Could they be bones from the victims of the 1928 hurricane? Mystery in hands of FAU prof

Two sets of bones have sat atop a table in Meredith Ellis’ Florida Atlantic University archaeology lab for seven years.

Ellis despairs that she’ll never learn who they are. She’s got a pretty good idea how they died.

The bones are brown and shriveled and brittle and show signs they lay for years in muck —the black gold that brings life to the vast growing areas of western Palm Beach County. And sometimes brings death on a momentous scale.

They are in boxes marked “1928 Hurricane victims. Belle Glade.”

“I’m from New York,” Ellis said as we met in her Boca Raton lab last month. “I didn’t even know what it was.”

What was it? Arguably the most profound event in Palm Beach County history. And maybe America’s most under-reported disaster.

The great 1928 storm — its 95th anniversary was Sept. 16 — came ashore around West Palm Beach and slammed into Lake Okeechobee, then protected by just a low berm. The winds washed the big lake’s waters into the countryside.

The official death toll — most from drowning — is 2,500, making this the second biggest killer hurricane in American history, behind the 1900 Galveston storm. The actual number could be as high as 3,000. And that’s just in Florida. The 1928 storm is the reason there’s a giant dike.

Nearly 700 of the dead lie in a mass grave at the corner of West Palm Beach’s Tamarind Avenue and 25th Street that was anonymous for decades but now is designated by a fence and a historical marker.

A box of bones at FAU presents multitude of mysteries

And then there’s the bones at FAU.

Ellis’ lab is jammed with long tabletops scattered with bones and artifacts. But that one table is right in front of her work desk.

“I look at it every day,” she said.

Ellis doesn’t know where the bones were found, or by whom, or who gave them to FAU, or when.

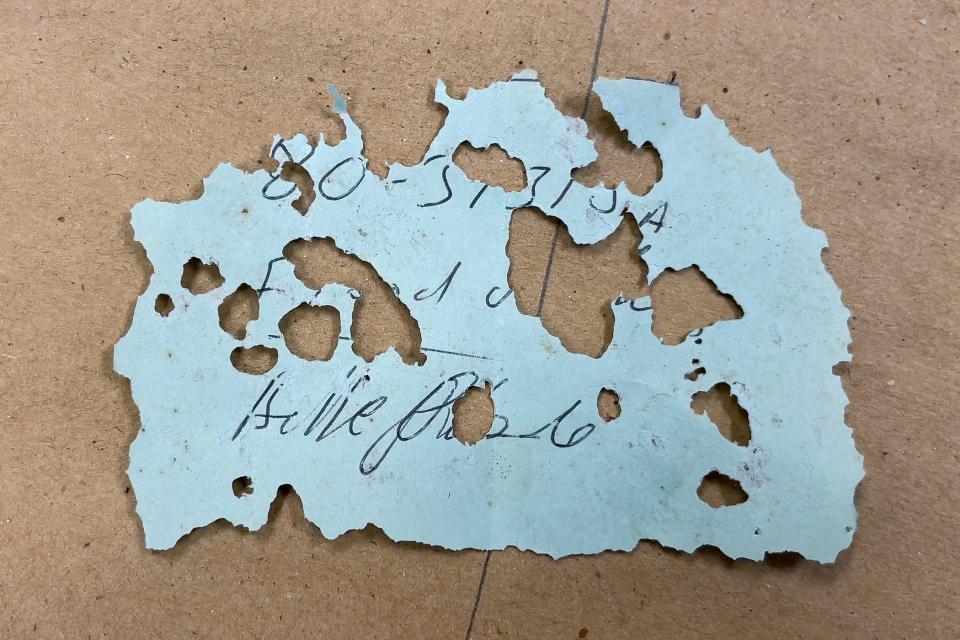

She suspects they weren’t just brought in by kids, but she does believe they came from amateurs. The way the boxes were numbered — an 80 followed by several digits — hints they were collected in 1980. But, Ellis said, “There’s a numbering system for Florida (archaeologists). This is not it.”

FAU didn't open until 1964, 36 years after the hurricane, and Ellis said the anthropology department started around the same time. Most of the faculty that was around in the early 1980s has died. And Ellis said, “the records are not great.”

Over the years, Ellis’ graduate students have helped wrestle with the mystery. She’s checked the internet and newspaper archives. And she’s talked to fellow archaeologists. Archaeology clubs. Even the Palm Beach County medical examiner. All dead ends.

She’d stumbled across the cardboard “Mott’s Sweet Cider” box, and several smaller ones, in the room behind her lab, around the time she arrived at the school in 2016.

The two skeletons had been sorted by a previous researcher.

“Someone labeled it, ‘Two people.’” Ellis said.

“These aren’t just artifacts. Bones are powerful. They’re people.”

She’s organized bones in plastic bags, clinically marked, “right arm.” “Left arm.” “Right leg.” There’s part of a skull and parts of two jawbones. Some pieces are tiny corners of somethings. Ellis, who had to learn skeletal anatomy as part of her training, said there’s part of a pelvis and a corner of a collarbone.

She thinks one’s a female in her early 20s, but there isn’t enough of a skeleton on the other to determine sex or age. She can’t tell race on either.

Small boxes contain what probably are pieces of shoe heels, along with plastic coat buttons. They are poignant remnants of lives cut short.

There are no chew marks, but she said animals could have pulled on the bodies.

More: The 30 Deadliest U.S. Mainland Hurricanes

Despite what's written on the boxes, she can’t say for sure whether they are victims of the hurricane at all. Or even from Belle Glade. But she has one big clue: Some of the bones are smeared with dried black soil.

“The muck.”

Can DNA unlock bone mystery?

The condition of the bones suggests the people were in a shallow grave. Or were in no grave, but instead drowned or suffocated in the mud and lay undisturbed for decades in a tree stand or between rows of sugar cane or peppers.

Ellis said isotope tests, and the condition of the surviving teeth, strongly suggest these people grew up in the southeast. Most of the hurricane’s victims were migrant workers from the Deep South or the Caribbean.

More: Why did 600+ black people get buried in an unmarked grave?

She said she might know more if the bones weren’t in such poor condition.

They are undergoing specialized DNA testing — specifically the teeth — but Ellis isn’t sure anything will come of that.

“It might tell us their potential ancestry,” she said.

What about all those DNA tests that advertise they can connect you with your eighth cousin in Winnipeg?

Nope, Ellis said. Those tests rely on saliva, and even if they could pull DNA from these teeth or bones, Ellis doesn’t think there’s enough.

She’s checked around for possible descendants as best she can. But if these two were migrants, they might not have any local relatives. And after the storm, whole families were dumped anonymously into mass graves or burned in gruesome pyres.

But, Ellis said, pointing at the remains, “Even if they’re not hurricane victims, they tell a story.”

And, she said, “It’s a story that might not have a clear ending. But it’s still a great story we can use to tell history.”

Retired Palm Beach Post reporter Eliot Kleinberg is author of "Black Cloud: The Deadly Hurricane of 1928."

This article originally appeared on Palm Beach Post: Belle Glade 1928 Hurricane victims? Remains of two is FAU mystery