‘I Didn’t Kill My Wife!’ — An Oral History of ‘The Fugitive’

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

When Gene Siskel and Roger Ebert sat down at the end of 1993 to pick their 10 favorite movies of the year, they largely selected prestige, Oscar-bait films like The Piano, The Age of Innocence, The Joy Luck Club, and Schindler’s List. They skipped nearly all of the big multiplex hits of the year, including Jurassic Park, Sleepless in Seattle, and Mrs. Doubtfire, making an exception only for The Fugitive. It’s an honor they didn’t give to Die Hard in 1988, The Terminator in 1984, Aliens in 1986, or many other great action movies of the VHS era.

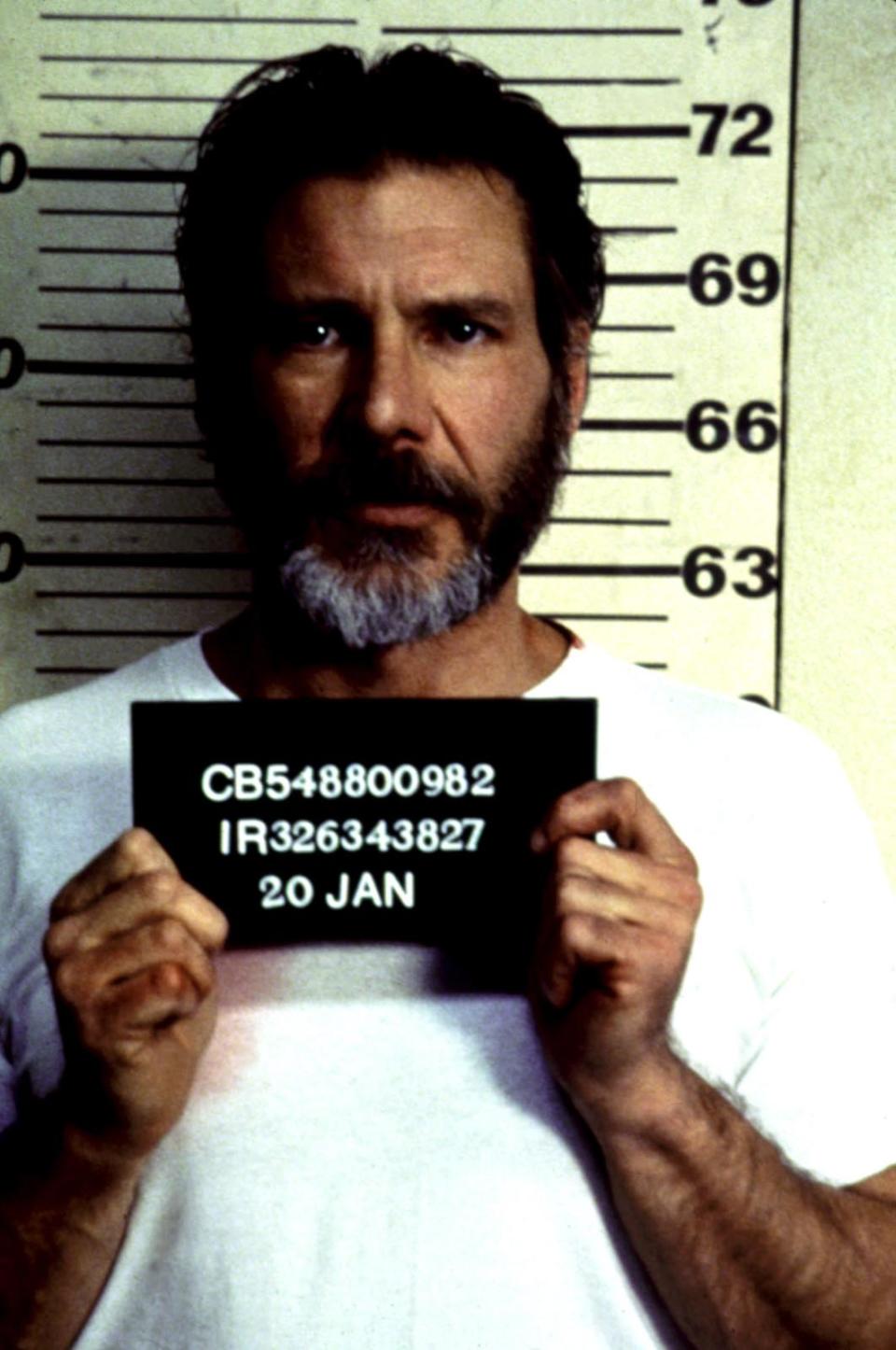

But The Fugitive, starring Harrison Ford and Tommy Lee Jones, is a special work that rises above nearly every other movie of its kind. Based on a long-running — and slyly subversive — TV show from the Sixties, the film grabs you right from the opening scene where Ford’s character, Richard Kimble, a respected doctor falsely accused of murdering his wife, escapes from police custody when his prison bus collides with a freight train. And it keeps up the relentless pace until the final scene where dogged U.S. Marshal Samuel Gerard, played by Jones, tracks him into the bowels of the Chicago Hilton. There’s no CGI, romantic subplots, or anything that distracts from the central narrative or feels the least bit inauthentic. (Well, besides Kimble’s swan dive off a dam that almost certainly would have killed him.)

More from Rolling Stone

“Thrillers are a much-debased genre these days, depending on special effects and formula for much of their content,” Ebert wrote in a four-star review. “The Fugitive has the standards of an earlier, more classic time, when acting, character and dialogue were meant to stand on their own, and where characters continued to change and develop right up until the last frame. Here is one of the year’s best films.”

To celebrate The Fugitive‘s 30th anniversary, we compiled an oral history of the movie featuring new interviews with actors Tommy Lee Jones, Joe Pantoliano, Sela Ward, Daniel Roebuck, Jeroen Krabbé, L. Scott Caldwell, and Tom Wood [click here for more from Tom], director Andrew Davis, screenwriters David Twohy and Jeb Stuart, producers Keith Barish and Stephen Joel Brown, editor Don Brochu, and casting director Candy Sandrich. (We tried to track down Harrison Ford, but much like Samuel Gerard, we just couldn’t seem to catch him. To be fair, he’s just a teeny bit busy at the moment.)

It’s a four-decade saga that touches on the original TV series, the long, difficult process of turning it into a workable screenplay, the high-stress shoot that began before they even knew how it would end, the Academy Awards, the disappointing sequel most people forget, and the movie’s long afterlife.

I – The Original Fugitive

On September 17, 1963, The Fugitive television show premiered on ABC. Inspired by the real-life story of Cleveland neurosurgeon Sam Sheppard — who was arrested in 1954 for murdering his pregnant wife and ultimately exonerated — it centered around Richard Kimble (played by David Janssen), a doctor convicted of murdering his wife. He escapes prison when a train taking him to death row derails. Throughout the four-season run of the show, Kimble attempts to track down a one-armed man he saw commit the crime, while being pursued by dogged police detective Philip Gerard (played by Barry Morse). The 1967 series finale was viewed by more than 78 million people.

Tommy Lee Jones (Deputy U.S. Marshal Samuel Gerard): It was about a decent, innocent man, ostracized by society, being chased by someone that was right, but also wrong. The formula was new and intriguing.

L. Scott Caldwell (Deputy U.S. Marshal Erin Poole): That was my favorite show when I was young. He was in peril every week, and every week he’d just narrowly escape getting caught, and narrowly escape the opportunity to catch the one-armed man.

David Twohy (Screenwriter): He goes into communities and solves other people’s problems without solving his own.

Daniel Roebuck (Deputy U.S. Marshal Bobby Biggs): It was kind of like Quantum Leap, where you saw a different strata of society everywhere that Janssen touched.

Joe Pantoliano (Deputy U.S. Marshal Cosmo Renfro): It’s the classic Les Misérables story. If I watched it today, it would probably be kind of silly, but David Janssen was a big draw. Everybody loved him.

One big fan was Hollywood producer Arnold Kopelson. In the early Eighties, he began dreaming of a big-screen adaptation.

Stephen Joel Brown (Co-Producer): Arnold was an extraordinarily tenacious producer, a throwback to an earlier time. He spent at least 10 years talking to me about making a Fugitive movie. He really went after it. He was on a quest to get the rights to that show.

In 1986, the rights to the show transferred from Tri-Star Pictures to producer Keith Barish.

Keith Barish (Executive Producer): When I secured the rights, I started watching old tapes of The Fugitive. It was still compelling. At the time, there were not many television shows that had been turned into movies. They did try with Dragnet [in 1987], but that was done as a comedy with Dan Aykroyd and Tom Hanks.

