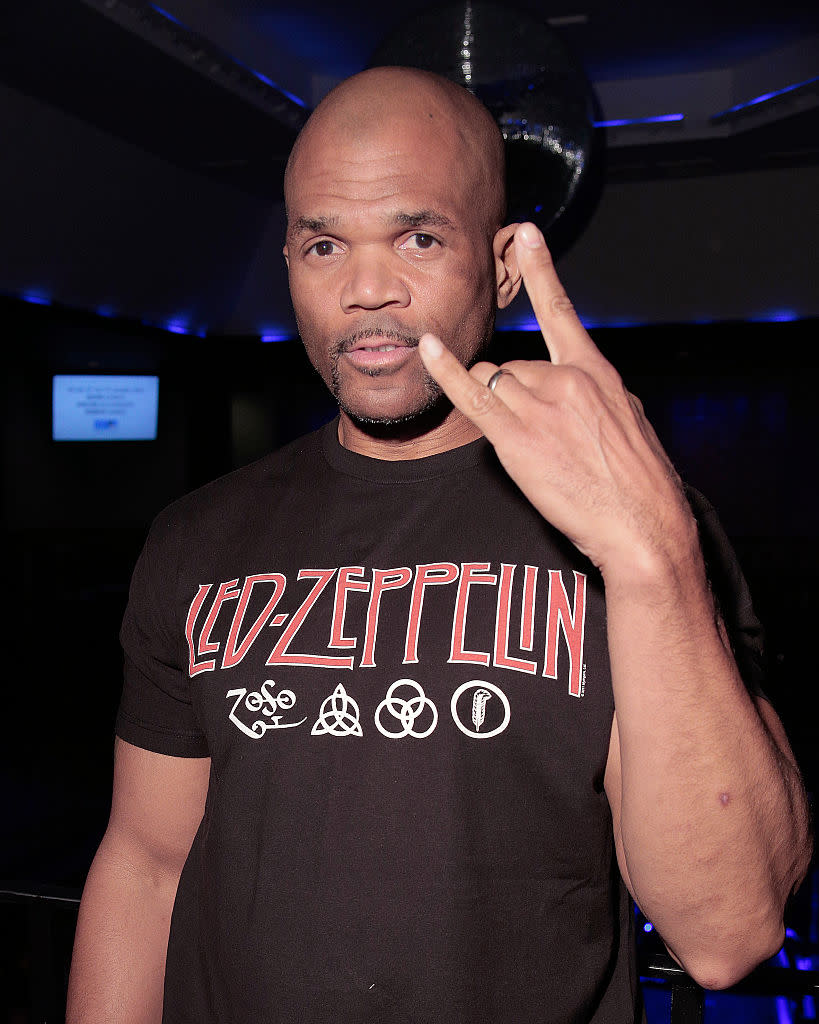

Darryl ‘D.M.C.’ McDaniels on Race Relations, Police Brutality, the State of Hip-Hop, and His Suicidal Past

As a member of the groundbreaking hip-hop group Run-D.M.C., Darryl “D.M.C.” McDaniels rose to stardom rapping about his family, neighborhood, and mic-rocking skills. His delivery, like that of his fellow rapper Joseph “Run” Simmons, was witty, well-timed, and lyrically positive. With exciting rhythms, live guitars, rock ‘n’ roll samples, and relevant social and political messages, Run-D.M.C. became the first rap act to score a platinum record with Raising Hell, featuring their genre-shattering collaboration with Aerosmith, “Walk This Way,” which laid the groundwork for the future of rap-rock.

Related: 30 Years Ago, Run-D.M.C. and Aerosmith Tore Down Walls With “Walk This Way”

Now McDaniels is working on two major rock-oriented projects. The first is an album of originals, D.M.C. (Dynamic Music Collaborations), recorded with Sum 41, Travis Barker of Blink-182, Chad Kroeger of Nickelback, Justin Furstenfeld of Blue October, John Moyer of Disturbed, and Myles Kennedy of Alter Bridge. McDaniels also has a rap-metal project coming out called Fragile Mortals, which features former Exodus vocalist Rob Dukes and ex-Pro-Pain bassist Rob Moschetti.

“We got a record called ‘Under the Skin,’ And one of my rhymes is, ‘My best friends, they’re all white/Mess with them and we will fight/They’re all white and I am black/You best believe they got my back,’” McDaniels tells Yahoo Music. “When that record drops, motherf—ers are gonna go, ‘Oh, s—! Did you all hear that one?’”

