How Columbia's Sean Frazier handles magic's blessing, curse in new fantasy novel

The more omnipresent some words are, the less they mean.

If everything is a miracle, perhaps nothing is. And if magic becomes normal, does it still retain that crackle on the tongue when it's invoked? Magic.

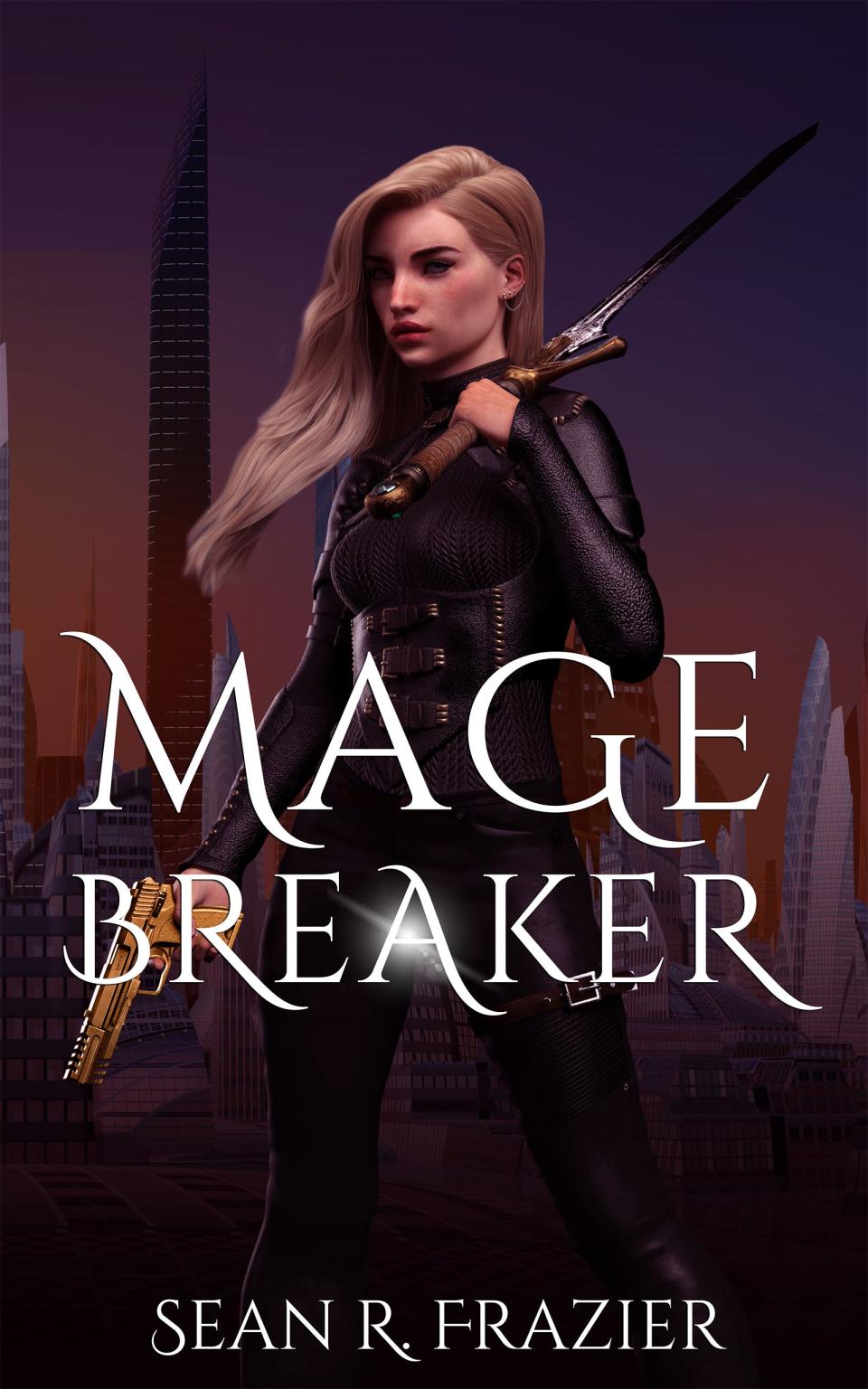

That second question hovers close to the heart of "Mage Breaker," the latest novel from Columbia fantasy writer Sean Frazier. A narrative architect, Frazier builds a brand-new world in which every machine, every system operates on magic.

