Dan Rather looks back on his 70-year career: 'I didn't leave anything on the table'

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

If anyone deserves the documentary treatment, it’s Dan Rather.

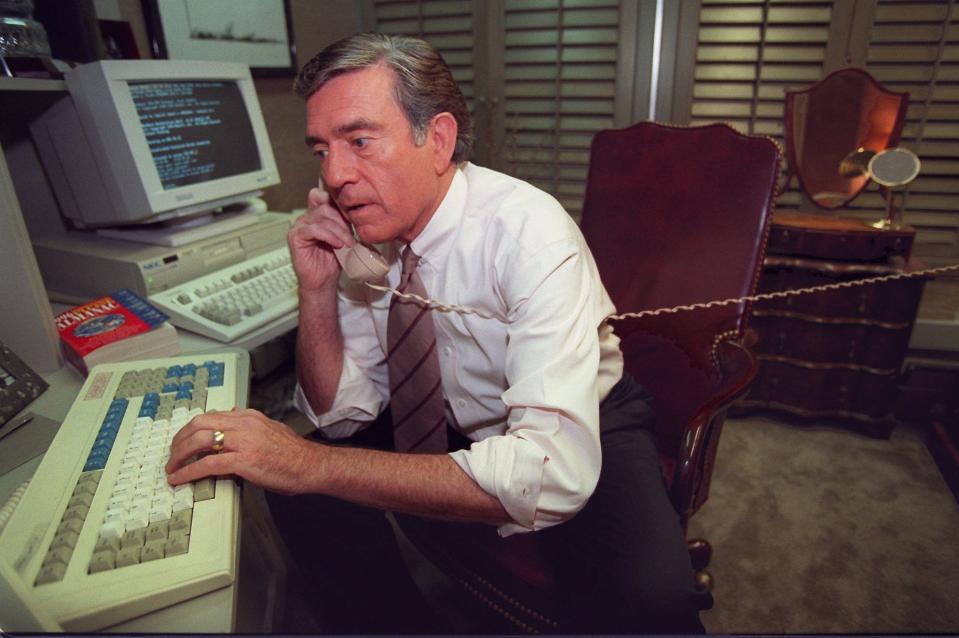

At 91, the Wharton, Texas, native is a journalism titan with more than 70 years in the industry, having covered landmark events including the JFK assassination, the Vietnam War and Watergate. He anchored “CBS Evening News” for more than two decades, leaving the network in 2005 after he reported on forged documents about George W. Bush's National Guard record that CBS failed to authenticate.

Frank Marshall’s new documentary, “Rather,” doesn’t shy away from the controversy – and Rather wouldn’t have it any other way.

“I wanted them to do an honest film,” Rather says of the project, which is seeking distribution. Ultimately, “you can argue whether you like the way I did journalism, but if you look at the record – which this documentary does – you have to give me that I thought it mattered. I cared, I gave it everything I had, and I didn't leave anything on the table.”

Ahead of the movie’s premiere on Friday at New York’s Tribeca Festival, Rather spoke to USA TODAY over Zoom about his career, legacy and the state of journalism.

Question: You’ve interviewed nearly every U.S. president since Dwight Eisenhower. You’ve witnessed firsthand some of the most defining moments in our nation’s recent history. But is there one assignment that shaped you most as a journalist early in your career?

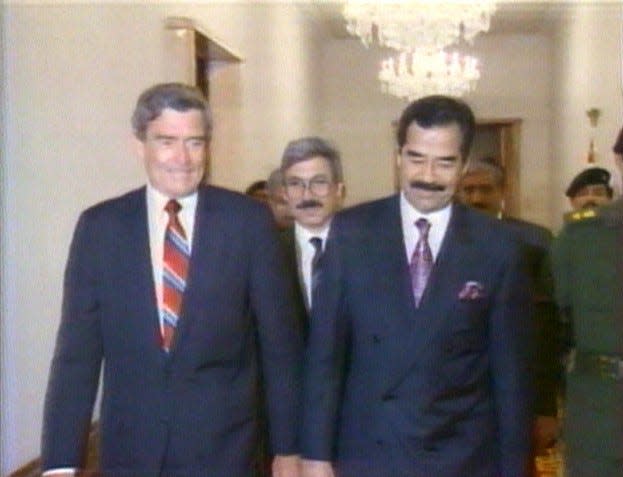

Answer: If I had to point to one, interviewing Dr. Martin Luther King and being around him changed me as a reporter. Later on, the first interview I did with Saddam Hussein was an interesting experience: alone in Baghdad Palace, several floors below ground level, talking directly one-on-one. I was glad to walk out of there all in one piece.