But don’t expect McDaniels to delve into his music much in his recently released memoir, Ten Ways Not to Commit Suicide. Instead, he confronts the trials and tribulations he faced after Run-D.M.C. became famous, and the suicidal despair that hit him when he was pressured to keep writing formulaic hits rather than explore other creative possibilities. As he explains in the book, the frustration of remaining stagnant in a rapidly growing music scene made him feel worthless. The more depressed he became, the more he drank and did drugs, until he contracted a severe case of pancreatitis.

“When I got away from doing what I wanted to do creatively, that’s when everything went wrong,” he continues. “I lost my love of comic books, I lost my love of the music, I suppressed the way I wanted to write a song. And all I wanted to do is drink. It felt like my opinions didn’t matter. I don’t drive a f—in’ Bentley. I drive a pick-up truck. And I listen to Creedence Clearwater Revival. That’s what I wanted to rhyme about. But no one was letting that happen.”

In his memoir, McDaniels says he was so profoundly expressed during a 1997 tour of Japan that he was on the verge of killing himself. “I was hearing adversity and negativity all around me. I’m hearing, ‘Don’t say that rhyme, D. Rhyme like this. Rhyme about this.’ I went along with that, and that’s what killed me. That’s why, even though I didn’t jump off the bridge, drink the poison, shoot myself in the head, or hang myself, I was still killing myself in two ways: by drinking that alcohol to suppress how I really felt, and by not doing what I felt. If I’m holding in what I need to release, then what’s my purpose? What’s the use of me being on this earth?”

The situation got worse before it got better. McDaniels suffered serious voice problems that left him unable to rap the way he used to. More significantly, after having valued and written about the stability of his family upbringing, he found out his was adopted. Then his father died, leaving him on the verge of collapse. Desperate for help, McDaniels entered rehab and started therapy, which put him in touch with feelings he had suppressed for years.

“I discovered where the suicidal thoughts were coming from, and then I was able to go back and deal with them,” he says. “Once I was clean and clear, I started remembering how I felt before I became depressed. And I could see when it began and where it all came from.”

While Ten Ways Not to Commit Suicide candidly addresses addiction, insecurity, and depression, the rapper also writes about the forces that pried him out of his hole, including the love of his wife Zuri and son D’son, vigorous exercise, working with underprivileged kids, launching the comic book line Darryl Makes Comics, and creating new music. Much of that music, like the above-mentioned “Under The Skin,” is confrontational and aggressive – a significant departure from the safe, non-threatening rhymes of Run-D.M.C.. McDaniels is writing what he feels is some of his most poignant, provocative music to date, and he’s speaking his mind with renewed conviction.

Here, the rap icon discusses the current state of hip-hop, why the rap community doesn’t value the pioneers of the movement, what can be done to stop the crime and violence that’s infecting many urban centers, and the recent spate of police brutality tragedies.

YAHOO MUSIC: Run-D.M.C. is in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, and is remembered as a legendary rap group. But there are kids who are just learning about rap music that aren’t familiar with how important you were.

DARRYL MCDANIELS: It’s definitely a tragedy that people don’t know the history of the music. Grandmaster Flash & The Furious Five is the first hip-hop act ever to be inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame because of “The Message” and nobody knows about it. That is so crazy! XXL, Source, MTV, VH1, they should have put specials out about that achievement, but nobody cares.

Why the lack of awareness?

You know what’s missing? It’s the responsibility and the unwritten rule that you need to explain the importance of putting the history of the art and the culture up on a pedestal. And that’s so lacking in hip-hop. When Neil Young comes out with a new record, Rolling Stone will give him the cover and at least 10 to 12 pages about what he used to do, why he’s known for doing it, and what he’s about to do now. If Melle Mel does something, he’s on page 333 in the back of the rap publication. That’s f—in’ disrespectful.

Is the media to blame?

No, it’s the culture. When the Rolling Stones or Aerosmith sit down with you and start talking about rock music, they ain’t gonna just talk about themselves. They’ll talk about all the black blues artists that influenced them. If you sit down with a rapper now, they’ll say, “Yeah, yeah. I like Naughty by Nature. I like Rakim.” And that’s all you’ll get from them. That’s a big disservice to the music and everyone that came before them. If you sit down with me, I’ll talk about Grandmaster Flash & The Furious Five, the Cold Crush Four MCs, the Treacherous Three, and the Funky Four Plus One, because they were there before a rap record was ever made. Me and Run are dope because of that. This culture exists because of that. There’s a disrespect that causes the disconnect between the generations. And that is driven because the industry has become more important than the music. Whatever genre there is, once it becomes commercial it will become diluted and polluted unless all of the people within that culture fight for it. And we have not fought for the respect of hip-hop music.

