“When you’re young and struggling, you overplay to get noticed. I’ve shredded my way to success. Maybe now is a good time to just go, 'Is this serving the song?'” Joe Bonamassa has reached the next level

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

In 2003, Joe Bonamassa was nowhere. The 26-year-old guitarist had enjoyed a fast start to his career. Hailed as a prodigy, he was mentored by the likes of Danny Gatton and had toured with B.B. King. Before he reached 18, he was part of a group called Bloodline that featured the sons of Miles Davis, Robby Krieger and Berry Oakley. Everybody said “Smokin’ Joe” Bonamassa was going places.

By the mid ’90s, Bloodline was over and Bonamassa went solo. But after two critically hailed albums — 2000’s A New Day Yesterday and 2002’s So, It’s Like That — failed to click with record buyers, the guitarist took a grim assessment of where things stood.

“Things were bad,” he says. “I was dropped by one label, and another label I signed to went out of business. My booking agent dropped me. I really didn’t know what to do.”

He did the only thing he could. With a gift of free studio time (thanks to Bobby Nathan at New York’s Unique Recording), and his last $10,000, Bonamassa recorded covers of blues tunes by Elmore James, Buddy Guy, Freddie King, B.B. King and others, along with a few choice originals.

“It was basically a live gig. We didn’t have to rehearse anything,” he says. “The weird thing was, it was the first time I was honest with myself. Instead of trying to be something I wasn’t and trying to do songs that would get on the radio, I said, ‘This is the music I love. I’m going to do what I really want.’”

The whole thing was done in a week — mixed and mastered — and the guitarist called the album Blues Deluxe after a Jeff Beck Group song he covered. “It should have been called Blues Deluxe: Last Chance, Kiddo,” Bonamassa jokes. “That’s how things felt at the time.”

As Hail Mary passes go, the rationale behind Blues Deluxe seemed plausible enough. “We thought, We’ll just make a real blues record so we can tour,” Bonamassa says. “Worst case scenario, we’ll sell them out of the back of a van — which we did.”

Little by little, though, things started to turn around. A deal was struck with an indie South Florida company to distribute the record, and thanks to strong reviews, copies began to move. The guitarist soon scored opening slots for B.B.King, Peter Frampton, Foreigner and Bad Company.

“Things were beginning to break my way,” Bonamassa recalls. “We were only making a hundred dollars a night, so we sold CDs to stay out on the road. One minute, nobody wanted them; the next thing you know, we were selling 300 CDs a night. We couldn’t print ’em fast enough. I thought to myself, Okay, something is connecting.”

Twenty years later, Joe Bonamassa is the most successful and popular blues guitarist — or blues artist — working today, one who inhabits a rarified space in the music business. Along with his manager, Roy Weisman, he operates J&R Adventures, which oversees all things Bonamassa: albums, tours, merch — hell, he’s even got a cruise.

To celebrate his two-decade mark of independence, the guitarist revisited the concept of the record that started it all by recording a sequel, Blues Deluxe Vol. 2, packed with fiery renditions of numbers by Bobby “Blue” Bland, Albert King, Ronnie Earl and Peter Green–era Fleetwood Mac, among others, with a drizzle of potent originals.

Asked to describe the difference between the two albums, Bonamassa laughs. “With Blues Deluxe, I thought it might be my last record. This time, I know I’m going to make another one.”

The revisionist view is that there was some sort of grand plan behind Blues Deluxe and the start of J&R Adventures. In reality, you and Roy were just making it up as you went along.

Totally. Now there’s a lot of awareness of what we’ve done, but at the time we were just trying to get to next month. People say, “Oh, you guys were visionaries.” We were in danger of going out of business all the time. There was no fucking romance in what we were doing. Nobody wanted Blues Deluxe — even Alligator passed.

[Alligator president] Bruce Iglauer is a good friend, but I tease him all the time about that. So we put it out ourselves. We had one lady, Faye Cobb, who worked for us and administered the whole thing. We had a shitty little office that cost a thousand a month. Roy had a day gig, and I was just trying to stay on the road to make rent.

It was just step and repeat. About a year after Blues Deluxe, we went to Europe for the first time, and there was some immediate notoriety going forward. That was the beginning of what was to become.

And you were set on doing it all without radio.

