‘I’d spy on Freddie Mercury in his dressing gown’: My life growing up in a world-famous recording studio

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

I open the front door of Rockfield Lodge to Siouxsie Sioux. She’s shiny vinyl in the Welsh sun. She’s Venus on the concrete step in thigh-high PVC boots. Her crimped black hair is soft-spiked, and I want to run my sticky fingers through it.

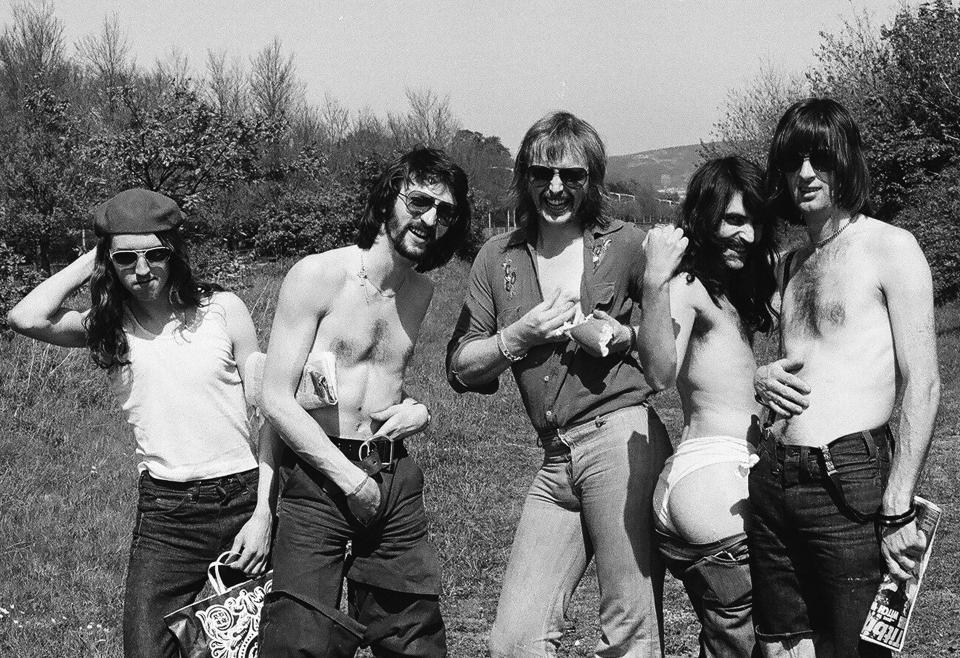

This is Rockfield Studios. It is also a farm, and I am here because my mother, Joan, is the Cordon Bleu chef. There are two kings of Rockfield: Kingsley Ward and Charles Ward. They sit at motherboards in control rooms to make magic songs in their wellies, because they also milk cows and make golden bales of hay from fields of grass with an old tractor. The queens of Rockfield are Ann and Sandra. They have five children and two dogs between them.

I am an extra because neither Kingsley nor Charles Ward is my dad. Being an extra Rockfield kid still means making tunnels through towers of hard hay bales and maybe Hawkwind dragging you into Studio Two to sing a chorus. Growing up here means swooning over The Teardrop Explodes as you serve them your mum’s Barbary duck in gooseberry sauce, then remembering your biology homework.

The Rockfield kitchen is warm and oblong, and it smells of butter and Mum’s Yves Saint Laurent. The tiles on the floor are red, the cupboards are baby-blue, and Mum calls the countertops Formica. She’s not keen on the small electric oven, but it does have four top burners that glow to spirals. Her Kenwood Chef is here, her Sabatier knife and her meat grinder. In our chalet (what she calls the converted stable) Mum keeps live shellfish in the bath, and they spit at me when I’m on the loo.

There is one door from Mum’s kitchen, and it leads to the dining room where the bands eat. They are only three red tiles away. They can hear us, and we can hear them.

I guard the door when Mum is cooking. ‘You can’t come in,’ I say to bug-eyed lead singers. They look down, confused.

If they ignore me, it’s Mum who says, Could you wait? It won’t be long. Or: Please piss off, I’m working. Or: Stop picking and wait for your meal. It depends on the musician, the band, the manager, the producer: it depends on how much the record company is paying her.

‘What do we have tonight, Joan?’ they’ll ask her from the threshold.

‘Crudités, pea and ham hock soup, boeuf en croûte, lemon cheesecake.’

