‘The Contestant’ Features a Naked Man Losing His Mind on National TV. It’s a Documentary

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

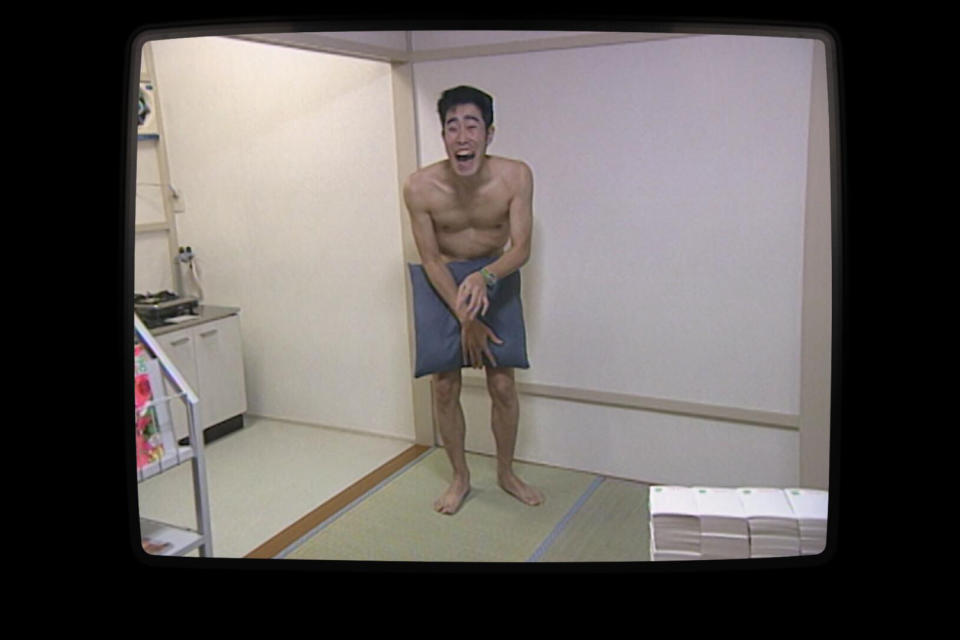

A man walks into a room. He’s just picked a winning ticket in a lottery, been blindfolded, and led through the snow. Now, inside a windowless and mostly bare apartment, he’s being asked to disrobe. I have to take off everything, the man asks? Everything. The fact that a TV producer is telling him this is cause for concern. Besides, isn’t this supposed to be some sort of televised contest? Why is he being left au naturel? Don’t worry, the producer says. Most of this won’t be aired. (This is a lie.)

Naked — unless you count the pillow he’s using cover his crotch — the man checks out his surroundings. There’s a table, a phone, a radio. A pen sits next to several stacks of blank postcards. In the corner, there’s a rack filled with magazines. What’s not there: Food, clothes, amenities of any kind. Now the producer is leaving. If this man wants to survive, he must fill out the postcards and send them in to magazines. He must survive on whatever prizes he wins from sweepstakes. Once he collects the equivalent of $1 million worth of items, he can leave the premise victorious.

More from Rolling Stone

How to Watch 'Thank You, Goodnight: The Bon Jovi Story': Stream the Docuseries Online

Bon Jovi, Forever Young, Comes Face-to-Face With Mortality in 'Thank You, Good Night'

What this man doesn’t know is: He’s being watched. By almost the entire population of Japan, once a week, on TV. A livestream feed will soon broadcast his every move 24 hours a day. Two other things he does not know, not yet: He will barely leave this room or have contact with anyone for the next 15 months. And he’s about to lose his mind.

A chronicle of a media phenomenon, a reality-TV landmark and a psychological nightmare packaged as entertainment, The Contestant is the type of documentary where you’re aware that what you’re witnessing is 100-percent true, and you still can’t quite wrap your brain around what you’re seeing. (It drops on Hulu on May 2nd.) Revisiting a moment in the late 1990s, long before the notion of nonscripted franchises were barely a glint in Mark Burnett’s jaundiced eye, filmmaker Clair Titley’s recounting of how a Japanese show turned an everyday guy into a massive celebrity, one primetime humiliation at a time, offers an extraordinary history lesson on the dawn of 21st century pop culture. We have now been steeped in decades’ worth endless amazing races and survivor challenges and surveilled households and real housewives. But Nasubi got there first.

