Crossroads of a career: Joe Pantoliano returns to his NJ hometown

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Ah, the scene of the crime.

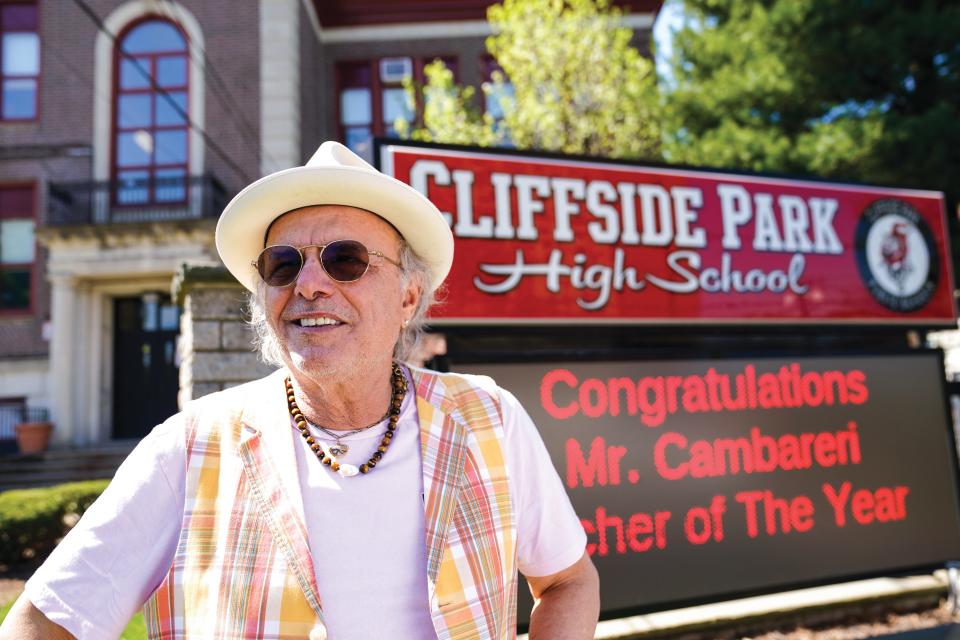

Figuratively speaking, that is. The place where Joe Pantoliano first realized he was going to be an actor. The auditorium of Cliffside Park High School. Where he has now returned, 53 years after he graduated.

"All I remember is how much fun it was," said Pantoliano, leaning back among the orchestra seats where his first audience was wowed by his performance in "Up the Down Staircase." Senior class play. February, 1970.

"The other thing I remember is, this was the only time I was ever told I could do something well," he said. "The only time I ever got a compliment."

While "Joey Pants" has played a fair number of bad guys in his 50-year career, the only crime in this particular case was to steal the show — something he's been doing on a regular basis ever since, in movies like "Memento," "The Fugitive," "The Goonies," "Empire of the Sun," in the "Matrix" and "Bad Boys" franchises, on TV in "M*A*S*H," "L.A. Law" and "The Sopranos," and on stage in "Frankie and Johnny in the Clair de Lune," and now "Rock & Roll Man" (at New World Stages, opening is June 21).

In this jukebox musical based on the life of pioneer rock-and-roll DJ Alan Freed (played by Wyckoff native Constantine Maroulis), Pantoliano gets to play a good guy and a bad guy. He's Leo Mintz, the standup guy who helps Freed get his early start in Cleveland. He's also Morris Levy, the notorious gangster record producer who takes Freed under his wing — and skims his profits — when the DJ makes it big in New York.

Good angel, bad angel? Pantoliano doesn't see the dual role that way. In fact, he doesn't see life that way.

"The older I get, it's not good and bad," he said. "It's fair versus self-serving. And it's seeped into our politics now."

Both sides now

In his long acting career — he broke into movies in 1974, just four years after his school-play debut — Pantoliano has worked both sides of the ethical street.

He's played baddies like Ralph "Ralphie" Cifaretto in "The Sopranos," Guido the pimp in "Risky Business," and the sinister Cypher in "The Matrix." But he's just as likely to be cast as law enforcement. In "The Fugitive," he was Deputy U.S. Marshal Cosmo Renfro. In the "Bad Boys" films, he was Conrad Howard, the former police captain that Will Smith and Martin Lawrence report to.