Yeah. That was the very first time that things felt connected to some movement and it moved the needle. And it was because, I think, we were being honest with ourselves, or at least I was being honest. This is who I am. You know what I mean? Because up until that point, there was a lot of outside A&R and things that are like, “Hey, we need to get you on the radio.”

It was like radio, radio, fucking radio. You don’t have to be a radio artist to have a good following. And we started to prove that 20 years ago.

At a certain point, however, you guys must have sensed there was a strategy to build on.

We were making decisions as we went. Fortunately, Roy graduated from Syracuse University — he’s a CPA — so money management was always our thing. As soon as we started making money, we invested in our future and in the brand.

Our saying was, “Coca-Cola still advertises.” Think about it: Everybody knows Coca-Cola, so why do they advertise? You still have to build awareness, and you have to keep hitting people.

By 2006, you met producer Kevin Shirley and began an ongoing collaboration with him.

That’s right. In the years between Blues Deluxe and Had to Cry Today, I met Kevin, and that set the stage for what we would release with You & Me. That took things to another level.

Everything started paying off by this point. In 2009, you headlined the Royal Albert Hall in London.

Even then, we were all in with our chips on black. We spun the wheel with the DVD of that show, and it hit. Then the PBS special became a thing, and suddenly we were selling out big places. We played arenas in Europe. I look back now and it seems very simple and calculated, but it wasn’t.

Over the past 20 years, you’ve played lots of other prestigious places: Red Rocks, the Hollywood Bowl, the Sydney Opera House, Carnegie Hall —

All in my neighborhood. [laughs]

Exactly. Lots of classy joints. Was there one venue where, the minute you walked in, you thought, Okay, I’ve arrived?

That happened in 2011, the second time I played the Royal Albert Hall.

The second time? Why was that?

Because I was much calmer then. I’d already done it. That’s when the realization kicked in, because I played it once and thought maybe I couldn’t return or whatever. When I sold it out the second time, it felt different.

It’s funny: The first time you play somewhere, the place seems larger. I’ve now played Red Rocks 10 times. We’ve done the Ryman in Nashville 10 times — that’s just a couple of blocks from where I’m sitting.

This year I played Red Rocks, and I was like, “It’s not as big as I thought.” When you first stand on that stage, the seats go forever.

After a while you go, “It’s 9,000 seats and it’s cool.”

Don’t get me wrong — I’m not jaded, but I definitely feel like I’ve arrived. They’ve got my picture in the back of Red Rocks. It takes an act from the city to take the picture down.

You’ve released quite a few records…

Like, 50 of them. [laughs]

Are there any that stand out to you as real growth records?

The Ballad of John Henry was the one that set it up. Studio-wise, I’d say that one and Driving Towards the Daylight. Live, I would say Muddy Wolf at Red Rocks. I think those three represent big spikes, along with the acoustic Live at Carnegie Hall.

On that one, I had no other option than to just sing. It’s like, “You are a singer tonight, not a guitar player. You can noodle about as much as you want, but you have to sing most of the night.”

Both of the acoustic live records — Carnegie Hall and the Vienna Opera House — were the biggest challenges that, I think, made me a better artist. By the way, you can throw in the Three Kings record [Live at the Greek Theatre]. That’s one I’m proud of, too.

With Blues Deluxe, you had everything to prove. With Blues Deluxe Vol. 2, you don’t have anything to prove anymore.

Only to myself. I went to Josh Smith, who plays guitar in our band, and I said, “Do you want to produce?” He said, “Let’s do it,” and we started picking songs. I wanted to prove two things: Am I a better artist overall today than I was 20 years ago, and am I a better singer?

Coming out of the sessions, I said to myself, Twenty years ago, I couldn’t have made this as an artist and as a singer. I think I’ve improved in those areas, and I’m proud of that.

This is the first album you’ve made in quite some time without Kevin Shirley.

I talked to Kevin and said I wanted Josh to produce because I had a very specific idea in mind. Kevin approaches things production-wise a certain way, like, “How can we make this more palatable to the masses?”

On this one, I didn’t give shit. I wanted it the way I wanted it. Since Blues Deluxe Vol. 2, Kevin has produced two things for me — a new solo album and a live record from the Hollywood Bowl.

Blues Deluxe Vol. 2 sounds very authentic, almost like a blues record from 60 or 70 years ago.

