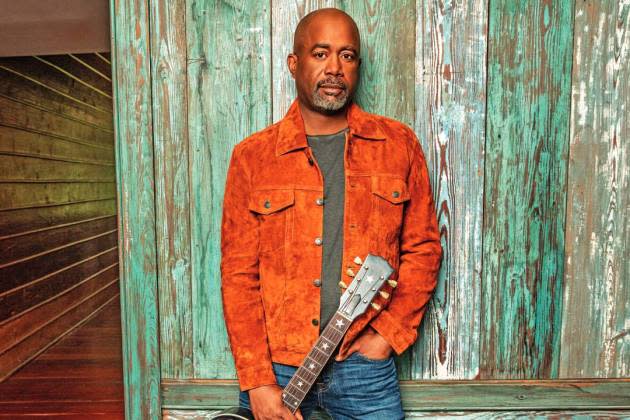

Darius Rucker Talks Hootie Legacy and Helping Country Music ‘Look More Like America’ Ahead of Walk of Fame Honor

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

“The other day, somebody told me that my voice is on the number-eight-selling album of all time and the number-three-selling country song of all time,” says Darius Rucker. “You have to pinch yourself when you hear something like that — it just blows your mind. I’m just a kid from South Carolina.”

Between Hootie & the Blowfish’s 1994 debut album, “Cracked Rear View” (21 times platinum), and his inescapable 2013 single, “Wagon Wheel” (11 times platinum), Rucker has provided the sound for two massive musical phenomena. Add in four No. 1 albums and 10 No. 1 singles on the country charts, plus three Grammy awards, and it’s pretty apparent why on Dec. 5, he’s receiving his star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame

More from Variety

Gwen Stefani Talks Fame, Family, No Doubt, and Receiving Her Star on Hollywood's Walk of Fame

John Waters Talks Trash, Divine Inspirations and Why Anti-Drag Laws Are Doomed to Fail

Marc Anthony, Who Transformed Latin Pop Music, Is Honored With Star on Hollywood Walk of Fame

“I found out on Twitter,” says Rucker with a laugh, sipping a soda in the restaurant of New York’s ritzy St. Regis Hotel. “I called my manager and said, ‘Is this real?’ I really thought they were messing with me. You don’t even let yourself dream about something like this because it’s only the biggest — the people that have done special things, and to think that they put me in that category is pretty damn cool. It validates the hard work, it validates taking chances and doing things that people said I shouldn’t do. And after being in the business for 30 years, it makes you feel like you did something right.”

It’s hard to think of another musician who reached such heights in multiple genres and shifted lanes so successfully — much less doing so while breaking down barriers in two styles that haven’t historically been too open to African American artists.

“His voice is so distinctive and he has an incredible range — both vocally and with the music he’s able to put out and still be completely authentic,” says Kane Brown, one of a generation of country artists of color who has learned from Rucker’s example. “Any time we play a show where Darius is, I’m side-stage, watching as a fan.”

For Rucker, the Walk of Fame honor offers a rare opportunity to pause and look back on a wildly unexpected career. “Usually, you’re going record to record or tour to tour, and when this happens, you get to sit down and think about the whole thing,” he says. “You think about when the band started, in a dorm at University of South Carolina, and then all the hard work, playing for seven years before you got a record deal. You think about going to Nashville and being told it was never going to work. You think about the first No. 1 [record] you ever had.

“You think about all that stuff,” he continues, “and you have to believe in fate, because one step to the left or one step to the right, and I’m not here talking to you. So you just thank God everything happened the way it did.”

With its alternative-tinged, singalong folk-rock sound, anchored by Rucker’s resonant, soul-dipped voice, “Cracked Rear View” — featuring three Top Ten singles with “Hold My Hand,” “Let Her Cry” and “Only Wanna Be with You” — was a juggernaut, the bestselling album of 1995, climbing to No. 1 five separate times over the course of the year. The singer, still awed by the staggering success, attributes Hootie’s popularity to being out of step with the times.

“Our sound was so different from what was on radio,” he says. “Grunge was such a dominant force and I think people were tired of being depressed — and we told them to hold my hand and they said OK. It’s the music and the singing and all that stuff, but it was the perfect storm at the right time.”

