You Don't Know the Power of a Modern Simulator Until You Try One

Automakers need to reduce. Reduce emissions, reduce costs, reduce crashes, reduce complexity, reduce development time, etc. In October 2020, GM CEO Mary Barra posted something of a manifesto on LinkedIn stating the company's goals of "zero crashes, zero emissions, zero congestion." There's another "zero" phrase floating around in the automotive world, too: "Zero prototype."

The idea is deceptively simple—all automotive development happens in the virtual world, and no physical cars are built until production begins. There's a lot of debate as to whether or not a true state of "zero prototype" is achievable, but it's an ideal that much of the auto industry is chasing. Even if we never get there, it's worth aiming for. One of the key tools in this quest is the driving simulator.

Last month, the folks at Multimatic—the Ontario-headquartered supplier and racing firm best known for spool-valve dampers and the second-generation Ford GT—invited me to try the company's simulator just outside Detroit. A rare opportunity for a journalist, and a peek behind the curtain for how today's cars are developed.

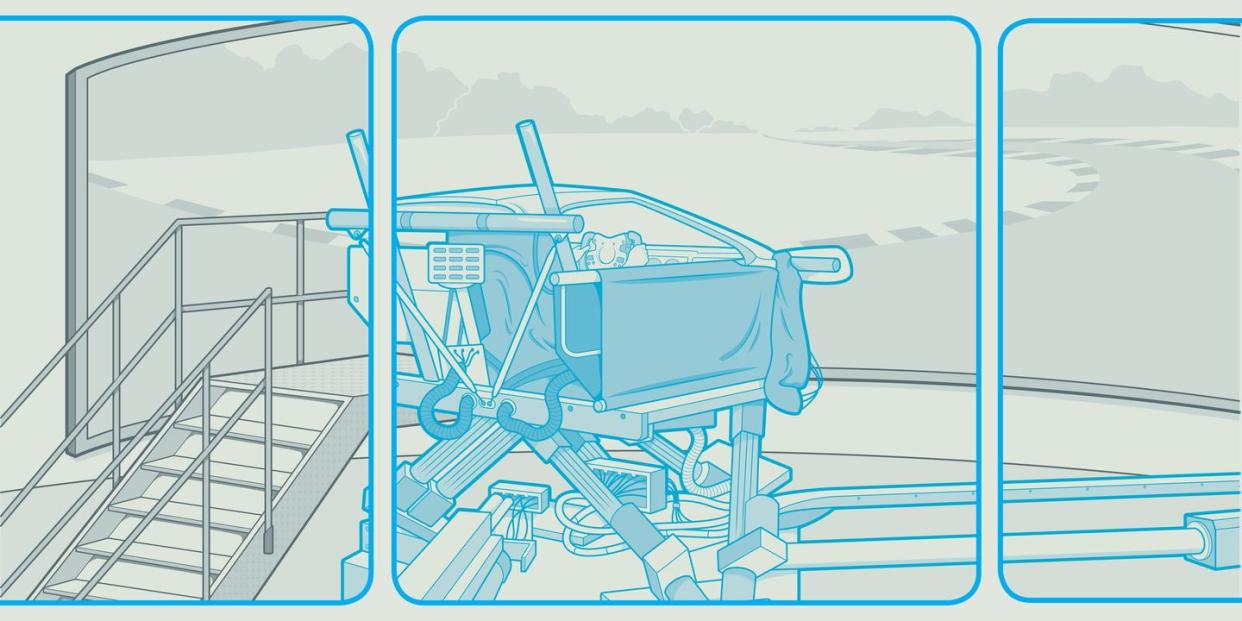

Built in collaboration with Italian firm VI-grade, one of the two major companies building simulators of this scale, Multimatic's sim is the first of its kind in the U.S. It's an intimidating sight if you're a non-engineer journalist who's about to get strapped into the thing. From the ground up, there's a steel plate covering up three air bearings which create a frictionless surface for the motion platform. Three longitudinal actuators control lateral, longitudinal, and yaw motions and can displace 2.5 meters, a stat that gives this particular system part of its name, DiM250. (VI-grade also offers cable-driven simulators that can generate over four meters of displacement.)

