, really — exactly like you said: Here is your very close friend; now they’re gone.

Like you said, you think a drug addict would be around death all the time, but I wasn’t, and I don’t think Chris was either. That’s why we could do a show like Dopey so cavalierly.

But before Todd died, a handful of other people died. The first kid was one of our first listeners, a guy named Troy. We didn’t really know him.

It was almost as though death was circling us, but it hadn’t become really apparent.

The first major death was a young man named David Marshall, whose sister set up our Facebook page. Chris had gone to treatment with Dave. He was a sick guitar player and perhaps the most handsome and athletically fit person I’d ever met. He owned a CrossFit gym in rural Connecticut, and they would play Dopey in the gym. He loved Dopey, and he was a sweet, remarkable guy.

Then Chris texted me, saying Dave had died. He and I had just become friends, and it shocked me. He was 29.

Chris took it very nonpluss. He had the ability to disconnect. Chris was the kind of person that sometimes was ridiculously invested in friendships and relationships, and other times he would totally go cold. I think it was a self-preservation mechanism.

He had said on the show one time after Dave Marshall had died that it didn’t hit him hard, but he assumed that it would in time as his life — Chris’s life — got richer and he would think about Dave and how Dave’s life wouldn’t go anywhere.

Andrew Cohen was an amazing Dopey fan. He was like this weird hippie, but he didn’t like to be called a hippie. He preferred to identify as a hobo. We had him on the show, and he was hysterical. He’s perfect. He worked on a huckleberry farm in Colorado or Wyoming or something. But his father lived in Brooklyn and Andrew came to New York to meet me. He’d gotten a Vivitrol shot that blocked heroin and had about 25 days clean. We met at a coffee shop, and he said he wanted to be a Dopey intern. He was a really sweet young guy.

And, I swear to God, the next day his father wrote me that he found him dead. He was 26.

How does the grieving go for you with all this? Does all these people dying seem utterly pointless?

When it was Todd it was devastating. And when it was Chris it was unfathomable. Unfathomable. To the point where I literally didn’t believe it.

It took hours for me to believe that it had happened. I thought his girlfriend was just lying. I thought she was crazy because he had called me the night before and told me that she was crazy.

I remember it very well. Me and Linda [Dave’s wife] were with our baby going for a walk, and I’m walking down our front porch and my phone’s ringing, and it’s Chris’s girlfriend, telling me that Chris had died. And I said to her: “Don’t say that. You know, that’s not nice.” Because I thought she was crazy.

And then it took five hours to get confirmation from his sister that he was gone. And I was so angry. With Todd I was very sad. With Chris I was angry.

What do you put that down to?

I felt like we were building this thing together based on our sobriety. We spoke every day — I literally had talked to Chris every day from 2015 until the day he died — and I felt very much betrayed.

A friend of Chris’ called me, thinking Chris was using, and Todd had died like the week before or two weeks before, so I called Chris. And Chris talked me out of it. He totally manipulated me. He told me that he was fighting with his father, and this and that.

I totally believed him because I kind of needed to.

He worked me — he manipulated me, just like addicts do. And even though I was an addict for so long, I never used with Chris, and Chris really helped me in my early sobriety. So I just believed what he was saying.

And now we’ve just lost another: an Australian kid. He loved the show and wrote me a bunch, and then his mother wrote me that he died. And there was Will M., who wrote me on Facebook. Then he died [aged 29].

Crushing.

The deaths don’t stop coming. I didn’t foresee it when we started the show, but after they started coming it became obvious to me that they were always going to come. Because the show is about heroin addiction, and now it’s all this fentanyl. And fentanyl seems to have a much higher fatality rate than heroin did. So people kind of have to die.

It’s an awful numbers game.

I’ll be sober eight years in August, and I’m not really interested in getting high — it doesn’t interest me. But before Chris died, I never really had the thought that it could kill me. And now it just seems so obvious that if I wind up using my family could lose me.

That’s the final deterrent. The normal deterrent is that I love my life in sobriety. I get to do all these things that I couldn’t do when I was using. But the death. It’s rough. Our audience is dying. And nobody seems to see it: that if you use anything there’s a good chance there’s fentanyl in it. And you’ll just drop dead. It’s a crazy reality.