“Dragnet” was a parody of the painfully earnest Sixties police procedural show, and even featured a ridiculous music video where Aykroyd and Hanks rap and dance in a police station. Once Barish and Kopelson joined forces, they started envisioning “The Fugitive” as something far more serious.

Keith Barish: The series held up so well as a story. We just felt it could be a really, really good movie if done right.

Stephen Joel Brown: Arnold spoke with Keith Barish and he was like, “Why don’t we bring this to Warners?” And Warners jumped on it. The biggest challenges was moving it away from the episodic feel and making it feel like a movie.

II – The Screenplay

Several screenwriters worked on “The Fugitive” in the late Eighties and early Nineties, including Walter Hill, best known for his work on “The Warriors,” “48 Hours,” and “The Getaway.” But only two wound up with credit on the finished product: David Twohy and Jeb Stuart. Twohy had first whack at it.

David Twohy: My first produced script was called Warlock. Arnold Kopelson produced it. He and I were like oil and water, always. At a certain point, he fired me even though Warlock was my own project. The studio eventually hired me back. One bitterly cold day on set, which was a 17th-century village in Massachusetts, I went into one of these little period gristmills just to get warm. I was warming my hands on a brazier when Arnold walked in. We started talking and managed to reconcile. He said, “I’m making The Fugitive with Keith Barish. Do you know it?” I go, “Yeah, it’s the innocent man, wrongly accused. It’s Les Misérables, now that I think about it. He’s chased not by Inspector Javert, but Deputy Marshal Gerard. Arnold, you’ve got Les Misérables on your hands!” He goes, “Really?” I go, “Yeah!” He goes, “You want to write it?’ I go, “Yeah, sure.” We hammered out a deal right there in the gristmill.

To prepare, Twohy watched about 60 episodes of the original “Fugitive” series. He wrote a screenplay where Kimble travels across the country while attempting to prove his innocence. And although much of his work didn’t make it onto the screen, it was his idea to turn a simple train derailment, as seen on the Sixties television show, into a violent shootout on a prison bus that crashes and collides with an oncoming locomotive. He also wrote several of the other set pieces that found their way into the movie largely intact, like Kimble visiting a one-armed man in prison, and nearly getting caught by Gerard. He also had the idea of Kimble jumping off a waterfall to escape Gerard, but went way bigger than the shooting script by placing it at Niagara Falls.

David Twohy: My Act Three was always spread across three different Northeastern states, sort of an elaborate multi-state chase. And my bad guy was a coal baron, who was also the father of Kimble’s dead wife.

In Twohy’s screenplay, Kimble eventually learns that the one-armed man worked for the coal mine a decade earlier, and lost his limb in a mine collapse. The murder of Kimble’s wife was an act of revenge. There was also a romantic subplot where Kimble has an affair with his dead wife’s sister while on the lam. From her, he learns that his former father-in-law was a monster that molested both of his daughters as children. It leads to a violent, climactic confrontation between the two men at a coal mine.

David Twohy: I remember Kopelson saying to me, “That’s nothing anymore. It’s almost fashionable to abuse your daughters in the movies now. Everybody does that.” I was like, “Holy shit. Really, Arnold? Really?” So he didn’t like that, and it didn’t fly. (Kopelson died in 2018.)

Twohy was eventually taken off the project and replaced by “Die Hard” screenwriter Jeb Stuart.

Jeb Stuart (Screenwriter): I never had a conversation with David, because the drafts that I got sent from Warner Brothers were all from guys like Larry Gross and Walter Hill. They had taken the story to Mexico and all over the world. And while being on the run worked great for a TV series, it didn’t work great for a feature. I felt like Kimble had to solve a problem and be proactive. To me, that problem was really simple: “I didn’t kill my wife, and nobody believes me.” And the only way you can figure out what actually happened is to go back into the belly of the beast, which, in my telling of the story, was going to be Chicago.

Andrew Davis (Director): One early script I saw was totally ridiculous. I think Walter Hill had developed it. It had Gerard hiring the one-armed man, because Kimble had screwed up on the operating table while performing surgery on his wife.

Jeb Stuart: In all of the drafts that Warners had sent me, the Gerard character was the bad guy. He was the person behind everything. And so he had an incentive to make sure that the one-armed man was never found and that Kimble stayed on the run. I kept saying, “That’s wrong, that’s totally wrong. You need to make this guy be the guy that would never stop hunting. He has to say to himself, ‘Wait a minute, this doesn’t make any sense. Why did he come back to this area?'”

The decision to pin the murders on evil pharmaceutical executives and their hired henchman came after Andrew Davis was hired to direct.

Andrew Davis: I called up my sister, who was a nurse at Cedar Sinai Hospital in L.A., Josie. And I said, “Jo, what could get a doctor in trouble? I got this biggest movie star in the world, the studio’s hot on me this week, and what are we going to do? I got to fix this. What can get a doctor in a lot of trouble?” She called back a couple of days later with some wonderful resident who never got credit and said, “What if there’s a drug protocol?” So my sister and this resident were responsible for the spine of The Fugitive script. We created a company called Devlin MacGregor. My dear producer, Peter MacGregor-Scott, inspired the name Devlin McGregor. And Provasic, I think, came from one of the doctors at the University of Chicago.

David Twohy: I thought the pharmaceutical angle was good since it gave you a bad guy on a different level, but maybe it was too complicated to explain. It required a little more exposition than I would’ve liked. And what I like about The Fugitive is it’s almost all front story. It just goes and goes and goes, and it has two engines. One is that you are being pulled through the story by your chase of the one-armed man, and then you are being pushed from behind as well by Inspector Javert or Deputy Marshal Gerard. And that’s a good structure. I like that a lot. And I like that it was almost all in the present tense, and it didn’t require a lot of elaborate backstory.

Part III – Assembling the Team

Andrew Davis was hired to direct shortly after finishing work on the Steven Seagal film “Under Siege,” which made $156.6 million off a $35 million budget.

Stephen Joel Brown: Under Siege really elevated Andy, and it gave us and the studio the confidence that he could handle a big action movie. I watched it with Arnold. He said, “This guy should direct The Fugitive.”

Joe Pantoliano: In Under Siege, Andy had a guy that couldn’t act in the lead role, and he surrounded him with great actors, like Tommy Lee Jones.

Andrew Davis: I was at the Under Siege afterparty following the premiere, and Arnold Kopelson came in and said to me, “I know your next film.” And I didn’t know Kopelson. I knew he was somehow involved in putting the money together. He was like a broker or a salesman. And so I said, “OK.” And then I got a call Sunday night from the head of Warner Brothers production, Bruce Berman. He said, “Congratulations.” I said, “What?” He said, “Well, Harrison Ford saw Under Siege over the weekend, and he wants you to make The Fugitive.” I said, “OK. Amazing.”

Many A-list actors were discussed for the Kimble role, and Alec Baldwin was briefly attached to it when the Walter Hill script was in development, but they settled on Harrison Ford.

Keith Barish: If you look at the stars at the time, I don’t know who could have pulled it off besides Harrison Ford. It would have felt silly to make Tom Cruise a heart surgeon, and it would have turned it into a Tom Cruise movie. Mel Gibson would have made it feel like Lethal Weapon. I didn’t want to make it a cartoon. I wanted to make it a serious action movie with a serious foundation. Harrison Ford just always felt right.

Cathy Sandrich (Casting Director): Harrison is a thinking man’s action hero. He is immediately credible. You trust him. You believe him. You care about him. Harrison also has such a profound depth of character that just radiates from him. He’s that stoic, silent, dogged hero.

Andrew Davis knew exactly who he wanted for Gerard.

Andrew Davis: We had just finished Under Siege. Tommy Lee Jones was in the movie more than Steven Seagal. I knew he’d be perfect.

Don Brochu (Editor): Steven Seagal was locked in a refrigerator for about a third of that movie. And if you saw it, you know how intense Tommy Lee Jones was in that role. He was the villain, and you’d just feel creepy when he got on the screen because you didn’t know what he was going to do next. Well, he could play a good guy, too, with that same level of intensity.

Andrew Davis: Tommy was wonderful. And it was the second movie I’d done with him after this Cold War thriller, The Package, that I did with him and Gene Hackman. We had this relationship. But initially, Harrison was gun shy about Tommy. He thought he was too powerful, and he was going to take over the movie. And he was right, because he won the Academy Award. But then Harrison afterward said the joy of working on the movie was working with Tommy Lee Jones, even though they only had two scenes together.

