Deerhoof share the story behind some of the zaniest guitar recording methods ever committed to tape: “It sounded like the world was ending!”

Deerhoof have never sounded like any other band. They bring elements of punk, art rock, pop, noise and even free jazz crashing together in a joyful explosion of genres that’s limited only by their imaginations – and therefore probably not limited at all.

Guitarists John Dieterich and Ed Rodriguez construct complex interlocking parts that swing pendulum-like from harmony to antagonism and back again. They riff with playfulness, interact with intensity and wholeheartedly embrace the band’s unpredictable nature. Together with vocalist/bassist Satomi Matsuzaki and drummer Greg Saunier, they seem to relish giving cliché the middle finger.

But Deerhoof’s uniquely iconoclastic sound has always had just as much to do with their approach to instrumentation and the recording process itself, which balances a spirit of invention with simply making use of whatever they may happen to have lying around – a badly intonated nylon-string toy guitar, a lone SM57, a motley collection of cans in lieu of a real drum kit.

For 28 years, they have exclusively been making records the DIY way, but their 19th album marks a momentous change of tack. Encouraged by their Joyful Noise Recordings label boss, Karl Hofsetter, they partnered with producer Mike Bridavsky and headed to the renowned No Fun Club recording facility in Winnipeg, Manitoba.

Two weeks and much experimentation later, they emerged with Miracle-Level – an 11-track collection that ostensibly constitutes their “studio debut”.

Having never met Bridavsky prior to the session, John Dieterich explains that the move was a calculated risk, designed to shake up their process. “We like to sometimes put ourselves in uncomfortable positions,” he says. “Maybe ‘like’ isn’t the right word, but we do it occasionally as a practice.”

“Even in a performance, we’re often asking each other complicated and uncomfortable questions, even if it’s just a musical question. Sometimes it’s intentional or sometimes it’s just reacting to a situation where something has gone wrong,” he adds. “In general, our practice is just to never stop and attempt to adapt to whatever situation and react to it creatively.”

Adapting and reacting to being in a purpose-built studio with multiple recording spaces, tons of new equipment and a sympathetic producer at the helm for the very first time has, on Miracle-Level, yielded some spectacularly creative results indeed.

“Mike's whole thing was wanting to make a Deerhoof record in the studio, not make a Deerhoof studio record,” distinguishes the band’s other six-stringer, Ed Rodriguez. As such, the pair applied some tried-and-tested techniques to the environment, but also realized some sonic fantasies that would never have been possible outside of a studio.

Most notably, they constructed a complex rig of amps and microphones designed to capture both the microscopic detail of picks and fingers upon strings, and the sheer, blow-your-head-off intensity of amps being pushed to the absolute limit. It’s a sonic dichotomy that became the defining sound of the record. As Dieterich puts it, “It sounded like the world was ending!”