Every day I think about Chris and Todd. The anger for Chris subsided really slowly. I was angry at him for years, and I might still be a little angry at him, to be honest. I don’t have survivor’s guilt, but it annoys the shit out of me that the show got so big after he died. It’s so annoying to me because it’s almost as though I benefit from his death.

Before the show we knew each other, and we knew we had the potential to be great friends, but we weren’t. So it’s another magical piece of the show that you hear our friendship develop, but it’s weird.

Do you dream about Chris?

I’ve probably had six dreams with him since he died. And with half, the root of the dream was that I was scared of doing the show without him. The first time I dreamt of him, he told me he wasn’t really dead, had faked his death, and he had started a new podcast. I was scared that I was gonna have to compete with him. Because I think there was always competition between us on the show.

But then I had a series of dreams which were terrifying.

I would go someplace and he would be there. He wouldn’t know that he was dead, but he knew that something had changed. In the first dream I had like that, I was in a hospital visiting somebody else, and he was there and he was falling apart — his skin coming off. And I had already seen him dead. At his funeral they had an open coffin, so I knew what he looked like dead. But it was also like he was undercover, wearing a trench coat with a hat and sunglasses, kind of saying, “I’m looking around before I have to leave.”

What was it like seeing Chris in the coffin?

It was horrible.

My mother died before I got sober, and she didn’t have an open coffin, but before the cremation somebody had to identify her body, and I did. She was very small and withered a little. And she was 64 when she died. Chris was 34. And he was bloated, and you could see this makeup, and I was with all of these young people. I was 10 years older than Chris, and I was 10 years older than most of the people there. It was this community, his recovery community in Massachusetts, and I remember standing in line with one of his ex-girlfriends who he talked about on Dopey all the time. And with his family who I had never met. It was painful and surreal and scary.

Did you ever go down a kind of rabbit hole of repeatedly listening to the final recordings of Chris before he overdosed — listening to those last episodes where he sounds narky and defensive and impatient? I did.

No. I think the whole thing deeply traumatized me. But every year I put out a number of shows to commemorate and honor Chris and Todd. Lately I’ve been going back to find pieces to air: special things that Chris and I did, reasons why people care, why it meant something to us. We shared so much love. We had so much fun — such a good time. Going back is like why I watch an old TV show. I don’t go back and listen to see what I missed. I go back to experience the good part, not the bad part. The ultimate bad part is that he’s gone.

And with Todd, it’s much eerier, because I know Todd from off of Dopey, so when I go back and listen to him on there, it’s eerie. He almost doesn’t belong. I didn’t let people go on the show who are using — only him. Because the show in a way was based on our friendship and how we would laugh about all the dumb shit we had done.

With Chris, it’s five years this year that he’s gone. I’ve done the show longer without him than with him. But even without him, half of the show is the fact that he’s gone. That’s the vibe: It’s the show about the dumb things drug addicts did, but the guy who started the show is dead. It’s built into the identity of the show. So he’s always with me, and he’s always with the show, but it is a crazy thing — like Dopey is Chris, you know, even though it’s my show now. I haven’t taken his name off anything.

And I got an email just now from somebody who’s listening to the beginning, and they don’t know he’s dead. That happens a lot. I get an email from someone that’s like, “Hey, Dave and Chris,” and you have to tell them that Chris is not around. And it’s painful.

Part of me thinks I should take his name off the social media so people won’t be confused, but I like to keep it there.

It’s a dramatic show you’ve made, Dave. Not like others — the stakes are real.

I know. It’s weird. It was not the plan.

We had this writer on, Ryan Leone, and I would also talk to Ryan offline, on the phone and whatever, and he said saw his death coming. He would text me all the time: ”I’m gonna die. This is gonna kill me.”

I don’t know if he really believed it. He was also into these services where it’s like: Don’t get high alone, and you call somebody before you shoot heroin or smoke fentanyl or whatever, and they make sure that you’re alive. And he was doing that.