For the tragic role of Helen Kimble, they settled on Sela Ward, who was midway through a six-year run of the NBC primetime soap opera “Sisters.“

Cathy Sandrich: We wanted Sela to represent everything that was good and right in his world [prior to the murder]. She was the embodiment of this loving, playful, beautiful wife that completed his life so that you could see how much he lost.

Sela Ward (Helen Kimble): It started with an impromptu meeting on the Warners lot while I was filming Sisters. I was called into a room with Harrison Ford and Andy Davis. We just sat there and talked for a bit. Harrison is so charming. At one point, he turned to one of the producers and raised his eyebrows and grinned. It was him saying, ‘OK, this one has my seal of approval. We can check this box.’ I was so grateful since I had a six-year contract with Sisters, and I’d seen so many people from the show, like George Clooney and Ashley Judd, take off and have these amazing careers. I couldn’t do that since I was one of the sisters, but they gave me a two-week break to fly to Chicago to work on The Fugitive. It was a very big deal to me.

They fleshed out the cast by hiring Richard Jordan as the evil Dr. Charles Nichols, Greek-American character actor Andreas Katsulas as Fredrick “The One-Armed Man” Sykes, a diverse crew of U.S. marshals (more on them later), and Julianne Moore as Dr. Anne Eastman. She only has a couple of tiny scenes, but her name is very prominent in the credits since she nearly had a much larger role.

Jeb Stuart: Warner Brothers sent a mandate to me that said, “We need a female character in this, and we need a love interest for Harrison.” And I said, “You guys, have you been reading any of the script? The whole thing is about a man trying to convince everybody in the audience that he didn’t kill his wife, that he loved his wife, he adored his wife. He would never kill her. Now, you’re going to make me pop him into bed, when he’s on the run, with an actress, just because you need a love interest?” And they said, “Yeah, something like that.”

Andrew Davis: There was a sequence where Kimble met her in the hospital, and somehow he was going to wind up at her apartment and take a shower.

Don Brochu (Editor): It was actually going to be a relationship at one point. Her and Kimble were going to get it on, which was pretty crazy.

Andrew Davis: And about three days into shooting, my dear producer Peter MacGregor-Scott said, “Andy, we can’t do this.” I said, “You’re absolutely right. There’s no way that this guy mourning over the death of his wife can be with another woman in this movie.” And so we called up Kopelson. We said, “Arnold, tell Julianne, we’re cutting those scenes.” She wasn’t very happy about that.

Keith Parrish: I remember us talking with her, and she was so lovely about it because that’s an awful conversation to have with an actor. But she was really gracious about it.

Andrew Davis: It wasn’t like we didn’t like her, that she wasn’t good. It just was going to destroy the movie.

Part IV – Filming on Deadline

The script was nowhere near ready when filming began in the fall of 1992, but Harrison Ford’s window of availability was limited, and the movie was booked in theaters for August 1993. It was, to put it mildly, a difficult situation.

Jeb Stuart: We had a ridiculously short amount of time to make a giant feature.

Keith Parrish: We couldn’t wait around to get the perfect script. And it was a big action movie, and Warner Bros. wanted it for Aug. 6.

Jeb Stuart: Warner, like all studios, had sharp elbows. They were like, “We’ve got a Harrison Ford movie, and you don’t want to compete with us on this date.” Aug. 6 had been carved away for us back in the wintertime. You could not push it. If you miss that deadline, Hollywood starts to talk. “Oh, the Harrison Ford movie has got some problems and they’re working on it.” You really had to hit those deadlines. You’ve got a marketing campaign that’s going full steam. And all those prints need to hit those theaters at that particular time. So, that was that.

In a break from decades of Hollywood tradition, they shot the movie entirely in sequence. It started with the train crash sequence near Cherokee, North Carolina, moved to the Cheoah Dam in Robbinsville, North Carolina, for the dam sequence, and wound up in Chicago for the rest of it.

Cathy Sandrich: I think that having a deadline added a higher level of enthusiasm and real electricity on set.

To create a sense of authenticity, they created very few actual sets and relied almost entirely on real locations, like Cook County Hospital, Chicago City Hall, and the Chicago Hilton.

Andrew Davis: One of the only sets was the apartment where the murder took place, and that was shot at a real apartment. We came up with that after going to dinner with Harrison and my assistant, Teresa Tucker-Davies. We bumped into a doctor who was an OB/GYN who had this gorgeous wife. Harrison said, “I’m going to start modeling my character around this guy, even his beard.” We went back to his house. It was this modern house with art everywhere and a little pool in the back. It was in Old Town, right in Chicago. They literally took that floor plan, and we built that apartment for Harrison.

Sela Ward: I remember there was a big debate about whether he should have that beard or not. I don’t think the studio liked that beard. I remember him being very attached to it, and it was just fascinating, all the intricacies of creating a character.

If “The Fugitive” was shot today, they’d use a green screen and CGI to create the dramatic train/bus crash at the beginning. Back then, they had to rely on practical effects. The sequence cost roughly a million dollars and was only able to run a single time.

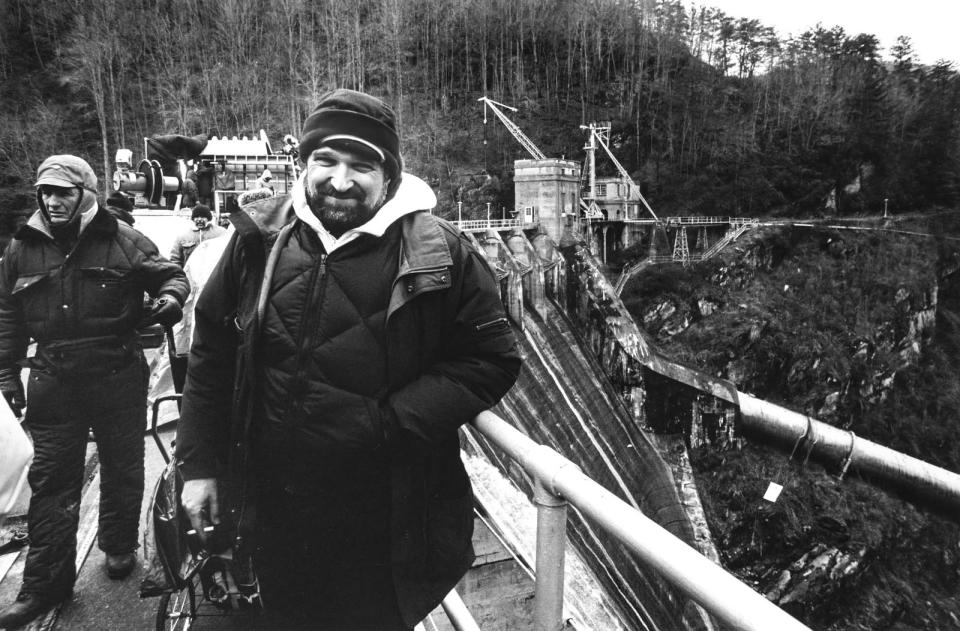

Andrew Davis: It was an engineering piece. Roy Arbogast, who was the special-effects coordinator, basically engineered it. We found a piece of the track that was abandoned in Carolina and some carcasses of old engines and cars with all the guts taken out of it. Roy engineered it so that the train would ditch the engine.

Stephen Joel Brown: This is an example of doing things practically where it just works so well. It’s heart-throbbing and feels so realistic. It’s great, but you have to have such a great, well-coordinated and fine-oiled machine to get it done. That scene has been talked about over and over again, and we just had one opportunity to do it. It wasn’t like, “Oh, if it doesn’t work, we’ll fix it. We could do it again.” I mean, that was it. It was like you get it or you don’t.

Andrew Davis: If you notice, Harrison’s limping in a lot of this. He hurt himself in North Carolina when we were doing the trains. And through the whole movie, he was on medications, and he really was hurting.

That obviously wasn’t part of the plan, but it made him look even more realistic as the character. It was especially helpful in the next major scene, where he’s being pursued by Gerard and his team through a tunnel that leads to the Cheoah Dam.

Andrew Davis: We shot the real water in the dam with Harrison standing above, tied to a wire. Then later on, we came back to Chicago, took over an old steel-fabricating place, and we built this long set. It had all the components of the dam and water dripping, and we could light it. And so those were done in two different pieces.

The famous swan-dive scene came right from Twohy’s original draft.

