Country Music Hall Of Fame celebrates 50 years of Thomas Hart Benton's final mural

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

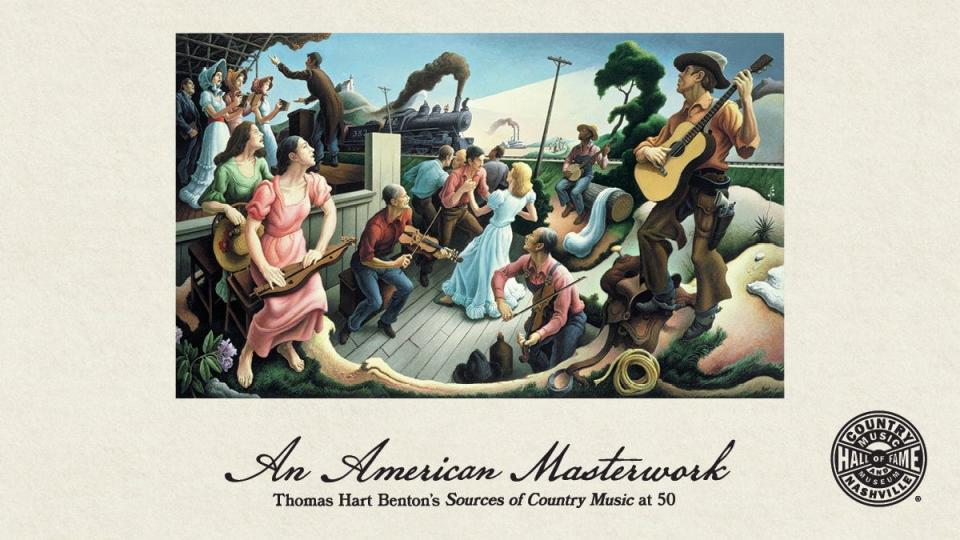

Muralist Thomas Hart Benton's "The Sources of Country Music" — the legend's final painting — celebrates its 50th year of association with the Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum (now in the museum's Hall of Fame Rotunda) via an exhibition, which is included with museum admission, open through January 2025.

The portrait's impact is not just associated with being the focal point of a room honoring 152 iconic acts and individuals related to country music's global legacy.

Upon learning the depth and scope of the artist's story and the artwork's creation and continued inspiration, the power of one of America's great, idyllic foundational showcases ever captured on a 6-by-10-foot canvas becomes apparent.

The exhibit includes Benton's sketches, drawings, preliminary paintings and his clay maquette (a three-dimensional model) created as part of Benton's process of realizing the mural. It also features a 1975 video of Benton speaking about the painting.

An unlikely connection

Months before pioneering country superstar Tex Ritter died in January 1974 — and before Benton himself passed away after finishing his final work almost precisely one year later — Ritter achieved a legacy more significant than being a star responsible for the genre's century-long entrenchment on screen, stage and in multimedia, plus being a founding member of the Country Music Association, a critical key in building the Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum's initial location on Nashville's Music Row.

Aside from splitting a bottle of Jack Daniel's in a Kansas City conversation while discussing how Benton could come out of retirement to paint the mural that would become "The Sources of Country Music," on the surface, the life parallels between a country performer and a renowned muralist seem unlikely.

However, reimagine that conversation as one between a singing cowboy from East Texas and a harmonica-playing "enemy of modernism," something different appears.

"Thomas Hart Benton's work was part of a larger belief in the capacity of sound to register and convey meaning," states author Leo G. Mazow, whose 2012 work "Thomas Hart Benton and the American Sound" places Benton's six decades of work in grander scale.

Benton's iconoclastic history

Like "outlaw" country stars of multiple eras, Benton was an iconoclastic creator and thinker who taught and inspired painter Jackson Pollock and actor Dennis Hopper.

He also never backed away from political conversations of any era.

In 1933, upon being commissioned to paint images of Indiana life for Chicago's Century of Progress exhibition, he boldly chose to include Ku Klux Klan members in full regalia alongside "regular people" to highlight "the good and bad elements of history." To wit, in 1925, in Indiana, an estimated one in three adult males were believed to be Klan members.

"History was not a scholarly study for me but a drama," wrote Benton. "I saw it not as a succession of events but as a continuous flow of action having its climax in my own immediate experience."