‘What’s the grub, Joan?’

‘Pâté, moussaka, syllabub.’

‘What have you got then, Joan?’

‘Please get out of my kitchen!’

Mum’s kitchen is nestled in the Quadrangle, in the corner of the stable block closest to Studio One, up three steps and through a dining room where I serve David Bowie poached salmon he won’t eat (I can’t look him in the eyes, either one of them, and some nights I dream of his left, other nights I dream of his right). Here, I hoover around Pete Murphy from Bauhaus. I stay up with Bad Manners to watch A Clockwork Orange on VHS, and my mum tells me off.

Sometimes musicians knock on the door because they’re lost, or hungry, or bored, or tired, or lonely, or stoned, or can’t sleep for 10 days straight, or looking for a football, a bag of balloons for a water fight, a Frisbee; or they’re homesick, or American, or Dutch, or scared of cows, or scared of horses, or sheep; or sad, or looking for a pub, a limousine, a helicopter, a reason for why they are stranded in these Welsh fields forced to dream up songs. If my mum’s not here, I don’t know what to say, if I can say anything at all.

‘Would you like a sandwich?’

‘No thanks.’

‘Would you like a cup of tea?’

‘No thanks.’

‘Do you want to go horse riding?’

‘Not now.’

‘We can make you beans on toast?’

‘No.’

‘Tiff, will you make Julian some squash?’ Brigitte, the oldest Rockfield kid, asks.

I mix the bright-orange Quosh with tap water, as if Julian Cope from The Teardrop Explodes is a friend come to play. I look out at the fields and try to think when it all started.

Before Rockfield, I live with my mother in a vicarage in Herefordshire, at the mouth of Wales. Because she’s a chef, Mum wears pink plasters on cut fingers and the gloss of butter on her burns.

Mum decides to rent the vicarage out as a rehearsal studio, and sometimes bands live with us. They have strange names. Strange to me, at least: Black Sabbath. Horslips. Trax. I suppose the name ‘Queen’ isn’t that strange.

As Mum cooks, I sit on the stairs and watch the bands. They prance in velvet, in denim, in leather, on the zigzag patterns of the hall floor below. They march along the landing like crazed Pied Pipers with penny whistles, flutes, maracas, guitars, cow bells and castanets. The men, because they are always men, say ‘onetwoonetwotestingonetwo’ into silver ice-cream cones on silver poles that whine sharper than the bats in the barn. Mum cooks for these men, but not all of them eat.

A call came from a manager or a record label far away and Mum told me this new band, Queen, was from London, where once upon a time she had all her good times in a flat behind Harrods. She said this band sounded royal and jolly and it would be fun. When she picked me up from school the day the band arrived, she told me they’d come with a white baby grand piano strapped to a lorry and wasn’t that exciting?

One of them sleeps in my bed as Mum has moved us across the herringbone yard into the red-brick stable. He can stare out of my window at the church tower and the golden cock weathervane, at my Jimmy Osmond poster, too. The others are in the spare rooms, the attic and Mum’s four-poster bed, watching the sun rise through apple orchards. I bet it’s Queen’s fingers poking into her jars of face cream, opening the tissue of her Roger & Gallet soaps, and squeezing out all the bright-green Badedas I am only allowed two drops of. I wonder if they’ll find my hamster, Hammy, who I lost again under the stairs.

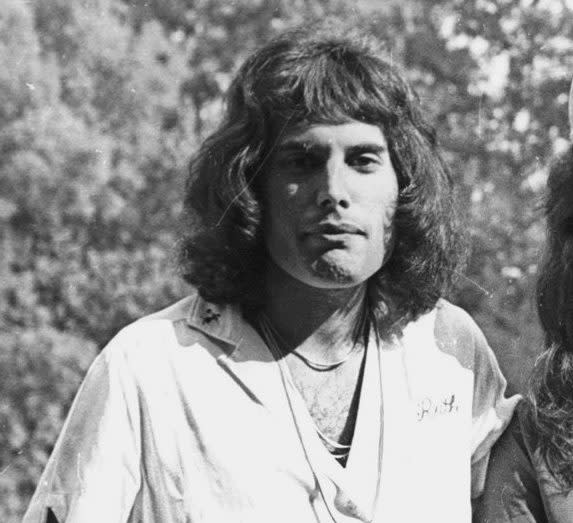

I can’t sleep. It’s almost morning, but the birds and the farmer aren’t up yet. A light comes on in the Vicarage kitchen across the herringbone yard. I get up to spy. He’s at the sink in a dressing gown covered in bright flowers. He’s making tea or coffee or wine or whatever adults do in the dark of the morning.

