Costume Designers Call for Pay Equity: ‘Our Work Is On the Most Important Real Estate in the Frame’

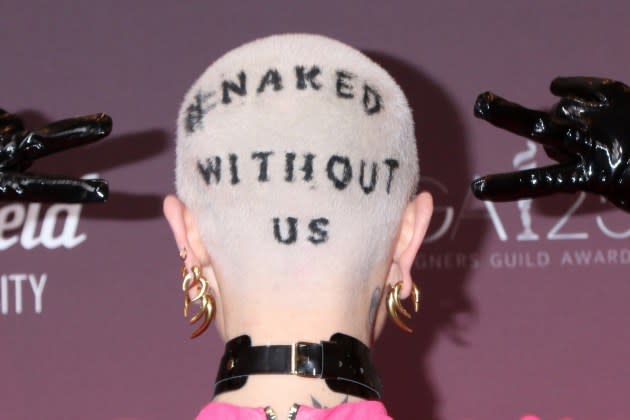

“Naked without us” was the motto for costume designers who gathered at UCLA for the Business of Costume Design Summit on Saturday.

Among the panelists were Deborah Landis, former CDG president, costume designer and founding director of the UCLA Copley Center for Design; Madeline Di Nonno, president and CEO of the Geena Davis Institute on Gender in Media; and Deirdra Govan. Costume designers, activists, journalists, researchers and guild members were among those who gathered to share their stories over the decades.

More from Variety

Costume Designers Fight for Pay Equity by Sharing Wage Discrepancies

Costume Designer Jenny Beavan's Oscar Suit Honors Guild's Pay Equity Fight

'West Side Story,' 'Cyrano,' 'Dune,' 'Coming 2 America' Among Costume Designers Guild Nominations

They discussed the ongoing discussion surrounding pay equity – a topic that is not new to the guild. For years, costume designers have been fighting for pay equity and recognition for their valuable work. Not only are they the last people off set, they are the first ones there in the morning, the costume designers argue. Their industry is comprised almost entirely of women, and they are paid far less than those in the male-dominated field of production design.

The panels were hosted by Jay Tucker, executive director of the UCLA Anderson Center for Media, Entertainment & Sports.

Here are key takeaways from the event.

‘A screenplay has no pictures‘

Costume design is powerful.

The clothes that a character wears are largely what makes them identifiable or iconic. A film or a television show starts with words and actors, and it’s the job of a costume designer to create their identity through a character’s clothes and style. As Landis explained, they aren’t creating characters, they are creating people.

“We really want the audience to lose themselves in the movie,” said Landis, whose credits include “Indiana Jones.” “Our work can disappear into the tapestry of the narrative.”

Terry Gordon, CDG president and 42-year IATSE member said, “An actor once told me, as I put him in his costume, ‘I didn’t know who I was until I put this on.’ I almost burst into tears. That’s the equivalent to getting an Oscar.”

“On Halloween, people don’t walk around with screenplays”

In addition to the artistic value that costume design brings to film and television, it also has the powerful ability to transcend the screen and make its way into the large cultural zeitgeist of entertainment and fashion–and profits.

“People wear us. We are in their closets,” said Gordon.

Researcher Evelyn Allen presented data revealing how costume design transcends the screen into people’s everyday lives. “Right now, there are about a thousand different ways to search for Euphoria outfits, and there are more than 100,000 of these searches per month,” Allen said.

Costume design leads audiences to want to emulate the characters they see on screen. Through her research, she concluded that in 2022, the Halloween costume industry hit an all-time high of $2.3 billion and that by 2030, the global market for cosplay is projected to reach $23 billion.

Except, close to none of this money is ever seen by the costume designers responsible for imagining these looks. Mona May whose credits include “Clueless,” “Enchanted” and “Romy & Michele,” said she can’t benefit from the ancillary profits that stem from her costume design.

“We’re basically for hire, and that’s about it. Everything that I think of and draw, even ideas that are not on screen, is owned by the studio,” May said.