The follow-up, 1996’s “Fairweather Johnson,” went triple platinum but was inevitably perceived as a flop. “We knew that ‘Cracked’ was an anomaly, so we were cool with it,” says Rucker. But after a decade of diminishing returns (and a disappointing 2002 solo R&B project from Rucker), in 2008, Hootie & the Blowfish announced that the band was taking a hiatus.

“My first thought was, ‘I’m going to Nashville,’ because it was something I had talked about for so long,” says Rucker. “Don’t get me wrong — I didn’t think it would turn into this. There was nobody that looked like me on country radio when I made that first record, and it was made perfectly clear to me that they didn’t think anybody that looked like me could ever be on country radio. But I’ve never been one to do what I’m supposed to do.”

So despite his track record, when he released “Learn to Live,” he told his label, Capitol Records, that he wanted to work like he was a rookie, and proceeded to hit 110 stations on his first country radio tour. By the time the album reeled off three No. 1 singles — and he was named New Artist of the Year at the CMA Awards — Rucker had started to shift his thinking about how to reset his trajectory.

“That’s when I was like, ‘OK, now how do we make this last?,’” he says. “Because I had just come from this huge success that didn’t last, so now my whole concentration was on what we do to make sure the next record matters, and the next one. I went to the label and my management, and we just tried to do the stuff to make my career longer.”

His third album, “True Believers,” included his version of Old Crow Medicine Show’s “Wagon Wheel,” recorded with no expectation of what was coming. “I cut it just on a whim, after seeing the faculty band play it at my daughter’s talent show,” he says. “I remember sitting in the meeting about the next single, and a couple of people in the room were saying, ‘We’re not pulling out “Wagon Wheel” — radio people going, ‘That is not the song.’”

But once it took off, it became nothing less than a modern standard. “It’s an anthem in Ireland,” Rucker says, beaming and shaking his head. “I have friends all the time sending me pictures and they’re in some pub with 300 people in there singing my song.”

Last month, Rucker released “Carolyn’s Boy,” named for his late mother, who died before his music career took off. “This is definitely my most personal record,” he says. “Because of COVID, my kids going to college, I had so much to write about — every time we wrote a song, it seemed like it was more personal than the last. It’s gonna bring my fans closer to me, and at this point in my career, that’s what I need to be doing.”

A lifelong philanthropist, Rucker was recently honored with the CMA Foundation Humanitarian Award. He has advocated for over 200 charitable causes; co-chaired the capital campaign that generated $150 million to help build the new MUSC Shawn Jenkins Children’s Hospital in his hometown of Charleston, S.C.; and raised over $3.6 million for St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital through his annual Darius & Friends benefit concert and golf tournament.

“Growing up, it was just hammered into me by my mom to help,” he says. “It’s such a part of my DNA, I don’t even think about it. For me, it’s just a no-brainer, the fact that me giving my time and my voice to something can help that much. It’s still amazing to me. That’s always gonna be important to me and always be a big part of who I am.”

As the most prominent Black country artist since Charlie Pride, Rucker obviously plays a central role in the genre’s recent examinations of voice and representation. “When I came to Nashville 16 years ago, there was nobody that looked like me,” he says. “Now Kane Brown’s playing stadiums. Mickey [Guyton] sings at the Super Bowl, you got Blanco Brown and Breland and Chapel Hart and all these great bands getting record deals and getting a shot, and it’s great.”

Despite that progress, of course, many in Nashville still feel the community has a long way to go towards reaching parity in race and gender — like Maren Morris, who has loudly railed against right wing element of the country-music establishment. “I get her frustration,” says Rucker, “and I’m frustrated and upset about things, too. But I see it a different way. I’m not gonna walk away, I’m gonna try to change it, and I can’t change it from the outside. I think there’s a lot of people in the business who want it to be better and want country music to look more like America, and it’s good for me to be trying to help with that.”

Rucker, who was inducted into the Grand Ole Opry in 2012, points to the controversy over “Try That in a Small Town,” by his friend Jason Aldean, and whether the song — and maybe more so, its music video — promoted a racist message. “I see why people jumped to that conclusion,” he says, “but when I heard the song the first time, I didn’t hear racism, I heard a song about living in a small town. Conservative, sure, but not racist. But then you see the video and it’s another thing — you see that and it saddens you for a second. I talked to Jason about it, and I realize where his heart is and where it came from. And I feel bad for him — but you did it.