I wanted to listen to him play his piano and sing. Because he was in the kitchen, I knew I could sneak into the front hall without being seen, so I jumped into my dungarees and ran barefoot across the yard, through the door in the red brick wall, past the pond and over the bite of sharp gravel at the front of the house.

I’m out of breath because I’m scared. It’s dark and this doesn’t feel like my house; it smells different, there’s less dog, more man. Vox amps hum and wink red eyes at me from the mouth of our fireplace. Bedroom doors are open on the landing. I can hear men breathing, snoring.

I know I shouldn’t creep into the house this early, but it’s his fault, the singer in the dressing gown with bright flowers. He’s Fred and Freddie and his front teeth press out of his lips in a way I can’t stop looking at. He smells lovely, like sweet wood and oranges, and he’s quiet, apart from when he sings or laughs, and when he sings or laughs, he throws his head back like a thin heron gobbling a fish. In the daytime Freddie walks our wide garden with a notebook and pen, then he curls up like a no-named cat on the blue velvet sofa in the drawing room I’m not allowed in. Freddie writes while stuffed hummingbirds sparkle green inside bell jars on the scatter tables around him.

Most of the time, though, he is here under the stairs playing his white piano.

Smoke curls up. His cigarette is in the ashtray on the piano’s top and he’s gently lifting cats from the black and white keys. Plink-plonk. Freddie sits and starts to play. The piano sounds he is making are slow and sad.

Dum-dum-dum-dum, dah-dah-

Dum-dum-dum-dum, dah-dah-

I press my toes into the stair rug but the moment before I get too sad, the piano is suddenly bright and silly. Freddie is singing something about Moët and Chandon. Mum keeps a bottle in her fridge. He pauses and then sings about going to sleep, and I can’t resist.

I have a rug over my legs when I wake, but Freddie is gone.

There are things I’m absolutely not allowed to do here. Like telling my primary school I have rock stars in my house.

Yesterday I marched my class home at breaktime, ‘Along the main bloody road, Tiffany!’

I don’t know any other way.

My class ran up our drive to spy on Queen. We saw Freddie in the breakfast room, but he wasn’t singing, he was eating an egg. We hid behind the drum kit to wait for Roger, and his cymbals made a shimmering sound. The headmaster called and when Mum found us, she freaked, then drove full carloads of us back to school. The phone has been ringing with parent complaints ever since.

Yes, most of all, I can’t bother the bands.

It’s the middle of the night but the graveyard has woken me up. We are sleeping in the Vicarage because Black Sabbath are from somewhere near Birmingham and they don’t need all the rooms. I’m brave enough to get out of my bed and stand at the window. There’s a bright full moon and I see the church tower and the golden cock weathervane. They’re glowing. The graves are black teeth. There’s moon shadow, too, and a figure is dancing around the graves.

It’s screaming, ‘Aaaaaaaahhhhhhh!’ and, ‘Eeeeeeehhhhhhh!’ I blink. It could be Rumpelstiltskin. A torch beam flashes, and the lurching hawthorn hedge, the crooked branches of the witchy yews light up. I don’t know why I don’t scream; maybe it’s because the figure hasn’t got any clothes on.

The man who scythes the grave grass told me that yew trees ward off bad spirits. Their spell isn’t working tonight.

‘Haaaaaaaaaa! Eeeeeeeeeeeee!’ the bad spirit cries in the moonlight, then it falls over. ‘Ahhhhhhh, bluudy hell!’

The spirit in the shape of a man with no clothes on speaks English.

I watch it flail on its back like an upended crab. Maybe it’s not a bad spirit at all but the Green Man who’s coming to suck my blood while I’m still alive, as sure as the yew trees will suck me dry when I’m dead.

This time I do scream.

My door opens and Cleo, our Great Dane, leaps on to my bed, barking. Mum runs in to pull me away from the window; she’s probably frightened it’s open, that I’m sleep-jumping out of this house. I’m too scared to speak so I point, and she sees what I have seen: the spirit-man with no clothes on who speaks English dancing around the graves.

I burst into tears. Cleo howls from my bed.