"It’s not everyone who can play a gangster on 'The Sopranos' one minute, and voice a character on 'SpongeBob SquarePants' the next," said Steven Gorelick, executive director of the New Jersey Motion Picture and Television Commission. "Now that's versatility."

They first met in the early 1980s, when "Eddie and the Cruisers" (1983) the definitive Jersey rock-and-roll soap opera, was filming in Somers Point and other South Jersey locations. Pantoliano played band manager Doc Robbins. Gorelick has been keeping an eye on him ever since.

"Joe is Jersey all the way, and he’s had a career of remarkable duration," he said. "He’s created many memorable on-screen characters throughout the years."

Leading edge

A Pantoliano character is, typically, an edgy character. The kind he first played right here, on this stage, in 1970. Joe Ferone. The bad boy. The troublemaker in "Up the Down Staircase," Christopher Sergel's adaptation of Bel Kaufman's memoir of life in an urban high school.

The boy that Pantoliano, in many ways, was. And might have remained — but for this play.

"I got into so many fights," he said. "Somebody punches you, throws you against the wall. I never went to juvie court or anything like that. But I spent hundreds of days in detention. I can show you the room."

Not, needless to say, an ace student. But what was going on underneath, what was causing a lot of his anger and frustration — what few of his teachers knew — is that he couldn't read. Dyslexia.

"I was never diagnosed," he said. "The teachers would say, 'He's not stupid, he's lazy.' Or stupid-lazy-crazy. That's what I heard, my whole life."

He was socially-graduated — and sometimes left back — in Hoboken, where he first grew up, then in Fort Lee, then in Cliffside Park. He might have left high school as unpromisingly as he entered. Except that, in his senior year, he got the inexplicable urge to act.

Maybe it was the part. Maybe the character in "Up the Down Staircase" reminded him of someone.

"I got my sister to read the play to me," he said. "My 11-year-old sister. She helped me memorize the audition material. And in this room, I auditioned. All the kids auditioning were sitting here — you're doing it right in front of them — and I had never been on stage. Well, maybe I had, doing Irish jigs or what have you."

He aced the audition. A little too much so, it turned out. "Afterwards, the teacher, the director, said, 'Read the part of the principal.' And I fumbled through it, and the kids were giggling, and I was embarrassed, ashamed."

Reading edge

His reading problem had been unmasked. But he got the part of Joe Ferone anyway. And when he did his three performances, he got something he had barely gotten before, from anyone. Approval.

"The last performance, a matinee on a Sunday, I stood right beyond that piano on stage, and I had the spot on me," he said. "It was that speech where I was asking for forgiveness, help. And as I'm doing it, I could hear people sobbing and choking up. I can feel them, feeling me. Whatever was going on, it was a powerful feeling. A feeling I've been chasing for the last 50 years."

He'd gotten the attention of the audience. More importantly, he'd gotten the attention of his teachers. Here was a troubled kid who was worth taking trouble over. "I was the beneficiary of real guardian angels," he said.

They saw to it that he was enrolled at HP Studios in lower Manhattan (an Actors Studio offshoot, run by Viennese actor/director Herbert Berghof) where Al Pacino, Robert De Niro, Faye Dunaway and Jessica Lange had studied. And they saw to it that he got reading lessons. Though these, at a local college, got off to a rocky start, he recalls.

"They're setting up," Pantoliano recalled. "All of a sudden these business men in three-piece suits with briefcases start showing up. And I'm saying to myself, how could these guys get so far, and not know how to read? As the class progressed, we discovered they had sent us to the wrong place. We were in an Evelyn Wood speed-reading class."

Subject to recall

In the end, Pantoliano learned to read. And to act. All because his high school teachers had discovered his natural gift. The big one — the one that is key, in method-actor terms, to giving a convincing performance. "Sense Memory," it's been dubbed. "Emotional Recall." "In acting school, that's what they called the ability to relive a traumatic experience," Pantoliano said in "Asylum," his 2012 memoir. "Lucky me."