“I wish it wasn’t there,” he continues. “I really wish people’s parents weren’t teaching them that stuff, but they are. So I just want to be a part of the change. That’s why I’m still part of country music — I’m not going anywhere because I want to change it, I want to keep making it better. And I think that’s what me and a whole bunch of people are doing.”

Meantime, Hootie & the Blowfish just announced the 43-city “Summer Camp With Trucks” tour in 2024, the group’s first outing in five years. Rucker admits that getting back on the road with his college friends — who have consistently reunited for charity gigs over the years — didn’t work out exactly the way he had hoped.

“My mind had this fantasy that we were just gonna jump back into it,” he says, looking back at the 2019 “Group Therapy” tour (which was accompanied by “Imperfect Circle,” their first studio album in 14 years). “It’s gonna be a party every day, we’re going to take on the world, we’re gonna be best friends again. But that just didn’t happen. Everybody had their families and their own buses. That’s just the new dynamic of what we are and where everybody’s lives are. And I can’t fault them — we had never toured with our families, so I couldn’t get mad at them for that. The only time I saw those guys was onstage, and that was pretty disappointing. But when we up there every night, we were great.”

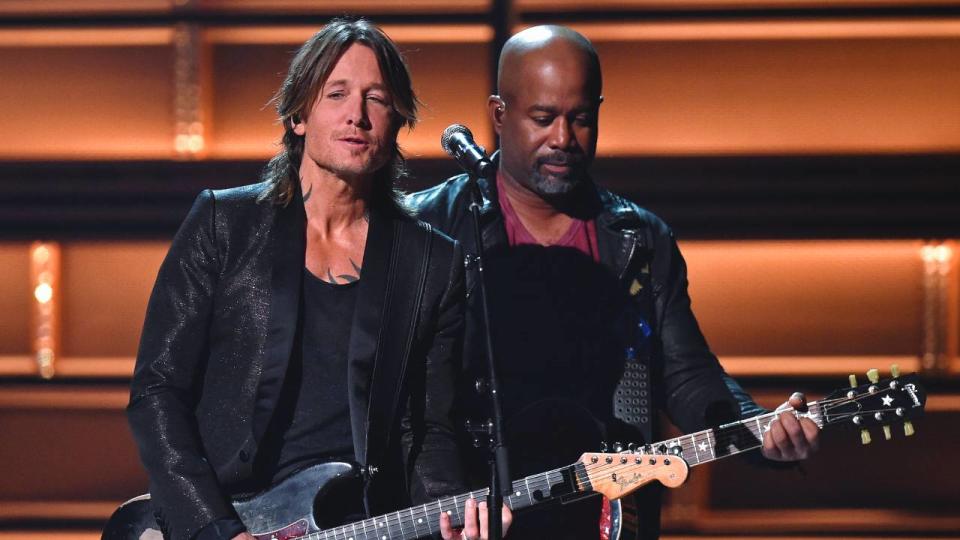

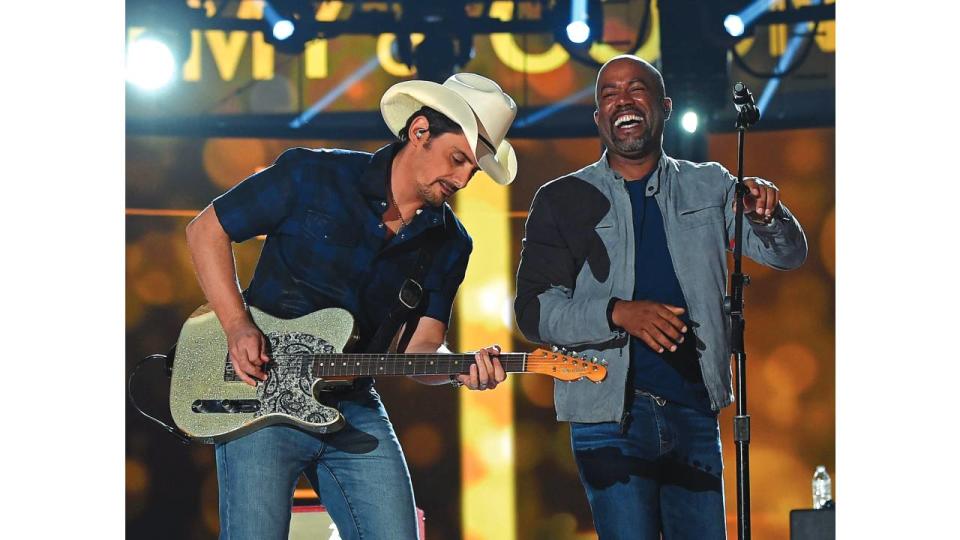

Now that more than half of his career has taken place on the country music side, Rucker has a sense of the icons he tries to model himself after. “Keith Urban, Brad Paisley — those are folks that did it right,” he says. “I think the main goal of country music is to stay humble, and those guys did that. I’m 10 years older than both of them, but those are guys that I’ve patterned myself after. Tim McGraw has been relevant since the ’90s, and not just relevant — a star, still putting out hits. Those are all good people, too, the sort of people that you want to call your friend.”