Mum freaked. She banged on doors. ‘Sort your bloody charge out,’ she told the men. I crept out of my bedroom and on to the landing as she marched out of the open front door to the porch, the sergeant major of our vicarage. ‘Go and get him now.’

From outside I hear ‘catch him!’ shouts and laughter. The church gate creaks. A scuffle on the gravel is coming closer, then the mess of men are in the hall below me, out of breath.

‘Just keep him under control, for Chrissake!’ Mum is saying. I can smell him as well as see him: soil, whisky, man-sweat and something that tastes of metal. He’s laughing and he hasn’t found any clothes. He doesn’t look made of wood like the Green Man, but like the yews, he might have been drinking the blood and bones of the dead. Mum barks, ‘Be quiet, you silly sod, the farmer will be out soon.’

He skips over guitars, jumps on to amps. He dodges behind the drum kit as the men run after him. This spirit man looks happy in a birthday party way. He grins and laughs and jiggles. I don’t think he wants to go to bed.

‘Oz, Oz, Ozzy, come on, mate.’

Mum is standing on a chair at the foot of the staircase. She’s waiting. As he skips past her, she throws one of my grandmother’s Welsh rugs over his head. He’s suddenly quiet: a canary in a cage. The men grab him.

‘Put him to bed,’ Mum tells them. She sees my face staring down from the landing and tells me to take Cleo and go to her bedroom.

I can’t stop crying. Mum sighs but hugs me. ‘Dear me, what a fuss,’ she says. Her four-poster bed smells of beeswax and although it’s big enough for Cleo too, she is not allowed.

Mum is decisive, ‘Look, I’m telling them to leave in the morning. I cannot cope with this crap—’

A green van with gold writing turns up our drive. I hold on to a thick reed by the frozen pond and try to sound out the letters, but they swirl. The van parks up. The driver opens the back and carries out the biggest toy owl I’ve ever seen. Cleo bounds up to him and the delivery man freezes, the owl towering in his arms. Cleo barks. Mum and the band manager come out of our black and white porch.

I recognise the writing on the van now. It says ‘Harrods’. ‘What’s all this?’ Mum asks.

The Harrods man hands her the owl.

‘What in God’s name—?’

The Harrods man is now carrying two green hippos, one under each arm. I kick through the bulrush. Mum marches to the open back door of the van. I must get to her before she sends it away.

‘What the hell are all these toys?’

‘This is nothing to do with me, Joan.’ The manager is trying to calm her, shaking his head. ‘I’m telling you, Joan, I didn’t order these. It must have been Ozzy.’

‘No, this is ridiculous. There are more toys here than my daughter gets in… her whole bloody life.’

The Harrods driver sets a rocking horse down on the gravel, just as the man who danced around the graves walks out of the porch, with clothes on.

‘Ozzy, I want a word with you,’ Mum says, and he mutters something I can’t hear as the Harrods man empties the van. ‘Furious doesn’t cover it. She was too scared to go to school yesterday.’

She lets me keep the rocking horse because it’s too heavy to move and puts the rest in the attic because there is no way you’re having them all at once. A day later she tells me to choose one toy – she can’t bear my whining a second longer. I can’t decide so she hands me a dog-faced puppet with a frizz of yellow hair. ‘There, your very own rock ’n’ roll dog, Tiff. That should keep you happy. But you have to learn to make decisions, darling. Why don’t you call it “Ozzy”?’

Bands from The Vicarage who went on to record at Rockfield rave about Mum’s food, so in late 1974, when I’m six, we move there.

If Rockfield is a kingdom, the kitchen is Mum’s queendom, and like any queen she has rules for the bands:

Don’t knock at my chalet door in the middle of the night and tell me you want a bacon sandwich. There’s proper bread, cheese, Rockfield eggs, butcher sausages and bacon in the kitchen. Help yourself. I have left cocoa out on the stove.

No barging in the kitchen and chatting me up when I’m up to my elbows in duck fat. And don’t grab the cook’s tits from behind. Remember I have a burning Café Crème cigar in my hand, and I know how to use it.

Please don’t stand over the cooker, stick your fingers in a sauce and say, ‘When will it be ready?’ Also, you can’t say you ‘don’t like it’ if you have never tried ‘it’.

Attention, bands in Studio One and Studio Two, stop the food fights! Sandra and I are sick of wiping Eton mess and salmon en croûte from the studio walls. If you must, do it in the courtyard. Keep it off the motherboards, please!