David Twohy: The chase through the storm drains was my homage to the sewer sequence in Les Misérables. And his jump was just a logical ascension of the chase. I said to myself, “Well, all this water’s got to go fuckin’ somewhere, and I’ve got to have him escape in a logical way to allow him to pursue his quest of the one-armed man.” So I said, “What’s the most dramatic way possible for him to escape? That’s the most dramatic way possible.”

In perhaps the most famous scene in the movie, Kimble points a gun at Gerard and says, “I didn’t kill my wife.” Gerard responds, “I don’t care.”

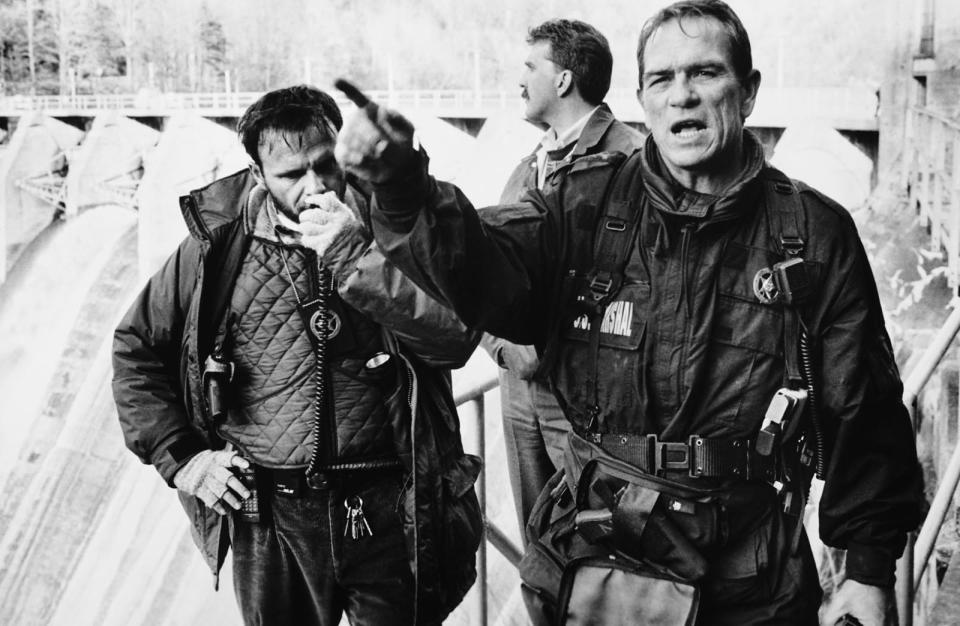

Tommy Lee Jones: The deputy marshal I had been talking to emphasized a couple of things. One of them was that the innocence or guilt of the people he was trying to serve warrants on was not really important to the process. He didn’t care if the people he was chasing were guilty or not. It was his job to catch them. It was somebody else’s job to decide whether they were guilty. And the thrill of the chase was something the fellow really enjoyed.

Jeb Stuart: I was on set that day. Tommy did not want to say “I don’t care.” But he needed to tell the audience he does not care if the guy’s innocent or guilty. It was freezing cold. The water’s running through. Harrison had been such a trooper. He’s standing there in this opening, which has a jump of about four feet, to a mattress. We’re all freezing. And Tommy keeps saying, “No, I don’t like that line. It doesn’t work.” And we had, “I don’t care” in the script, but he kept trying others. And so after a while I just said, “Why don’t you just try, ‘I don’t care?'” And once he did it, Andy Davis said, “That’s it. Wrap.”

By complete coincidence, the Saint Patrick’s Day Parade was taking place in Chicago the same week they shot the scene where Kimble narrowly escapes Gerard at Chicago’s City Hall.

Andrew Davis: I couldn’t let Tommy give up. And so I said, “Let’s have him run into the parade and get lost in it.” The city backed us to the hilt. I think Harrison grabbed that hat [from the garbage can] on his own. And we had Steve St. John, this incredible steadicam operator, follow Tommy and Harrison through the parade. It was a real parade. We didn’t restage anything.

The parade sequence was a great ad-hoc addition to the story, but they still didn’t have any idea how the movie was going to actually end at this point. Weeks and weeks ticked by without a clear answer.

Jeb Stuart: I had all the strands in my head, but I couldn’t get them down on paper. Everything was screwed up. We finally had a production meeting set for very early on a Saturday morning. And I remember on that Friday night, early Saturday morning, I worked on it, worked on it, worked on it — finally, at one or two in the morning, I said, “I’m going to fall on the sword and say I don’t have it.” And it’ll probably shut the movie down because we don’t have the last 20 pages of the script.

Joe Pantoliano: We were all staying at the Four Seasons in Chicago, and they had this great spa. And I remember one night in the pool, they were still figuring out who the bad guy was. I remember saying, “That ending, Jeb, has got to be really dramatic. What if the bad guy jumped off the roof and landed through a skylight?” ‘Cause there’s a skylight overhead that looked into the pool. So during the day, it gets sunlight from this big skylight. I said, “Look at that skylight. Wouldn’t it be cool if the guy jumped off and he went through the skylight and he landed in the water and died?”

Jeb Stuart: It was now 2 a.m, hours before the meeting, and I don’t know how the whole mystery wraps up. I turned off the light at about two in the morning, and at 2:05 I turned it back on and it was all clear. It’s like Faulkner said, it was a gift of the subconscious. I sat down and wrote the end of the movie, and everybody came in the next morning and read it. And everybody said, “Well, this is great. What took so long? Why didn’t you give us this a month ago? This is so simple.”

His idea involved taking the action to a hotel where Dr. Nichols was giving a presentation to a large crowd in a ballroom. And, yes, it involves Nichols eventually falling through a skylight.

Jeb Stuart: Having Nichols speak at a conference allowed Harrison to have that moment to turn around and tell those people in the audience what they’d been missing. There are just an enormous number of threads that had to come together with tissue samples and everything else. And remember, the audience is only one part of that equation. The only person that mattered to me, who got it, is Gerard. If Gerard doesn’t get it, or if you, as the audience member, get it before Gerard, he would never win the Oscar. You’ve got to make it so that a-ha moment is tying together at the right time.

They’d filmed many scenes up to this point with Richard Jordan as Dr. Charles Nichols. But Jordan was diagnosed with a fatal brain tumor before they could film the climax at the hotel. They’d need to quickly hire a new actor, reshoot the prior scenes with Nichols, and prep the big fight at the end. (Jordan died weeks after the movie hit theaters.)

Jeroen Krabbé (Dr. Charles Nichols): I was called by my agent in L.A. in the middle of the night. I was in Holland. I thought, “Oh, my God, it must be something with the kids,” because it was such an odd time to get a call. She said, “They need you on a plane to Chicago first thing tomorrow morning.” When I got there, I didn’t even have to go through customs. They rushed me in a stretch limo to the set. I was thrown into wardrobe and makeup. And there I was. I didn’t know anything. And then Andrew Davis came in and he said, “Oh, welcome. So happy you’re saving the movie. First, I’ll introduce you to Harrison Ford.” And there was Harrison Ford, I was in shock because I knew Harrison Ford from the movies — I’d never seen him in real life. I said, “Listen, I was in the middle of the night being called up by my agent last night, and now I’m here, so I don’t know what to do.” And he put his arm around me, and he said to me, “I’m going to help you, buddy. Don’t worry.”

If you look very carefully at Kimble’s beard in the scenes with Nichols before the hotel scene, it looks just a little bit off.

Jeroen Krabbé: Tommy Lee Jones had to do all his scenes with my character again. Harrison Ford had to put on a fake beard. It took hours and hours in makeup. I thought it was so sad he had to do that.

The entire movie builds to a fight across several parts of the Chicago Hilton between the two actors. After three “Stars Wars” and three “Indiana Jones” movies, Ford was used to sequences like this. Krabbé was not.

Jeroen Krabbé: The whole fight in the Hilton Hotel was staged by stunt guys, of course, but it was also staged by Harrison, because he is incredible at fighting. He’s so good. He talked me through it and he said, “Don’t worry. Do just what you want to do and eventually throw me to the wall.” It all went very well. I did about maybe 95 percent of the whole fight myself. The only thing I couldn’t do, because I wasn’t allowed by insurance, was to fall down the stairs outside. That was a stunt double.

In a final act of amazing fortune, fireworks shot off in the distance just as they were filming the last shots of the movie.

Andrew Davis: They just happened when we were shooting at the top of the Hilton. I said, “Start rolling! Shoot them!” It was a perfect ending for the movie.

Throughout all of the chaos and unexpected setbacks, few people thought they were making something timeless.

