Director Paolo Sorrentino Summons His Painful Past For ‘The Hand of God’ But Wants People To Know “A Future Is Always Possible”

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

By any yardstick, Paolo Sorrentino has had a lot of good luck in his directing career. His first film premiered at the Venice Film Festival in 2001 and the next six competed at Cannes, a residency that brought an Oscar nomination for 2013’s The Great Beauty. But Sorrentino does not take his good fortune for granted. In Netflix’s The Hand of God he reflects on the twist of fate that saved his life as a teenager in the 1980s, when a freak accident claimed the lives of both his parents. Starring Filippo Scotti as Fabietto, the film is a lightly fictionalized account of the artist as an introspective young man, with a Sony Walkman on his hip and an obsession with S.S.C. Napoli footballer Diego Maradona…

Netflix

More from Deadline

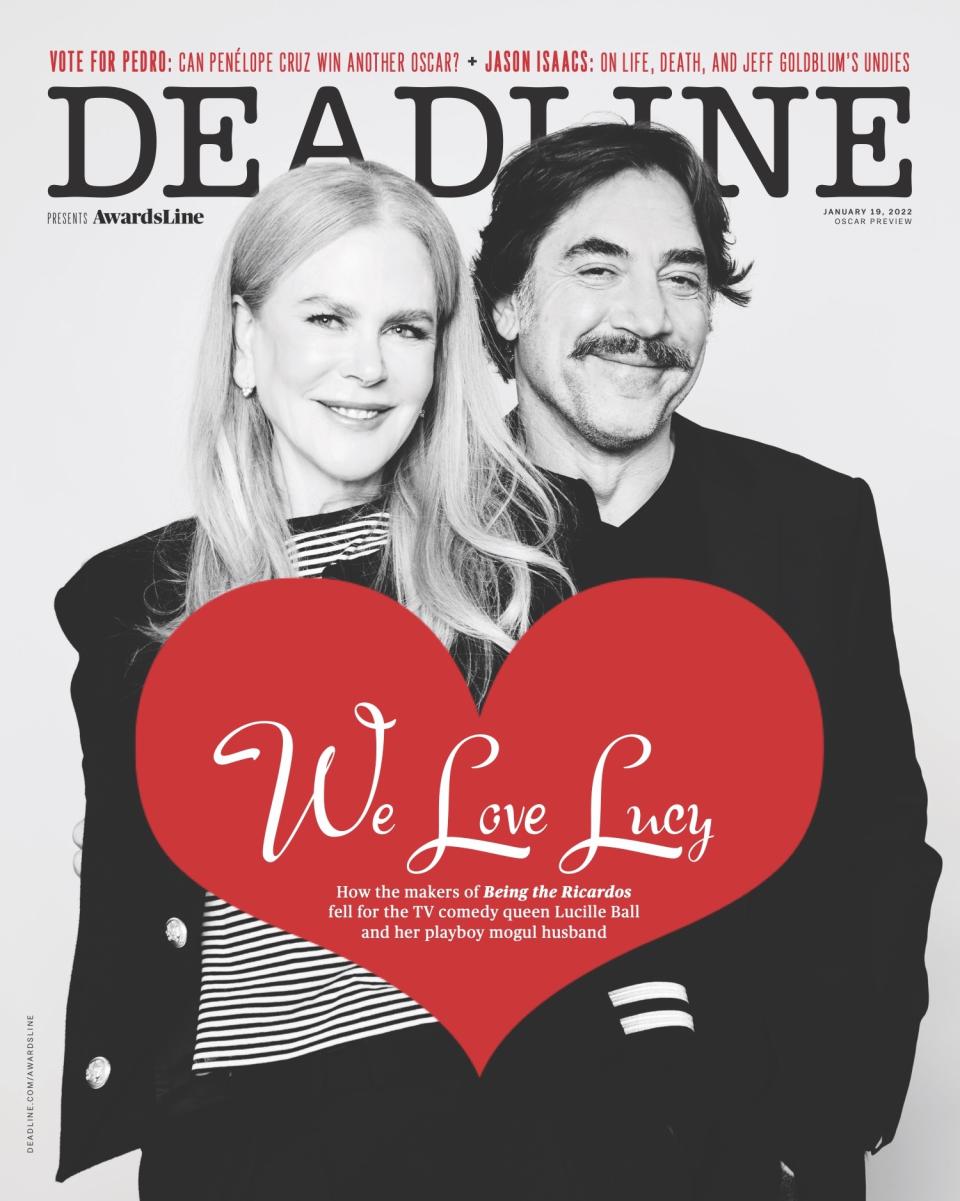

We Love Lucy: How Nicole Kidman & Javier Bardem Became The Ricardos For Aaron Sorkin

Sundance Review: Netflix Documentary 'Jeen-yuhs: A Kanye Trilogy'

DEADLINE: When did you first decide you wanted to tell this story?