The concept might sound wondrous at first blush but, as his characters discover, magic's dark and confining side looms, drawing out themes that reach from this fantastical world into ours.

One fantasy follows another

Chronologically, "Mage Breaker" is Frazier's first book since his four-volume "Forgotten Years" series concluded. As with most creative endeavors, the actual timeline was less than linear.

The novel's spark, its "What if?" arrived between the writing of Books Two and Three, Frazier said. Threads of each creative labor wove through the other; he took purposeful breaks from writing his series to chase ideas for "Mage Breaker" and vice-versa.

The process kept both projects fresh and yielded real enjoyment as he sat before the page, he said.

Once the "Forgotten Years" closed, and Frazier was free to fully delve into the world of "Mage Breaker," he felt both absence and excitement. To his surprise, he missed the characters from his first four novels.

"I had spent six years with them — they were almost friends," he said.

But, like the characters he would soon fulfill, Frazier faced a fresh world where "anything's possible," he said.

Magic's blessing and curse

"Magic isn't a gift, it's a prison," a tagline for "Mage Breaker" reads.

At the end of Frazier's pen, the planet Seralune reaches a brave new moment.

"Humanity discovers magic, and all of a sudden things change," he said. "The legacy age was steel and smoke and fossil fuels. But everything runs on magic now."

Shepherded by an alien race called the Kithrak, magic permeates every life and becomes an addictive sort of power; it causes inhabitants to act with a sort of "blind" trust that brokers few questions and backs away from any secrets about how magic really works, Frazier said.

Writing a world that seems to exist without limitations, Frazier embraced his.

"There’s got to be a drawback. I can’t have a utopia without some major conflict," he recalled thinking.

Leaving his characters with total omnipresence would quickly spin scenes and situations into absurdity. Frazier needed to apply some semblance of reality to his magical world, he said.

He created distinct groups, drawing lines between those with unlimited access to magic and those who "get by"; he invented tools that bent magic toward its deeper mysteries; he reframed small but meaningful aspects of the book — like the silence of traffic in a world with magical cars — to show both past and present states.

And perhaps most important, he tried to see each page through the eyes of readers, weighing the concerns they would embrace and the ones he could let go, he said.

Two for the road

Central to the book are two characters as mismatched as any pair within a buddy-cop movie or "odd couple" comedy, Frazier said.

Grouchy gunslinger Ellyne just wants to be left alone, he said. Which proves impossible when she encounters the too-bubbly-for-her-own-good Nicole, who may just expose the Kithrak.

The two become a reluctant sort of "found family," growing toward each other, Frazier said.

"I’m not sure you can relate to either of these characters to begin with, but I think you become more sympathetic to them as they go through their journey," he said.

Beyond this core relationship, other key themes emerge from these pages; their relevance surprises even Frazier. Our often uncritical adoption of technologies like social media and artificial intelligence mirrors social attitudes toward magic here, he said.

And the Kithrak's behavior underlines issues of inclusion, creating a sort of caste system among themselves based on physical features. The "normal"-looking, with only two eyes or two arms, are treated like know-nothings, lesser stakeholders in their world, Frazier said.

Frazier's sentences reflect the growth he felt while writing "Mage Breaker." He very intentionally wed dialogue to action and world-building to plot, so no one sentence is solely exposition- or emotion-driven but lives in a sweeter spot between the two.

The author's next world is already on approach. In early 2024, he will release "The Last Available," a book he said resembles the "most dysfunctional adventuring party" you can imagine in a Dungeons & Dragons game or other role-playing realm.

The truly "last available" people to save the planet take on the mission and, in doing so, steer into every possible trope, Frazier said. The book is a work of pure humor, centering some of the worst people he's ever written, in a way that will inspire laughs, he said.

As the author is finding, creative magic takes on many forms and not only recognizes our limitations but flourishes within them.

Frazier will celebrate the launch of "Mage Breaker" at 6:30 p.m. Nov. 29 at Skylark Bookshop. Find more details at https://www.skylarkbookshop.com/new-events.

Aarik Danielsen is the features and culture editor for the Tribune. Contact him at adanielsen@columbiatribune.com or by calling 573-815-1731. He's on Twitter/X @aarikdanielsen.

This article originally appeared on Columbia Daily Tribune: Columbia fantasy author's latest explores blessing, curse of magical world