Joe Pantoliano: We were lucky. Look, I’d be lying to you if I didn’t tell you that I think everybody thought this was going to be a real dud, except for Andy Davis.

Andrew Davis: Tommy thought this was going to end his career.

Daniel Roebuck: Harrison Ford said in front of me when we were in the water, so I can attest that he said it. He goes, “Oh, man, this is going to be my Hudson Hawk.”

Tommy Lee Jones: I remember being in the giant basement of that hotel, surrounded by hanging bags of laundry. I was standing there speaking out to Harrison’s character. And there was nothing there except big bags of laundry. And I remember thinking in the back of my mind, “I’ll never work again. This is never going to work. And the best thing I can do is be as clear, concise, and coherent as possible, deliver these lines as cleanly and dutifully as possible, and maybe I’ll get another job one day, somewhere down the line.”

Jeb Stuart: And I have to tell you — you may not hear this from other people — but I remember laughing about it with Harrison a lot. We didn’t really think we were going to ever work again after this movie.

Part V – Big-Budget Improv

The topic that comes up the most when speaking with the cast and crew of “The Fugitive” is the crazy amount of on-the-fly script changes that occurred throughout the shoot. Accounts differ slightly, but they all agree that a large percent of the dialogue in the finished version did not come from the script. For a big-budget action movie, this is highly unusual.

Andrew Davis: There was never a finalized screenplay. I knew every day what the scene had to accomplish. I knew the storylines. For example, the scene where Gerard is listening to the tape [of Kimble’s phone call] and they’re hearing the bell ring on the L Train, all that was completely written that day on the set, by myself and the cast. So the point is that we knew what the spine had to be, but the actual rhythms and the words were done by myself and the actors.

David Twohy: I’ve seen a lot of talk about how the actors improvised all the dialogue in the movie, which is a slap in the face a bit to me, and especially to probably Jeb who is on the set, theoretically there to do that for them.

Andrew Davis: I’m not putting down anybody. But it just kills me to read “This wonderfully crafted script by David.…” And Jeb Stuart’s a sweetheart. He was there with Kopelson and the executives in the hotel.

Don Brochu: It was being written right up until the end. The writer [Jeb Stuart] was up at the Four Seasons, locked in there and sliding pages underneath the door.

Andrew Davis: We’d be writing this dialogue and trying to figure out this stuff, and he’d hand it to me and say, “OK, fine.” Then we go to set and use some of the words he gave us. Then we’d redo it.

Tommy Lee Jones: The script was in flux. On the days that I worked, we had a lot of meetings before shooting to look at the problems we had with the script. We’d discuss how to solve them. We did a lot of preparation based on the script, and we did a lot of last-minute work to make sure everything cohered.

Tom Wood: It was definitely being written by committee. Harrison Ford had a lot of pull. And I’m not saying that that’s a bad thing.

Stephen Joel Brown: There was a lot improv. If we started this movie under normal circumstances, we could have had something close to a shooting script. But Harrison Ford had his schedule and the studio wanted to get this thing moving. And every time you make one change, it’s like dominoes.

Daniel Roebuck: We all rewrote the script when we were on the set. “Rewrote” is maybe not the correct term, because it’s a great script. We improvised within the character that they had created. That’s what we did.

Tommy Lee Jones: My recollection is that there’s very little improvisation. Somebody might say, “Excuse me,” at some point and just try to drop that in. And then they call that improvisation. Of course, it’s not. The dialogue could have been freshly written that morning in somebody’s trailer, but that’s not improvisation.

Sela Ward: Harrison didn’t like the script. Early on, I had a scene where I was driving home with him after a party. Harrison turns to me and says, “OK, what are we going to say?” And I went, “You don’t like the scene like it’s written?” And he goes, “No, no. So what are we going to say?” You’ve got to remember, when he did Star Wars, I was 20. He was such a hearthrob for me. I was still at the University of Alabama. And here I am in this car and I’ve got this job and I’m playing his wife. And so, I mean, you can imagine how intimidating that was. I didn’t grow up doing improv in this business. On Sisters, I wasn’t allowed to change a word. I was just terrified. I think I turned to him and said something like, “You look great in a tux.”

Tom Wood: There’s a scene where we’re all sitting on the side of the train-wreck demolition site. We were questioning the dialogue and saying, “Let’s spark this up a bit.” I’m not the fastest thinker and was caught a little off-guard. Tommy turns to me [with the cameras rolling] and says, “What are you doing?” I go, “I’m thinking.” He goes, “How about you think me up a cup of coffee and a chocolate donut with some of those little sprinkles on top?” Later on, at the hotel scene, he says to me, “Don’t let them give you shit about your ponytail.” That was completely improv’d.

Daniel Roebuck: The quote that everyone brings up to me is “If they can dye the river green today, why can’t they dye it blue the other 364 days of the year?” That was an improv. And that was because we had that huge walk that we had to cover. And I remember asking Andy, “Did you shoot the green river?” He goes, “Yeah, we’re cutting it in.” And that’s how it came to be.

Joe Pantoliano: When we first get into the storm drain, I go, “Goddammit, I just got these shoes.” All the lines down there were improvised.

L. Scott Caldwell: There were a couple of moments where I had a problem with a costume because my shoes didn’t fit. And every place that we were working outside of the ground was not level, and I stumbled because my shoes were too big. In my first scene, Joey says something like, “I told you not to wear those heels.” And then Tommy Lee says, “No. No. No. You just need new boots,” or whatever. With those kind of things, Tommy would take a real moment that was actually happening in real time and feed it into what we were shooting. He was very good at that, very quick in that regard.

Cathy Sandrich: There’s still this moment where Harrison goes into the tunnel and Tommy says, “We’ve got a gopher.” Tommy improv’d that.

Joe Pantoliano: We met with real U.S. marshals before filming. One of them was talking about a guy that jumped off a roof and said, “He did a Peter Pan right off that roof.” Tommy and I had a battle over who would say that line. Tommy, of course, won.

L. Scott Caldwell: There’s a line where Joe says to me, “What’s a cardiovascular surgeon?” And I say, “Somebody that makes more money than you.” That was just me saying that.

Of course, not every line was the result of improv.

David Twohy: I’ve seen Tommy Lee Jones talking about how he came up with the line “Every doghouse henhouse, penthouse, cathouse in the area, hard-target search.” And I thought to myself, “No, wrong. That’s in my script.” By the way, I just made up “hard-target search.” I have no idea what that means.

Andy Davis: One of the most famous lines in the movie was written by the copy people who were writing the trailer. “Every doghouse, outhouse.…” That was written by marketing people.

Twohy has a pretty strong case that he came up with much of the monologue himself. Here’s the scene as written in his February 1992 script:

“Our fugitive’s been on the run for 90 minutes. Average foot speed over uneven ground — eight miles an hour, giving us a radius of 12. We’ll do a hard-target search of any residence, gas station, farmhouse, henhouse, doghouse, and outhouse in that area. Check points go up at 15 miles, but stay alive to reports of stolen vehicles or abductions.…”

Here is what wound up on film:

“All right, listen up, ladies and gentlemen, our fugitive has been on the run for 90 minutes. Average foot speed over uneven ground, barring injuries, is four miles per hour. That gives us a radius of six miles. What I want from each and every one of you is a hard-target search of every gas station, residence, warehouse, farmhouse, henhouse, outhouse and doghouse in that area. Checkpoints go up at 15 miles. Your fugitive’s name is Dr. Richard Kimble. Go get him.”

Joe Pantoliano: That whole scene was a PR thing since they were going to send it to the distributors. And Tommy, if you look at it closely, was not happy doing it. He rewrote it and made it better. But it was like he had disdain for having to say those words. He hates being the vessel to the exposition.

Daniel Roebuck: Tommy did that monologue twice. One was for the movie and the other for the trailer. They took us out of the shot for one, so it was just him talking to extras. And when you watch the movie, you’ll see they cut between the monologue he did for the trailer, which didn’t include us, and the monologue in the movie, which did include us. And it’s odd — you’ll note that people aren’t where they’re supposed to be when they intercut. That’s a little secret. I shouldn’t tell you that.

Tommy Lee Jones: I think I did that on one of the very first days of shooting. And that long speech was given to me by the public-relations department. He said, “You need to shoot this afternoon so we can have it for public-relations purposes.” And I said, “There’s a lot about this movie we don’t know. What am I going to do with this speech?” They said, “OK, just do it, and it’ll be fine.” So I just did it.

