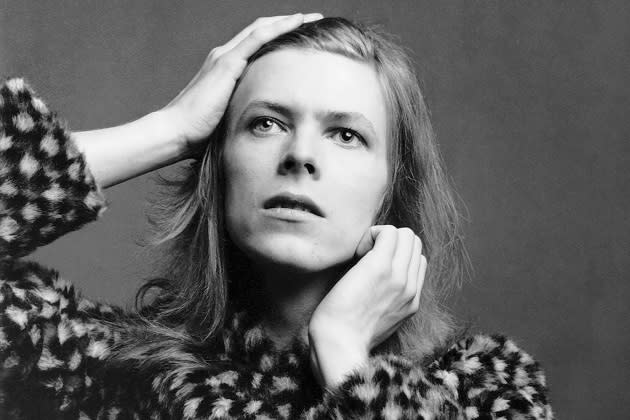

David Bowie’s ‘Divine Symmetry’ Box Set Shows How He Made ‘Hunky Dory’ His Mission Statement

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Five years after the release of David Bowie’s first masterpiece, Hunky Dory — which replaced the perception of Bowie as a one-hit space oddity with the idea Bowie as an ever-ch-ch-changing moon-age messiah — he offered up some characteristic mythmaking. In a 1976 Melody Maker interview, Bowie claimed Hunky Dory‘s “Song for Bob Dylan,” a piss-take extraordinaire that Bowie had shrugged off by saying it was how “some” people saw Dylan, in fact, “laid out what I wanted to do in rock.” “It was at that period that I said, ‘OK, if you don’t want to do it, I will,'” he continued. “I saw the leadership void.”

Divine Symmetry, a new box set subtitled The Journey to Hunky Dory, suggests Bowie’s claim was only partially true. With five years of hindsight, he was hiding the panic he had felt while making Hunky Dory. The collection’s treasure trove of five discs contains raw demos, radio sessions, a rare live concert, and alternative mixes that show how Bowie was desperate to figure out his next step. He was mired in the quicksand of novelty status, and after his third album, 1970’s The Man Who Sold the World, bombed, he clammed up. He mostly stopped touring, and he bickered with his backing band. But a trip to the U.S. reinvigorated him, allowing himself to open up to nuanced pop songs that traded an ethos of inclusiveness for the solitude of his previous record, giving him the courage he needed to figure out a path forward.

More from Rolling Stone

David Bowie's 'Hunky Dory' Gets Deluxe Reissue Treatment Including Unreleased Tracks

'Moonage Daydream' Isn't Just a Bowie Doc -- It's a Trip Through the Thin White Duke's Mind

David Bowie Estate Links Up With Nine Artists for New NFT Project

After traveling across the States, he started writing songs for his friends to perform, à la Andy Warhol’s Factory, and wanted to tour as a troupe. “Song for Bob Dylan” was meant for his buddy George Underwood to sing, while “Andy Warhol” was for Dana Gillespie, who performed the tune with a Nico-like drawl on the BBC Peel Session included here. “Oh! You Pretty Things” was a hit for Herman’s Hermits’ Peter Noone before Bowie released it. If he couldn’t make it as an artist, he knew he could at least write good songs. He just needed to decide who he was.

Divine Symmetry’s demo recordings, nearly all of which have never been officially released, show all the ways Bowie tried to figure out how to fill Dylan’s “leadership void.” All of the discarded demos make up a blueprint for the rest of his career, as he tried on different personae. On the rough version of “Song for Bob Dylan,” he imitates Dylan’s voice, which he describes as sounding like “sand and glue,” and he plays tinny harmonica throughout it (he wisely ditched both affectations by the Hunky Dory sessions). Similarly, on the primordial “Queen Bitch,” his mordant Velvet Underground impression, which he renders a little slower here, he chuckles mid-verse coolly like Lou Reed. (His solo acoustic cover of “Waiting for the Man” sounds similarly deferential.) And on “Port of Amsterdam,” an anglicized Jacques Brel cover (a nod to another one of Bowie’s heroes, Scott Walker), he belts desperately about drunken sailors and sullen prostitutes. (“Amsterdam,” incidentally, nearly closed out Hunky Dory before Bowie wrote the transcendent “Bewlay Brothers” at the last minute.)

The songs that didn’t make it to Hunky Dory studio versions are even more revealing. Each shows Bowie was woodshedding new characters. He auditions Kurt Weill songcraft on “How Lucky You Are (aka Miss Peculiar)” with oompah bass and “li-li-li” refrains. He tried convincing Tom Jones to record it but failed. “Looking for a Friend,” written for his horribly named Arnold Corns side project, could be the Band’s response to “Song for Bob Dylan” with its country-funk rhythm and folky chorus. The twangy “King of the City” could be an early Bee-Gees folk number (think “I Started a Joke”) but with a little more grit, and Bowie’s general approach to the song’s melody echoes in his later hit, “Ashes to Ashes.” And “Right On, Mother,” eventually cut by Peter Noone, sounds here a bit like Frankie Valli singing Billy Joel right down to its bizarre lyrics about his mom accepting his choice to live in sin with a woman. The folky, morose “Tired of My Life” would become “It’s No Game” on Bowie’s Scary Monsters album a decade later, and listening to the version here, it’s clear the song was too depressive to fit what would become Hunky Dory.