Does the industry promote misogynist, homophobic, violent hip-hop because it’s more marketable than positive rap?

Let me put it this way: Wise Intelligent of the Poor Righteous Teachers said, “Do you think the emergence of all this negative bulls— hip-hop is historically something that just happened?” Oh, hell no! They don’t want a man that looks like Young Thug rhyming like KRS-One. They don’t want a man that looks like Lil Wayne rhyming like Chuck D. Why? ‘Cause that changes things in the world.

Are the industry puppet masters pulling the strings so rap celebrities aren’t overtly political?

Just look at what’s out there and you’ll see. In their eyes, as long as we rhyme about sippin’ syrup, sex, taking drugs, fighting, shooting, and disrespecting our women, we’re in a good place. But when a rapper comes along saying school is cool, things can change. When I rapped, “I’m DMC in the place to be/I go to St. John’s University/Since kindergarten I cried for knowledge/After 12th grade I went straight to college” [on “Sucker M.C.’s”], I rapped with the same ego and enthusiasm as emcees who rhyme about tearing down their neighborhoods by selling drugs and naming themselves after the movie character Scarface and John Gotti. When I rhymed about good things with the same energy, what happened? Dudes stopped selling drugs and gangbanging and started going to get GEDs, high school diplomas, and degrees.

What do you think about the leaders of the scene today — guys like Kanye West, Jay Z, Drake, and Lil Wayne?

They’re good, but there are so many other people that should be right up there next to them. And the industry — these corporations that control everything — know that. About seven years ago Grand Puba, who used to be in Brand Nubian, put out a record called “I See Dead People.” That was a one of the best records out and he said one of the most powerful lines ever that shows what’s going on in our communities with all these police shootings and with these economic scenarios: “Nowadays the old heads are afraid of the youth/Remove the tree from the roots and you kill all the fruits.” But did the radio play it for the community that should have heard it? No, they didn’t.

Maybe the scene needs another powerful group like Public Enemy to come along that can’t be denied. When they first came out they had a strong political message, they got through to their audience and white America was terrified.

Yeah, they were terrified of P.E. because Chuck wasn’t saying, “Kill white people. I’m against white people.” Chuck was trying to tell black people to do what the white people in power do economically, socially. When we stand together, we’re unstoppable. But go to a Public Enemy concert today. It’s all white people there throwing their hands, fighting the power. Our own black people are saying, “We don’t want to hear none of that s—. We wanna take that pro-black s— out of there.” So that’s the problem. There is nothing representative of how to turn around and fight back within the struggles we’re facing. Right now there’s no desire to do better and be better and create something for your generation. Right now the attitude is, “Yo, let me just be a drug dealer so I can get this money now.” Kids have power now, but they’re not using it because they’re so busy looking at Twitter, seeing what’s on Instagram, and listening to and following what’s on radio and bulls— ass video channels.

Don’t kids realize contemporary rap is entertainment? Doesn’t that prevent them from taking the lyrics seriously?

The concepts, ideas, and images that our young people are constantly shown makes them think, “Oh man, learning to play the violin ain’t cool. I gotta have tattoos. Hey, if I want to succeed I can only be a rapper, an athlete, or a drug dealer.” Oh hell no, young man! You can be a journalist, a scientist, a professor, a lawyer. Right now we are not exposing our generations of young people to all the productive, profitable possibilities that exist for them. And that’s what Run-D.M.C. did. That’s what De La Soul, that’s what Public Enemy encouraged, and that’s missing right now. It’s a damn shame.

Right now there’s a scary race division in America. And the recent acts of violence, both with cops jumping the gun and killing Philando Castile and Alton Sterling, and the angry reaction by a man who retaliated by shooting five cops at a protest in Dallas, have ignited a powder keg.

It’s nothing new. It’s been happening and people are frustrated. When they riot, psychologists are forgetting they’re not just stomping on the police car. They’re not just burning a building down. This is how they feel inside. Why? Because it’s the same cycle over and over and over. But what’s also dangerous is that we, as communities, are in a place where there’s this mentality: When the white cop shoots the black guy, that’s wrong. But in Chicago or Camden or Newark, when the black guy shoots the black guy, that’s a way of life. It’s a racial problem that is enhanced and empowered and catalystically turned into nitroglycerin.