Andrew Davis: Harrison and Tommy and I basically wrote the dialogue for this movie. I could be wrong, there could have been some key moments that Jeb had a lot to do with, and he was great to work with.

Tom Wood: None of this is meant to slight Jeb. He was being handed sort of recycled ideas from the studio because of their fear. And I’m sure he was doing everything he could. But I write too, and I know that your first draft is not your best. And if you’re being asked to push out dialogue to film tomorrow, and the actors or director decide to do some improv’ing and make some changes, I don’t think there’s any shame in that.

Jeb Stuart: For me, an improv that doesn’t affect the story is OK. There’s always a margin where you have to do it, especially when you’re trying to get a little humor into a scene. I don’t have any problem with that. It only becomes a problem when you have an actor that says “I have an idea for this particular scene” and you have a director that doesn’t know where the scene is going. Once you shoot it, you’re locked in.… But movies are an amalgam. They’re a tremendous collaborative effort.

Part VI – Gerard and His Marshals

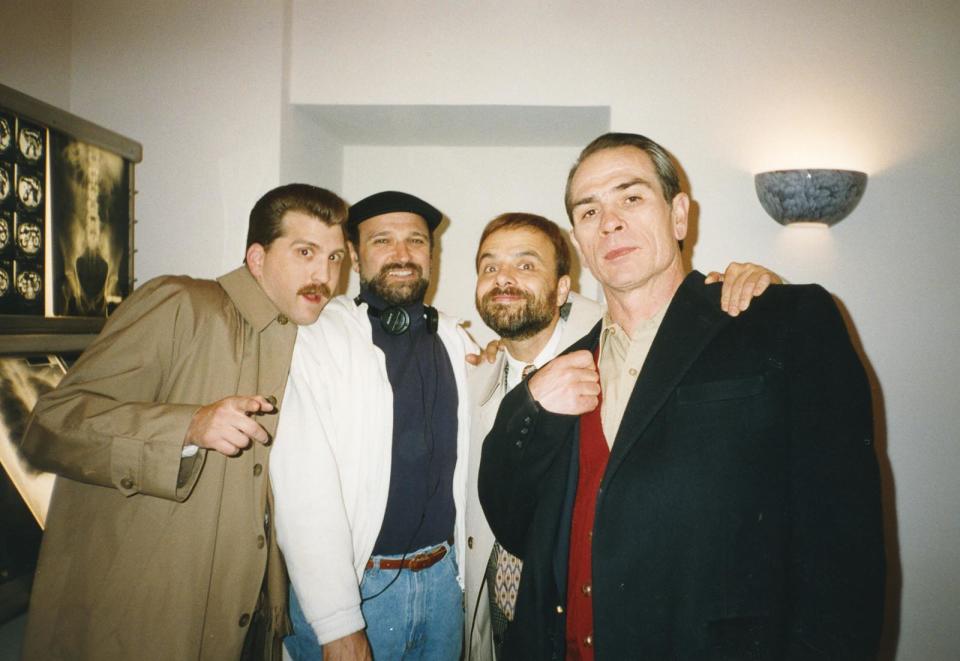

In several drafts of “The Fugitive” script, Gerard’s team of marshals were minor players without any real individual characteristics. That changed once they cast Joe Pantoliano, Daniel Roebuck, Tom Wood, L. Scott Caldwell, and the late Johnny Lee Davenport.

Andrew Davis: An executive at Warner Brothers said to me, “What do you need all these people around Gerard for? Just give him a sidekick.” And I said, “No. You need to have this palette of people of color, of different sexes, of ages … the guy with the ponytail and everything like that, that Tommy could play off of and he become the papa to this group of people.”

Joe Pantoliano: These marshals were originally cutout characters. They were wearing raincoats. They didn’t even have first names. They were all last names.

L. Scott Caldwell: Joey was smart enough to say, “Scotty, call me Cosmo on camera.” He would have everybody call him Cosmo. He created that. He was smart enough to be able to get you to help him do that kind of thing. He was very mischievous in that way.

Cathy Sandrich: One of the things that I loved about both Andy and Arnold is that they were very cognizant of, when they could, putting women in positions of power, and non-white women.

L. Scott Caldwell: On one of the early scripts, there was a scene in there where I go into the men’s room. They’re in there pissing, and I’m trying to show Tommy something that I found. And the guy says, “Lady, would you get out?” and I said, “Fuck you,” and I keep going with what I’m doing. So, they were going to play her as that kind of person, that she barges into a man’s world, no matter what.

Tom Wood: Joe Pantoliano was instrumental in helping to develop that camaraderie that we had. Once we were all sort of cast, he invited us all out for a meal. He’s one of the best people out there. And so we all showed up at a restaurant and just hung out, a bunch of strangers. But really that sort of broke the ice.

Daniel Roebuck: Tommy Lee Jones, who I didn’t know at all, he was going to have an enormous impact on the storytelling, because of his very smart attention to detail. And he really wanted us as a troop. And he was certainly our troop leader. He wanted us to all have distinct, unique personalities.

Tommy Lee Jones: The company had an adviser who was a young, very enthusiastic deputy marshal. And I spent a good deal of time with him talking about his work, how he felt about it from day to day. And my rather marvelous discovery was how much fun this guy had doing his work, how much he loved it. And I thought that was important. I thought that’d be important for Gerard and his crew to be understood as really enjoying their work and being good at it.

L. Scott Caldwell: At one point, I was looking at how the thing was going down, and I was starting to notice a pattern. And I say, “Well, how is it that Joey is always in the frame? He’s always in the right place.” And I noticed. I said, “Oh, he’s Velcro’d next to Tommy.”

Daniel Roebuck: With the power of a Jaguar, he would always get himself next to Tommy, and then he would start talking business behind Tommy, so that he would force coverage on himself.

Joe Pantoliano: There was only one wireless mic, so I was always fighting for the wireless mic so I could be heard. I came to the conclusion that if I could insert myself to Tommy Lee Jones, that they would be forced to give me the mic and I’d be in the movie more.

Daniel Roebuck: I was a little annoyed at Joey because we’d do a scene with two people talking, and Joey would somehow wind up behind you making a sandwich even though he was nowhere near there before. I’d be like, “Joey, you can’t be here and there.” He’d go, “No, no. I crossed, I crossed. You don’t remember, I made a sandwich while I was talking.…” At the time, I was aggravated. I resented him. But, dude, you can’t not love him. He is so nutty. I fell in love with him.

L. Scott Caldwell: There were a couple of occasions where Tommy would give me a nudge, or call me, or make sure I moved to a certain spot. In some ways, he was our little director. I mean, Andy was doing the big thing, and Tommy was choreographing in some ways what it looked like, how he needed people to adjust themselves around him.

Tommy Lee Jones: Before we started shooting, I spoke to Joey Pantoliano, whom I know, and said, “Joe, we got to have a lot of fun on this thing. If we’re going to do this movie, the best service we can do is to enjoy it. So let’s be sure that we’re having fun every minute. If we’re not having fun, let’s stop and figure out why and then make some decisions that are fun.” And I think that served the movie pretty well. You could see that those people were used to working together, enjoyed working together, and had their resentments and their jokes, just like human beings. And I thought that served the narrative pretty well, that we had that spirit among the U.S. marshals and the deputies, that they were, well, having fun.

Tom Wood: I don’t think Tommy ever stepped on Andy’s toes, but I do think he definitely made himself vulnerable to us by really investing his ideas and perspectives and encouragement among us.

Daniel Roebuck: Tommy Lee Jones, respectfully, is a Rhode Scholar. In any room he’s standing in, he’s the smartest man. You could bring in Stephen Hawkings and Stephen Hawkings would be like, “Whatever, that’s fine with me.” I don’t know if I ever worked with an actor like him, who grabbed the ball and forced it to run where he wanted it to run. I always say these things with great respect. The star of the movie obviously was Harrison Ford. None of this would’ve happened if it hadn’t had the blessing of Harrison Ford, and the guidance of Andy Davis.

Any reference to their lives outside of their work was eliminated from the story.

L. Scott Caldwell: At one point, there was an idea that I was Gerard’s girlfriend. There was going to be a scene where the camera pulls back and he’s talking to somebody and you don’t know who it is. The camera pulls back and it’s me. And they killed all that.

During the Hilton laundry-room shootout at the end of the movie, the story called for Pantoliano to get rammed in the head by a giant steel beam.

Andrew Davis: He gets knocked out. And Joey was so funny because he’s such a sharpie. He said, “Andy, I got to live. You can’t kill me.” Harrison’s like, “There’s no way a beam like that would hit him and he wouldn’t be dead.”

