The Dardenne Brothers Defend Their Right to Make Movies About Minority Experiences

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

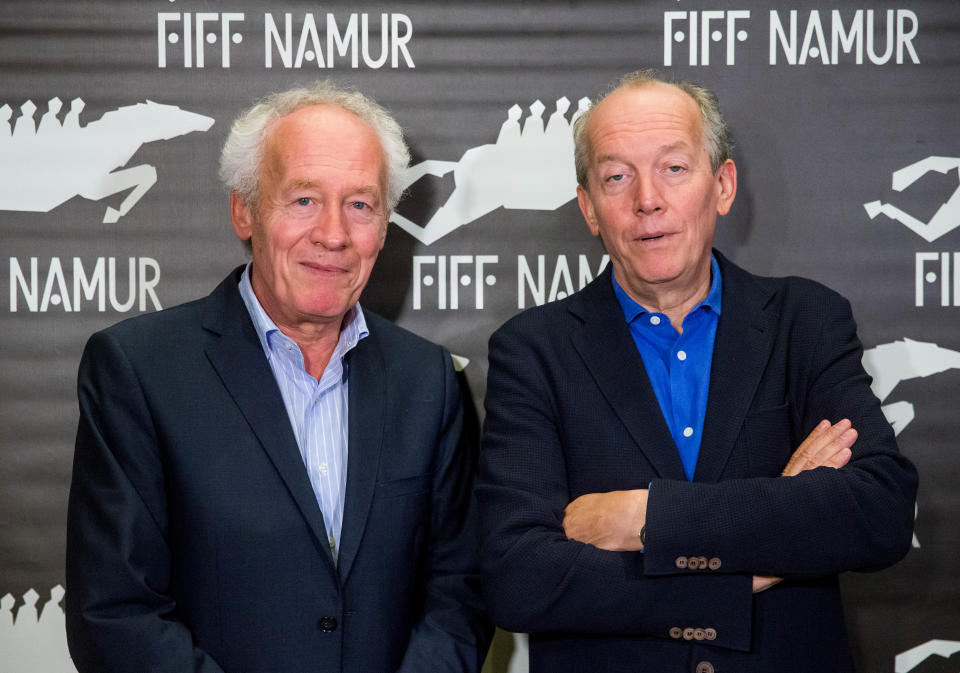

For decades, Belgian duo Jean-Pierre and Luc Dardenne have been directing movies that get inside the challenges of their protagonists. Their trademark handheld camerawork and naturalistic dramas often have a strong sociopolitical perspective, from working-class problems to immigration struggles. Their acclaimed work has yielded countless prizes, including two Palme d’Ors and other awards from Cannes, where they regularly premiere their work.

At last year’s festival, they won a special 75th anniversary prize for “Tori and Lokita,” and it’s easy to see why: The Dardennes embody the kind of the consistency of auteur filmmakers embraced by the festival and cinephiles worldwide.

More from IndieWire

“Tori and Lokita” follows a pair of young African migrants (Pablo Schils and Joely Mbundu) posing as siblings in Belgian while dealing with the older of the pair’s challenge getting residency papers. In the process, they wind up with criminals on their trail searching for money related to a drug deal. The movie is a tense and sometimes devastating look at the personal toll of the global migration crisis, a problem also at the center of the the Dardennes’ recent work, “Young Ahmed” and “The Unknown Girl.”

The Dardennes have built a career out of telling stories far removed from their own experiences. In New York to promote the U.S. release of “Tori and Lokita,” the pair justified that ongoing decision and why their thematic focus has been so consistent of late. They also shared their thoughts on theatrical distribution and the recent Oscar season.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

IndieWire: Your last three films all deal with characters impacted by the migration crisis. What inspired this focus?

Luc Dardenne: Right now, Europe is redefining itself. We still have the Dublin Agreement. If migrants arrive in Italy, then Italy is responsible for them. If they go to Sweden, they send them back to Italy. So they have a huge amount of migrants there, but right now, that’s being worked out differently. We’re going towards a globalization where it will be a shared responsibility. We’re going to divide up the migrants in terms of who takes how many. Of course, there are a few countries that are refusing, like Hungry and Poland, but it’s being worked out. The whole map in terms of how Europe is being managed will be different.

How much were you able to communicate with migrants like the ones portrayed in this film while researching the story?

Luc: For “Tori and Lokita,” we didn’t really talk to minors. First of all, it’s illegal, it’s not authorized. Even in the centers where they harbor those children, the educators and psychologists have a very hard time getting the children to actually talk about the trajectory they went through in order to get through their country of origin. So I don’t really see how we could extract from them any more than these people wanted them to reveal, because they don’t really want to talk.

For preparing the film, it really wasn’t the kids we talked to. It was really more the educators in those centers with the children that were able to give us information that would help us with the film.

Jean-Pierre Dardenne: It’s also articles that helped us in our research. Specifically, there’s a magazine for adolescents and children. There was an issue devoted to these children who come alone, unaccompanied, to another country — and the extreme solitude that they live through, and the illnesses that then are propagated by their isolation from their families. That influenced us enormously. Lokita’s panic attacks in the film are something that really happens with these kids. You know, we don’t just exist as filmmakers. We live a daily existence where we see these things happening and the stresses that arise.

There are more conversations these days, especially in the U.S., about who should be telling which stories. There’s one school of thought that stories about underrepresented people should only be told by those same people. Since you’re obviously nothing like Tori and Lokita, how do you feel about this perspective?

