David Attenborough lying on the beach with a turtle isn't the most amazing thing you'll see in 'Blue Planet II' this week

Viewers of Blue Planet II have no doubt gotten emotional during the first six episodes of the BBC America series, but Saturday’s new installment, “Our Blue Planet,” will hit home in a different way — it makes it personal.

Much has changed since the 2001 debut of the original series, starting with our understanding of how humanity is affecting the oceans. “The oceans are more fragile, perhaps, than we thought before. That’s something that dawned on us during the making of the series,” Blue Planet II executive producer James Honeyborne tells us. “What we wanted to do in the [penultimate] episode was really inspire people, not make them feel they couldn’t do anything about it. It’s an inspirational story of heroic individuals, scientists, conservationists, whoever they are, who are out there working hard, tirelessly, in pursuit of making the oceans a healthier place again. And that’s vital for us, because the planet needs a healthy ocean. That’s fundamental to life on Earth.”

As you see in the sneak peek above, change can start with one person, like Len Peters, who has worked to save endangered leatherback sea turtles, the largest of all turtles, on Trinidad. Coming ashore to lay their eggs makes them an easy target for hunters. Peters began patrolling the beach at night to protect them (and was cursed and threatened with a machete for it). He encouraged tourists to visit the turtles and trained locals to be their guides. He continues to speak in schools to cultivate the next generation’s appreciation for the leatherbacks, which have now made a comeback on the island.

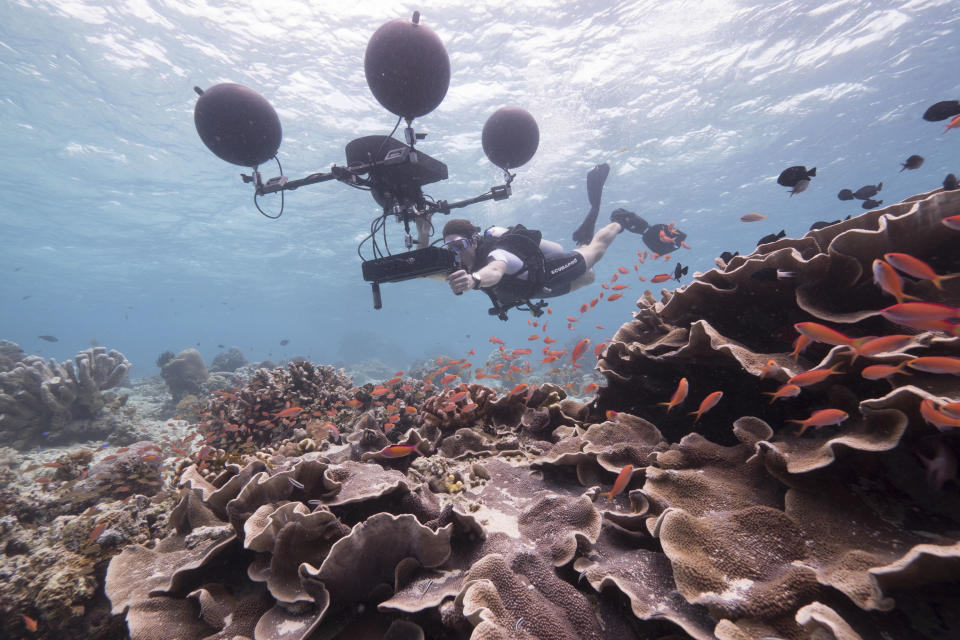

Another fascinating sequence shows just how much scientists still have to learn. Marine biologist Steve Simpson is studying how fish in coral reefs use sound — “pops and grunts and gurgles and snaps” — to communicate with each other. While filming the family of talkative saddleback clownfish we saw earlier in the series, Simpson floated a decoy coral trout, one of the clownfish’s main predators, near the family’s anemone and recorded the large female’s alarm calls. “But that discovery has led to a serious worry,” narrator Sir David Attenborough says in the episode. When a small motorboat travels overhead, the fish become distracted. “Unable to make themselves heard above the noise of boats, the family can’t warn each other of danger, and so they are now vulnerable to attack,” Attenborough explains.

“We’re changing that world because of the sound we’re making,” producer Orla Doherty tells us. “We didn’t know this stuff even maybe five, 10 years ago. There’s so much going on down there that we’ve just got no idea about.”

Some discoveries are particularly painful. In this week’s episode, Australian marine biologist Alexander Vail, who introduced the Blue Planet II crew to the tool-using tuskfish nicknamed “Percy the Persistent,” who we saw earlier in the series, admits he cried in his mask when he saw that 90 percent of the coral at Lizard Island had bleached in 2016. Warming seas can cause corals to lose their colorful algae, turning them white.

“I think what was so devastating for Alex was this is his backyard. This is literally where he grew up,” Honeyborne tells us. “He’s been snorkeling out there since he was an adult, and to see it devastated for the first time was shocking for him, and then to know that it was part of this huge picture of very fast change that appears to be happening — I’m sure his tears were very real. This is an unfolding situation that we’re in now. Probably half the world’s coral has been bleached to some extent in the last three years, and the impacts are great. Back-to-back bleachings [in 2016 and 2017] had never been recorded before. So for him, it was kind of an unprecedented disaster. Every time it happens, the corals become weaker.”

The “Big Blue” episode of Blue Planet II has already covered how prevalent plastic is, and how it travels from ocean to ocean, but this week, we meet Lucy Quinn of the British Antarctic Survey, who catalogs the plastic objects wandering albatross chicks have regurgitated after being mistakenly fed them by their parents. As you see in the clip above, a plastic toothpick can be fatal.

