“I’d like to remind all the perfectionist guitar nerds to listen to Jimmy Page’s solo on In the Evening. It sounds like the guitar is falling down the stairs… It’s brilliant”: Soundgarden’s Kim Thayil dissects his “dangerous” approach to guitar playing

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Few musicians could say they shaped the ’90s quite like Kim Thayil. The Soundgarden co-founder laid the foundations for what would become known as the “Seattle sound” and later get referred to as grunge or alternative rock, paving the way for a whole movement of world-conquering noise that included the likes of Nirvana, Alice in Chains and Pearl Jam.

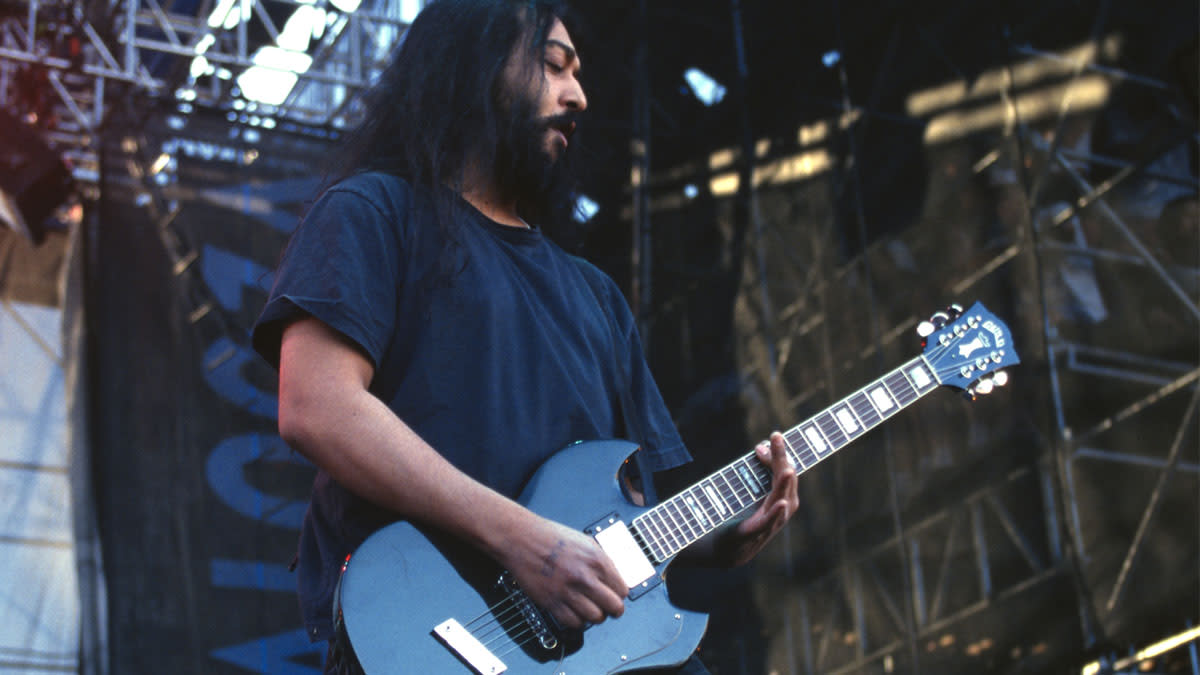

Typically seen with a black Guild S-100 electric in his hands, and on occasion its S-300 sibling, his approach to guitar has been an incredibly multifaceted one, with an easily identifiable personality to his riffs and leads that ranged from the fast and furious to the doomy and esoteric. In that regard, he was and very much still is the full package and, by proxy, an inspiration to many.

Soundgarden, who formed in 1984 and reunited in 2010 before disbanding after the tragic death of singer/guitarist Chris Cornell in 2017, rose to prominence as sonic daredevils hellbent on otherworldly experimentations – using natural harmonics and feedback to intricately detail their acid-laced hard rock. And while they embraced a number of alternate tunings, it’s arguably drop D that would end up becoming a defining feature for a lot of ’90s guitar bands.