You’ve said before that the keys to a good interview are listening and preparation.

That is true. It’s a very tough lesson to learn because the tendency is you want to cram as many questions as you possibly can into an interview. But if you aren’t listening and you’re too eager to get on to the next question, it’s not likely to be a good interview. That’s my experience when I do an interview, whether it’s with a president or whoever.

Is there any interview that you wish you could do over?

The interview with then-Vice President George H. W. Bush, which was done in 1988, became a well-known interview and controversial. (In it, Bush lashed out after Rather confronted him about his role in the Iran-Contra affair.) If I had to do it over again, I probably wouldn’t do the interview live. We might not have been able to do the interview if we hadn’t agreed to do it live, but we did it live on the “Evening News” where we had pretty severe time restrictions. No excuses – it was what it was. But if I could do that over, I would.

On the other side, the only time I interviewed President John F. Kennedy in person was before he became president, just after he’d been nominated in 1960. I wasn't expecting to be able to interview him, but he was walking through the room, so I grabbed a microphone and got my cameraman to stand on a table. I look back, and the questions were not very good questions. I'd love a do-over on that one.

This documentary underlines how journalists have been villainized throughout history. What do you find most troubling about the level of distrust at this moment and how Donald Trump was able to sow those seeds?

Journalism has lost a lot of trust, particularly in the last few years. There are many reasons for it, one of which is that we journalists make mistakes. And every time we make a mistake, it hurts the profession. But what’s been different in recent years is there’s been one network, Fox (News), which is dedicated to the proposition that it can sell itself as a “news network” and be, in fact, a propaganda arm of a ruling party. That’s something brand new that has contributed mightily to the damage of the profession. If you agree that the purpose of journalism is to get to the truth, you have to deal with facts. And authoritarians such as the former president (believe) that facts are fungible.

But I'm an optimist, by experience and by nature. This is a very resilient country, and at the core of most people is an understanding of why it’s important to preserve (America’s) best values. So going forward, I am hopeful, but I wouldn’t mislead you: I don't go around these days thinking all day about these things. I can say with a smile that at age 91, I have another journey on my mind a lot of the time. So while I do think about journalism past, present and future, and try to do my part to help defend it and improve it, I’m not consumed by it. There was a time in my life that I was all reporting, all the time; day and night, seven days a week. Now, as the sun sinks a little bit lower, there are other things on my mind.

You once said, “Journalism is more addictive than crack cocaine. Your life can get out of balance.” Can you recall a particular moment when your job took priority and you neglected other parts of your life?

When I went into Afghanistan in 1980, after the Russians had invaded, I was told before we went in that there’s very little chance you can get out alive. I had a wife and two children, and we talked about it. And frankly, the family asked me not to go. But I went after discussing it with them: “I think this is one of the great stories of our time and this is what I do.” But looking back on it, although we did get in against all odds and did get out alive, thanks to God’s grace, I’d have a hard time defending that decision. In journalistic terms, I can rationalize it. But in personal terms – in terms of what was good for family – I’d be over the line.

You have your “Steady” newsletter and a huge following on Twitter with people of all ages. But what drives you now? What is there you’d still like to accomplish?

As long as I'm physically and mentally able to do news commentary or analysis, I’d like to. Particularly, now at this age and stage in life, any difference I make is going to be small. But what’s the purpose of being alive if you don’t have something you want to contribute? So I keep doing it because in a small way, I think what I’m doing with our newsletter makes a contribution. What we're trying to do is take events of the day and put them in historical context. I hope it’s not arrogance to say that I have some eyewitness experience, and if I can bring some new perspective through the newsletter, I want to do that. But I have no illusions: Although "Steady" does quite well, it’s nothing like sitting in the anchor chair at “CBS Evening News” or even the programs I did after I left CBS (such as "Dan Rather Reports" and "The Big Interview," both on AXS TV).

Given your own experience with the Bush documents, I’m curious how you feel about the sharp rise we’re seeing in artificial intelligence and the threat it poses to journalists? Not only can documents be fabricated, but there are all sorts of AI-generated photos and videos that get passed off as news.

