When Cops Let a Serial Killer Terrorize Queer New York

One of the most telling moments of Last Call: When a Serial Killer Stalked Queer New York, the new HBO docuseries about a serial killer who terrorized gay men in the Nineties, comes when director Anthony Caronna is interviewing a pair of retired police detectives who worked the case. The interviewer asks a pretty standard wrap-up question, something along the lines of, “Is there anything you wish I had asked?” One of the detectives replies with his own question: “Why is the emphasis on the gay part?” Well, sir, it’s a film about a murderer who killed gay men. Whom he picked up at gay bars. Thereby terrifying the gay community. And yet there remains a trace of “Don’t say gay” among the mostly straight, mostly male cops here, who doth protest that they did everything in their power to crack the case as quickly as possible. The film suggests that these two factors – a queasiness about homosexuality, and a sense of justice delayed – are closely related. This context, and a high level of craft, are what elevate Last Call above the realm of a mere serial killer procedural.

Based on the book by Elon Green, the four-part Last Call tells a disquieting tale. Between 1991 and 1993, the butchered remains of four gay and bisexual men were found along highways in New York, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania. The men had been lured from Manhattan piano bars and chopped into pieces. Most were well-to-do; one, Anthony Edward Marrero, was a blue-collar sex worker. The Last Call Killer, as he came to be known, was meticulous but also sloppy, leaving a trail of clues – a saw, a pair of latex gloves – that led police to focus on the Staten Island area.

More from Rolling Stone

The Scheming Hollywood Superagent Who 'Played God' With Miss America

David Simon, Creator of 'The Wire,' Requests Leniency for Man Charged in Michael K. Williams' Death

Yusef Salaam, Member of the Central Park Five, Wins NYC City Council Primary

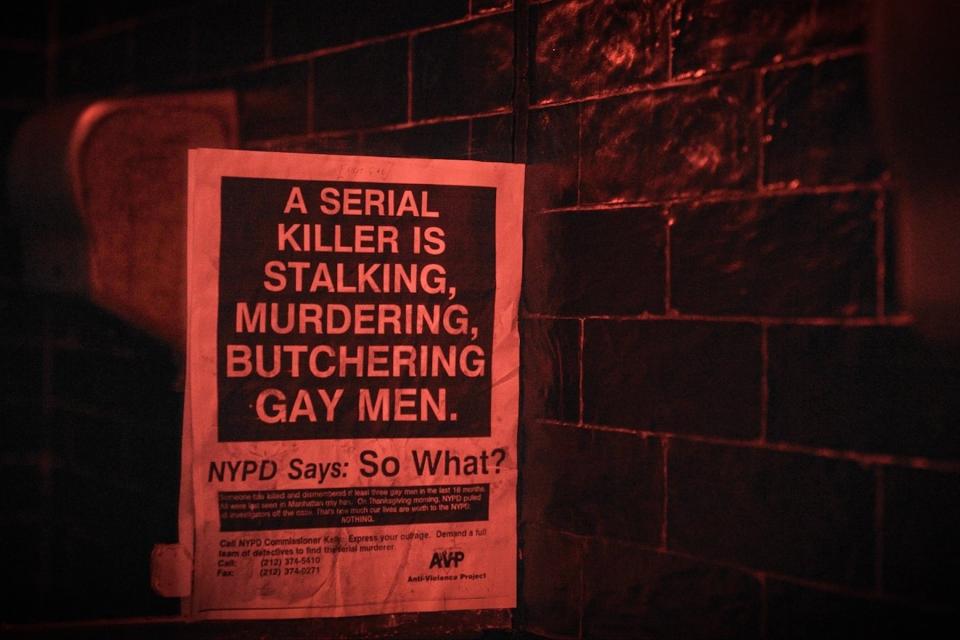

(Warning: spoilers ahead). But Richard Rogers wasn’t arrested until 2001, tracked down through advances in fingerprint technology. It turned out he had also killed a college housemate at the University of Maine, in 1973, but was acquitted on the basis of a so-called “gay panic” defense (he claimed his victim hit on him). Rogers was also arrested after drugging and assaulting a man he met in a bar in 1988, but was acquitted there as well, which allowed to keep killing. Former New York City Anti-Violence Project member Matt Foreman recalls his reaction upon hearing Rogers was finally arrested: “I’m grateful, but what took so long?”

Last Call is about many things, including living in the closet and hunting a killer. It is also a subtle indictment of how gay lives are devalued by society. “When you’re talking about homosexuals, you’re talking about someone who commits a crime,” explains former Patrolmen’s Benevolent Association present Samuel DeMilia in archival news footage. But if the police don’t come out looking good here, the media might look even worse. Take the New York Times obituary brief on Morrero, headlined, “Anthony Morrero: Crack Addict, Prostitute,” which goes on to explain that his life was “marked by a failed marriage, drug addiction and ultimately gay prostitution, the authorities said.” And just like that, a life and death are dismissed. Tabloid headlines described Rogers’ spree with phrases such as “gay-slay.” Clearly, it can’t be easy to solve or report on a crime when you view the victims as less than human.

Caronna creates a steady storytelling rhythm, mixing artful recreations with interviews, period media coverage, maps, and stills; Last Call never feels like it is almost four hours long. The pace is also aided by a vivid and impassioned grasp of the bigger picture. Executive producer Howard Gertler was also a producer of the superb, Oscar-nominated AIDS activism documentary How to Survive a Plague, and Last Call has some of that film’s urgent recounting of the struggle to be seen and heard.

I have but one quibble: a desire to learn more about Rogers. Who is this man? We never really learn, aside from his horrific acts. That’s hardly a deal-breaker; Last Call is ultimately focused on the culture of anti-gay violence, all too common then and on the rise now, and how that culture is perpetuated. In the end, this is more important than the “What makes the serial killer tick?” stories to which we’ve been conditioned. It’s safe to say he hated gay people. Sadly, he had, and still has, plenty of company.

Best of Rolling Stone