With the sixth string detuned a whole step to allow for one-finger power chords, its sound leant to a meatier and more muscular whirlwind of noise, inspiring some of the band’s most famous tracks such as Outshined, Spoonman and Jesus Christ Pose – anthems that, it’s worth noting, wouldn’t have sounded quite the same in standard.

“I can’t say we invented or designed these tunings,” Thayil says while sipping coffee out of a white Scrabble mug on a humid summer’s day at home in Seattle. “You’d hear stories about players like Keith Richards playing in open [tuning] and maybe only using five strings instead of six. I also remember reading about Kiss dropping their guitars half a step down and realizing a lot of rock players were doing that.”

By his own admission, his first adventures in drop D felt “kinda weird.” Early on, he’d ask himself why guitarists were purposefully choosing to play an instrument that tuned incorrectly, at least in the conventional sense. And then, of course, those lightbulb moments he built a career out of started arriving thick and fast.

“When you’re learning, you start orienting toward what you are told is correct, but then you go on and liberate yourself from those constraints,” Thayil says. “Yes, there’s a common rule of thumb for tuning guitars, but there are other ways to approach it to facilitate playing or writing, or even just to change the tone. You loosen a string and get a different sort of sound… you can bend more, thanks to the extra floppiness!”

Do you remember when you first became aware of drop D?

“I was friends with Mark Arm [of Mudhoney fame] back in college. I don’t think Mudhoney were around at that point; I was in Soundgarden and he was in Green River. Buzz [Osborne] from the Melvins was hanging out a lot too. We’d listen to bands like the Young Gods, the Scientists and early Metallica at Mark’s apartment in the U District.

“One time we started talking about our favorite Sabbath songs and Buzz told us about this tuning Tony Iommi used called ‘drop-D’ that made everything sound darker and heavier. I remember going home and being like, ‘Whoa, you don’t say!’

“I started farting around and realized you could make a power chord with just one finger. Playing them really fast up and down the neck became easy. It’s funny; I remember these purists and nitwits who would write into guitar magazines saying, ‘Drop-D is cheating; you’re not really playing if you do that!’”

It’s easy to forget that trolls existed before the age of the internet.

“Yeah! I’d be sitting there wondering, “What do you think this is… Monopoly?! Is it like ‘do not pass go’ or ‘head straight to jail’ just because you don’t approve of that tuning? What do you mean it’s not a proper way of playing guitar? ‘No wonder you’re sitting there writing angry letters to a guitar magazine instead of writing songs!’

I went home from Mark’s that night and wrote Nothing to Say. I brought it to practice with Soundgarden the next day, saying, ‘Buzz showed me a Sabbath tuning and I came up with this!’

“It was such a crazy thing to say: ‘Those Seattle grunge guys are cheating because it’s easier playing in drop-D!’ I’d be thinking, ‘Thank you, and you’re right, more people should be experimenting and having fun! Oh, and by the way, we’re doing this because Black Sabbath did it. Neil Young did it. Van Halen did it. How far back are we going? Are you going to tell Eddie Van Halen he wasn’t playing guitar properly?’

“Anyway, I went home from Mark’s that night and wrote Nothing to Say. I brought it to practice with Soundgarden the next day, saying, ‘Buzz showed me a Sabbath tuning and I came up with this!’”

That must have caused quite a stir.

“Chris and our first bassist Hiro [Yamamoto] were like, 'Whoa!' with their jaws dropped open. Chris got excited and said he had just the right lyrics to fit that idea, so he ran into another room and grabbed a pen. Then he started singing this melody that had that Dio-esque thing where he’d go up high.

“At the time, heavy music was a bit like the Partridge Family through a distortion box. There was a lot of Aqua Net and Spandex! This thing was dark, psychedelic and trippy underneath Chris’ majestic voice. It generated a lot of attention from major labels and made me want to write more things like that. I loved the unorthodox way we were approaching heavy music.”

The drop-D thing became really big for us – and then other Seattle bands like Nirvana and Alice in Chains. Smashing Pumpkins were doing similar things too

It almost feels like songs like Outshined simply wouldn’t have existed in standard.