PAOLO SORRENTINO: I started to think about this movie 10 years ago, but I had some modesty [issues], and so I just wrote the script. At first, I put together some memories and then three or four years ago I decided to write a script, just to let my son and my daughter read it. But a couple of years ago, during the pandemic, I decided to do a movie. I thought it was the right moment to do this kind of movie—I thought that I had the right distance from the events of my teenage years in order to face this movie without too much pain.

DEADLINE: What was the writing process like?

SORRENTINO: The writing was very involving. It’s always very involving. The writing is a moment where I am alone with myself, and so I can let go of all my feelings, and this was painful. I mean, it was also joyful, because the first part of the movie is more joyful. But the writing was hard, because of the pain.

DEADLINE: Was it entirely based on your own memories?

SORRENTINO: Yes. A few things are invented. Sometimes I changed the chronology in order to create a kind of dramaturgical architecture. But mostly, the things are real, and the feelings are real.

DEADLINE: It starts with a very interesting sequence, which may or may not be real, when your aunt has a meeting with something called The Little Monk…

SORRENTINO: It’s something that my aunt told me years ago that happened to her. [Laughs] Of course, not all of us in the family believe that it was real, but she told us this story like it was a real thing that actually happened to her.

DEADLINE: What is The Little Monk?

SORRENTINO: The Little Monk is—how can I say?—something that has its roots in the Neapolitan tradition. He’s kind of a ghost, something that people sometimes say that they see, but it’s a popular belief that dates back years and years.

DEADLINE: How accurate a portrayal of ’80s Naples is this? Have you romanticized it at all?

SORRENTINO: I tried to be as realistic as I could about the Naples in my memory, and the city you see in the film is pretty close to that city. Yes, I think it’s very realistic, because me and the people that work with me, I think we have good memories. We did a lot of research to confirm our memories, and so the city is pretty close to the reality of the ’80s.

Kilpin/MEGA

DEADLINE: It shows a different side to Naples than the one we often see. We see a lot of crime films set there, especially from Italy…

SORRENTINO: Oh yeah. A big city has many [aspects], so, of course there is criminality there. I grew up in a middle-class family, so my reality was different. It was a far from the criminality.

DEADLINE: Were your family very involved in the process of making this film?

SORRENTINO: No, not too much. Not too much. After I finished it, I showed the movie to my brother and my sister. But just this.

DEADLINE: And how did they react?

SORRENTINO: In the end, well. They were very moved, and, yes, in a general sort of way, they had a good reaction. I don’t know their real reaction, that’s just what they told me: that they were happy about the movie.

DEADLINE: It’s a very different film to your previous work, but it’s also similar in that you have a very reluctant hero. Do you see any connections?

SORRENTINO: No, it’s definitely a different main character. For me, it’s a new experience, because I was used to making movies with adults, and sometimes with old people. And this is the first time that the main character was a young person. But maybe there are other things that are in common. I am used to using the main character as a sort of observer of life—somebody that’s a little bit on the sidelines. And for the first hour of the movie, this character is an observer. He looks at how his family lives, how his family works, and then he becomes a real main character in the second part of the movie, when he realizes he’s alone and he has to face the pain, and survive, and have an idea of a future.

DEADLINE: What were you looking for when you were casting Fabietto—did he have to look like you and behave like you? What qualities were you looking for?

SORRENTINO: When I was 17, 18 years old, I don’t think that I had many qualities, so I was not looking for that. Maybe I was looking for someone without qualities, just a shy young boy with some problems that are very common in adolescence. So, I was looking for just a shy guy, a shy actor. And of course, I was looking for a good actor to do all this, because playing an observer can be difficult.

DEADLINE: He always seems to be carrying a Walkman. Is that true to life?

SORRENTINO: Yes. I had a Walkman. Not all the time, like him. But, mostly, yes.