She referred to the Rakuten commercial that aired during this year’s Super Bowl where Alicia Silverstone dressed as her “Clueless” character Cher. “Here she is in the yellow plaid suit. When you think of yellow plaid you think of ‘Clueless.’ And I wasn’t even consulted. It’s heartbreaking,” May said. Thirty years after the film’s release, a company was profiting off of May’s art, yet she never saw a dime of compensation.

‘What’s the difference between making a set and making a corset?‘

Despite being responsible for so much of screen characters’ identity, appeal and portrayal, costume designers are paid much less compared to those in other parts of production.

Much of the event’s discussion focused on the value placed on costume design with respect to other aspects of visual storytelling. On a monetary level, costume designers are at the bottom of the pay totem pole. Data presented showed that costume designers make 65 percent less than cinematographers and 28 percent less than production designers when evaluated over a 60-hour work week.

“The people who create the people should be paid the same as the people who create the place,” said Landis. “Our work is on the most important real estate in the frame, always in focus.”

“Pay is a barometer for value. We pay what we value, which means costume designers aren’t valued as much as a set designer or a DP,” said Brigitta Romanov, costume designer and CDG executive director.

In order to create more equitable wages, members of the CDG were adamant about transparency surrounding salaries and both horizontal and vertical solidarity across film industry unions.

‘When we talk about wage equity, we’re often talking about gender equity‘

The costume design industry is dominated by women.

Noreen Farrell, the executive director of Equal Rights Activists, put into perspective how gender equity affects the costume industry. She explained that the average woman will lose $1 million over the course of her career due to gender inequality, but for women in the costume industry, that number is much higher. Today, the pay gap between production designers and costume designers is about $1000 for week. That means that women costume designers are losing an average of $2 million throughout their careers.

“We are over this. We are fighting for our careers,” said Gordon. “The problem is we are 87 percent female.”

Romanov echoed these outdated biases about women in the film industry. She said that because costume design happens on a smaller scale than set designers and that larger-scale elements of a film were, in the past, left to men, the work of the female-dominated costume industry has inherently been undervalued. “We value bigger things. We value things that men do, and we have to stop it,” she said.

‘Spellcheck for bias: There’s a big difference between representation and portrayal‘

In addition to advocating against bias discrimination within the costume industry, panel members explained that costume designers are also responsible for accurate portrayals of real-life people on screen.

“I have a responsibility, not only as a costume designer but as a woman of color,” said Govan. “I’ve had the lived experience over time with scripts that are not accurate and that perpetuate stereotypes. And when you’re not that department head, you can’t really say anything. You just have to shut up and make sure the actor has their clothes.”

Govan continued, “But there was a turning point for me, not too long ago, when I really tapped into my space and my purpose as a designer, by taking on projects that would have a lasting impression. I cannot rest in my spirit taking a job that is inaccurate or inappropriate.”

Costume designers, when given adequate autonomy, have the power to turn a character into an honest and accurate representation of real people in regard to race, gender, age, disability or other factors. It’s not just about including marginalized groups on the screen, but working through stereotypes and biases when deciding how these groups will be portrayed.

Di Nonno mentioned a study at the Geena Davis Institute titled “Frail, Frumpy and Forgotten,” which concluded that female characters ages 50 and up are four times as likely as their same-age male counterparts to be depicted as frumpy, dressed in baggy clothing or in pajamas, and twice as likely as them to be depicted as unattractive or unkempt. And this doesn’t even take into consideration the issues regarding racial stereotypes.

“It’s not just the who, but the how,” Di Nonno said.

Best of Variety

Tony Predictions: Best Musical -- Four Stand Poised to Give ‘Kimberly Akimbo’ Some Competition

This 'Fast and Furious' Arcade Cabinet Allows You to Step Behind the Wheel as Dom Toretto

Sign up for Variety’s Newsletter. For the latest news, follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.