Coach Almost Died in Burundi Genocide — Now He Spreads Hope: 'Vengeance Isn't the Solution'

If you talk to members of Gilbert Tuhabonye's running club in Austin, Texas, they'll tell you about his broad smile or easy laughter, or the way he can turn a 5:30 a.m. training session into a dance party.

"If you say the name Gilbert in Austin, 'joy' is going to be in the first three words of describing him. He just wants to spread joy," says his friend Elissa Jackson, a former member of his club. "You would never, ever know what he's been through."

That painful history, however, is written in the scars that mark Tuhabonye's right arm and leg and snake across his back. Faded but still conspicuous, they tell a story of a horror that could have destroyed him, but instead became his inspiration to live with love.

As a high school student and cross-country champion in the East African nation of Burundi in 1993, Tuhabonye saw the worst of humanity when his Hutu teammates turned against him and other members of the minority Tutsi tribe in a murderous rage following the execution of the country's Hutu president by Tutsi extremists. The violence left scores of his classmates dead and him with injuries so severe doctors said he'd never run again.

But 28 years later, as the coach of Gilbert's Gazelles, one of the largest running groups in Austin, and the founder of the Gazelle Foundation, a charity that brings clean water to more than 115,000 people in Burundi — Tutsis and Hutus alike — Tuhabonye, now 46, has embraced hope and forgiveness over anger and vengeance.

"I believe God gave me another chance to live," Tuhabonye tells PEOPLE in this week's issue. "That's why I'm dedicated to making a difference and preaching peace."

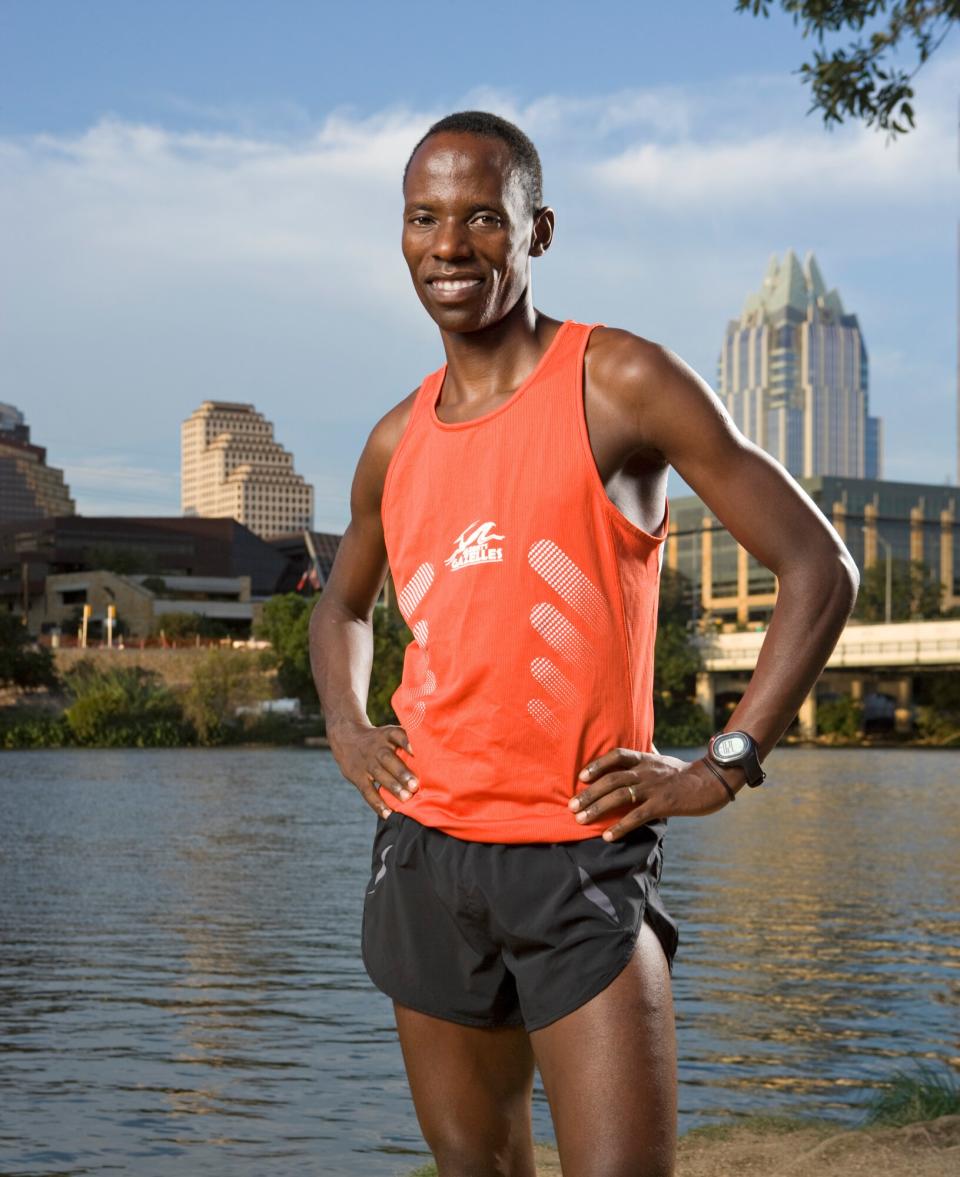

Holly Reed Photography Gilbert Tuhabonye

Growing up in rural Burundi, running was a way of life. Raised on a farm in the mountainous country, where his parents grew corn, peas and sorghum, Tuhabonye would run miles in the mornings to fetch water before running six more miles to school. He'd run to the market and he'd run in the fields, herding cows.

