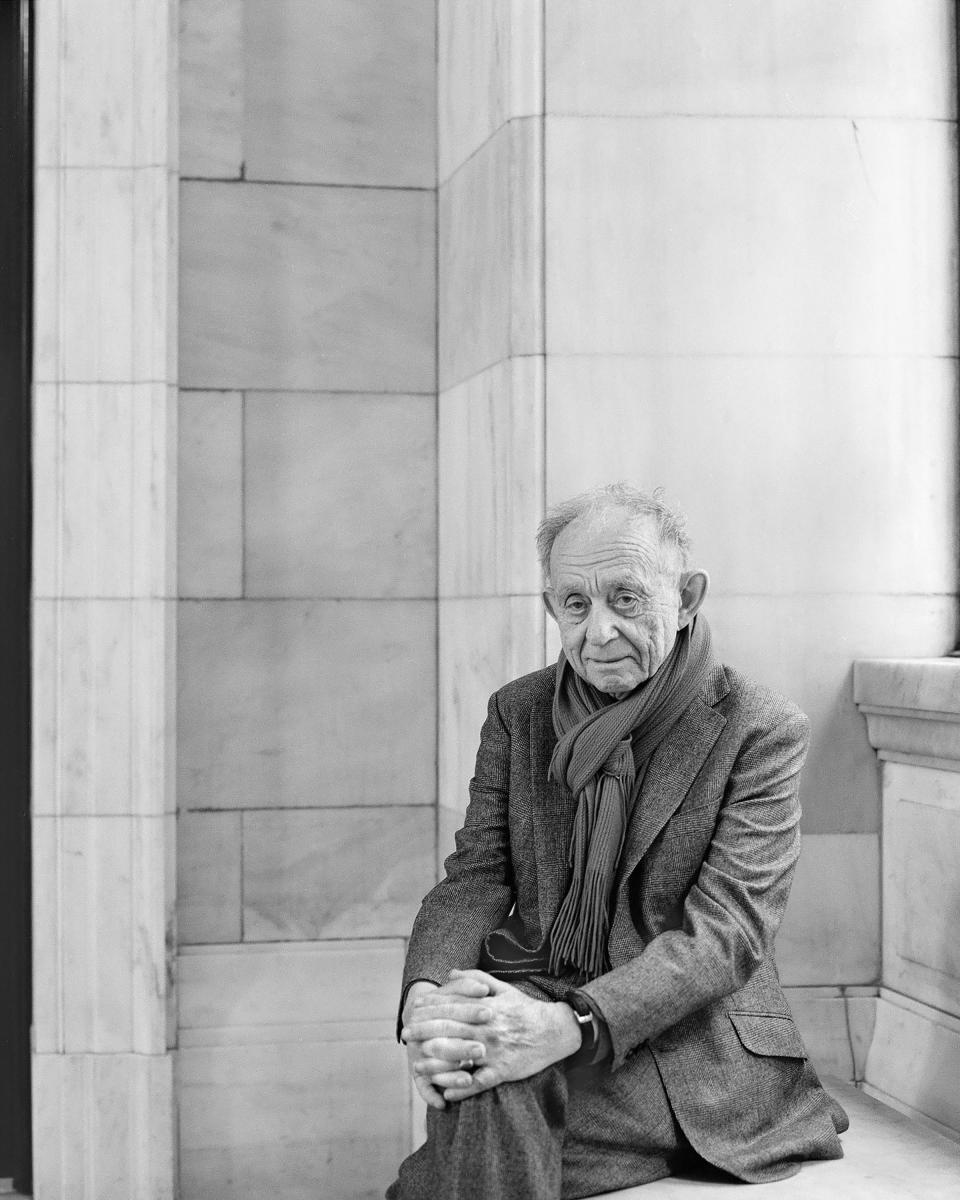

Documentary Legend Frederick Wiseman Prepares A Cinematic Feast In Oscar Contender ‘Menus-Plaisirs Les Troisgros’

The table is set for Oscar shortlist voting to begin on Thursday. In the documentary feature category, Academy Doc Branch members will be choosing from a buffet of 167 films, among them Frederick Wiseman’s Menus-Plaisirs Les Troisgros.