Journalism of integrity in the artificial intelligence era is going to be more valuable than ever. It’s going to be a lot tougher to separate what’s true and what isn’t. I wish I were going to see deep into the artificial intelligence era – I think it'll be really interesting and really challenging for reporters. In this documentary, one of the things that comes through is the value of having reporters who will ask the tough questions and not back down. I don’t mean it in any self-congratulatory way, and I’m not saying I did it well, but I did try to ask the tough questions.

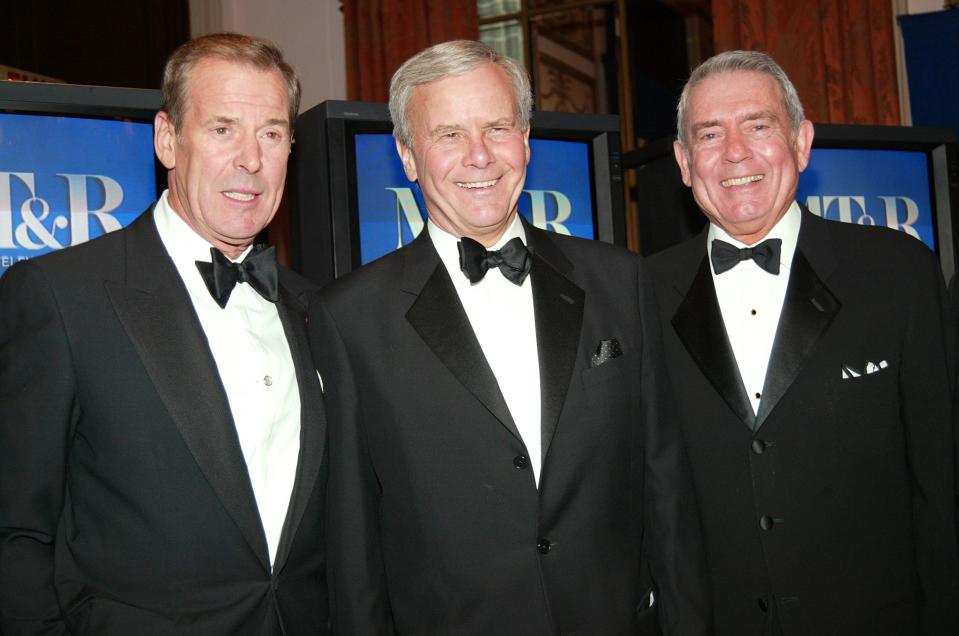

This documentary touches on your professional rivalry with Tom Brokaw and the late Peter Jennings as the “Big Three” nightly news anchors. Do you still stay in touch with Tom?

I haven't spoken to Tom recently. He's had some health issues, as have I. We were three young bulls who were competitive against one another in the beginning, but we began to respect one another and then became – at least in my own case – friends. I think they felt the same way because it was pretty rarefied air for a while. But make no mistake: Friendly as we were, we were still fiercely competitive. If I had an interview, Tom wouldn't sleep until he got one that matched it, and vice versa.

I understand that you and Walter Cronkite had your differences. Did you ever reach an understanding before his death in 2009?

I had a good conversation with him not too long before he passed on. But in some ways, this has been distorted. I never had anything but tremendous respect for Walter Cronkite. When I took the role of anchor and managing editor of the “Evening News,” there were plenty of people who told me, “It's professional suicide. You can't succeed a legend like Walter Cronkite and survive.” And I think Walter came to regret that he retired as early as he did.

He wanted to go out on top, he told me one time before I took the job. But after he’d been gone for a while, he was sorry that he left and I think in some ways, that soured the relationship. He wanted to be the only one in the Mount Rushmore of television journalism. But I do want to be explicitly clear that whatever troubles Walter had with me, I had no trouble with him.

When you first took over for Walter on the “Evening News,” you signed off your broadcasts with the word “courage.” What does that word mean to you?

It was my father’s favorite word. My mother's favorite word was “meadow,” but you'd have to agree, that's not a contender to sign off a broadcast. I had rheumatic fever when I was a child and was bedridden for a long time. And my father was very encouraging by using the word “courage” just as a one-word statement. So frankly, when I was looking for a signoff, I thought it was a pretty good idea.

And I still like it. It’s not that I think I have any courage, but I really want courage. Silently saying it to myself at certain times, including when you’re ill and life is on the line – it means something to me.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Dan Rather talks Fox News, AI and the truth about Walter Cronkite