The rest of the demos show how Bowie developed his sound and stuck to his vision when he got into the studio. The acoustic “Quicksand,” recorded in a San Francisco hotel room for Rolling Stone’s John Mendelsohn who wrote the magazine’s original review, contains some fumbled lyrics but mostly the demos reflect the songs as recorded. They’re just sparser. He plays “Kooks,” his song for recently born son Zowie, on a 12-string guitar (or 11-string, according to ex-wife Angie Bowie’s memoir), and his piano playing on the early version of “Life on Mars?” sounds plodding as he reappropriates the chords from Frank Sinatra’s “My Way” in an attempt to write a better song than the Chairman’s. (Yes’ Rick Wakeman played the rumbling, filigreed album version.) “Changes,” taken from a scratchy acetate, sounds similarly rudimentary, and includes Bowie sighing like a train when he’s not singing. And “Shadow Man” shows the promise of a song that could have rivaled anything by Elton John, but Bowie didn’t cut it for years, a version eventually coming out around his Heathen album.

A facsimile of Bowie’s notebooks from the period, included in the box set, suggests he had dozens of other songs, too, and it’s rumored he’d already written most of Ziggy Stardust during this period. One curiosity is Bowie’s discarded lyrics to “Life on Mars?” with the line “Just kiss the face of a subhuman race,” several instances of the song title “Andy Warhole” [sic] (which explains why he corrects producer Ken Scott to say “hole” on the song intro), and a reference to a track titled “Charles Manson,” possibly discarded in 1971 when Bowie realized Manson wasn’t just some hippie railroaded by the Man but truly a dangerous criminal. On one page, Bowie, still in his early 20s, scrawled, “I believe my mental condition is extremely illegal.” On the notebook’s cover, Bowie misspelled Hunky Dory as Hunky-Dorrey? and Hunky-Dorey, even sketching a record crate on the back sandwiched by a “Dorey” logo. Inside are several sketches of Bowie’s costumes, showing just how he figured out who he was.

The three live recordings also show Bowie’s maturation. On the Peel Session, recorded a few days after Zowie’s birth, he plays an early version of Hunky Dory’s “Kooks” (or “Cukes” as Bowie mispronounces it), and the Sounds of the 70s: Bob Harris recording, Bowie sounds diffident as he readjusts himself to rock stardom after months away from the spotlight. On the latter performance, he sings a stunning “Oh! You Pretty Things” by himself at the piano; the “mamas and papas” part of the chorus comes through clearly this time, since there are no backup singers obscuring it. And on “Andy Warhol,” he and Mick Ronson thatch their acoustic guitars together for a little more depth.

On the collection’s third concert, a nearly complete recording of a gig in Aylesbury on Sept. 25, 1971 (still months before Hunky Dory’s release), you can hear Bowie settle into his confidence. He begins shyly, asking Ronson to “get a bit nearer” then laughing as he jokingly adds “to the mic,” since Ronson probably just moved closer to Bowie. He nervously shrugs off “Space Oddity” (“This is one of my own that we get over with as soon as possible,” he says) and finally sounds at ease when his backing band joins him for “The Supermen” and “Pretty Things.”

Although some of the songs sound rough (he admits he doesn’t know how to play “Changes” and guitars feed back on “Andy Warhol,” or “Andy Wuh-huh,” as he calls it), the audience cheers louder and louder right up to the covers of Chuck Berry’s “Round and Round” and the Velvet Underground’s “Waiting for the Man,” which ends the set. “We really haven’t got any more numbers,” he tells the crowd of about 500 chanting for more. “We only rehearsed for today and I killed myself singing.” The show’s promoter, saying good night at the end, calls the performance “one of the greatest evenings of my life.” You can hear how this is the moment when David Bowie realized he could fill the void and lived up to his threat in “Changes”: “Watch out, you rock & rollers.”

A disc of alternate versions of Hunky Dory songs also contains revelations. The full recording of “Life on Mars?” doesn’t fade out at the end, so you can fully hear Ronson cursing the ringing phone that ruined the perfect take. And several remixes show off different sides of Hunky Dory mainstays; the best are the Biff Rose cover “Fill Your Heart” — which was a Xerox of Rose’s recording on the record (even Tiny Tim played with the arrangement when he covered it) — but now it feels less claustrophobic with only a piano arrangement, and a sparser “Bewlay Brothers” with a wider array of weirdo vocals at the end. (The final disc, a Blu-ray, contains high-def versions of tracks from the rest of the set.)

As a whole, Divine Symmetry extends the canvas of Hunky Dory. He was willing to try anything to shake the one-hit wonder stigma and eventually focused the album into a delightful and welcoming instant classic. In a 1971 NME interview, he asked, “How can anyone be a serious pop artist at 24?” but by the end of the year, when Hunky Dory, was released, he answered his own question. Within months, he’d be redefining himself again, telling Melody Maker he was gay and dying his hair red to become Ziggy Stardust and record many of the rest of the leftover tracks he’d written at the same time as Hunky Dory. It was only then that he filled rock’s “leadership void” — and adopted the rock-star pomp to back it up.

Best of Rolling Stone