Tom Wood: They wanted to kill off Joe Pantoliano, and he had some very persuasive arguments about that, about not doing that.

Joe Pantoliano: I go running into Andy’s trailer. I go, “Andy, what the fuck? You can’t kill me.” He goes, “Why?” I said, “What if there’s a sequel?” He says, “All right, we won’t kill you. We won’t kill you.” We shot it before CGI. I was thinking, “I’m going to make it so they can’t make me dead.” And so I just started moaning and making lots of noise on the ground. Andy says, “Cut,” and all of a sudden I see these pair of blue jeans walk up to me, and I look up the leg like a closeup, and it reveals Harrison Ford staring down at me. He’s shaking his head. And I go, “What?” And he goes, “You should be dead.” I said, “What if there’s a sequel, Harrison?” He laughed, and then he looked down at me and he said, “Listen, there’s not going to be any sequel because I won’t be in it.” And I said, “Well, fuck you. Who needs you? We’ll just chase another 20-million-dollar asshole through the woods!” And he was on the floor laughing.

Daniel Roebuck: I remember Joey screaming, “There better be a shot of me alive at the end of the movie!” So they put that shot of him on the stretcher into the movie.

Another difficult negotiation took place when Jones balked at a scene where he fired his gun in public while Kimble ran out of City Hall into the parade.

Andrew Davis: Tommy said, “I would never be using my gun in a public place like this. I would never endanger the lives of civilians.” And hopelessly the producer saying, “No, it’s a movie.” And Harrison’s going, “You got to do it.” And I was caught between my actor who had an ethical point of view about it, and making the movie.

Jeb Stuart: I got this call at the Four Seasons, where I was working, and they said, “You need to come talk to Tommy. He won’t come out of his trailer. He has a problem with the script.” We’re editing the movie as we go. I’m spending a good part of my day shuttling back and forth between editors, and the script that I’m trying to write the ending to, and I’m also getting to the set when there’s a problem. And I didn’t have the patience I have today.

Tommy Lee Jones: I didn’t think any law officer would start firing off rounds from a 45 into a crowd of people. I didn’t think a U.S. marshal would do that.

Jeb Stuart: I said, “I’m just going to tell you what the audience is seeing, because we’re cutting this right now. Less than five minutes ago, you just shot an African American man at point-blank range, and yet this rich, white doctor, you’re not even going to pull your gun out? How does that work? What are the optics of that?” And then, in my impatience, I just left the room, and I got in the cab, and I went back to the Four Seasons. Arnold Kopelson called me later that day. I said, “Did he not pull the gun out?” And he said, “Oh, he pulled the gun out. He shot and shot and shot and shot and shot. They didn’t have enough [fake bullets] to do it.”

Keith Barrish: I don’t mind saying Tommy was a very bizarre guy. The cast and crew ate together, and Tommy Lee Jones would be at another table by himself eating lunch and dinner. He didn’t talk to anybody.

L. Scott Caldwell: Tommy Lee was very private. He was never in the same makeup trailer or anything like that. He had a separate makeup trailer, and he wouldn’t fraternize until he was actually on the set. But when he was on the set, he was the one that made it possible for us to feel like a family, because he was the one that was generating that energy. I would give him 100 percent credit for being the fire starter for whatever chemistry we had.

Part VII – The Frantic Race to Finish

They had just eight weeks to edit the movie after filming wrapped.

Andrew Davis: A typical edit is six months. And so there were like six editing rooms, and I would go from one room to the next. Editors would trade off sequences. But basically, Dov Hoenig and Dennis Virkler, and Don Brochu, were the main editors of that movie. And they all contributed wonderful things to each other’s versions.

Stephen Joel Brown: Doing it this quickly was insane. We’re talking about film here, and Andy Davis shoots a lot. But we had an extraordinary editorial team.

Don Brochu: When we left Chicago, the entire company hooked up at Warner Hollywood, which is a small studio lot in the middle of Hollywood on Santa Monica and Formosa Street. It has a ton of history. Howard Hughes used to work out of there. And basically, they sequestered us like a jury. We were there six days a week, probably 12 to 18 hours a day. There were six editors, 10 assistants, and six production assistants. And they wouldn’t let us leave the lot. We’d come in for breakfast, they’d give us lunch and dinner before we left. And that’s how we got it done. We just worked constantly.

Stephen Joel Brown: James Newton Howard created an incredible score under a lot of pressure.

Don Brochu: It’s a killer, killer, killer score.

Andrew Davis: It has an Aaron Copeland quality to it. He had the idea of adding jazz, and adding Wayne Shorter to it. It was just brilliant. It was the temp score that everyone used for 10 years afterwards in all their movies.

The first cut was three hours and 10 minutes. That’s just four minutes shorter than “Titanic.” Big cuts were needed.

Don Brochu: In that first cut, the opening of the movie was a half an hour before Kimble became a fugitive. It was written as a day in the life of Kimble that just went on forever. He goes to a fashion show, he’s on the way home from a fashion show, he gets called into the hospital to do emergency surgery. And then on the way home, he comes into the house and finds that there’s somebody in the house. There was a trial sequence, went on forever. Our biggest concern is that this guy’s got to get on the run. The name of the movie’s The Fugitive, and the guy’s not running for 30 minutes.

Dennis Virkler (who died in 2022) came up with a brilliant way to solve this problem.

Don Brochu: Dennis took the murder scene and made it into a flashback during the main title. That helped pace the movie tremendously. The person that actually took the biggest hit was Sela Ward. She’s in the beginning of the film and most of her stuff was cut down to quick flashbacks.

Davis didn’t originally love the idea.

Don Brochu: But as we got closer and closer to trying to get this thing on the screen, we just knew that you couldn’t go 30 minutes of setting this thing up without Kimble becoming the fugitive. Andy finally came around and then of course he had to put his moniker on it. He got into it with Dennis, and they started working on it pretty intently. And what they came up with is a pretty striking opening. It’s nuts. It’s a brutal, gruesome scene. The one-armed man takes an orb off the thing and just crushes Kimble’s wife’s skull with it. And it was pretty visceral stuff, so we used black and white to sort of take you out of it. And to do it in flashback and do it in bits and pieces like that, you still get the intensity and you still get the visceral-ness of it, but we don’t have to linger long.

Sela Ward: Initially, I thought, “Oh, man, OK, am I going to be in there at all?” But in watching it, I realized that I probably ended up with more screen time in flashback. These kind of movies are made in the editing room.

Part VIII – The Opening, the Oscars

As soon as the final cut started to come together, everyone realized the doubters were wrong. They’d created something incredible.

Andrew Davis: The first time I showed it to Harrison, he was sitting next to me. He had all these trepidations beforehand. We get to the scene where he breaks down and cries [during the police interrogation], and he leaned over and gave me a kiss. He realized you were going to be so empathetic and invested in this guy. Then we showed the picture to the studio. They went, “Don’t fuckin’ touch it! Don’t change a thing.” But we made about 1,800 changes after that.

Don Brochu: When the train wreck hit during a test screening, there was a buzz in the audience for over two minutes. People were just freaking out. After that, the studio totally left Andy alone.

Jeb Stuart: I took my family on a vacation to Europe after the shoot ended, and I was over in Italy someplace and I got a call from L.A. Andy and Harrison were both on the call. Harrison said, “I think we’re going to work again.”

Stephen Joel Brown: Aug. 6 proved to be a wonderful date. It was late in the summer, but it worked. The marketing by Warners was second to none. We had a royal premiere in London [that Princess Diana attended]. We took it to the Venice Film Festival. Harrison’s face was all over Paris in a giant “Wanted” ad. It was quite a ride.

The film grossed $23,758,855 in its first weekend, crushing “Rising Sun,” “In the Line of Fire,” “Free Willy,” and everything else in its path. It stayed at Number One for six weeks until “Striking Distance” knocked it down a peg. It ultimately grossed $183,875,760 domestically. “Jurassic Park” and “Mrs. Doubtfire” were the only movies to make more the entire year. And when Academy Awards nominations came out early the next year, they were up for seven awards, including Best Picture and Best Supporting Actor for Tommy Lee Jones.

Andrew Davis: We got killed by Schindler’s List. You can’t fight the Jews, and I am one. But I didn’t get nominated [for best director], which was very hurtful. And Harrison didn’t get nominated [for best actor], which was unfair. But the sweetest thing happened. Robert Altman was nominated for Shortcuts, which wasn’t a very good movie. He wrote in the trades, “The only reason they’re giving me this nomination is because I’m an old man. Andy Davis should have gotten the nomination.”