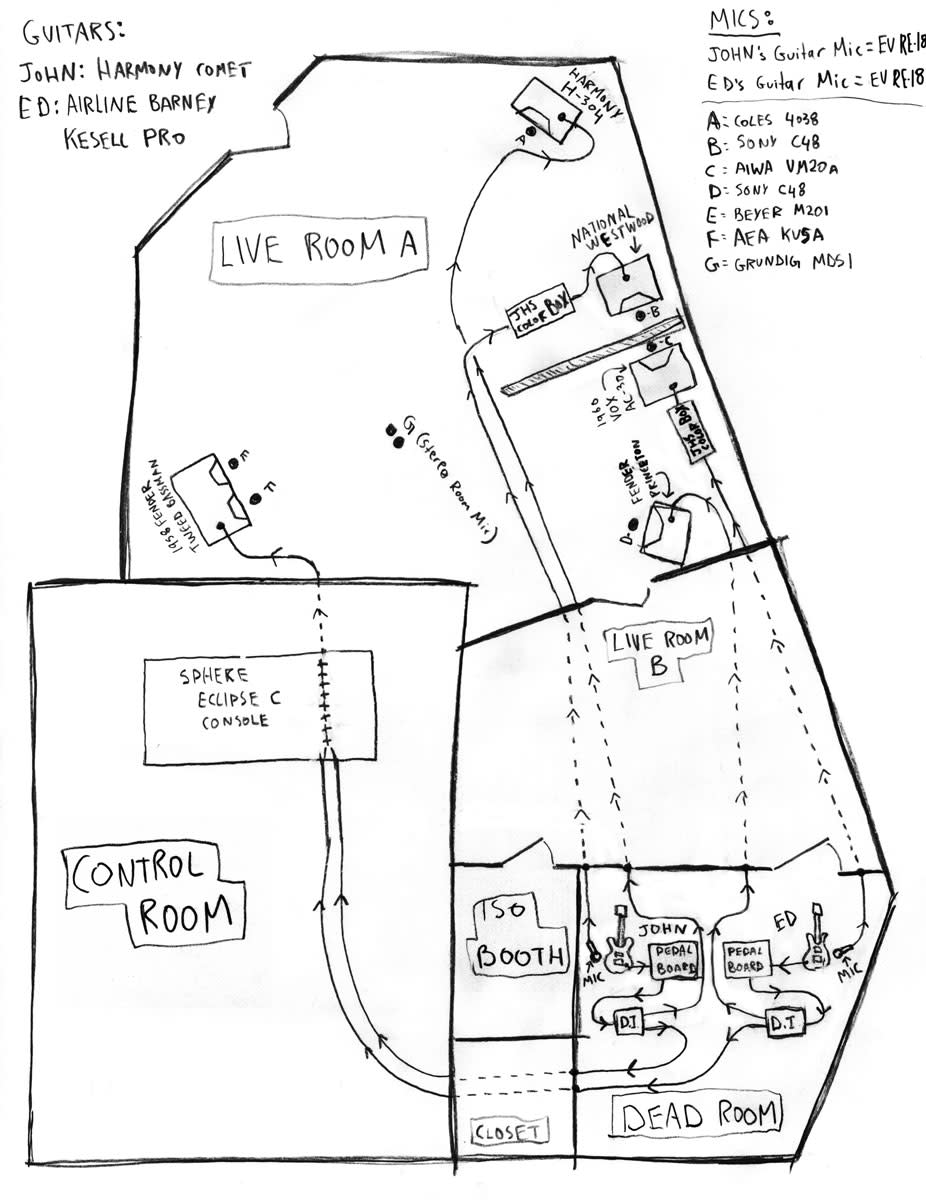

At the crux of it all, Dieterich and Rodriguez would sit together in an isolated room, each playing a hollow-bodied guitar – for Dieterich, a Harmony Comet, and for Rodriguez, an Airline Swingmaster Barney Kessel model. Hypercardioid mics were placed close to these guitars to capture their natural resonance, and the physicalities of the guitarists’ playing.

“We’ve always liked that sound,” enthuses Rodriguez. “A lot of people play guitar not through an amp when they practice and you get used to that sound of the actual contact of the pick and things that you can’t really hear.”

It’s an approach they’ve explored before under their own steam at home, often by simply sliding a tiny microphone – the type you might find on a phone headset – into the f-hole of their guitars. “John and I have talked about this kind of thing for many years and what a great sound that is to actually have that visceral contact,” explains Rodriguez, before his counterpart jumps in to add that the magic of the technique lies in the fact that “it’s just more violent-sounding.”

Next, they ran signals from each guitar through the pair’s respective pedalboards and into cranked amps situated several rooms away: a Harmony H-304 and National Westwood for Dieterich and a Fender Princeton and 1960 Vox AC30 for Rodriguez.

To give an idea of just how extreme the volumes they were operating at were, Dieterich laughs: “The room we were in with the actual physical guitars was two rooms away, and even opening up the door closest to us one inch – and these are like, the world’s most soundproof fancy doors – was like wide-open feedback! It was completely insane.”

Finally, they ran direct outputs from both guitars into another screamingly distorted amplifier – a 1958 Fender Tweed Bassman – that combined both signals, leaving each one to “fight for primacy,” as Dieterich puts it – and giving a whole new meaning to the term ‘combo amp.’