Jean-Pierre: What’s a shame is that this debate almost makes you feel like you’re on trial. One has to defend oneself. It’s a huge identity crisis. All discussions around this subject are banned. It impedes the possibility of transposing yourself into the life of another character. So it excludes certain artworks. It’s a bad moment to have to get past, but maybe it’ll swing back.

Luc: I think it’s true that a Black person from Africa would tell the story of “Tori and Lokita” differently than we did. A Muslim person would tell it differently than we did. But I don’t think because you’re white, you can’t tell these stories. I mean, art gives you the possibility, the capacity, to be someone else. In a certain sense, that’s the whole point. Yes, of course, if you’re a Black person who was colonized in another country, you’re going to make a different movie.

Sideshow and Janus Films

Do you feel that enough of those movies are getting made?

Luc: You know, we were speaking to our taxi driver when I was on the way to the airport. He knew that we were filmmakers. He was Congolese and he was telling us that he would love it if his daughter was a filmmaker because she could tell the story of what was going on there. He felt that no one was telling that story and that it was a really important story to tell. That’s of course true.

Jean-Pierre: The real problem is that there are [not enough] filmmakers in Africa right now and they need them. This Congolese cab driver is telling us all they’re watching is blockbusters. That’s everywhere. In 50 years, it’ll be too late. The culture is not nurturing their development.

How do you explain the potential impact of your filmmaking on audiences unfamiliar with the kind of stories you tell?

Luc: I’m heterosexual, and when I saw the film “Milk,” I experienced the suffering of someone like Harvey Milk who had to live their life as a homosexual in the time that he did it. That was major. I could identify with the various obstacles he had to deal with. Art allows people to be able to transpose themselves into another character and experience something they might not have experienced. That’s really major and very, very important. You have that possibility through film, or theater, or a painting, or dance — you have the capacity to become someone else. I don’t think that should be taken away. It’s a wonderful opportunity.

Many young directors watch your movies in film school and say they are very influenced by your filmmaking, but they’re usually referring to the camerawork more than the subject matter. How do you feel about that?

Luc: Well, on the one hand, I can understand. They’re studying the craft and it’s important for them to figure out how we do it. But I think it’s a shame. Our craft is interconnected with what we’re putting in front of the camera. With these marginalized people, we try with the camerawork to make them very present. I wish that people would focus on that a little bit more.

Jean-Pierre: The craft is important, but if you disconnect it from the essence or substance of the movie, it becomes abstract and loses its meaning.

What sort of challenges do you see for filmmaking today compared to when you first started?

Luc: It’s the platforms. We had “The Power of the Dog” in cinemas, and “Roma,” which was in the theaters. Excellent. But most of the time they either show them for three days, it’s aimed at the Oscars, and they are then diffused on Netflix or wherever. I think that we need to establish a system where these films need to be in the cinemas for three to five weeks and then be farmed out the way they are now. We’re ultimately going to have to come to an agreement between producers and cinemas so that the films will be shown for a certain amount of time.

What do you consider to be unique about the theatrical experience?

Luc: I had an experience at the cinematheque in Belgium where on Sunday mornings, I would show a film for young people and they would come with their parents. There were maybe 500 of them. It was a wonderful experience because they were discovering cinema sometimes for the first time. To have it in a cinema where you are in the dark with a big screen is a totally different experience than when we are in front of the mini-screen and walking around.

Unless you have that experience in the cinema, you can’t have the impact of internalizing the characters the way you do. When you’re on a mini-screen, you have these images that just pass through, pass through, pass through. That’s dangerous. All you’re going to end up with is images. You’re not going to end up with that deeper process that you can retain from a real cinematic experience.

Stephanie Lecocq/Epa/REX/Shutterstock

Jean-Pierre: When we were 16, we saw the movie “Mouchette,” and we were greatly impacted by what she was living through — by her suicide, her suffering, her exclusion in other people’s circumstances. I believe that experience could be the same today for somebody watching the movie under the same conditions we watched it in. It’s important to preserve that. The cinema is about the survival of humanity. It’s a place where people can have a common experience connected to a certain morality and a certain sense of aesthetics.

On a more superficial note, I wanted to ask you about the Oscar. Belgium submitted the film “Close” over yours this year. How do you feel about the Oscar submission process at this stage of your careers?

Luc: When Marion Cotillard was one of the five actresses nominated for the Oscars [for “Two Days, One Night”] we were very happy for her and the film. The fact that Belgium did not submit our film this year was understandable. There are a lot of young filmmakers coming up with different ideas. That’s fine. We don’t experience any kind of bitterness or resentment. We’re happy for them. That’s life.

Jean-Pierre: I think it’s important. I mean, not just the Oscars, but Cannes, the Cesares, et cetera. They have a role. The sweepstakes winners of the Oscars this year are having their films shown in cinemas again. It reboots them in Europe. Originally, the Oscars were created in part for that, to give a boost to pushing films to the public.

You’re both Academy members. Did you vote this year?

Luc: Yeah, my vote was for Spielberg.

Jean-Pierre:: But we didn’t see all the movies. I vote when I see the movies.

Sideshow and Janus Films releases “Tori and Lokita” in theaters on Friday, March 24.

Best of IndieWire

New Movies: Release Calendar for March 24, Plus Where to Watch the Latest Films

Martin Scorsese's Favorite Movies: 58 Films the Director Wants You to See

The 22 Best Nude Scenes in Film, from 'Shortbus' to 'Blue Velvet'

Sign up for Indiewire's Newsletter. For the latest news, follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.