That was the vision, but it’s not a soundalike record. We mess with everything. Why put on my soundalike version of something when you can hear the original? Why try to re-create somebody else’s magic? You have to put your own personality and soul into it. I don’t think we went more than three takes with anything. Ninety percent of the solos were cut live. Flaws are human. People want to hear the flaws.

Last year in Guitar World, you wrote that you were going into this record “with an eye towards curtailing your propensity to overplay.” Do you feel that you were somewhat over the top on Blues Deluxe?

At that time, I had chips on both shoulders, and I was daring someone to knock ’em off. I knew I could play guitar. But when you’re young and struggling, you want to get noticed. How do you get noticed? You overplay.

Now things are different. I’ve already shredded my way to success. Maybe now is a good time to just go, “Is this serving the song in the right way without over-intellectualizing it?” You know what I mean?

Sure, but you do play some pretty seismic stuff, like on Fleetwood Mac’s “Lazy Poker Blues.” What were you trying to bring to what Peter Green once played?

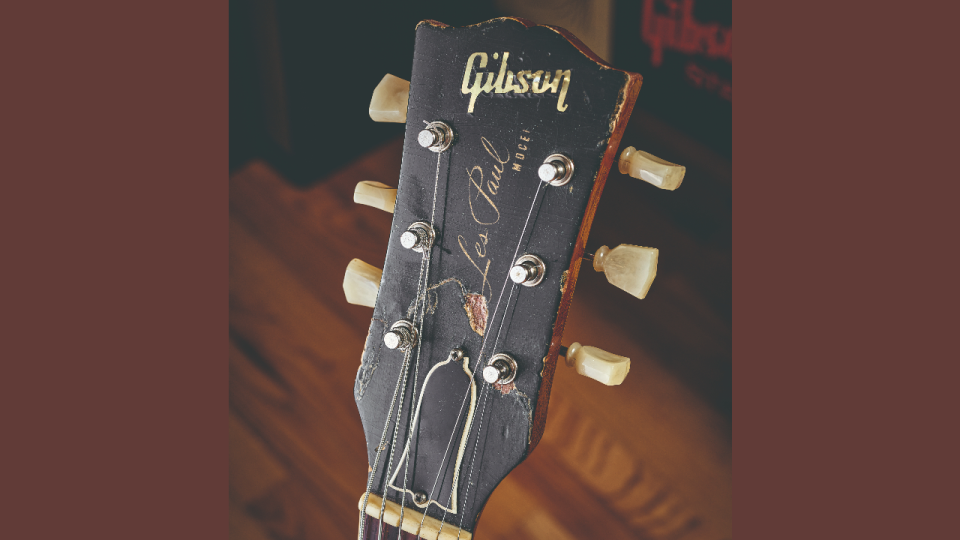

That was me tipping my hat to London blues. I didn’t go through Chicago or Mississippi — I went west, not east. The British blues was very powerful to me. “Lazy Poker Blues” was my upbeat tribute to Peter Green, and it gave me an excuse to fire up the JTM45 and a Les Paul.

And on “Well, I Done Got Over It,” the Guitar Slim cover, we could have done more of a traditional thing with more traditional sounds. But when I heard that beat, I said, “Just give me a Les Paul, and let’s just do it like Clapton on Blues Breakers.” And that was it. It’s one of my favorite songs on the record.

How about “You Sure Drive a Hard Bargain”? What did you bring to that one?

Fear. Again, you have to bring your own personality. It’s easy to play shitty blues, but it’s hard to play it right. I’ve been guilty of both. I was afraid that I was going to “Albert King” the song.

I needed to sing a song that I know in a different way and play a different way and not do all the Albert stuff, because then you can just listen to Albert’s version. It’s a very pragmatic way of looking at it. It’s a very non-egotistical way. Why would anybody listen to my version? If it’s just like Albert’s, who cares?

People reading this might be surprised that you still have fear when you record.

Fear is what drives you to be better. If you walk in with full ego and you’re like “I got this,” you run the risk of embarrassing yourself. You have to be humble in front of your musical gods, because if you’re not, they’ll bite you in the ass. Every time I play a Muddy Waters song, I’m like, “Okay, this is a big one. I’ve got to do it right.”

Joe Bonamassa's new album Blues Deluxe Vol. 2 is available to buy and stream now