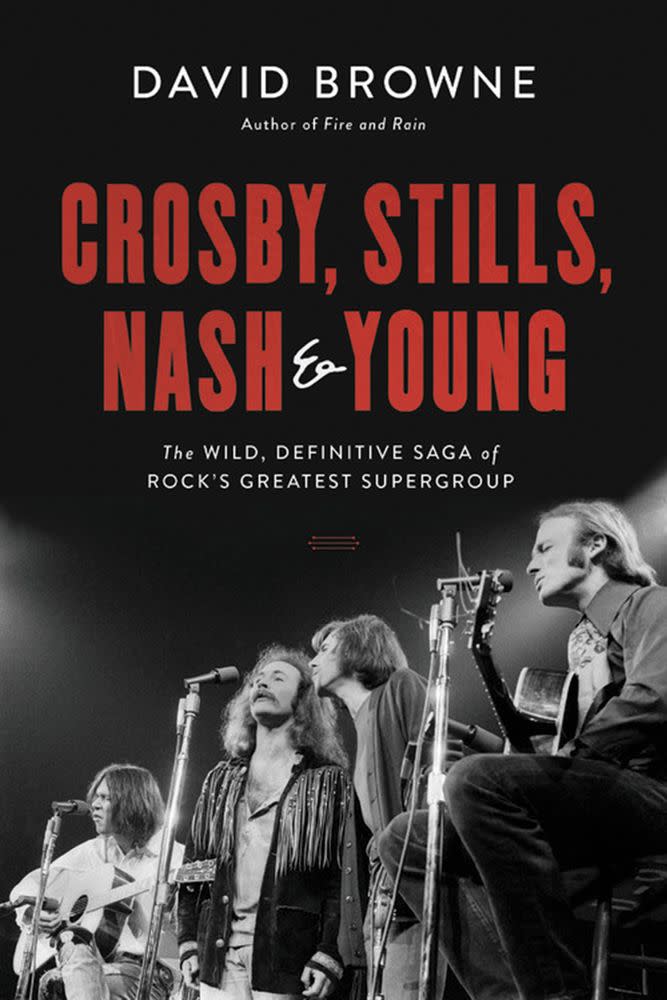

Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young biographer teases history of 'amazing dysfunctional musical family'

What’s it like documenting the history of a band whose members often have wildly differing recollections about crucial events? That is the situation which faced Rolling Stone senior writer David Browne when he began researching his new book,

(out April 2), which details the tale of rock’s most famous — and maybe most foggy-memoried — supergroup.

“They couldn’t even agree when they first got together,” says Browne. “That’s the perfect example. They still, to this day, fight over where [Crosby, Stills, and Nash] first sang together. Stills insists it was at Mama Cass’ house and Crosby-Nash absolutely insist, or they did to me, that, ‘No, he’s totally wrong, it was at Joni Mitchell’s house.’ [Laughs] Whenever they get together, or even separately, they still debate that. That really set the tone in a way of the next fifty years.”

ENTERTAINMENT WEEKLY: Why did you decide to write a book about CSN&Y?

DAVID BROWNE: I’ve been following them since I was a kid. One of my older sisters had their records. When she moved away from home, she took them all with her. It was like the opposite of Almost Famous when Zooey [Deschanel’s character] leaves her younger brother all the good records. My older sister took all the good records. So, I had to replace them, and Déjà Vu and Crosby, Stills & Nash were two of those.

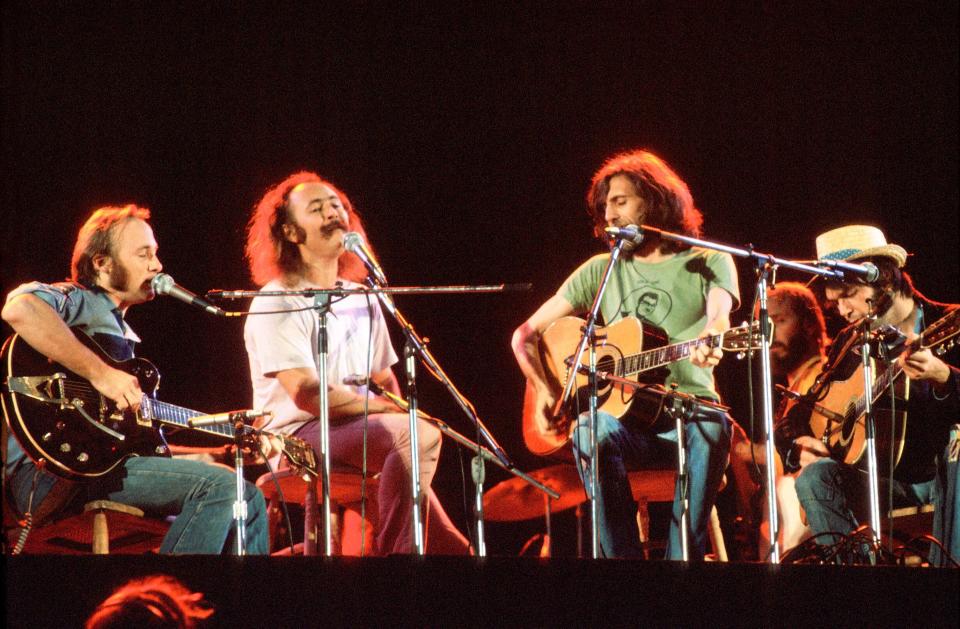

From the beginning, I really just loved the harmonies and the songs and the different personalities that emerged in the music. It was so unique. Maybe we kind of forget that after so much time. But they really were such a distinctive band and didn’t really sound like anybody else before that. At the same time, as I kept following them over the years and decades, I was also just completely caught up in what seemed like the non-stop drama.