That’s the nickname of Tomoaki Hamatsu, a young man from Fukushima who dreamed of becoming a comedian. He happens to have a particularly long face, hence “Nasubi,” the Japanese word for eggplant. Like a lot of bullied kids, Hamatsu discovered humor as a defense mechanism; he also adopted the insult as an identity marker, because if you can’t beat them, etc. Leaving for Tokyo to seek his fame and fortune, Nasubi is given one single request from his mother: Just don’t get naked. (Spoiler: This promise will be broken a thousandfold.)

It’s right around this time that a producer named Toshio Tsuchiya is jazzing up Japanese TV with a show called Denpa Shonen — if television is a family, one talking head says, then this series is the resident “naughty boy.” A gonzo affair involving screaming hosts and travelogue vignettes that doubled as endurance tests — how long will it take two dudes to pedal-boat their way to Indonesia, or hitchhike across Africa? — it was part variety show, part gameshow and a prototype for what would, over the next handful of years, become a genre. Critics hated Denpa Shonen. Virtually everyone under the age of 30 loved it.

It was also what one BBC correspondent called “a star machine,” minting its contestants into media darlings practically overnight. So, naturally, Nasubi was among the many hopefuls who went in to audition for some new idea that Tsuchiya wanted to incorporate into the show. It would eventually be called “A Life in Prizes.” And it would indeed make Nasubi extraordinarily famous all across Japan, without him even knowing it.

Titley gets Tsuchiya and Nasubi to sit for long, separate interviews, with each detailing their experience as taskmaster and Truman Show Patient Zero, respectively. As one person notes, however, Peter Weir’s movie featuring Jim Carrey as the unwitting subject of a TV show would not hit theaters until later that same year, after the “Life in Prizes” segments had already begun airing in Japan. The British series Big Brother was still years away. The phrase “reality TV” had not entered the cultural lexicon yet. While this may have not been the absolute first international reality TV show, it was certainly breaking new ground in terms of how far you could take a batshit sociological experiment and turn into appointment viewing. Cruelty was very much the point, per Tsuchiya. It was also one hell of a winning formula.

Yet more than the rearview-mirror testimonies from Denpa Shonen‘s God and Job, it’s the abundance of footage from Nasubi’s attempts to survive on next to nothing for weeks on end that, not surprisingly, make The Contestant both a can’t-look-away car wreck and an indictment of viewer complicity. He’s told that most of the footage will never see the light of day, yet right from the jump, Nasubi begins mugging for the camera. He sings and cracks jokes and, when he wins dog food and begins eating it out of desperation, howls at a moon he can’t see; his weekly dance of celebration becomes a crowd favorite. Since he’s naked, the show’s creators decide to cover his junk with an eggplant emoji, courtesy of his nickname — so you have Tsuchiya and his crew to thank for all of these coded dick texts you get from horndogs as well. He’s got personality to spare, and you can see why audiences take to him.

People also loved watching lions devour Christians back in the day, of course, and no amount of the goofy, over-the-top voiceovers (dubbed into appropriately giddy English here) can mask what soon becomes apparent: Nasubi starts psychologically deteriorating before the eyes of 15 million viewers. They’re tuning in to see what he’ll do next in order to survive on random prizes ranging from a spiny lobster to women’s underwear and a stuffed baby seal. But they’re also watching a man come apart at the seams, and the more feral he gets, the more the ratings keep ascending. Nasubi admits to loneliness, crushing bouts of depression and madness — a montage of him introducing himself as the days tick by in the screen’s corner attests to a growing state of mania. The show almost pulls the plug when he starves to death early on, but they keep pushing, pushing, pushing him to the brink even when he’s unraveling. Because that’s great TV!

It’s what makes a particularly sadistic “reset” within the show so tortuous to witness; you’ll wonder why the Geneva Convention wasn’t invoked at this point. And it’s why, when The Contestant gets to the “finale” of this whole endeavor, that you, too, will feel like you’ve gone through the looking glass. If you know what Tsuchiya has concocted for the big revelation or have seen the footage, then you understand what a mindfuck happening in real time looks like. If not, we’re not going to ruin it for you.

What’s both exciting and horrifying is that, in that exact moment, you feel like you’re seeing the shape of things to come. The documentary catches you up on Nasubi’s life after “A Life in Prizes,” and how he ultimately used his celebrity in the name of good. It’s a happy ending and a hell of a third act. Yet once a specific set of walls come tumbling down, The Contestant suddenly goes full metal Cassandra. This is a peak moment of rock-bottom entertainment, a spectacle of absolute emotional “truth” manufactured for maximum impact. It’s also a glimpse of the new norm, rushing toward us like a runaway train. We’re all contestants now.

Best of Rolling Stone