DEADLINE: What did you listen to?

SORRENTINO: I was always listening to Talking Heads, the Cure, and many other groups from that era that I’ve probably forgotten.

DEADLINE: It’s interesting that you don’t use that kind of music on the soundtrack—and you have used it in some of your other movies.

SORRENTINO: Yes. I preferred to make a period movie in a different way, without underlining too much the mood and the environment of that decade. It’s a decade with a very strong imprint, and I wanted to take a step back from that in order to give more importance to the characters than the ’80s. So, I preferred to not use the music of that period.

DEADLLINE: Is it fair to say that everybody in Naples at the time was obsessed with Maradona

SORRENTINO: Yes. In Naples, Maradona was a big star. He was not only a big, important player, but he was a man with an unbelievable charisma. And Naples was a city that was living, at the beginning of the ’80s, through a very dark moment, so the arrival of Maradona brought a sort of hope. The news was very exciting for all the population—and above all for my generation. Because we were young, and for us it was joyful. Like a big party.

DEADLINE: Did you ever think about making the film without showing what happened to your parents? Was there a version of the script where that didn’t happen?

SORRENTINO: No. I think that if you’re going to make this kind of movie, you have to be sincere. And I needed to find the courage to show the harder times of my life.

DEADLINE: There are two scenes that involve other filmmakers. In first one, your brother auditions for Federico Fellini. How much of that scene actually happened, and what were your own thoughts about Fellini?

SORRENTINO: The audition was real, but at that time I didn’t have a big experience of movies. I was not a fan of movies. My brother had this idea that he was going to become an actor, but it was not so important for him, just something that he was going through in that moment of his life. Fellini used to come to Naples to find the right faces, because he believed that Naples was a city full of beautiful faces that would be useful for his movies, and the audition happened exactly like it happens in the movie. But I discovered cinema later. At the beginning, it was just my brother who was a fan of the movies. I was not so involved in the cinema world.

DEADLINE: Were you reluctant to become a filmmaker?

SORRENTINO: No. Let’s say… [Pause] No, I was not reluctant. I did want to become a filmmaker. The thing is—as I say in the movie—that it seemed like utopia to me, because I came from a social environment that had nothing to do with cinema.

DEADLINE: The second scene involves Antonio Capuano, who’s a very important figure in the film. Does that scene reflect your actual experience with him?

SORRENTINO: Yes. Antonio Capuano is a real director that I met when I was a little bit older. I put him in the movie earlier, but I met him when I was 24. That long scene is the result of many conversations we had with each other.

DEADLINE: He’s not as well-known as Fellini. How would you describe him?

SORRENTINO: He’s a very, very good director. His first two movies [Vito and the Others, 1991, and Sacred Silence, 1996], in my opinion, were very important movies. What else can I say? He is a good friend. He taught me the things and the thoughts that I put in the movie.

DEADLINE: He seems to be a very passionate man. Is that what inspired you?

SORRENTINO: Yes. He was, and now he’s 81 years old and he’s still passionate about life and the movies. He taught me a lot.

DEADLINE: In terms of content or style?

SORRENTINO: It was more in terms of [capturing] emotions. Not style so much, because our styles are very different. He taught me to go to the bottom of things, and not to stop at a superficial need, which is the mundane [way] of just wanting to make a movie.

DEADLINE: How did you become a filmmaker?

SORRENTINO: I started to write, at the beginning. For some years. I was a screenwriter, I started to work a little bit for television and then in 1998, I wrote a movie for Capuano called The Dust of Naples. Naples at that time, in the 1990s, was a city full of directors. There was a sort of movement of filmmakers, and I knew some of them. One of these, Nicola Giuliano, was my future producer, and together, we decided to try to do a first movie with me as director. So, I was a screenwriter for a while, and then I wrote my first movie, One Man Up [2001].

DEADLINE: But you didn’t go to film school?

SORRENTINO: No, I didn’t.

DEADLINE: That’s very unusual.

SORRENTINO: Yes. But in Italy, there is also tradition that you can learn how to make movies by working on the sets of other people’s movies. I had a little bit of experience with short movies, or on movies by other people. And before doing my first movie, my friend produced my first short movie [Love Has No Bounds, 1998], in order to help me understand how filmmaking worked.

DEADLINE: What were your thoughts on Italian cinema when you started out?