On the base of the motion platform is a hexapod that supports a seating buck. Those six actuators control vertical, pitch, and roll motions, and there's a redundant actuator for yaw motion. So, nine degrees of motion freedom in total. The tripod controls motions up to 8-10 hZ, while the hexapod controls motions of up to 50 hZ. "When you put that whole system together, you get the best of all worlds," says Multimatic engineering VP Michael Gutilla. "You have all the large planar motions for all your driving dynamics, and then a lot of the high frequency content that's put in through the hexapod so you can do ride comfort, and even some off-road maneuvers."

The DiM250 is so large, Multimatic had to build its offices around the rig. Surrounding the motion platform is a wraparound screen and behind it, up two flights of stairs, is a control room where the engineers sit, loading up different programs for the driver and logging data, up to 100 gigabytes a day in telemetry alone. There are three seating bucks that can be placed on top of the rig—one based on the previous Mercedes C300, one based on the previous Ford Escape, and one based on the Ford GT. For my test, Multimatic used the GT buck, as I was driving a virtual GT. The buck sits around eight feet off the ground at rest, so you need to wheel in stairs to actually hop in. Then someone has to wheel the stairs out of the way.

It's an incredibly powerful tool. I'd soon learn just how powerful.

I've played racing games since I was a kid and I've tried out motion simulators a handful of times before. This is nothing like any of that, which is obvious from the moment you strap in.

This buck was configured with a racing bucket with a five-point harness with tensioners on the shoulder belts, and the steering wheel from a GT Mk2. It feels like sitting in a blacked out version of a Ford GT because that's basically what it is, just with a Motec screen in the middle of the cockpit instead of a gauge cluster. The seat was adjusted so I could reach the pedals—I'm only 5'7"—and the steering wheel set all the way at my chest, as in a race car. You wear headphones to get simulated sounds from the machine and to talk to the control room, and they're noise canceling so you don't hear the actuators at work.

I very quickly knew I had a problem. To get acclimated, the engineers had me practice lane changes on an infinitely long highway. After a few on a lower-motion setting that tripped me out a little, motion cueing was ramped up to its max setting, 1:1. The motion of the rig corresponded exactly with real life. So, it moves around a lot. In any sim rig, it's impossible to apply constant g-force to the body, so your sense of speed gets distorted. The first time I hit the brake pedal—which is connected to a hydraulic system to provide realistic feel—I went way too hard without realizing it. The rig moved back way more than I expected. I told the control room that I was starting to feel sick, and the engineers encouraged me to step out of the machine, take a drink of water, and try to regain my bearings. If I kept trying without a break, I was only going to make myself sicker.

Realizing the rarity of this opportunity, I climbed back in. We went straight for the good stuff, a run up and down a b-road near Multimatic's technical center in Thetford, England, not too far from Lotus. I've never driven this particular road, but this job has put me on plenty of English b-roads, and I was astounded at how accurate it felt. We switched between a few different suspension setups on the virtual Ford GT, and the differences in calibration were immediate and obvious. What was great is that you can just swap setups on the fly, so you can get a real A/B comparison you couldn't hope to recreate in the real world.

I was still getting sick, though. For the inexperienced, a sim like this is like stepping into the uncanny valley. There's so much that feels real, yet it's not. I kept leaning forward in the seat, as it was reclined more like a seat in a prototype race car, but when I did, I'd see beyond the top of the screen. Suddenly you're taken out of reality, or the reality the simulator is trying to create. Other little things tripped me up, too. One of the more useful tools is a reset button on the steering wheel—hit it, and you automatically rewind 15 seconds. Great if you screw up a corner or want to try something again, or A/B test different calibrations back-to-back. When you hit the button, the screen immediately resets, but it obviously takes a few more seconds for the rig to move into the correct position. It's deeply unsettling, and even the most experienced sim drivers close their eyes immediately upon hitting the button to avoid this reality distortion. But then, closing your eyes while driving is unnatural too.

Peter Gibbons, Multimatic technical director for vehicle dynamics, tells me that comfort in the rig is really dependent on one's vestibular system. Mine, he says, must be particularly sensitive, so I'm having a harder time adjusting than most. Again, I was told not to fight through the pain and just come into the control room to debrief and drink ginger ale. Maybe even step outside for some fresh air.