“When the two guitars are in the same range and fighting for the same frequencies, it all depends on whose guitar has a little bit more punch in that area to cut through a little bit more,” explains Rodriguez.

“With the way the guitars are, nothing’s consistent. John’s guitar might cut through with these three notes, while mine might cut through with these two, so it’d be all over the place and create this whole new thing.”

What John and I have is that extreme comfort with what’s uncomfortable to a lot of people

“We’re always trying to get our touring gear smaller,” he adds with a smile. “We’re always half-joking – or probably 20 percent joking and 80 percent serious – trying to think if we could both tour with just one amp. We haven’t done that yet, but we finally got the chance to try that in the studio.”

The three distinct kinds of signal captures were then blended to create the imposingly multi-dimensional guitar sound that makes Miracle-Level such an immersively riotous listen – where the triumphant ends more than justify the unusual means.

But it was a convoluted process that required a specific environment, extreme volumes and equally extreme isolation – as well as a savvy producer on hand to tackle (with the help of a JHS Colour Box) the inevitable ground loop issues that ensued from having multiple signals and splitters.

As Rodriguez concludes, “Once it was actually set up and operational, it was like a whole new instrument, but I don’t think it’s something that we ever would have tried at home.”

The sonic possibilities granted by this almost living, breathing Franken-rig that Dieterich, Rodriguez and Bridavsky had built and tamed somewhat negated the need for such wild experiments in the pedal department as we’ve heard on previous Deerhoof records.

“What we wanted was to have interesting sounds, but to keep jumping around between sounds to somewhat of a minimum because that would also make things really easy for recording the whole thing in this unknown setting, with this unknown person,” explains Rodriguez.

But there was also another, more operational factor that meant tap dancing around with infinite stomps was not going to be a goer.

Because you had this wide open acoustic mic on your guitar, you had to be really strategic about when you hit your pedals because the mic was also going to pick that up

“Because you had this wide open acoustic mic on your guitar, you had to be really strategic about when you hit your pedals because the mic was also going to pick that up,” says Dieterich, who has previously employed vocalist Satomi Matsuzaki to manipulate his pedals while he rips on guitar, such is the head-splitting complexity of performing both tasks at once.

In general though, and in live settings, Rodriguez distills the duo’s pedal philosophy as one of give and take. “John tends to use a lot more dynamic pedals that have a lot more character to them, so I tend to set up my pedals to be a little bit more straight in order to not get in the way,” he explains. “That’s one thing when you have two guitarists, especially two guitarists like John and I who have really similar aesthetic tendencies.”

“What can happen really commonly with two guitars is there are two distortions that sound the same. Or, one guitarist goes up really high and starts doing noodly stuff and the other guitarist immediately has to do it, too,” says Rodriguez, speaking with 25 years’ worth of experience in successfully navigating life in a two-guitarist band. “It’s that compulsion of when something sounds cool, wanting to do it too. So, for us, there’s been a lot of fighting those urges.”

As such, Rodriguez will, for example, reach for a spring reverb if Dieterich has already slapped a cool delay sound on his guitar. Or, he’ll use an Octavia to move his sound into a different range when Dieterich has already claimed the mids with another kind of distortion.

The thoughtfully nuanced partnership that exists between the two players has been the creative engine that’s powered Deerhoof’s music-making capabilities for so many years. But their profound familiarity is yet to result in any semblance of predictability.

“What John and I have is that extreme comfort with what’s uncomfortable to a lot of people,” smiles Rodriguez, who prides Deerhoof on not being “a counting band” and celebrates the “totally absurd, falling apart, chaotic thing” that gives their live performances such an unquantifiable, noisy magic.

Likewise, Dieterich’s natural aptitude for breaking new sonic ground remains as joyfully off-kilter as ever. “I’m working on a recording right now,” he tells us with glee, “and adding a ‘guitar solo’ to it that just essentially sounds like malfunctioning fax machines – that’s the stuff that seems fun to me!”

Miracle-Level is out now via Joyful Noise Recordings.