You were indirectly affected by black on black violence in 2002, when Jam Master Jay was shot and killed at recording studio in Jamaica, Queens. No one was arrested or charge with the killing. Does it eat you up inside that justice wasn’t served?

I’m not mad at the individual that shot Jay. I’m angry, but my fight isn’t with the individual, my fight is against the mind state that would cause any individual to shoot Jam Master Jay in the head. That’s what makes me get out of bed every day and figure out how can I communicate and represent something that’s powerful. We continue to talk about what happened, instead of talking about how not to make that happen. Look at CNN. They tell you what happened, but nobody talks about how we gonna stop that s— from happening again. At least hip-hop, when we came along, we gave a solution: “Be cool, go to school/ Don’t mess with drugs and thugs and you will rule.”

Do you have anything to say about the Philando Castile and Alton Sterling murders?

There’s a truth about these shootings, and I’m talking about all of them where a white officer kills a black guy. In all of these situations, the bullet didn’t have to be discharged. The lady that was with Philando Castile had it on camera. The cop shot this motherf—er and he died. The dude in Ferguson: The motherf—er stole blunts. Damn. We stole 40s out of the local corner store [when we were young]. He didn’t have to die for that. He should have been rightly prosecuted, but what happened in that situation is the cop got punched in the face and he got mad and shot him. He could have gone, “Yo, I just got punched in the face. Imma wait for backup and take this dude down.” In all of these instances that have been reported over the last five or 10 years, the situation is similar. The bullets didn’t need to be discharged. The first thing we have to do is teach these motherf—ers not to shoot over some bulls—. The people that got shot wasn’t in a hostage situation. Remember a couple years ago in L.A. when the two dudes in body armor robbed a bank and then went through the city shooting? That’s when the cops should pull their guns out!

So how should the community react in these situations? Are protests and riots the answer?

Here’s what we gotta do. We gotta go into every precinct and look at all the complaints, talk to all the officers, and talk to all their families. If there’s an officer working for any department in the United States and there’s one instance of him saying something racist or acting in a racist way, we gotta whip these white cops in the face. Not ‘cause they’re white — because they’re racist. We gotta say, “Yo, gimme that badge and gun. You outta here.” That’s the first way we stop these shootings. And the second thing we gotta do is teach these motherf—ers how to defuse these situations. I feel for the good cops out there, but these guys on the force are young and inexperienced, and they’re scared themselves. They shouldn’t be on the force in the first place.

When tragedies like the recent ones in Minnesota and Louisiana happen, the music community often rallies behind them to provide money, assistance, and awareness.

But, see that’s a problem, too. We wait until something happens and then we go and make a damn tribute record about it instead of making those same records every day. When Tupac and Biggie got shot, what did we do? We got together and we mourned and we made a record. “No more shootings.” And then two weeks after the funeral is over, we’re still back living with the same mind state that we had. People learn from repetition. So until these people start rapping about what’s real, what’s good, and what’s cool, it’s gonna happen again. It ain’t the law’s fault. The laws don’t mean s—, anyway. F— the law. We gotta change the way we live. When hip-hop first came along and said, “School is cool, dance instead of shoot, write graffiti instead of selling drugs,” there was an improvement within our communities. And once we knew there was a power and a creativity in the artistic expression of our youth. we realized music succeeds where politics and religion fails. Right now they’re trying to keep us separated so improvement don’t come. We’ve got to change all that.

Did gangsta rap do a disservice to the black community?

Not at all. Gangsta rap was just telling stories. We heard the West Coast music and went, “Oh s—, they got Crips and Bloods over there?” So it was an education. The problem occurs when what gangsta rap talks about is perceived as acceptable. The greatest gangsta rap record ever was “Mind Playing Tricks on Me.” Scarface was saying, “Now I can’t sleep. Lord, show me another way.” Now it’s all glorified. Back then you could tell your gangster story but there was a message at the end, saying, “But you young shorties don’t do that.” Now they’re not doing that no more. You could be illiterate and disrespectful with your presentation. You can disrespect women, you can go on about drug and violence, and as long as you are making money, they will put you on TV. They will give your endorsements and do business with you. They don’t want you in the room with them, but they’ll put you everywhere else.

Do you really think if the music industry started supporting positive rap, that kids listening to Gucci Mane, Lil Wayne, and Kanye would pay attention to the constructive messages?

Ice-T said to us, “Yo, Hollywood knows sex and drugs sell, but you all proved that positivity could, too.” So if they could put the same money they use to promote these negative images, ideas, and concepts behind a bunch of individuals promoting positive stuff, it may take a little longer, but it would work. And everyone would be better off.