The filmmaking legend’s latest documentary reveals in his characteristically meticulous style the workings of several restaurants in rural France owned and operated by the Troisgros family for going on a hundred years. Their signature establishment, Le Bois Sans Feuilles, is acclaimed as one of the finest restaurants in the world, with the Michelin stars (three of them) to prove it.

More from Deadline

Carrying on the culinary tradition is chef Michel Troisgros and sons César and Léo (Michel’s wife Marie-Pierre runs a family-owned hotel). Wiseman, who turns 94 in a few weeks, lives for much of the year in Paris, and traveled to the area of Ouches outside Lyon to document the Troisgros’ and the artistry they bring to haute cuisine.

DEADLINE: When did you first hear about this family, and their several restaurants?

Fred Wiseman: I first heard about them in the summer of 2020. It was the height of COVID in France and I was staying at a friend’s house in Burgundy to avoid living in Paris. And I wanted to thank them for putting me up for a month. So, I looked in the Guide Michelin for a good restaurant nearby and I found the Troisgros and we went there for lunch. After lunch, César, who’s the fourth generation Troisgros, came out and worked the room as the chefs always do, came around to the tables and said hello, et cetera. When he came to our table, after we exchanged our initial pleasantries — without planning to do it — I sort of blurted out that I made documentaries and would he ever consider having one made about his restaurant. And I hadn’t thought about it at all. He said, let me talk to my father. And he came back about a half an hour later and said, “Why not?”

I discovered a year later when I showed the whole family the film that the father wasn’t there that day. But what César had done was look me up in Wikipedia. I gather he liked what he read.

DEADLINE: I read that you had wanted to do a documentary about a restaurant for some time.

FW: It was on my life wish list, but I hadn’t approached any restaurant.

DEADLINE: Why did the environment of a restaurant intrigue you?

FW: Well, because eating in good restaurants is a semi-religious event in France, and certainly for me, because I like to eat in good restaurants. When I was a student here [in France] in the ’50s, I couldn’t afford to go to them. And so they always held a certain mystery and fascination for me, and I wondered how they were run. Since I don’t have a very precise definition of institution, it’s not a problem to declare it an appropriate subject consistent with the other subjects I’ve chosen [for films].

DEADLINE: Your work is often reduced to the thumbnail description of, “He makes documentaries about institutions.” I like how Manohla Dargis, the New York Times film critic, put it in her review of Menus-Plaisirs. She reframed the nature of your work as looking at organizations, and people moving through them.

FW: Yes, that’s a good characterization. I mean, I have no precise definition of institution, or organization.

DEADLINE: One of the things that I think is certainly fascinating about the film — it almost makes me think of your film about ballet, in that there’s a choreography among the staff.

FW: I’m glad to hear you say that because I think that’s the way I tried to edit it, particularly in the kitchen.

DEADLINE: It’s delightful. It’s almost as if the hand of God is sort of manipulating these movements so that they all work correctly and people aren’t just colliding with each other.

FW: Well, it is not the hand of God, but it’s the hand of the editor, me.

DEADLINE: But in terms of the movements within the kitchen, it is years and years of process. There are young people in there too, being integrated into this organization. It’s like, how does this thing work? How do they not collide with each other? How does somebody not wind up with a knife in their side by accident?

FW: While many of the people working in the kitchen are in their 20s, they’ve been working in kitchens since were 17 or 18, or in some cases 15. They’re agile and they quickly get adapted to the routine. I was very conscious when I was editing of cutting on movement and on their movement.

DEADLINE: You don’t use a musical score in the film. It occurred to me that if you had decided to incorporate a particular song, it might be “Putting It Together,” by Sondheim. “Bit by bit, putting it together. Piece by piece… the art of making art.”

FW: That’s exactly it — studying the material, editing the individual sequences, and then figuring out how they fit together.

DEADLINE: One phrase that I think is very important in French, and says something about the culture, is “Comme il faut.” Meaning “as it should be.” There is a proper way to do things.

