When Corporation Are People, Unions Are in Trouble

By all accounts, it’s looking like grim death for organized labor in the very near future. On Monday, the Supreme Court heard the case of Janus v. American Federation of State, County, and Municipal Employees, Council 31. At issue legally was the question of whether or not a public employee has a free speech right to withhold union dues that are deducted from his or her paycheck while still receiving the benefits for which that union has bargained. This is the third time the question has come before the Court.

The first time was in 1977, when the Court ruled in Abood v. Detroit Board of Education that such deductions were constitutional on the grounds that they prevented the obvious “free rider” problem presented by employees who refused to pay what were called “agency fees” but yet still profited from the bargaining that those fees made possible. The anti-organized labor forces in the country have had this decision in their sights ever since. The second time the question came before it, the Court ducked rather than review Abood. The third time, Antonin Scalia died mid-deliberation so the Court deadlocked at 4-4. That brings us to Monday’s oral arguments in Janus, about which Amy Howe of the invaluable SCOTUSBlog wrote the single most terrifying sentence that yet has been written about this case.

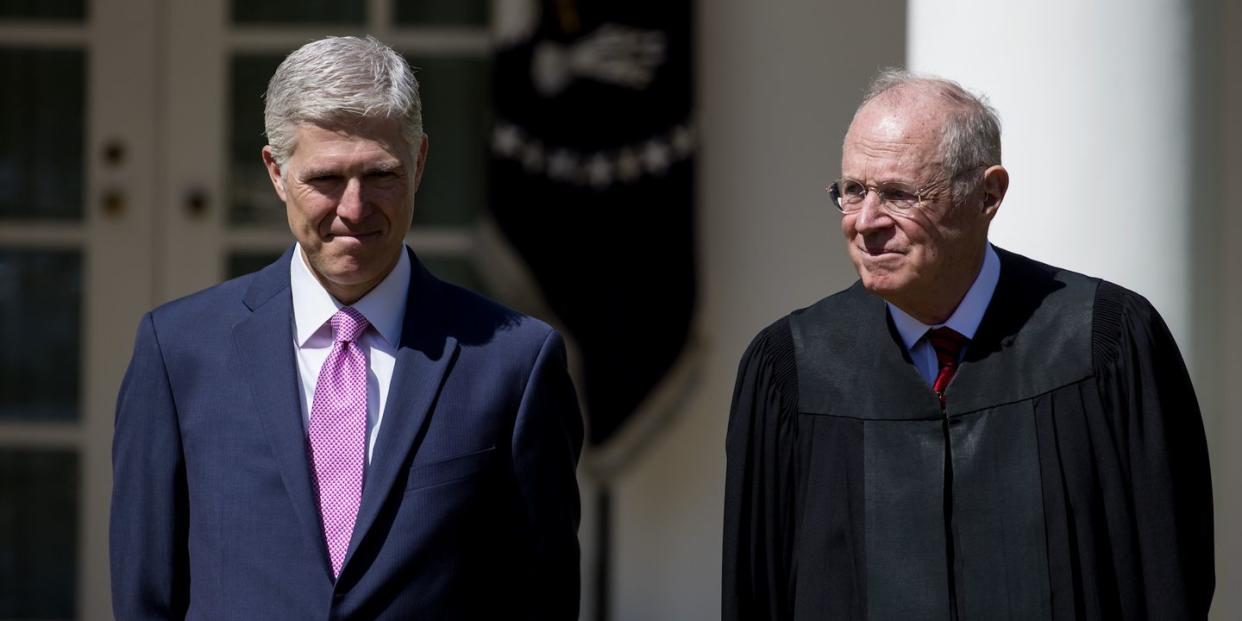

This means that the outcome in Janus’ case could hinge on the vote of the court’s newest justice, Neil Gorsuch.

The case hinges on the opinion of the guy who once argued that a company was within its rights to fire a dude who chose to survive rather than freeze to death in his broken-down big rig. I’m certainly optimistic.