And then one time he didn’t do it, and he died [at 36].

Ryan had two little kids: two little sons. One was like four months old.

In terms of developed countries, America leads the pack by a hell of a long way with getting hammered and dying. And the sheer numbers are mind-blowing: more than 100,000 people in America dying of overdoses in just one year at last count. Why is the level of intoxication, and the enthusiasm for it, so big here?

My experience outside of America is very limited, but I can speak to my experience inside of America, and I think it’s romanticized here. Getting wasted and not giving a fuck is romanticized in our culture and in our art. But then, at the same time, success is so highly valued that it creates so much pressure.

And once you have all this pressure on you to be accepted, to be cool, to be successful, and then you have access to all of these chemicals and all of these compounds and all of this alcohol, and then it’s also so much within our culture to consume these things, then you have a perfect breeding ground for drugs and addiction and alcoholism.

I’m certainly not a sociologist, though. I’m just a recovering heroin addict with a podcast.

What kept you going with Dopey after Chris died?

When I was a kid, I really wanted to have a talk show. Like, I remember I would go into the kitchen at my parents’ apartment and my mother would be listening to AM radio, this guy named John Gambling. And I was like, “Oh man, that seems like a good job.” And I would watch, uh, like Regis Philbin on TV, and I just loved how he interviewed people, and how he seemed to have a lot of fun. And then I really got into Howard Stern, and I wanted to have a talk show.

And later I had a little music magazine show called Shuffle that I invented on a college cable network called Burly Bear. I was a production assistant there, and then I was hosting segments. And then they offered me a job to produce a music video show.

KRS-One was in town doing a show at Tramps in New York. We went down to Tramps to interview KRS-One and shot the performance, and he was just amazing. We shot it in black and white, and it looked like film. The producer was like: “You could do whatever you want. Why don’t you do a different show?”

So they gave me a bunch of money for my show, and this was around the same time I became a heroin addict.

And for every interview I was not prepared. I was terrible. In my interview with Bob Weir from the Grateful Dead, I say to him, “Jerry was so cool, man.” I probably said that to him like four times. And he’s like, ”Yeah.” Then I ask what it was like being friends with Garcia, and Bob Weir was like giving me the stink eye. Because I hadn’t prepared. I thought I didn’t like Bob Weir, and I thought it would be funny. But ultimately I totally was a terrible interviewer.

I would interview people like the Grateful Dead or KRS-One, De La Soul, or The Flaming Lips. I interviewed all these bands that I loved, and I did such a bad job.

So with Dopey, Chris and I finally built what I had always wanted to do. It was really stupid and funny, and I felt like it was three years of me interviewing Chris. I didn’t do a great job of it. I interrupted, and I got a lot of shit for interrupting him.

But Chris and I built what I had always wanted to do. Then he died and my wife, Linda, was like: ‘You should stop doing this.” Because I was obsessed with it, and it was so sad.

I don’t know which was the real reason that I didn’t stop. I think it was because all I ever wanted was an audience in a talk show, and now I had one, but it was also that I knew that our audience actually relied on the show. Our audience was in recovery or thinking about it. I didn’t know what Dopey was supposed to be, but I knew what it had become, which was a friend to a lot of people. It was a place where they felt like life was okay. That it was fun, you know? And I didn’t wanna take that away from anybody, but I think mostly I didn’t wanna lose it — I wanted it so badly.

And after he died, I just tried way harder with interviewing. I hated people writing me emails, telling me that I interrupt too much. So I started to change that, and my interviewing got much better, and I did crazy amounts of research. I always had a knack for making people comfortable. And if I could put that together with research, I had the potential for doing decent interviews. And I think that that happened.

Dopey Dave’s Select Cuts

Top Songs I Loved Wasted

Top Songs I Loved Strung Out

Top Songs I Love Clean

And here’s Chris as a psychology student being interviewed for a show called A Deadly Silence about what was behind him. But then it wasn’t.

To see our running list of the top 100 greatest rock stars of all time, click here.

The post Taking On AC/DC Taught Me Why Most Music Biographies Suck appeared first on SPIN.