Kane Brown asserts that Rucker is holding up his end as a role model. “Darius was one of the first people in the industry to reach out and really extend himself as a mentor behind the scenes,” he says. “He has been a constant source of advice, humor and honesty and, just by being who he is, an example of how I hope to be to other artists coming up.”

Rucker is still on his grind, still putting in the everyday effort to stay on top (indeed, immediately after this interview, he headed out to do more radio promotion). “l never stopped working,” he says. “People talk about streaming and everything, but radio is still king, still how you make it in country music. You got to work with them, let them see that you still care. I think when you stop caring, they stop caring, too.

“I don’t know how much longer radio is gonna play me,” he adds. “Right now, I’m trying to try to be

one of the elder statesmen, because in country music you can do that — still go play arenas without having a hit. So I’m trying to get myself up to that point.”

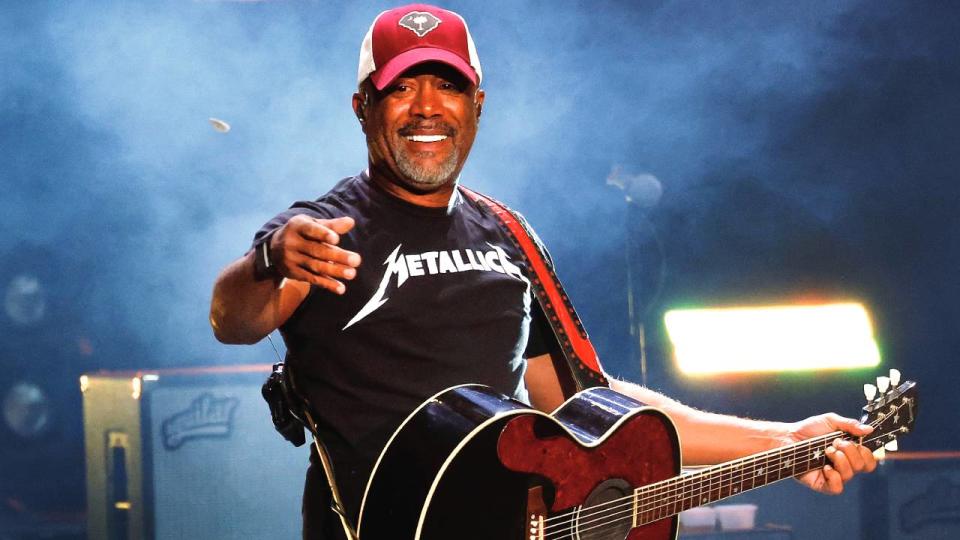

He still looks back to the fearlessness, or the innocence, that made Hootie & the Blowfish stand out all those years ago, the very uncoolness that took them to the top. “We never said, ‘Hey, we want to be R.E.M. or Metallica or Nirvana,’” he says. “We just said ‘Let’s play music and see what happens.’ We had a great ability to just let us be us.”

And from “Hold My Hand” to “Beers and Sunshine,” the No. 1 country hit from his latest album, Darius Rucker believes that connecting with an audience comes down to one thing, “The songs are what it’s all about,” he says. “If you don’t have a song, the hard work and everything doesn’t matter. At this point in my career, I just want to find the best songs, take my time, and make the records I want to make.”

TIPSHEET

WHAT: Darius Rucker receives a star on the Walk of Fame

WHEN: 11:30 A.M., Dec. 4

WHERE: 7065 Hollywood Blvd., Hollywood

Web: walkoffame.com

Best of Variety

Sign up for Variety’s Newsletter. For the latest news, follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.