Early reports from inside the Court are not promising. Ian Millhiser of ThinkProgress tweeted out that swing Justice Anthony (Weathervane) Kennedy “sounded like a Fox News host” in his questioning, which is certainly ominous. The report from Nina Totenberg of National Public Radio sounds like Millhiser was not far off.

When a decision is reached, expected in June, all eyes will be on Trump-appointed justice, Neil Gorsuch, who was uncharacteristically quiet in Monday's proceedings. He asked no questions and will likely be the deciding vote, given that the other justices split 4-to-4 in a similar case last year. The case last year was decided just after the death of the late Justice Antonin Scalia, and the balance didn't seem to change Monday. "You're basically arguing, do away with unions," Justice Sonia Sotomayor argued at one point in questioning the attorney for the National Right to Work Legal Foundation, William Messenger. On the other side, conservatives sympathized with Janus' argument that the unions are political, and someone shouldn't have to join a union they disagree with on politics. Justice Anthony Kennedy asked David Frederick, the attorney for the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees, or AFSCME, Illinois affiliate. Frederick agreed that it would. "Isn't that the end of this case?" Kennedy asked.

Kennedy, you may recall, was the swing vote in deciding that money was indeed speech in Citizens United, so we have a pretty good idea which way things are going. Also, why would Gorsuch say anything? I'd say he probably decided what he thought about this case when he was a sophomore in college.

As a former public employee, and onetime AFSCME member, I’ve really not been objective on this case from jump. But this cause - and the three cases that have been brought since Abood was decided 40 years ago - did not spring spontaneously from public employees who resent the deduction from their paychecks. As noted, the corporate class in this country, which has succeeded in shredding organized labor in the private sector, hated the notion that public employee unions - especially teachers' unions, which the corporate class particularly enjoys demonizing - still had considerable political clout. This is the end of a very long march. From The New York Times:

The case illustrates the cohesiveness with which conservative philanthropists have taken on unions in recent decades. “It’s a mistake to look at the Janus case and earlier litigation as isolated episodes,” said Alexander Hertel-Fernandez, a Columbia University political scientist who studies conservative groups. “It’s part of a multipronged, multitiered strategy.” In doing so, these donors have not just brought labor to the brink of crisis but threatened the Democratic Party as well. Amid changes in the campaign finance landscape and the decline of private-sector unions, the party and its candidates have increasingly relied on major public unions for funding, including hundreds of millions of dollars in direct and indirect spending during the 2016 presidential cycle. Those unions include the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees, whose Council 31 is the defendant in the Janus case.

And, as is often the case, some of the major victories for the corporate class were won out in the states long before this case ever got to Washington.

In 2011, Wisconsin rolled back the right of most public unions to bargain over anything other than wages and eliminated the requirement that nonmembers pay fees. The portion of unionized public-sector workers in the state plummeted from half to just over one-quarter within five years. In seeking to produce similar results nationally, conservative donors have created a symbiosis between groups aiming to overturn Supreme Court precedent favorable to unions and groups that take advantage of those rulings to drain unions of members. The Lynde and Harry Bradley Foundation of Wisconsin, which had over $800 million in assets in 2016, has funded both kinds of organizations. In a 2014 case brought by a group that had received more than $1 million in contributions from the Bradley Foundation, the Supreme Court ruled that home-care aides and other “partial-public employees” paid through Medicaid could not be forced to pay fair-share fees if they left their unions. Unions say these fees, typically about 80 percent of standard dues, are necessary to compensate them for representing nonmembers in bargaining and grievance proceedings.

This is about crippling the Democratic Party as much as it is about eliminating effective collective bargaining in the one area where such bargaining still exists, and it all depends on a guy who thinks corporations have free speech rights and another guy who believes that die-or-be-fired is a legitimate form of management-labor relationships. They know what might be coming in the midterms. They’re grabbing all they can.

You Might Also Like