FW: Right, exactly.

DEADLINE: And this is embedded in so many aspects of the Troisgros restaurant operation, maybe most exquisitely in the setting of the table. There’s a proper way to do it.

FW: The Troisgros family is very precise in what they want. It is an art form. Particularly in the kitchen, but running the whole restaurant is an art form, and it’s like ballet or theater, it’s ephemeral — more ephemeral than ballet because it doesn’t last as long. But what they create is beautiful, not only to the taste, but to the look. Owner Michel looks at each plate before it leaves the kitchen for the dining room. And the design, the placement of the food on the plate, has to correspond to their sense of what the appropriate design is for that dish.

DEADLINE: You capture an interesting detail – the guy wearing white gloves to set the table. I’m not sure too many Americans would think to put on gloves to do that. But who wants to have a fingerprint on their wine glass?

FW: They pay attention to every detail, and they have a long tradition. The family went into the restaurant business almost 94 years ago, and they’ve had three Michelin stars for 55 years. That is some achievement. To maintain that high quality of food for all that time, it’s a remarkable feat.

DEADLINE: I think one of the great mysteries of your films is how you decide where to place the camera. I don’t know how you do it because it reveals something that other filmmakers just simply wouldn’t capture. I’m curious about your thoughts behind the camera as you’re shooting. Are you at times saying to yourself, Ah, this is a fantastic shot? This is going to be –

FW: Sometimes you think it’s a fantastic shot, but most of the time you can’t think about much of anything except getting a shot because you have to take into account the framing. You have to take into account what else is going on. You have to take into account not interfering with the [restaurant] work. You have to move extremely fast and make decisions. And a movie like Menus-Plaisirs is made up — I’ve never accounted them — but I wouldn’t be surprised if it was hundreds of thousands of decisions between the shooting decisions and the editing decisions.

DEADLINE: I wonder from your point of view, what people typically get wrong about your films. I think one of them is describing you as a vérité filmmaker. “He’s fly on the wall,” which is not really what you’re doing.

FW: First of all, the notion that it’s truth — cinéma vérité is just a pompous French term, which you can’t take seriously. I’m satisfied with saying I make movies. I don’t like ‘observational cinema’ because it’s too passive a phrase. Because you’re not just sitting in a corner shooting what’s going on. You’re moving around all the time. You’re shooting at every possible angle that you can think of because you want the coverage for the editing, and there are all kinds of different compositions. So observational cinema, to me — it may not be fair to the people that invented the term or the people that use it seriously — suggests just sitting in a place and observing what’s going on and shooting it. For my movies, we’re moving all the time.

DEADLINE: It occrurs to me that in the context of a restaurant, the last thing you want is a fly on the wall. Or in your soup.

FW: Fly on the wall is such a condescending expression. I haven’t met any flies that were conscious. Making one of these movies, there’s a lot of instinctive shooting, but there’s also a lot of — if you have time to try different angles, you’re consciously making selections. And that’s a bit more aware than a fly.

DEADLINE: Menus-Plaisirs Les Troisgros was named Best Documentary by the Los Angeles Film Critics Association over the weekend, and by the New York Film Critics Ciricle. It was also named to the top 10 best films of the year list by the aforementioned Manohla Dargis of the New York Times, and by fellow Times critic Alissa Wilkinson. To what degree, at this stage of your career, do you pay much attention to awards? How meaningful are they to you?

FW: Of course, I like it if a group of critics respond to the film that way. There’d be something wrong with me if I didn’t like it — which is not to say there isn’t something wrong with me, but not because of that. And it is always satisfying when people like your movies, whether it’s critics writing about them or giving awards, or just somebody telling you, “I really liked that film.” It’s nice that the work is recognized, and that people see it.

Best of Deadline

2023-24 Awards Season Calendar - Dates For Oscars, Emmys, Grammys, Tonys, Guilds & More

New On Prime Video For March 2022: Daily Listings For Streaming TV, Movies & More

Sign up for Deadline's Newsletter. For the latest news, follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.