Connecticut Might Represent the Future of American Criminal Justice. Alabama Is the Hellish Present.

I continue to be intrigued by the place that the issue of criminal-justice reform has in our politics, which is roughly the same as the position held by Ulysses among comp-lit majors-widely admired, but rarely acted upon. It's as though somebody placed the thing in a bell-jar of the finest crystal and put it on a shelf marked "Bipartisan Initiative" so that all the politicians in the country can walk by and admire its beauty on their way to whatever the next fundraiser on the schedule is. I do admire the people on both sides of the big ditch trying to push the same button at the same time.

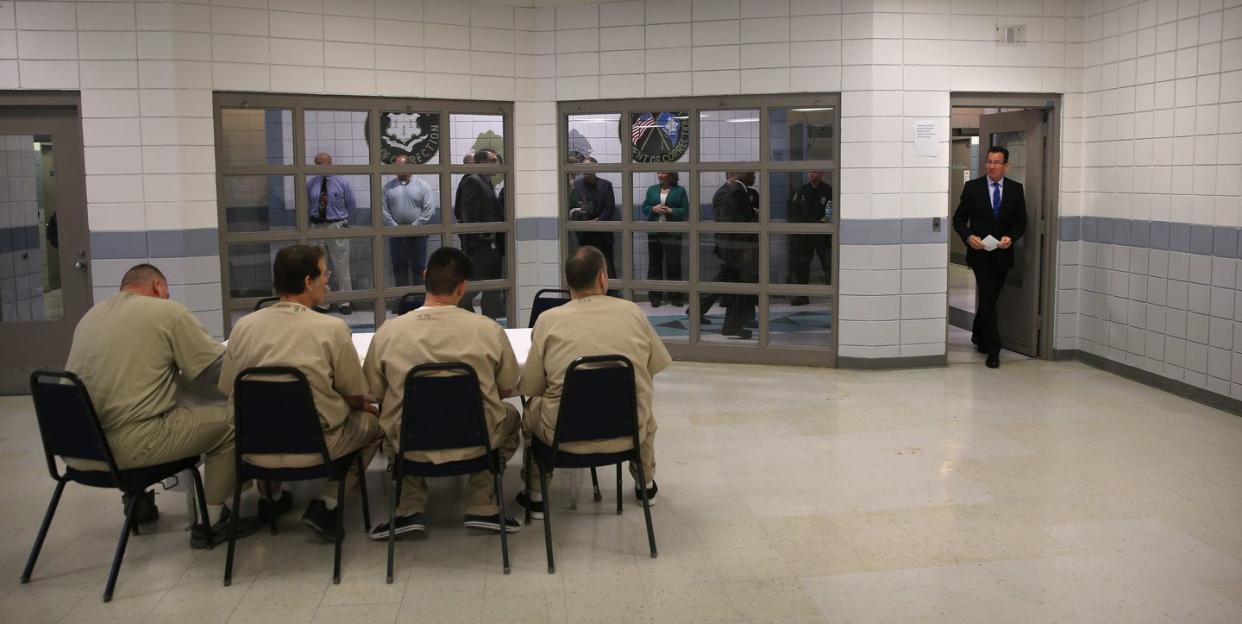

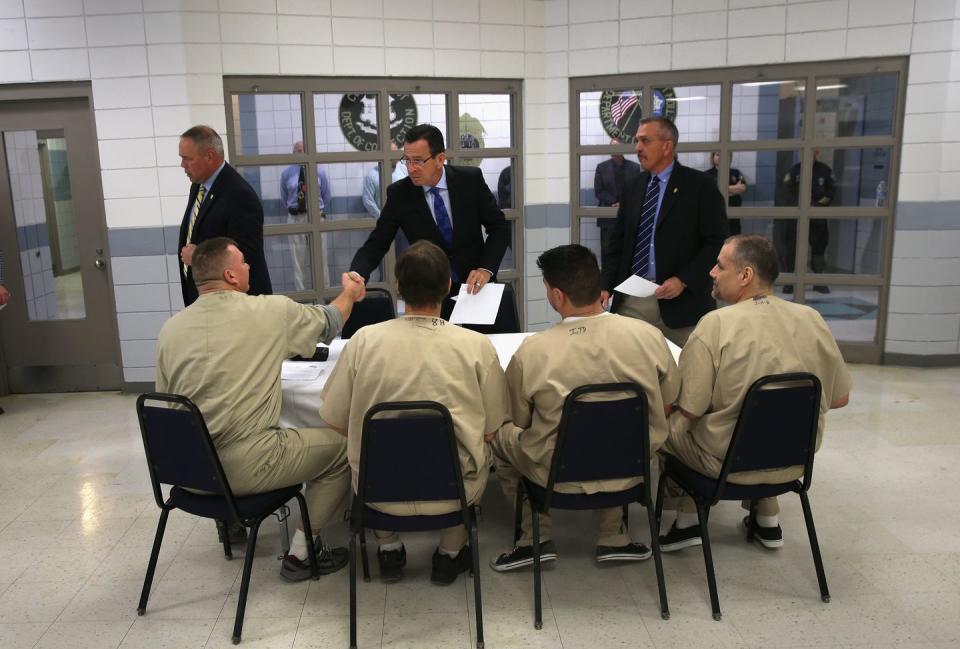

Take this report from 60 Minutes about a prison in Connecticut.

It's a two year old program based on therapy for 18-25 year old prisoners, whose brains, science shows, are still developing, and their behavior more likely to change. The idea came from Germany where the main objective of prison is rehabilitation and where the recidivism rate is about half that of the U.S.

