How to Create the Underground in Times of Surveillance: On Tim Mohr’s East German Punk History, Burning Down the Haus

Revisiting the right moments in musical history can reveal something about the world today. In two recent books, the political successes and failures of the 1980s are explored through their relationships to punk music, resulting in useful parallels to present strains of authoritarianism: Mark Andersen and Ralph Heibutzki’s We Are the Clash: Reagan, Thatcher, and the Last Stand of a Band that Mattered and Tim Mohr’s Burning Down the Haus: Punk Rock, Revolution, and the Fall of the Berlin Wall. The latter, out this week, may appear more historical in scope, but its story echoes the current challenges of creating an underground music scene in times of increased surveillance.

Burning Down the Haus deftly chronicles the formation of East Germany’s punk scene within a fragmented country under constant monitoring by a secret police agency, the Stasi. In the broadest possible strokes, the book resembles the archetypal punk narratives that have been documented across the globe: a scrappy group of young people creates their own sound and pushes back against a repressive government. In the case of Burning Down the Haus, though, the ways in which this narrative eludes expectations help it to stand out among similar histories. This isn’t simply a transposition of, say, Simon Reynolds’ post-punk history, Rip It Up and Start Again, from the UK to East Germany. This is a work that encapsulates a particular musical world but, more crucially, shows how the society around it shaped the scene in idiosyncratic ways.

Mohr's story begins with a young woman named Britta Bergmann, also known as Major. When the book opens, the year is 1977; Major is 15 and living with her family in East Berlin. Looking through a series of magazines brought over from West Berlin, Major catches sight of the Sex Pistols and is immediately fascinated by their raw aesthetic. Soon afterwards, she hears “Pretty Vacant” played on Radio Luxembourg and begins altering her clothing to echo the Sex Pistols’ look: visible stitching, a chain hanging from her jacket, and a patch emblazoned with the word “DESTROY.” Major is, in Mohr’s words, “the very first punk in East Berlin,” but she’s far from the last.

Burning Down the Haus

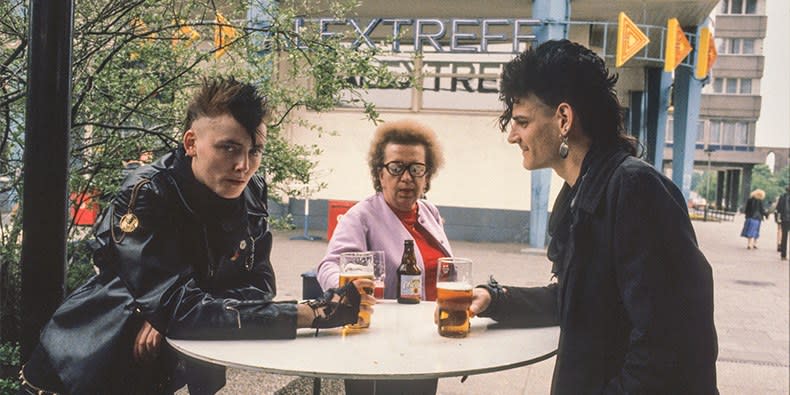

The book cover for Tim Mohr’s Burning Down the HausSome young East German rebels took up punk for the usual reasons: it reflected their worldview better than anything else available to them, right down to the difficulty it took to acquire the music they loved. But the punks of East Berlin and Leipzig differed from their counterparts in London or Los Angeles in one key way: the totalitarian government in power in East Germany could restrict its population’s access to music, penalize those without jobs, and target musicians’ ability to play music in specific venues.

Among the artists profiled in Burning Down the Haus is the long-running group Feeling B (shortened from “Feeling Berlin”), who debuted in 1983, were characterized by a drunken polka-influenced sound, and had a profitable side trade in making and reselling Western-style earrings. (Several members of Feeling B would go on to form the industrial group Rammstein.) Feeling B’s quest for an Einstufung, a license from the government to perform live music, serves as both one of the most immersive sections of Mohr’s book and as a means to delineate Feeling B from many of their peers. Many of the bands Mohr writes about opted out of this system entirely, which frequently led to legal reprisals.

In one memorable vignette, Mohr takes the reader to “the first ever semi-public punk show” in East Berlin, circa early 1981. “It was staged in the Yugoslavian embassy by a diplomat’s son who had started a band called Koks, slang for ‘cocaine,’” he writes. This is somewhat representative of the nascent punk scenes erupting across East Germany, which arose in surprisingly formal locales given the music’s attacks on the state. The Lutheran church played a significant role in finding a home base for these musicians. Mohr describes the thinking of one Halle minister, Siegfried “Siggi” Neher, who made a connection between the primal screams of punk and the fervor of the Old Testament: “grammar and order would have gone out the window; people in anguish back then would have expressed themselves the same way the punks did now.”

The punks’ frequent comparisons of the Communist authoritarianism they grappled with to the Nazi authoritarianism of an earlier generation particularly aggravated the Stasi, who saw the number of East Germans who were receptive to punk as a worrying faction within their tightly controlled society. It’s through the presence of the police, and especially the Stasi—who arrested and detained various punks, coerced musicians to inform on their bandmates, and killed one band member’s dog—that the sharpest resonances with contemporary DIY scenes come into focus. Reading Mohr’s account of the Stasi’s pervasive presence in all aspects of society, compiling dossiers on musicians and venues and doing all they could to shut them down, it’s hard not to think of certain contemporary analogues.

Liz Pelly’s article “Cut the Music,” published earlier this year by The Baffler, described an NYPD task force that is “employing a mystified style of enforcement that keeps venues and business owners living in perpetual fear.” A 2013 Slate article by Luke O’Neil discussed how undercover Boston police used false online personas as part of a department-wide effort to crack down on house shows in the city. Law enforcement isn’t the only entity using surveillance techniques to take aim at DIY spaces, either—a 2016 Washingtonian article noted that political extremists associated with the alt-right had used social media in an attempt to target venues in D.C. with the intention of shutting them down.

The methods of surveillance have changed, but the sense of DIY’s openness being used against it by authorities remains both constant and unnerving. While Mohr’s book ends on an optimistic (if slightly hyperbolic) note, tying in the efforts made by East German punks to the eventual crumbling of the Berlin Wall, reading it in light of recent events lends that victory a more bittersweet air. One is left with the sense that the next time an omnipresent and repressive government wants to crack down on an underground movement, they won’t need a intelligence organization to intimidate and surveil. They’ll have everything they need already in data trails and social media.

Tim Mohr’s Burning Down the Haus: Punk Rock, Revolution, and the Fall of the Berlin Wall is out September 11.