What his teachers didn't know was that Pantoliano had a trove of trauma to draw on.

His background was poor. He grew up in the hardscrabble Hoboken of "On the Waterfront," the city that Sinatra had escaped from. His mother, Mary, was volatile. On his 10th birthday, as he recounts in "Asylum," she deducted the cost of his $30 birthday party from the $45 in cash he got as a present. "You cleared $15," she insisted. One of their many knockdown, drag-out fights.

When he was around 12, his father, Dominic, moved out and his mother took up with Florie, a third cousin who was a notorious drug trafficker, one who spent 21 years of his life behind bars. "This was a guy who did very bad things," he said. But he was good for Joe. "He was the driving force that gave me permission to not be like him, not to make the mistakes he made," Pantoliano said.

Dad and common-law step-dad had a fraught relationship. At least once, they brawled in the Hoboken streets. But they also remained friends, after the woman they had both loved — Joe's mother — died in 1982. "My dad took care of Florie, he had emphysema," Pantoliano said. "When he died, my father was sobbing. Florie literally died in my father's arms."

Help from above

Complicated enough for you? This was the ooze from which Pantoliano would dredge his bits of theatrical truth. And his own feelings for his family were as complicated as the family itself.

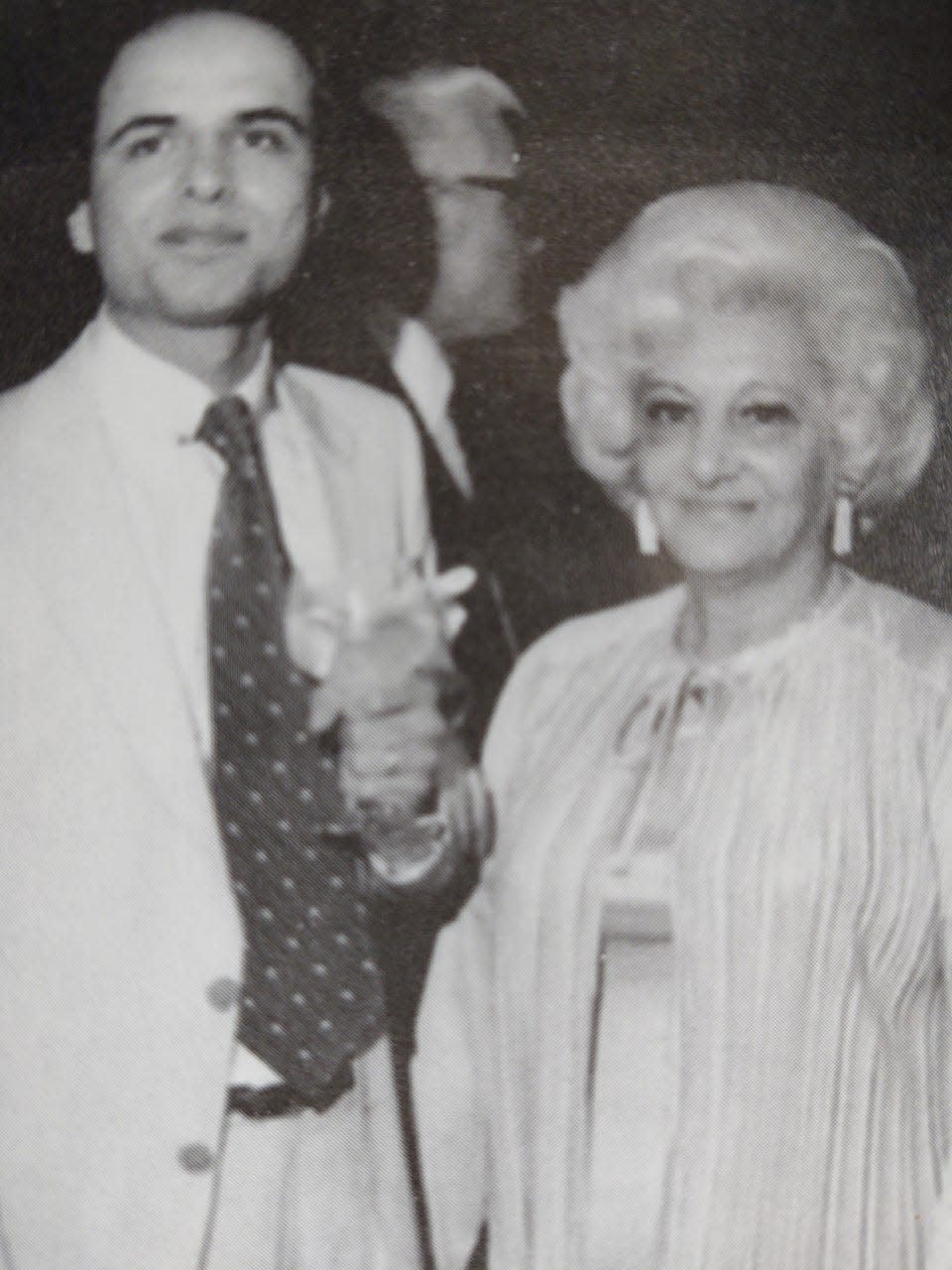

His mother, for instance. She tried, on the one hand, to discourage him from acting. "The ethnic behavior of the Southern Italians is, don't ask for too much, you don't want to be disappointed," he said. On the other hand, when she saw that he, around the age of 18, had made up his mind, she went to bat for him.

"It was a very cold day and she says, 'Come on, I need to go to Fort Lee, take me to Fort Lee,' " he recalled. "It's a four-mile drive. We turn right, we turn left, we park in front of this house. She says, 'Turn the car off, money doesn't grow on trees.' So it's 20 degrees out, I'm freezing, and my mom walks up the stairs and knocks on the door and this little old lady opens the door, looks at my mother, kisses her, hugs her, and brings her inside."

An hour later — Pantoliano was still in the car, freezing — his mother came back, got in the car, and they drove off without speaking. "Finally, she says, '[Expletive] him, we don't need him.' I said, '[Expletive] who?' 'Sinatra.' "I said, 'Who was that?' She said, 'His mother, Dolly. I know her 40 years. She said that Frank can't help you.' "