Attention, bands and roadies from Studio Two! I cook for you only if your label or manager is paying. If they’re not, don’t creep up the track in the night and steal food from my fridge. If you want something, ASK. I’m generous.

No complaining about piddly things like a matchstick in the coq au vin. Yes, I’m looking at you, Wilko Johnson.

There WILL be a polite knock at the door. There WILL be a ‘hello, Joan’. There WILL be a chink of glasses, and a round of applause when the chef brings out the crêpes Suzette because this is my performance. Thank you.

And look, let’s be honest, do what you want, I can’t stop you.

The bands in Studio One can choose from a menu in advance. They sit at the pine table with benches either side. Mum says they look like schoolboys when they bunch up together; but the bands are still men, although some of them are American now. Mum feeds Be-Bop Deluxe, Hustler, Dr Feelgood, Ace, Flamin’ Groovies, Kieran White, Van der Graaf Generator and Peter Gabriel when he stayed for a night. I garnish and serve to a room full of man-noise and smoke sweet as chewed Rolos. Sometimes the room sounds of nothing but eating; perhaps they are sick of noise, perhaps they have earache, like me. When they’ve finished, they say, ‘Thank you very much, Joan,’ or sometimes nothing at all because they’re not interested in the food. ‘And why should they be?’ Mum says, but she slams plates in the sink.

American bands play Frisbee; British ones kick footballs and ask for balloons for waterbombs. Charles and Kingsley Ward and the Rockfield engineers have football matches with the bands, but they have to tell the Americans not to pick up the ball. I skip along the flagstones, keeping time to the heavy crunch of Budgie’s guitars.