Make America Germany Again.

Warden Scott Erfe and his staff, assisted by the nonprofit Vera Institute of Justice, created a program called T.R.U.E. -- short for truthful, respectful, understanding, and elevating -- that was inspired by Germany's prison system, which focuses on human dignity and rehabilitation. Out of a pool of some 200 applicants, Warden Erfe selected about 50 prisoners between the ages of 18 and 25...Their crimes range from drugs to arson to violent assault. Erfe placed them in a cell block with about 20 respected, older prisoners he tapped to serve as mentors.

One of the mentors is a lifer named Isschar Howard, who is in Cheshire because he killed two people.

"All we knew was we was gonna try and stop these young cats from becoming us. 'Cause you don't want this. If there's one thing I'm an expert in, it's screwing up. I have a PhD in consequences. I can tell you what tear gas tastes like. I can tell you what it feels like to watch your family see you get sentenced to life without parole. And I can tell you the decisions I made to get to that. After that the choice is yours...I don't have to die a waste. I tell these guys all the time they give me purpose to live. They give me something to leave behind."

I hope this works. I hope that the citizens of Connecticut continue to fund experiments like this, and not get scared off if one of the inmates from the program gets out and backslides into crime, causing the voters to backslide into the fearful dynamic that made the program necessary in the first place. Because that road leads to Alabama, and a place called the St. Clair Correctional Facility. From The New York Times:

The prison he found seemed virtually ungoverned. Corrections officers disappeared from cellblocks for long periods. Those who were present were often disregarded. With officers absent or ignored, vulnerable inmates, including those who were wounded and bleeding, often pleaded in vain for help, several inmates said. Violence - robberies in dark tunnels, assaults in crowded dormitories, stabbings in cramped cells - was virtually unavoidable. “Like Devil’s Island,” one current inmate said. Mr. Simon had not been there a month when a man began stabbing him in the face and neck in the middle of the night. He recalled being told afterward by an officer that the man had just been released from the segregation unit: the isolation cells reserved for punishment but increasingly seen as safe havens.

“When we let him out of lockup, he said he was going to stab someone to get back in,” Mr. Simon said he was told. “But they didn’t think he was really going to do it.” Locks have been broken at St. Clair since the 1985 riot and are easily “tricked,” or opened with prison ID cards. Like the other state prisons, St. Clair has been severely overcrowded for many years, as Alabama has long spent less on inmates than almost any other state. Health care across the system has been “grossly inadequate,” a lawsuit by the Southern Poverty Law Center contended. The suit claimed that staff members had given razor blades to suicidal prisoners, and that ill inmates had been placed under “do not resuscitate” orders without their consent.

The place is clearly a hellhole, understaffed and overcrowded. But it's also a laboratory for the forces behind criminal-justice reform and the forces arrayed against it.

But former inmates and officers at St. Clair say the downward spiral began in earnest in 2010, when Mr. Wise, who had become the warden, was moved out. During his tenure, politicians visited and spoke, religious volunteers were constantly on site, inmates taught anti-violence classes, and rewards such as meals from outside were given. “These are human beings you’re dealing with, not potted plants,” Mr. Wise said. Or as one retired St. Clair corrections officer, Jacky Mashburn, put it: “Idle hands is the workshop of the devil.”

Not everyone in the Corrections Department - including the new warden, Carter Davenport - appeared to favor this approach. After he arrived, cutbacks began - of chapel nights, programs, rewards, volunteer visits. The staff steadily began withdrawing from the population, officers and inmates said. Prisoners were left to themselves. “Under Wise, bed changes were granted when problems arose,” one longtime inmate still in St. Clair said, echoing accounts in affidavits. After the warden left, the inmate said, “if you had a problem, it was, ‘Get a knife.’”

The limited capacity of segregation made consistent discipline almost impossible. But that did not mean that punishment stopped altogether. The Equal Justice Initiative lawsuit contains abundant accounts of beatings at the hands of officers on what was described as arbitrary grounds, resulting in stitches and broken bones, and in some cases involving inmates who were shackled. Mr. Davenport, prison officials acknowledge, reported himself for hitting a man who was handcuffed. Mr. Davenport was a “carry-a-big-stick type of guy,” said a former officer who recently quit but did not want to be identified because he was looking for work. “But we didn’t have the numbers in staffing to do that. And that’s when the inmates started figuring out they outnumber the officers.”

And, as always with our politics, there's the money.

He described the recent efforts at improving St. Clair as only a temporary fix, “robbing Peter to pay Paul.” The construction of modern prisons, he said, is the important first step to making changes that will last, allowing for safer facilities and more rehabilitative programming. But the plan, still making its way through the Legislature, has met with deep skepticism, objections that it costs too much, worries from small towns dependent on prisons for jobs and arguments that it does not address the fundamental problems.

I think that the people working on this issue are some of the most genuinely sincere people in our politics. I think that the people who oppose them-like, say, Senator Tom Cotton, the bobble-throated slapdick from Arkansas-are some of the worst. But we are a country that doesn't do big change anymore. If we won't do it for ourselves-witness the resistance and mockery aimed at the efforts to craft an answer to the existential climate crisis-we sure as hell are unlikely to want to make big change in the way we lock up our criminals. But, dammit, somebody has to keep pushing the rock up that hill.

Respond to this post on the Esquire Politics Facebook page here.

('You Might Also Like',)