SORRENTINO: When I started in the ’90s I was lucky because the Neapolitan directors were very interesting, and I was very inspired by them. Not just Capuano, there were others. I could see something was starting to change in the Italian cinema, because suddenly there were unusual directors, less traditional, and they were able to do good movies and get good audiences. So, it was very inspiring for me at the beginning.

DEADLINE: You seemed to be successful very, very quickly—you were in the Venice Film Festival with that first film.

SORRENTINO: Yes. Not in competition, in the parallel side-event. I was also very lucky because my second movie [The Consequences of Love, 2004] was in competition in Cannes.

DEADLINE: You’ve always had a very recognizable style, which you’ve refined over the years. With a lot of directors, we don’t tend to see that until they’ve hit their stride…

SORRENTINO: Yes. When I was young, I was very, very… Well, not only when I was young, even now. But at the beginning, of course, I was very impressed by Martin Scorsese’s movies, and his directing style. And so, I was probably inspired by him, and I decided that my style, and the movies that I loved to do at that moment, needed a sort of complexity in the interaction between the camera and the actors. [Pause] Yes, this is something that—probably—I learned by looking at Martin Scorsese’s movies.

DEADLINE: And you have your own Robert De Niro in Tony Servillo.

SORRENTINO: Yeah. We met very early when I was young—he was a famous theater actor, and we started to work together. I was lucky, because I found not only a good actor but a friend, and I have a great relationship with him.

DEADLINE: What is it about him that you find so interesting?

SORRENTINO: He’s versatile and he’s very courageous. He’s an actor that’s available to accept the challenges.

DEADLINE: You’ve been a regular at all the major international film festivals, and your films are always well received there. Have they been as well received at home, when you deal with subjects like the mafia, or Silvio Berlusconi, or the pope?

SORRENTINO: Overall, I’d say they’re very well received in Italy. Il Divo was very well liked by the audience, Loro less so. But the pope series did very well. They were not movies that gave rise to a lot of controversy. Maybe for the first few days, but that was quickly over.

DEADLINE: Speaking of the pope series, how did that come about?

SORRENTINO: I’d always been very curious about the world of the Vatican, which is a state and it’s a closed one, an inaccessible one. This lack of accessibility is curiosity-inducing in general, and for me it is so in a very strong way. When I first met Lorenzo Mieli, the producer, he invited me to make a TV series about Padre Pio, who’s a very famous and well-revered figure in Italy. There had already been two TV series on him, so I didn’t think it would be useful to have a third one. I got back to him saying that maybe the right time had come to work on satisfying this curiosity about the Vatican that I had, without taking a kind of “scandalistic” approach, which had been often associated with that world.

DEADLINE: To go back to The Hand of God, would you say that this is the end of a certain chapter of your filmography? Do you think you’ll make films differently from now on?

SORRENTINO: I really don’t know. I think this movie was different from the other movies, and this required a different style. A different approach to the use of the camera, and to the use of the actors. It was a movie with a different tone, a different mood, compared to the other movies. Is it something that will give me the keys to change the style for the next movie? I really don’t know. I will find out as soon as I do a new movie.

DEADLINE: What kinds of stories attract you?

SORRENTINO: I like to explore unknown worlds and, mostly, things that I am not familiar with at all—things that are, in general, difficult to get to know. So, I start off by conducting research. Of course, it wasn’t like that for The Hand of God, which was about my life, therefore it was about a world I knew very well. But for all my other movies, I like to tackle mysterious worlds. And, little by little, I like to cast light on this mystery.

DEADLINE: What would you like people to take away from The Hand of God?

SORRENTINO: Now that the movie has been released in Italy, I was very pleased to hear that many young people have been going to see it. And this makes me very, very happy, because that was my dream, my desire. Because I would love people to leave this movie with the simple idea that a future is always possible, even when things in life make you see everything in darkness, without any light. The very simple idea of the movie is that, beyond the darkness, there is always a future, one that everybody can face.

Best of Deadline

Cancellations/Renewals Scorecard: TV Shows Ended Or Continuing In 2021-22 Season

New On Prime Video For January 2022: Daily Listings For Streaming TV, Movies & More

Winter Premiere Dates For New & Returning Series On Broadcast, Cable & Streaming

Sign up for Deadline's Newsletter. For the latest news, follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.