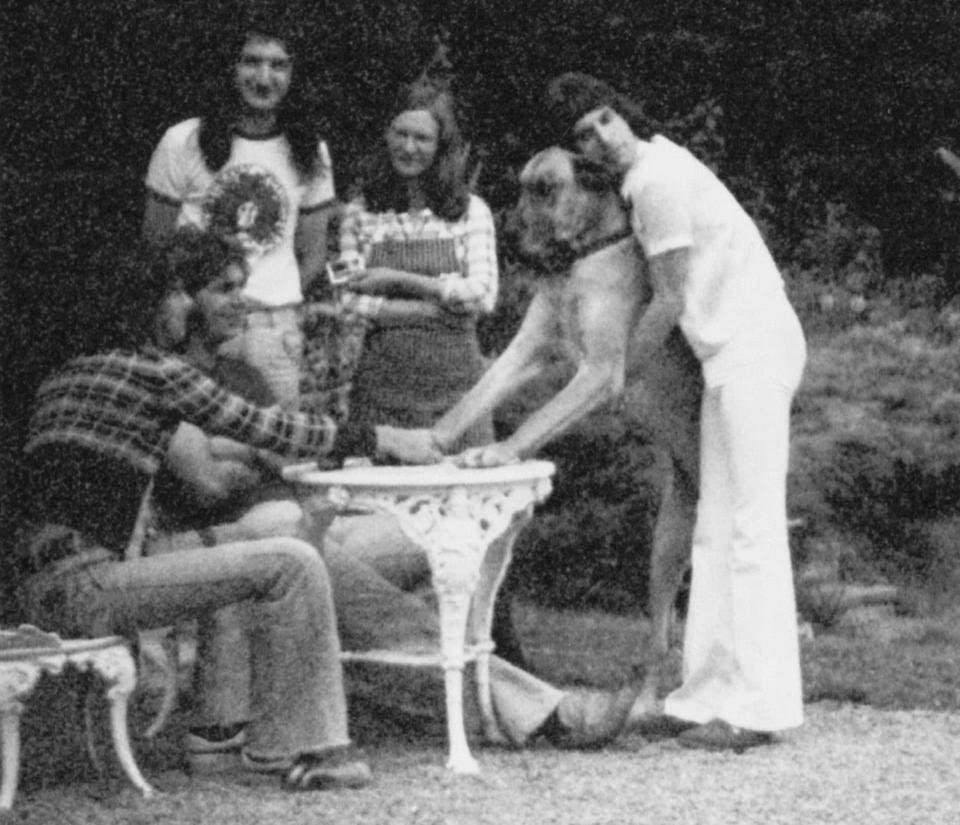

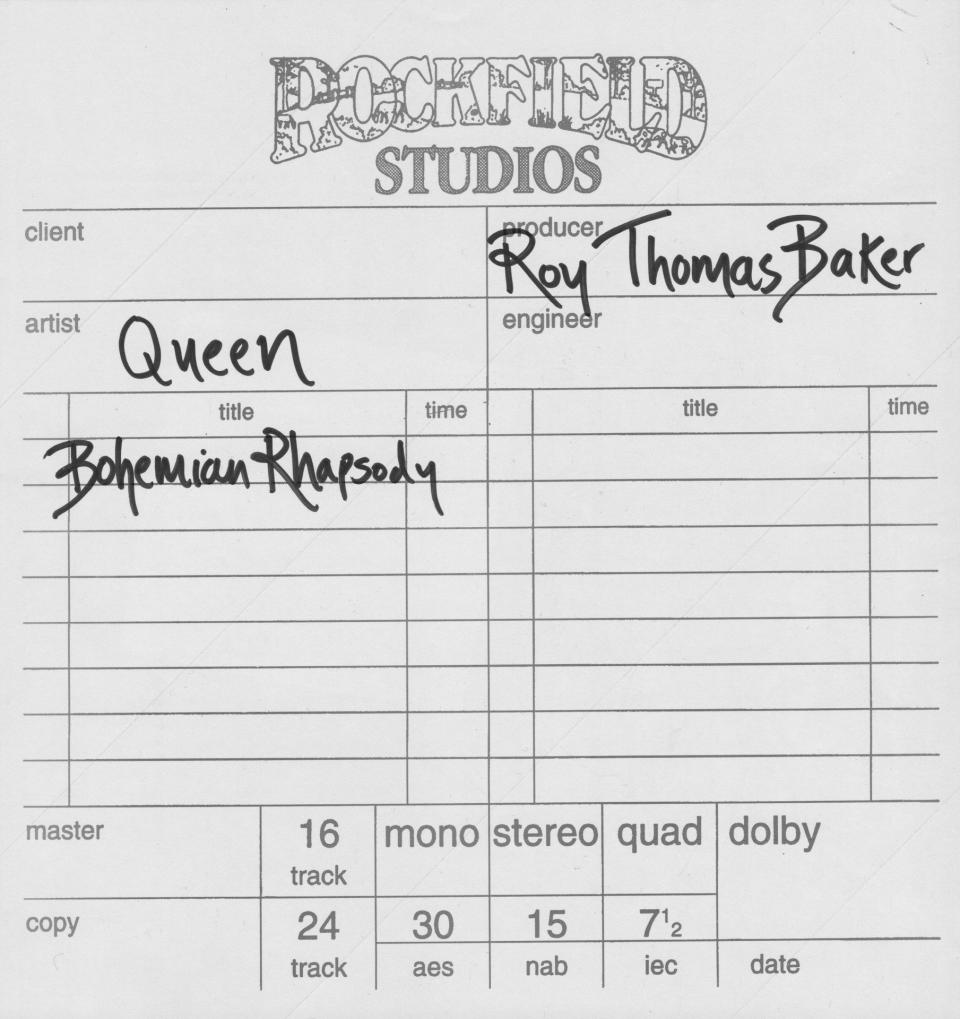

In August 1975, Queen come to record at Rockfield. It’s when the doors to Studio One open that the Galileos escape, and there is Freddie stretching in the sunlight. He squints. I wonder if he’ll go into the tack room and play the piano there: at night I hear it pour across the courtyard. Bits of Queen are always running off into the rooms around the courtyard to practise.

Galileo, the playback sings. And again: Galileo. The band say it for hours and hours and hours. Again and again. And again. Galileo Galileo.

I wait in the kitchen until Queen come to dinner. I put out the crudités and dips, then help Mum with the king prawn cocktail starter. I hear Queen’s, ‘Thank you, Joan. Thank you,’ because Queen are still very polite and Freddie toasts glasses before they eat.

It’s Christmas and I find out the Galileos and the Figaros are called Bohemian Rhapsody and it’s been number one for weeks. It’s strange seeing Queen’s heads lit up in a dark circle on Top of the Pops, and not in the yard playing Frisbee or rounders.

Abridged extract from My Family and Other Rock Stars, by Tiffany Murray, out on 16 May (Little, Brown, £22); pre-order at books.telegraph.co.uk