Congress must consider cuts in Medicare and Social Security. This is why | Peter Crabb

The problem never seems to go away.

No, I am not talking about the coronavirus. Congress is once again debating the constitutional limit on the amount debt the federal government can take on.

Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen sent a stern letter to Congress this month stating that if Congress doesn’t act quickly, she would need to take “extraordinary measures” to prevent the government from defaulting on more than $28 trillion of debt. However, Yellen’s measures, or even a vote by Congress to raise the country’s borrowing limit, are just short-term fixes.

The bigger question no one wants to talk about is how much the government is spending and how it goes about raising taxes. This question has more serious implications for our economic well-being.

Policy makers would do well to heed the economic theory known as Barro-Ricardo equivalence. The theory was first proposed by David Ricardo in the 19th century, and Harvard economist Robert Barro produced a more thorough model of the economy showing the same result.

Barro-Ricardo equivalence states that the timing of government spending has no effect on the economy today. If the government borrows more to spend now with the idea it will pay off the debt with tax revenues later, it is just the same as if the government raised taxes today. The public buys up the new bonds, and in so doing, reduces current consumption just as it would with a new tax.

The implication of this economic model for the current debate is that any increase in the borrowing limit, and the subsequent issuance of new bonds, will affect our economy like a tax. It is hard to think of raising taxes at a time when the economy is finally recovering from the pandemic shutdowns.

The debt issue can be addressed only by changing the federal government’s long-run spending plans. Increasing government debt to fund entitlement programs crowds out capital investment by the private sector today. In the future, it reduces the government’s ability to respond to unexpected challenges like the one we saw last year.

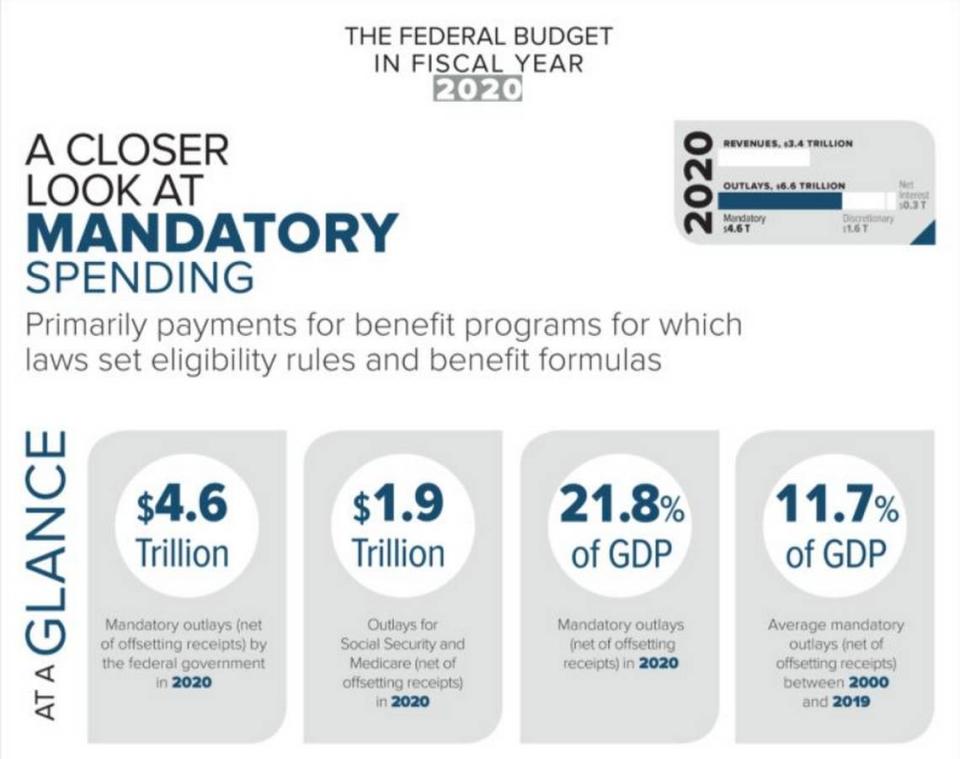

To lower spending, lawmakers will have to consider cutting benefits in Social Security and Medicare, which make up most of the budget. Without reform of these programs, a continued increase in government borrowing will hold back economic growth.

It’s time to end the borrowing debate and address the underlying cause of the problem.

Peter Crabb is a professor of finance and economics at Northwest Nazarene University in Nampa, Idaho. prcrabb@nnu.edu

See what this study just found about Idahoans’ income. You’ll be encouraged | Peter Crabb

Employment is high. But inflation is back, thanks to Federal Reserve | Peter Crabb