Ironically, one of Pantoliano's career breakthroughs, later on, was Angelo Maggio in the 1979 miniseries "From Here to Eternity" — the same role that was Sinatra's big comeback in the 1953 movie version.

During the run of the miniseries, Pantoliano was approached at a Hollywood screening. “I represented your predecessor for the last 30 years,” the man told him. Predecessor? It was Milton A. “Mickey” Rudin, Sinatra’s attorney. “How am I doing?” ” Pantoliano wanted to know. In the opinion of Rudin, certainly. But more — the unspoken question — in the opinion of Sinatra.

Speaking, presumably, for both, Rudin said, ‘You’re doing fine.’ “

'Dis-ease'

He was, and he wasn't.

What hadn't occurred to him, amid all the drama of his home life, was that there might be mental illness in the family. "I never thought my mom was mentally ill," he said. "I thought she was Italian-American. I thought it was a cultural thing."

It was only after an adulthood spent self-medicating — booze, pills, sex — that he got his own problem diagnosed for what it was. Depression. Probably inherited. But that, he discovered, was its own huge can of worms. Because among the places where the stigma against mental illness is most acute is Hollywood.

"When you work on a movie, you have to get a physical exam," he said. "The insurance company is going to bet that you're not going to drop dead, cause a slowdown or a stoppage. It's a very benign exam. They check your blood pressure, your heart."

One such exam, around 2004, went swimmingly for Pantoliano, until they asked what medication he was taking. Ten milligrams of Lipitor, for his family history of heart disease. And 10 milligrams of an anti-depressant.

"About four days later my lawyer calls and says, 'Yeah, we've got a problem with the insurance company,' " he said. " 'You're taking these anti-depressants. They're not going to insure you.' "

Pantoliano pointed out that he was taking the same amount of medication for his brain as his heart. "I said, 'What if I have a heart attack?' He says,' No, they'll cover that.' I said, 'So why are they discriminating against my brain? I'm taking the same dosage for two separate diseases. Why can they indemnify me for a heart disease, but not a brain disease?"