I wrote a little bit about them in a book called

, and so when it came time to [write] another book, I realized that there really hasn’t been that much written on them in book form. It was kind of shocking to me. And combined with the 50th anniversary of their first record and Woodstock coming up this year, I felt that would probably be a perfect time to finally tackle this whole amazing dysfunctional musical family that exits to this day. [ Laughs]

As you make clear in the book, they are really the most famous rock band who aren’t really a band.

Right, right. That’s very true. That was their whole party line from the beginning. “We’re not a typical band because we’re using our names, and we’re using our names because this will allow us to do different things with different people in different combinations. We’re going to break all the rules. We’ll make solo albums if we want. We won’t even allow recording engineers in the studio to make our first record, because we want to be left alone.” Their whole thing was, “We’re going to change the rules of rock and roll.”

In a way, that has been, for better or worse, the running thread for fifty years. They seem at times to take the group aspect very seriously, and then at other times they would obviously grow frustrated with each other, or whatever else would happen, and they would go back to their original plan of dissolving and just doing things on their own. There really hasn’t been a saga quite like that, I think, in history. This dance they’ve done around each other, and with each other, in this way for 50 years, and 51 years now if you start with when CSN first sang together, is unique. And it’s had its ups and downs, for sure — musically as well.

It’s fascinating how the relationships within the band have changed over time. Every member seems to have been the best friend and the worst enemy of every other member at different points.

Right, exactly. That’s something that’s always fascinated me too. There are periods when one or the other might be steering the ship, and then there were periods when you might have Crosby and Nash versus Stills, and now we’re at a point where it seems to be Stills, Nash, and Young versus Crosby. I mean, the recurring theme is the ironic situation that Neil — the guy that was asked to join the superstar group to bolster them — has been calling the shots almost ever since. You know, if they want to do a reunion with him, they all wait for him to sign off on it. But, yes, at other times, Nash has been more in charge, and Stills was certainly in charge at the beginning. Yeah, the dynamics in that group, it really is like a family, the way at times you get along with certain family members, and other times you don’t get along with them and you gravitate maybe to someone else in the family. I think that’s very much the dynamic and I think that’s something many people perhaps relate to about them. When you see them in concert it is like crashing somebody’s Thanksgiving dinner and observing, okay what’s happening now? Who’s getting along? Who is and who isn’t getting along?

I mean, the first thing I did was just read through all these old interviews, and it just reminded me also of the way that they predated social media in the way that they would openly diss each other in interviews. [Laughs] And then they would write songs about each other. They were putting it out there in a way that you just weren’t supposed to do. You were supposed to be sort of showbiz and civil, but if they were angry with each other, it wouldn’t prevent them from expressing that.

Reading the book I found my sympathy switching between the members, depending on who seemed to be behaving worst at any given point. Did you have the same experience writing it?

Yeah, I think so. As frustrating as it must be to work with Neil, you definitely felt for him when he would say, “Okay, I’m going to do this again, I’m going to get together with these guys and do a project,” and then, after a short while, he’d realize what a mess of psychodrama he’d wandered into. They’d try to make a record and dissolve into arguments as he was watching. And you almost feel bad for Crosby during his addiction. I mean, he did it to himself, but he was just such a mess by the end there. It’s tragic, but amazing that he’s still alive after all these years. And you feel bad maybe at times even for Stills, who saw himself as the leader of the group and, boy, what a hornet’s nest he opened up when he drove over to Neil’s house and asked him to join the group. Just to wrap up the thought, there were times when I felt bad for Nash, especially in the ‘80s. He’s trying to keep this group, this business, together and trying to deal with Crosby and Stills at kind of their craziest, and still trying to get records done and trying to get them to get onstage together. It’s like, God, it’s amazing they stuck with it as long as they did sometimes. I mean, there were moments I thought, God, why didn’t they just end it in 1984? It was such a headache. But then again it was their best form of income, you know.

I was amazed to read in your book that the CSN logo was designed in the ’70s by future Saturday Night Live cast member and comedy legend Phil Hartman.

Yeah, yeah, that’s kind of mind-boggling. [Laughs] That’s just one of those crazy factoids. His older brother was their manager, and Phil was an album designer and did records for Poco and America and all those groups. He just voluntarily came up with that idea, putting a logo together for them when they reunited in ’77.

I think most people are familiar with the big CSN and CSN&Y albums. What are the underappreciated solo albums that you think people should check out?

I think the first three Stills solo albums — Stephen Stills, Stephen Stills 2, and certainly Manassas, the great double album which I think is Stills’ tour de force, really showed his incredible range of musicianship and songwriting and so on. Crosby’s If I Could Only Remember My Name has become kind of a cult classic. [It] was much derided when it came out because everybody thought it sounded like they were stoned, and it was too loose, and, of course, that’s what makes it so great now. I think Nash’s first two records, Songs for Beginners and Wild Tales, both have really terrific songs. Wind on the Water, the Crosby-Nash album from ’75, is really strong.

At the same time, it’s frustrating to hear those records to some degree, because a lot of those records have songs on them that they wanted to give to the group for the record Human Highway that [CSN&Y] kept trying to make in the mid-70s and never finished. So, you hear these songs pop up — “Carry Me,” or “First Things First,” or whatever — and you think, yeah, that’s a great song, and, boy, if that had been on that record with the others, it would have been a terrific record.

I do think one of the lesser goals of the book was to give some props to records they made after Déjà Vu. I think a lot of people tuned out because the solo [careers] weren’t as mythological as the group stuff, and maybe missed out on a bunch of really fine records that simply didn’t have the group name on them.

Related content:

Graham Nash on David Crosby: ‘I don’t want anything to do with him’

Graham Nash, Brandi Carlile, and more artists on what Joni Mitchell means to them