After some time spent in virtual England, we moved to virtual metro Detroit to test out ride quality on its uniquely terrible roads. Again, I was blown away at how true-to-life the body motions felt in the rig, even if I was still having trouble with the rest of it. It quickly becomes obvious why this is an essential tool. After lunch, and hoping a fuller stomach might make things better, we moved to the Virginia International Raceway for some faster laps. Reader, I'd love to tell you that this is when everything came together and I set a blistering time, so impressing the team at Multimatic, they granted me a test in their newest race-car project, the Porsche 963. But it didn't. I did one lap, it made me very sick, and after a break, I did another lap and that was that. In the control room, Gibbons took one look at me and said I should probably call it for the day. I was only going to get worse if I kept at it. Horrified at the possibility, I agreed.

I'm convinced that if I had a good night's sleep, I could've hopped back in the sim and been better the next day. The brain can process a lot during sleep. I'm still desperate to give it another go. I don't simply talk about my trials with the sim because they're amusing—to me, this does a great job of demonstrating the power of the machine. It's unlike anything I've ever experienced.

Multimatic uses the sim to develop new technologies and for complete vehicles as part of Multimatic Special Vehicle Operations (MVSO), which developed the track-only Ford GT Mk2 and Mk4 and is working on the Mercedes-AMG One and Aston Martin Valkyrie. The simulator is essential to shortening the development process of bleeding-edge cars and tech. Regarding the AMG One, Multimatic COO Raj Nair, says it wouldn't be impossible to develop a car like this without driver-in-the-loop simulation, but it would take far longer to do so. The sim also allows Multimatic to trial new pieces of technology before making physical prototypes, further saving time and money.

Separately, I spoke with Cadillac chief engineer Brandon Vivian. "We're able to pick our hardware sets and our software solutions and get that fidelity sooner, which means we eliminate prototype phasing," he says. "That's really what we're able to do. And so not only is it quicker, but we're saving money at the same time where you're not prototyping parts, you're able to go right to the production part." Vivan credits driver-in-loop simulator use, plus virtual simulations with shaving about a year's worth of development time off the new Celstiq.

You can see why the time saved is advantageous for automakers. Very generally speaking a new model takes around four years, but these days, cars are changing faster than ever. Especially as cars become more software driven and updates can be pushed out over the air, automakers need to be able to respond faster than they ever have before. With a sim, engineers can try out new ideas quickly, and this helps automakers bring new technologies and entire vehicles to market in much reduced time. It's a huge part of the reason GMC was able to develop the new Hummer in around two years.

The endless possibilities of the sim do require some restraint. "We like to say that the good thing about the simulators, you can change a lot of things in a short period of time," Gibbons says. "The bad thing about a simulator is that you can change a lot of things in a short period of time."

Even with tools as powerful as this, will we ever get to zero prototype? Ask 10 engineers and you'll get 10 different answers, all compelling, but making a definitive conclusion almost impossible to form.

What is inarguable is the usefulness of tools like Multimatic's simulator. I couldn't fathom developing a modern street car without one. Time spent here, trying out all sorts of virtual combinations in such a relatively short space of time, gives engineers so much more confidence when real world testing begins. Though a VI-grade DiM250 simulator costs around $5 million, plus, you know, the cost of constructing an entire building around it, that's a small investment in the big scheme of things. Individual models are billion-dollar projects, if not multi-billion-dollar projects. Yes, it costs money to run the sim beyond the price of installation, but the savings in prototype parts alone make it well worth it. It's why VI-grade expects the market for products like the DiM250, plus both smaller and larger simulators, to grow exponentially in the next few years.

I left Multimatic's office frazzled. Not much in this job has given me such a workout, given me so much to think about. It makes me wonder what kind of effect it’s having on the car industry as a whole. I spent some time talking with Multimatic about how the rig changes how they develop their dampers. Before simulators, trying different damper calibrations meant taking dampers off the car, revalving the dampers by hand, then reinstalling them. A process that takes hours. Murray White, Multimatic's head of vehicle suspensions, says that in the sim, they can now try 50 damper calibrations in two hours. "It's just exhausting," he jokes. "You used to be able to sit and have a cup of coffee in between."

You Might Also Like