Two years later, as abstract expressionism and surrealism gained favor in New York and Paris, Benton was said to have "alienated both the left-leaning community of artists with his disregard for politics and what was considered his folksy style."

By World War II, Benton essentially made his home in Kansas City, Missouri, for the rest of his life.

He was so steadfast in preserving the roots of his rural upbringing and libertarian expressionism that his Pollock said Benton's traditional teachings fueled the rebellious tenor of his famed abstract works.

Did that deter Benton? Of course not.

During World War II, Benton's "The Year of Peril" series studied the threat fascism and Nazism posed to American idealism.

A musical life of 'absolute freedom'

Benton was as curious musically as he was as an artist.

He was raised on the turn-of-the-century music of the Missouri Ozarks, which, as his renown grew in the 1920s, found him for the first half of the decade, as he wrote in his 1937 autobiography, "An Artist in America," listening to "old boys, with their rheumatic arms" improvising their nasally sang work as they short-bowed the violin while playing bluegrass, folk and gospel hymns.

By the late 1920s, Benton had ascribed to a Bohemian lifestyle in New York's Greenwich Village. He led an old-time band and counted fellow free-thinking musicians Carl Ruggles and Charles Seeger as friends.

While fond of his return to Kansas City, by the 1930s, Benton and his family often spent summers vacationing on Martha's Vineyard.

It was there in 1937 that he was profiled as a notable harmonica player capable of playing compositions by Bach, Beethoven, and Schubert and transposing the music into a complex harmonica score.

About his art, the Martha's Vineyard Gazette described Benton as incapable of taking sides. "He speaks of himself as a reporter and an observer of life and claims that he never uses his work for propaganda purposes."

The story added that "Mr. Benton works under contract. He is usually given a definite assignment, which he follows or not, depending on what he finds when he gets to the scene of action. He signs only those contracts which allow him absolute freedom."

'Before there were records and stars'

By modern-era standards, Tex Ritter and Thomas Hart Benton's conversation with a bottle of Jack Daniel's and then-Tennessee Arts Commission director Norman Worrell yielded a half-million dollars to create "The Sources of Country Music."

A third of the money was received from the National Endowment for the Arts, alongside a grant from the Tennessee Arts Commission.

William Ivey, then executive director of the Country Music Foundation and the first full-time director of the Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum, recalled Benton decided that the painting "should show the roots of the music — the sources — before there were records and stars."

Benton himself, then well over 80 and in physical decline, as expected wanted something more.

"The Sources of Country Music" was to be a work "superior to the intellectual curiosities and infinitely shaded egotism of modernist aesthetics," noted the National Endowment for the Humanities.

The work is a brilliant amalgam of multi-generational influences.

The train in the distance? That's the Wabash Cannonball. Thus, it's a direct allegory to 1927's Bristol Sessions and the Carter Family, both recording "Wabash Cannonball" in 1940, plus being recorded by Ralph Peer in country music's foundational moment. Dig deeper and then there's Roy Acuff and eventually, by marriage, Carter Family member Johnny Cash, who recorded the same song in 1966.

More music: Jelly Roll, Lainey Wilson, Billy Strings and more in new Country Hall of Fame Exhibition

The barn dance features fiddlers and square dancers along the Midwest frontier. Three women read hymnals, too, highlighting the importance of country music's religious traditions.

There's also an Appalachian lap dulcimer, and Ritter himself is positioned as an armed singing cowboy with one foot in his saddle.

Yes, a banjo-playing Black man is also playing for a group of Black women across a river. This hearkens back to the instrument's West African roots four decades before Smithsonian Folkways released the "Songs of Our Native Daughters" album.

Upon announcing their new exhibition honoring Benton's work, the Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum added the following:

"Benton created a masterwork that depicts the wide-ranging cultural contributors to the musical genre. Benton died on January 19, 1975, in his Kansas City studio, having placed the finishing touches on this museum commission and while he sat evaluating his work. The completed six-foot by ten-foot mural is a synthesis of the artist, country music subject matter and the museum's educational mission."

This article originally appeared on Nashville Tennessean: Country Music Hall of Fame offers 'Sources of Country Music' exhibit