"Whenever my mom or grandma needed anything they'd rely on me," he says. "I'd say, 'I can go!' I was fast and I loved it."

In the seventh grade, he left home for boarding school seven hours away and discovered his speed was good for more than chores. By his senior year in 1993, he was a standout on the track team and had dreams of earning a scholarship from an American university. But Burundi was crumbling around him. Long-standing tribal tensions between the country's two main tribes exploded after the assassination of Burundi's Hutu president by Tutsi extremists on Oct. 21, 1993. Tuhabonye and other members of the Tutsi tribe became targets.

Holly Reed Photography Gilbert’s Gazelles runners training with Gilbert Tuhabonye.

RELATED: Holocaust Survivor Reunites with the Family That Helped Hide Her from the Nazis After 73 Years

Word spread at school that Tuhabonye, along with other Tutsi students and faculty, was to be killed — and that even his Hutu headmaster and track teammates had betrayed him. He attempted to flee with a group of 300 Tutsis, but they were captured. Those not killed by machetes wielded by the mob were bound together with rope, stripped of their clothes and forced into a nearby gas station. The Hutus set the room on fire.

"I witnessed my friends dying one by one," recalls Tuhabonye, who recounts the massacre in his 2006 autobiography This Voice in My Heart. "And I was waiting for my turn."

For eight hours, Tuhabonye braced himself against the bodies, protecting himself from the heat as best he could. In the midst of the horror, he remembers hearing a voice in his head that calmed him: "Son, nothing will happen to you."

Severely burned, Tuhabonye managed to climb out a window and make it to a hospital. Doctors told him he might never run again.

"I thought my life was gone," he says.

For more on Gilbert Tuhabonye's incredible journey, pick up the latest issue of PEOPLE, on newsstands Friday, or subscribe here.

After three months in recovery, "trying to understand how people that were your friends can be so evil," he says, "I needed to find a way to move on."

He turned to the Bible — and thought of the voice he'd heard in the building.

"I realized vengeance isn't the solution," he says. "It's a cycle that never ends. I chose to forgive."

By 1995, he was competing again, and in 1998, he earned a scholarship to run at Abilene Christian University in Texas.

"People were drawn to him," says his Abilene coach, Jon Murray. "You feel like you can be a better person just talking to him."

Courtesy Gilbert Tuhabonye In 2010 Gilbert Tuhabonye (with his wife, Triphine, and daughters Grace and Emma at his naturalization ceremony) became an American citizen.

After graduating and marrying his wife, Triphine (the couple have two daughters, Emma, 20, and Grace, 15), Tuhabonye moved to Austin to work in a running shop. By 2002, he'd formed Gilbert's Gazelles. Among his runners was a college student who also happened to be the daughter of the president.

"I was immediately struck by his positivity," says Jenna Bush Hager, who ran with the Gazelles her senior year at the University of Texas in 2004.

Tuhabonye, who had no idea who she was at the time, made a lasting impression.

"You'd think he should be bitter and angry," she says. "But he channeled that through running and teaching. To me, he embodied pure love and grace."

RELATED: High School Wrestling Coach Gives Student Athlete a Home and Future: 'He Became Like a Son to Me'

For Tuhabonye, who's also head track coach at St. Andrew's Episcopal School in Austin, that's proof that sharing his painful story is worthwhile.

"I want people to know that we live in a world where bad things happen," he says. "But you figure out a way to move on."

Spencer Selvidge Since Tuhabonye cofounded the Gazelle Foundation in 2006, the group has built 60 water systems, bringing clean water to more than 115,000 people in Burundi.

One way he does that is by looking beyond tribal divisions to bring clean water to all of Burundi, where one of five deaths is caused by water-borne illness.

"Part of the healing is bringing the community — Hutus and Tutsis — together to share water," says Tuhabonye. "My hope is they think about sharing and not killing each other."

Tuhabonye has moved on from the nightmare that scarred him 28 years ago, but he's never forgotten it. Each year on Oct. 21, the anniversary of the massacre, Tuhabonye marks the day not by mourning, but with a celebration of life. He wakes with a prayer and then makes a pilgrimage with a group of friends, each carrying a 20-pound jug of water on their heads, up a hill to Austin's capitol to raise awareness of the need for clean water in Burundi.

"I almost died that day and I lost friends and classmates. On that day each year, I think about how lucky and blessed I am to be alive," he says. "It puts me in a happy place knowing that we're helping people."