“You don’t just play the root notes – there’s always harmony there to make a bassline more interesting”: How Bruce Thomas transformed Elvis Costello’s (I Don’t Want To Go To) Chelsea

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

With his biting lyrics, retro image, and jittery deportment, Elvis Costello was somehow more punk than punk when he hit the mainstream back in 1977. For his solo debut, My Aim Is True, Costello relied on bassist Johnny Ciambotti and other players from Northern California’s Clover to back a batch of tunes that showed his true potential as a songwriter.

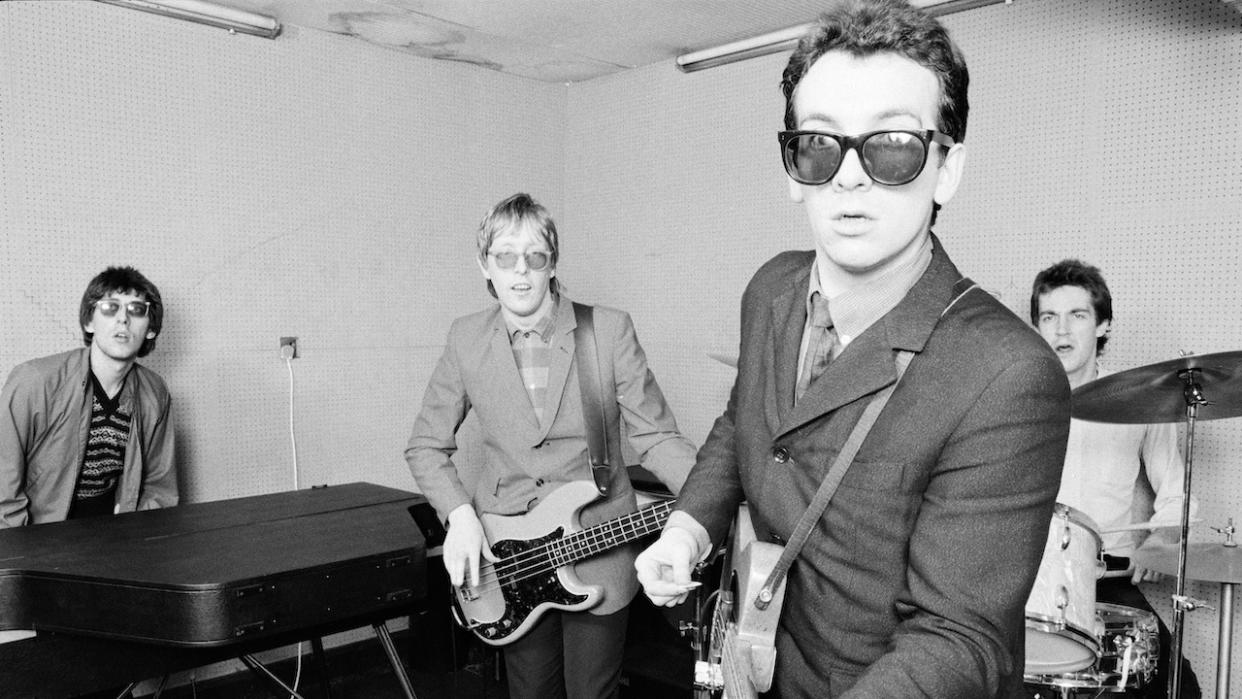

For the following year's This Year’s Model, Costello put together the Attractions – drummer Pete Thomas, keyboardist Stevie Nieve and bassist Bruce Thomas – who would set a new standard for songwriting and creativity in a genre that often emphasised style over substance, pose over performance.

For his part, Bruce Thomas took the groove sensibility of American R&B, the melodic sense of British pop, and the transatlantic energy of punk and new wave to create a signature style of bass playing that's every bit as exciting now as it was more than 40 years ago.

“In that period, I was really figuring out what my bass playing was all about,” Thomas told BP. “I was having a lot of musical epiphanies; because the quality of the songwriting was so good, the material was there to work with. I had figured out that you don't just play the root notes, there's always harmony there to make a bassline more interesting.”

Back in July 2014, fresh off some recent sessions with British pop singer Tasman Archer and American folk-rock outfit The Weepies, Thomas dialled in to talk about the heyday of the Attractions and of its most auspicious debut, (I Don't Want to Go To) Chelsea.

I understand Chelsea came together the very first time the Attractions played together. How did that happen?

“It was actually the first track that we worked on. We began playing through some of the songs we played at our separate auditions. Then Elvis played us a new song he'd only just written, a slow, chordy, riffy song a bit like The Kinks’ Tired of Waiting for You. Anyway, to me it seemed the tempo was way too slow for the song; it would go on for ages. So after a pause, I began playing the sequence as an arpeggiated riff, that was a bit spikier and more urgent.

“It was a bit like the bassline I'd heard John Entwistle play at the end of the live version of My Generation, after the key change at the end; while Pete Townshend was power chording away, and Keith Moon was doing his buffalo stampede, Entwistle played a part based around the main notes of the chord. Anyway, that's what I started doing and everyone fell in with it. After a few more plays to work out a drum intro, an ending and a few variations on the riff idea for the chorus, we had our first group arrangement.”

What bass did you play?

“That was my 1965 Fender Precision. That was my main bass guitar – I got it from Ashley Hutchings of Steeleye Span and had it for five or six years at that point. I shaved the body down to make it more lightweight, I sanded the neck for a flatter profile, I reverse-wound the pickups, and I did a few other things. That guitar had quite a ‘whiney’ sound because of the pickup winding.

“The action was a bit too low, so there was a lot of fret buzz and string rattling giving it a funny sound. Fortunately we had a bass player as a producer in Nick Lowe, so they got the bass to sound pretty good. The body was unfinished at that point, but I later had it sprayed Salmon Pink, thinking that was the original Fender colour. Of course, the original colour was Fiesta Red.”

Like the one Jet Harris played in The Shadows?

“When Fender started importing instruments into the UK in the early ‘60s, everyone wanted a red finish like the ones Hank Marvin and Jet Harris played in The Shadows. Fender in Britain would spray red over whatever colours they got. Fender UK didn't have the same DuPont lacquer they had in the States, and the Fiesta Red came out looking pink.”

What kind of setup did your basses have back in the day?

“I used to play with a high action and heavy strings: .055, .075, .095, .110. It was almost impossible to bend the strings, so when I'm bending strings on songs like This Year's Girl, that is full-force string bending! It was very physical.”

How much freedom did you feel in building basslines with the Attractions?

“We were all left to our own devices. I pretty much played what I heard and nobody said, ‘Don't play that.’”

Aside from Pump It Up and Every Day I Write The Book, Accidents Will Happen is another great bassline.

“On that one, I was trying to re write a neo-classical Bach-type bassline. I realised you could string notes together by taking, for example, the root of the first chord and linking it to the third of the next chord, and then the fifth of the next chord, etc., and string them together so they make coherent structures.

“For example, take the bridge to Party Girl. I start the bridge on the highest note that'd fit in the first chord – root, third, fifth, it doesn't matter. Then I slid down to the lowest note on the same string that'd fit in the next chord, then up to the next highest note to fit in the next chord, and so on. The song is about a slightly drunk girl tottering around in high heels; the bassline becomes a kind of musical metaphor to match the lyric.”

Though well matched musically, Costello and Thomas had personal differences that came to a head – as things do, after years on the road – with Thomas coming and going as Costello branched out to work with other bass players.