“Heavy metal and drop-D is a match made in heaven… it just works. Then Chris started dropping his sixth string even further down to B, writing songs like Rusty Cage during the Badmotorfinger era. By doing that, we could make the octave by fretting up a whole step on the next string along… which sounded cool! So messing with tunings definitely spawned a lot of stuff.

“Then Ben [Shepherd, bass] came along, and he had a background in country music with some open and slide tunings. Matt [Cameron, drums] started writing stuff with weird tunings too, like Birth Ritual, which had the sixth and fifth strings detuned. We were turning each other on to different ways of thinking.

“The drop-D thing became really big for us – and then other Seattle bands like Nirvana and Alice in Chains. Smashing Pumpkins were doing similar things, too.”

What would you say are the other defining features of ’90s rock guitar?

“Feedback was a big part of the sound. One of our first recordings was Tears to Forget, and we only had eight tracks to work with, one of which was entirely dedicated to guitar feedback. Some people thought it was funny, but it sounded cool. Utilizing unorthodox techniques became a big part of our style, like playing behind the bridge or using harmonics as part of the riff as we did on Heretic.

“We weren’t just using harmonics as an effect or lead element; it was part of the actual riff. And we did that frequently – if something sounded strange, we’d usually be inclined to explore. We’d say things like, ‘Let’s write a song where the riff is just feedback,’ or ‘Let’s come up with a riff mainly using harmonics!’ In drop D it felt a lot easier to bend the strings, almost like lead players would in solos.”

It’s a very Sabbathy move!

“Yeah, Sabbath did a lot of that. That became a very distinct signature of Alice in Chains. Jerry Cantrell writes the coolest riffs with those howling, sexy bends. Listen to It Ain’t Like That and you’ll see what I mean. I fell in love with that as soon as I heard it. That became Jerry’s thing, riffing with those awesome bends.

“Nobody could bend the note the same smooth way as consistently as he could. I’d say the two signature elements of Alice in Chains’ sound was Jerry’s bent riffs as well as those vocal harmonies. And if you listen to the Nirvana song Blew from Bleach, Kurt [Cobain] was using bends as part of the riff. These were things that were probably introduced early on in the Seattle scene through us.”

Jerry Cantrell writes the coolest riffs with those howling, sexy bends... Nobody could bend the note the same smooth way as consistently as he could

You have a strong identity as a lead guitarist – mixing elements of classic rock pentatonics and more atmospheric ideas that seem to capture a moment in time.

“As for the impressionistic guitar solos, I’m definitely not a metal lead player. Those kinds of solos owe more to classical, and as far as I’m concerned, that’s ‘mom music’! It’s the kind of stuff you do to tell your parents, ‘See, I’m not just making noise, I’m not a long-haired drug-taking asshole… this is real music influenced by Paganini!’

“I feel like those really ornate and baroque-sounding passages are almost written to show other people you’re not a fuckup. Well, in that case, go play ‘real’ music. My approach has always been more like impressionism. It’s partly blurry and down to the feel. You hear a song and then it’s time for the solo, and there’s a way to attack it – whether that’s manic and chaotic or moody or sad.”

“That’s what the takeaway should be, rather than how many notes got played, where they fell and why. If that’s the question, my answer would be, ‘I don’t know; here’s a paint-by-numbers book for you!’ Of course, there are some songs where you have to write a part that’s melodic and emphasized, complementing the vocals or riff.

“But I like the idea of getting to the solo section and having things fall apart, like a car careening off the edge in a dangerous way or something really noisy and inexplicable. I like making people go, ‘What the hell is going on there?’”

Players that came after you – including Tool’s Adam Jones and Radiohead’s Jonny Greenwood – also had that esoteric approach to their leads, almost as if they were painting through their guitars.

“Totally! It is a kind of painting, just using sonic colors. Music should be evocative. There’s something one-dimensional about having the notes occur linearly and in series… it can be compelling and stand for something, making you think, ‘What an interesting series of notes and intervals.’