“Everywhere we went, we saw plastic. Plastics are there in every ocean, and the extent of the problem is grave and huge and far-reaching,” Honeyborne says. “The really big bits of plastic are a problem in terms of entanglement. We were filming in British Columbia when we found a whale that had been entangled in the plastic fishing lines that link those pots. We stayed with that whale for a day until the emergency services were able to come out and cut it free. There’s the ingestion issues: Plastic bags, for example, get eaten by a large number of creatures, including turtles and albatrosses, and are clearly a threat. And that one toothpick — that was shocking what that did to that albatross chick. Every albatross chick feels so precious, doesn’t it? Just one disposable, single-use plastic killed it. Then, of course, as plastics break down, they become much smaller micro plastics, and they get eaten by all sorts of sea creatures, we’re now discovering. They’re finding plastics on the deepest trenches on the planet. We’re finding plastics inside the bodies of filter-feeders, like edible mussels and things like that. A lot of this is emerging science. Scientists are looking very intently at how the small bits of plastic interact with toxic pollutants, chemicals in the oceans, and are these plastics that are being ingested toxic? We don’t have all the answers here. We don’t know to what extent this is entering the food chain, but it is clearly a sort of cutting-edge issue that needs exploring.” (See: The possibility of a mother’s milk being contaminated posed as one potential cause of death for a newborn pilot whale calf in the “Big Blue” episode; the mother refused to let go of its body for days as she mourned.)

Of course fishing is a danger too. In this episode, shark biologist Jonathan Green of the Galapagos Whale Shark Project says it’s estimated that thousands, or tens of thousands, of whale sharks are taken every year. To save them, he’s trying to solve the mystery of where they give birth — and what route their migration takes — to get those waters protected. “A lot of these big sea creatures are long-distance migrants. They travel over thousands of miles of ocean, like the whale sharks do. That’s on the high seas and is largely unregulated and unpoliceable,” Honeyborne says. “That’s potentially a big issue for these creatures if they’re being hunted. Marine-protected areas are, if they’re well-managed and policed, effective at being able to reestablish and repopulate populations of sea creatures.”

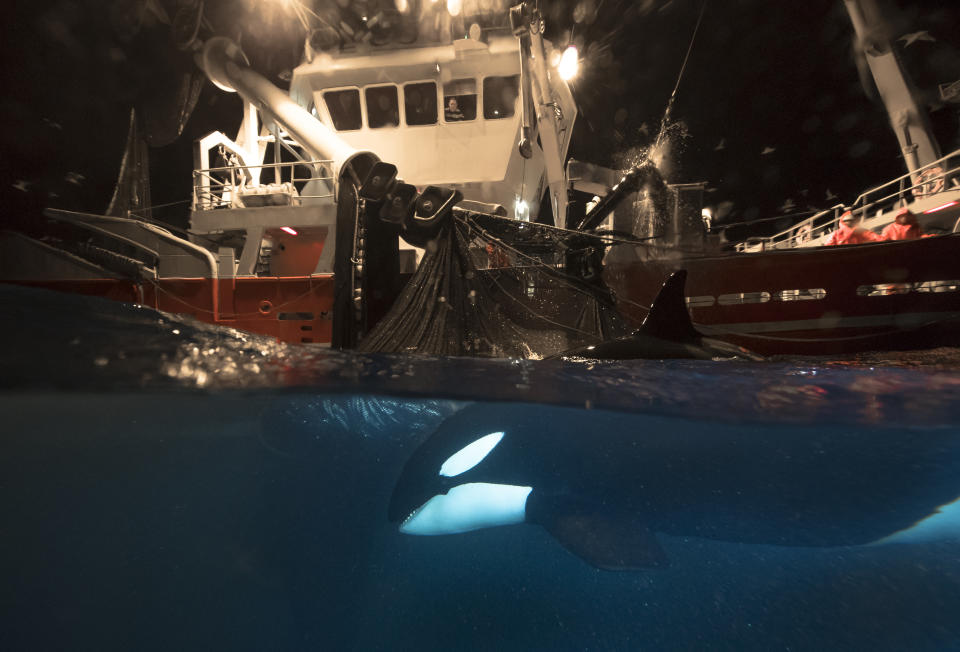

Saturday’s episode profiles one such success story: Back in the late 1960s, herring had all but disappeared from the fjords of Norway, and orcas were being killed because they were viewed as fishermen’s rivals for the fish. But by regulating the fishery and protecting the whales, both populations are now thriving — so much so that a billion herring pour in during the winter, attracting 1,000 orcas that strategically hunt in pods (as we saw in the first episode of the series).

The message Blue Planet II wants to leave viewers with is there is hope — if we take action. “We asked [the scientists] all the same question: ‘How do you feel about the future?’ Unanimously, they were all optimistic. You could ask yourself, is that just part of the human condition? But no, I don’t think so,” Honeyborne says. “What we do know is that the oceans have an incredible capacity to bounce back, in terms of their health. A really good example of that in the U.S. is Monterey Bay, where 50, 60 years ago, it was fished to a point where it was polluted and all the big animals in there had been hunted or chased away, and the whole ecosystem collapsed, died. Yet today, when you go there, it’s one of the greatest spectacles in the oceans. The ocean does have a capacity to recover, if we just take that pressure off it and just give it a chance.”

Blue Planet II airs Saturdays at 9 p.m. on BBC America.

Read more from Yahoo Entertainment:

‘Blue Planet II’: See what happens when penguins come between battling elephant seals

The most heartbreaking sequence in ‘Blue Planet II’: A pilot whale mourning her calf

The most terrifying sequence of ‘Blue Planet II’: The Bobbit worm

Why ‘The Deep’ episode of ‘Blue Planet II’ is the one you can’t miss

‘Blue Planet II’ premiere: Bird-eating fish and 5 more sequences you’ll be talking about