Since then, he's been outspoken about mental illness. He talks about it, and encourages others to. Anything to remove the stigma. He started a non-profit, "No Kidding? Me Too!" — the comment he most often gets, he says, when he broaches the subject — and in 2009 directed a documentary, "No Kidding! Me 2!!"

"We want to make the discussion of mental disease cool and trendy," he said. "We want kids to talk about their mental discomfort the way they would brag about having their drug dealer on speed dial."

Getting even

His own issues with "brain dis-ease," as he likes to call it, have given him insight into his roles. Ralph "Ralphie" Cifaretto, the diabolical, "Gladiator"-obsessed gangster in seasons 3 and 4 of "The Sopranos," is not a guy that Pantoliano — or any sane person — would want to emulate. "A character you hated to love," Pantoliano calls him. Yet, on some level, he gets the guy.

"Ralphie was a sociopath, he was mentally ill," said Pantoliano, who won an Emmy for the role. "He was sexually abused as a young boy. He wanted to get even. A lot of my ambition to succeed in show business was, I was going to show them. I was going to show them I wasn't stupid."

He plays a different kind of gangster in the musical "Rock & Roll Man" — although one, curiously, that figures in "The Sopranos" too. The character Hesh Rabkin, played by Jerry Adler on the HBO series, was also based on Morris Levy — the infamous owner of Roulette Records and Birdland jazz club, who died two months before he was scheduled to go to prison for extortion. Alan Freed, the DJ who popularized rock-and-roll with his radio program and all-star live revues, was just one of his many victims.

"Levy sticks him up," Pantoliano said. "Words to the effect of, 'You gotta give a little to get a little. If you want my assistance, it's gonna cost you 35 percent.' And Alan says, 'I've never given more than 20 percent.' And Morris says, 'No, you get the 35 percent.' "

Pantoliano grew up with gangsters. Understands gangsters. But he also worries about the gangster-worship that has been part of the American DNA since the days of Jesse James, and that seems to be increasingly driving our go-to-the-mattress politics. The "winner take all" mentality. He's not, he says, a "lefty" — "I'm an independent, not a Democrat, not a Republican." But some of today's politicians, he said, don't have the integrity of the wise guys he grew up with in Hoboken.

Word is bond

"I grew up with an incredibly diverse group of people in the housing projects in Hoboken," he said. "You had Black, Puerto Rican, Italian, Irish. All broke. The one thing that determined what kind of person they were is if you could depend on them. If they borrowed five bucks and paid it back. And if they didn't, it cost you five bucks to know you couldn't trust them. Done."

By contrast, some politicians today seem to have unlimited credit. Someone like Donald Trump, he said, can be exposed as a liar again and again. People still believe him.

"How many times do you have to get burned?" he said. "I used to go to Palisades Amusement Park. Ever hear of it? And you'd go to the freak show. And I remember there was a huckster out there, and he would say, 'See the 50-pound rat!' And when you get in there, you see it's not a rat at all. It's a muskrat that they put rat ears on. An imposter. You would go back and say, 'Hey, I want my nickel back, that's not an [expletive] rat.' And he'd say, 'Go away, kid, ya bother me.'"

Lesson learned. Only in the case of some of today's political hucksters, not so much. "People keep throwing nickels at these guys," Pantoliano said.

Could illiteracy be part of the problem? His old issue, back in Cliffside Park High School. On a national level, it seems to be getting worse, he said. With disturbing results for America.

"They've deconstructed the public schools," he said. "They need to keep people ignorant. Like 'The Matrix,' they need to harvest people who can't read, who are devoid of critical thinking, who will do what they're told."

Pantoliano, to be fair, was born wised-up.

That's one of the advantages — there aren't many — of growing up poor in Hoboken, Fort Lee, and Cliffside Park. It's one of the things he half-wishes he could have bequeathed his own kids: Marco, Melody, Daniella and Isabella.

"That's the greatest damage I did to my children," he said. "I didn't give them the benefits of poverty."

This article originally appeared on NorthJersey.com: Hollywood's Joe Pantoliano was helped by Bergen County 'angels'