“But in terms of mood, you can create more emotive ideas by freeing yourself. Is the solo dark, strange, uplifting or casual? You can tap into all of these things. Adam Jones and Jonny Greenwood are beautiful examples of guitar players doing amazing service to the song, choosing sounds that are emotive and colorful.”

What do you remember about recording Black Hole Sun?

“I remember when I heard those little arpeggios in the verse sections, I thought, “This is stylistically not like me!” It sounded more like a piano part – or like little fairies and angels dancing on the head of a pin. I thought, ‘I don’t know, man… it’s too crystal.’

“Obviously, I did end up playing that part live, but the song would come in during the middle of the set when I’d already had a few beers in me. It was really shifting gears, going from playing fast and free to, ‘Uh oh, I have to play all these notes in the right place!’

“It almost felt like I had to pull up a stool, sitting there with my legs crossed. So I had some resistance to that verse part. On the recording, I think I just played the chorus parts and solos.

“Chris wanted me to do the verse, but here’s the problem… there’s a Leslie on it. If you stop, there’s no way they can punch you back in exactly where you were. It was so frustrating. Eventually I turned to Chris and said, ‘You wrote this part; you can probably get further than I can!’”

The solo seems to capture those different sides of you well; it’s frenetic and ambitious, almost shredding in places, but also abstract to a certain degree.

“I think so! I have friends who have criticized me for playing too fast. They’d say, “You play so fast – we have no idea what you’re doing… Slow down, dude!” But they’re also players who mainly like Eric Clapton, Duane Allman… that kind of stuff.

“I am a Cream fan, and on Soundgarden’s early European tours we’d play Sunshine of Your Love at the end, mainly because we’d been drinking through the show. We all loved the song, as well as the rest of Disraeli Gears. My friends who were more into soulful and blues playing definitely wanted me to slow down. I think what I do is soulful… it’s just not blues!”

It’s the 30th anniversary of Superunknown next year. Tracks like Let Me Drown and Mailman have an almost intoxicating sense of drag to them.

“Chris wrote that opening riff to Let Me Drown, and I added the harmonies. I used to like throwing in things like that because they sounded a little bit perverted. [Laughs] Matt wrote that Mailman riff. He’s very on it when it comes to tempos. It’s one of the three or four songs on the album that Chris didn’t play on.

“I was using a single-coil guitar, either a Strat or G&L, that was tuned down to whatever Matt had written it in. I believe it was standard but with the two lowest strings dropped down to C and G. We have so many songs in weird tunings. That’s why we’d tour with so many guitars – eight or nine in some cases – because every few songs we’d need to change tuning.

“It’s strange that I chose to use a single-coil guitar instead of my Guild on that one. And then on the track Superunknown I switched back to my Guild and Chris was playing his Les Paul on the verses. Fell On Black Days might have even been Chris on his Gretsch. Different songs needed different colors.”