When Pantoliano saw that Jones was up for an Oscar, his mind went back to a moment during the shoot.

Joe Pantoliano: We were headed to Chicago from Cherokee. Tommy’s like, “Hey, Joey, we’re going to have fun in Chicago. Do you like Chinese food?” “Yeah.” “We’ll eat a lot of Chinese food, and you like Italian food?” “Oh, hell yeah.” “Yeah, well, we’re going to eat a lot of Italian food because we’re going to have fun. We don’t have to worry about this script ’cause let’s face it, nobody’s going to win an Academy Award on this one.”

Just about a year later, Jones was walking up to the podium at the Oscars to accept his Best Supporting Actor award for “The Fugitive.” His head was shaved because he was in the midst of filming “Cobb.” “My thanks to the Academy for the very finest, greatest award that any actor can ever receive,” he said. “The only thing a man can say at a time like this is I am not really bald.”

Tommy Lee Jones: I was kind of overwhelmed. I didn’t really know what to do except show up and say “Thank you.” But I was surprised that I had a career left after talking to those laundry bags.

Part IX – The Sequel You Barely Remember

When a film hits that big, the studio inevitably starts thinking about a sequel. Not easy in this case. Not only was Ford completely disinterested, but there was no plausible way to make Kimble a fugitive for a second time. The only possible move was to have Gerard and his team of U.S. marshals chase another man on the run. It took several years of plotting, but “U.S. Marshals” hit theaters on March 6, 1998. It reunited Jones with Pantoliano, Roebuck, Wood, and Davenport. Caldwell was asked to return as well, but it conflicted with her commitment to the Neil Simon Broadway play “Proposals.” Davis was also busy directing the Michael Douglas-Gwenyth Paltrow film “A Perfect Murder.” He was replaced by Stuart Baird. Wesley Snipes essentially took on Ford’s role as the fugitive. Robert Downey Jr. was added to the team as an additional marshall that served under Gerard.

Keith Barish: U.S. Marshals was a terrible movie. I read the script and I said, “OK, my name’s on it, but I don’t want to do this.” It was a retread. But what’s good about it is that Robert Downey Jr. had his comeback. Prior to that, he was unbankable. He was untouchable because of his drug addiction. No one wanted to take him, but this was a small enough part that he could have been cut out if there was trouble. I was glad that it was his comeback vehicle. You don’t get that often in Hollywood.

Not everyone was thrilled to see Downey become a part of the marshal family.

Tom Wood: I just felt like what our team had brought to that first film was completely usurped by another actor coming in.

Daniel Roebuck: I think the story’s much too convoluted.

Tom Wood: I’d never done a sequel before, so maybe if I’d had more experience, I would’ve been more accepting of the sort of laissez-faire, doing-it-for-the paycheck energy around set.

Tommy Lee Jones: The thing that drove The Fugitive was that we weren’t chasing just a normal doctor. Whatever we were doing, we were chasing Harrison Ford, and I think he was the engine of the movie. With U.S. Marshals, we had a different director, had a different approach, and it just wasn’t … the movie wasn’t as good as The Fugitive.

“U.S. Marshals” grossed a respectable $102.4 million on a $45 million budget. On opening weekend, it went up against the Coen brothers’ eagerly-awaited follow-up to “Fargo,” “The Big Lebowski,” which centers around a bowler with a love for marijuana that gets wrapped up in a convoluted kidnapping scheme. Three times as many moviegoers saw “U.S. Marshals” as that other movie, which totally tanked. All these years later, however, you won’t find many people fixing up a white Russian, firing up a joint, and watching “U.S. Marshals” for the 600th time. You certainly won’t find anyone dressing up like “U.S. Marshals” characters at fan conventions. Most people barely even remember that it exists.

Joe Pantoliano: We had a ball working on it, and working with Wesley. But you needed two movie stars to equal “Harrison Ford Movie Star,” and it wasn’t enough.

Tom Wood’s character was killed off near the end of the movie. He essentially retired from acting in the aftermath.

Tom Wood: I still get letters from people grieving for the death of my character all these years later. It’s kind of strange.

Part X – The Legacy

Despite the disappointment of “U.S. Marshals,” love for “The Fugitive” has only grown in the past 30 years. Flip through the channels on any random Tuesday night and you’re likely to come across it on TBS or HBO. There’s a mock Devlin Macgregor Pharmaceuticals website that sells Provasic T-shirts, hats, golf shirts, and coffee mugs. The train wreckage from the shoot remains virtually untouched near Cherokee, North Carolina. It’s become a genuine tourist attraction. Many visitors to the Chicago Hilton demand to see the ballroom and laundry room. John Mulaney has a great bit about the movie in his standup act. And most anytime the cast heads out in public, fans stop them to talk about the movie.

Daniel Roebuck: Without fail, five times a week — and this no exaggeration — five times a week someone will bring up The Fugitive. They’ll say, “It’s that film that if it comes on TV, I have to stop and watch it.” I think it’s the best movie I’m in, and I’m in a lot of really good movies.

Jeroen Krabbé: Someone came up to me one day and said, “You’re such a monster, Dr. Nichols. Such a monster!” Then she walked off.

L. Scott Caldwell: I was at the opera last Sunday, and this woman came up to me and started talking to me about The Fugitive, because it’s always playing somewhere in the world, even now. I just got a residual check last week for about $342. After 30 years, it is still playing somewhere.

Daniel Roebuck: The first thing people might say to me is “This is hinky.” And then they quote my line about dyeing the river green. They also say, “I wish they still make movies like that.”

Andrew Davis: People say to me, “It’s my favorite movie. I can’t turn it off when it’s on.” And based upon residuals and what’s happening when they report from the DGA, or profit participation or whatever, you can see it’s playing all over the world every day.

Keith Barish: It’s a story. It doesn’t rely on the action alone. There’s tension, there’s suspense, and there’s action. It all comes together seamlessly

Cathy Sandrich: They did a big 20th-anniversary screening in 2013. And I walked up to Arnold [Kopelson] and Andy and I went, “I can’t believe how well this aged.” It didn’t age. It’s so relevant, and it’s so current today. I would go see this movie right now, even if I had nothing to do with it.

Stephen Joel Brown: Most great movies start on very simple ideas. And the very most simplistic notion of a man being wrongly accused is very relatable on the simplest level. It hits a chord that’s timeless.

Sela Ward: It’s that classic old-fashioned story where an ordinary guy is forced to become a hero, and he does that with his brain, not an AK-47. It’s just his smarts. If you think about it, his superpower is his integrity.

Tommy Lee Jones: People keep wanting to watch the movie because it’s … well, it’s just so damn good. There’s something to see in every frame that’s relative to the narrative in an exciting way.

Ford was one of the biggest movie stars in the world when “The Fugitive” hit, so the impact on his career was negligible. But it was enormous for Jones.

Daniel Roebuck: Tommy Lee Jones really became the Tommy Lee Jones we know after The Fugitive. That’s what set him on the path. And without him in The Fugitive, would we have all those other movies? Would we have him in Men in Black? No Country for Old Men? I doubt it.

Andrew Davis: He became a major star because of The Fugitive.

Jones himself has little interest in exploring this topic.

Tommy Lee Jones: I don’t know anything about arcs of careers. It’s not something I’ve ever thought about.

Ford and Jones haven’t appeared on the big screen together since “The Fugitive,” but Davis hopes that changes some day.

Andrew Davis: I would love to figure out a way to put Tommy Lee Jones and Harrison together again. I don’t think the budget would be able to finance it, but it’d be great to put them together again. I had a storyline I thought could work. It had to do with the drug-company stuff that’s going on now, and other opioids.

Jones is open to the idea.

Tommy Lee Jones: Well, hell, anybody would want to work with Harrison Ford. He’s a good man, good guy. He is a consummate professional, and he carries a certain amount of … I don’t know. What do you call it? I don’t know if you call it gravitas, but he carries some weight with whatever he does. Hell, yes, I’d like to work with Harrison. Who wouldn’t?

In the meantime, Davis has been working on a 30th-anniversary restoration of “The Fugitive” that will hit theaters this fall in a limited release. The process forced him to painstakingly revisit the movie frame by frame.

Andrew Davis: I was blown away on so many levels by everybody’s contribution, from the actors to the production, to the score, to the way it was edited. You look at these movies today with these amazing chase sequences and these digital effects — then you look at the credits and see 3,000 names of the compositors. But this was real. When I watched it again, I thought to myself, “How the hell did we do this?”

Best of Rolling Stone