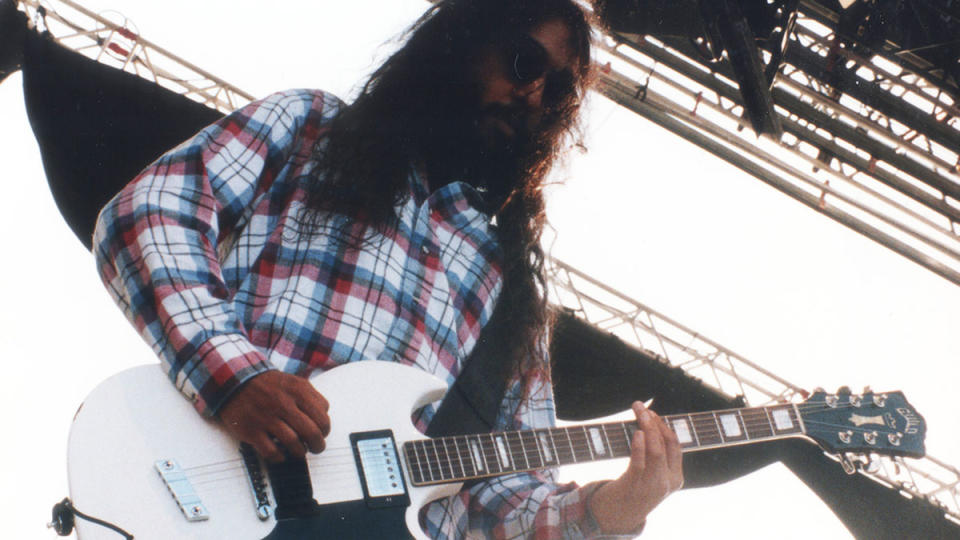

What drew you to the Guild S-100?

“I found an affordable secondhand Guild electric. It had a black finish, and I think I got it for around $235 when I was 18. The new guitars were out of my price range so I had to look at the used models. This one was in good condition and a nice color. It had peculiarities too, because of that area behind the bridge. The pickups were somewhat microphonic, so you’d get this cool feedback.

“It wouldn’t really squeal, unless you knew how, but you’d get this nice little hum. If you stood near the amp, you could move that hum around. There was also something cool about the fact it was a little lighter.

“I could make all those cool poses like Ace Frehley, even though he used a Les Paul. Kiss made guitars look like some kind of action instrument. The lighter Guild facilitated all those poses, which, admittedly, I didn’t make because I was still busy trying to learn what to play and not screw up!”

Were you still using Peavey guitar amps or had you crossed over to Mesa/Boogie by this point?

“I don’t actually know. There was a transition around then because I’d been using the Peavey VTMs around Badmotorfinger. Mostly because we endorsed them and they gave us a lot of gear for the road, which you need.

“There would be times where we’d break our amps or sometimes borrow a tube from one head and put it in another. By [1996’s] Down On the Upside, we were definitely using Boogies, but I’d also sometimes track with a Music Man head or a Fender.”

Songs like Spoonman and 4th of July also became fan favorites from this era of Soundgarden, but for very different reasons.

“Spoonman was crunchy and visceral. It had that percussive sort of feel, with Matt directing that heaviness. 4th of July was not as percussive, but it had more of a droney kind of element that relied more on ambience. It was a tough song to record because of the tuning.

“We had to use really heavy strings that would interfere with how I liked how to play, in terms of bending and finger vibrato. Heavier strings are a bit tougher, but they are able to hold the tuning better.

“Looser strings dropped down go sharp when you squeeze the neck too hard. It was a tough one to record; you’d think you got the take and then listen back to discover the guitars were slightly out.”

Looking back now, which songs are you most proud of?

“My answer changes every time I’m asked. 4th of July has this melodic lead that I doubled an octave up. It sounds very wilting and melancholic; there’s something about it that’s really sympathetic and sad, especially against the doomy riff. It could have been more chaotic and more recognizable as me throwing a bunch of paint against a wall… or shit, as the case may be. But it required something like that – a written lead in context of the song.

“Then there’s Like Suicide, which has a frenetic sort of chaos with a sense of melody, too. A lot of my solos are like that: a combination of punching in and Frankensteining different takes. I was tapping into the lyrics and sadness of the song, which has a Beatles-y Dear Prudence vibe. When the solo comes in, it’s not crying but rather shrieking and wailing. It’s like this inconsolable outburst of tears.”

Which players do you think impacted you most – and in what ways?

“I’d like to remind all the perfectionist guitar nerds reading this to listen to Jimmy Page’s solo on [Led Zeppelin’s] In the Evening. It sounds like the guitar is falling down the stairs… It’s brilliant. I remember people writing about it in the late ’70s asking, ‘Did he mean to fuck up there?’ And I’d be thinking, ‘It’s just cool!’

“The same goes for Jimi Hendrix with all that feedback. He was always pushing himself and making people ask, ‘Why did he choose to go there?!’ He wouldn’t play things the same way every time because it came from his heart, not the chart or some textbook. He was living it, thinking it and feeling it. Feedback was all over the place. It was part of the passion and intensity… and a lot of that fed into what I was trying to do!”